The meeting in 1811, of Tecumseh, the mighty Shawnee, with Apushamatahah, the intrepid Choctaw.

I will here give a true narrative of an incident in the life of the great and noble Choctaw chief, Apushamatahah, as related by Colonel John Pitchlynn, a white man of sterling integrity, and who acted for many years as interpreter to the Choctaws for the United States Government, and who was an eye-witness to the thrilling scene, a similar one, never before nor afterwards befell the lot of a white man to witness, except that of Sam Dale, the great scout of General Andrew Jackson, who witnessed a similar one that of Tecumseh in council assembled with the Muskogee’s, shortly afterwards of which I will speak in the history of that once powerful and war-like race of people.

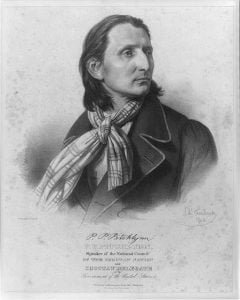

Colonel John Pitchlynn was adopted in early manhood by the Choctaws, and marrying among them, he at once became as one of their people; and was named by them “Chahtah It-ti-ka-na,” The Choctaws Friend; and long and well he proved himself worthy the title Conferred upon, and the trust confided in him. He had five sons by his Choctaw wife, Peter, Silas, Thomas, Jack and James, all of who prove to be men of talent, and exerted a moral influence among their people, except Jack, who was ruined by the white man s whiskey and his demoralizing examples and influences. I was personally acquainted with Peter. Silas and Jack, the former held, during a long and useful life, the highest positions in the political history of his Nation, well deserving the title given him by the whites, “The Calhoun of the Choctaws;” but of whom I will speak more particularly else where.

England, in her anticipated war with the United States in 1812, early made strenuous efforts to secure the co-operation of all the Indian tribes, both north and south, as allies against the Americans, as she had done against the French previous to supplanting them in 1763; though, not with that success that she did in arraying them in opposition to the Americans; for to the honor and praise of the majority of the early settlers of the French among the North American Indians be it said, that they had won the respect, confidence and love of the northern Indians especially, by their freedom from all arrogance, abuse and oppression, and by honest dealing with them, comparing well in this particular with the Quakers, and thus seeming to the, highly appreciative Indians more as affable companions and genial friends, than insolent and pretended masters, as the English had assumed to be, and afterwards the Americans, who followed in their wake; both of whom, early and late, introduced the traffic in whiskey among them, which had been effectually prohibited by the French down to that time.

Having secured the co-operation, however, of many of the northern tribes to operate under the command of the cruel Proctor, the English then turned their attention to the securing of the southern tribes as allies, especially the five great and most war-like tribes then within the boundaries of the United States, viz: The Choctaws, Chickasaws, Cherokees, Muskogee’s and Seminoles, whose warriors were then justly considered as the shrewdest, bravest and most to be dreaded in war of all the North American Indians; and that they might the more effectually and with greater certainty secure the aid of those brave, skillful and daring warriors of the south, the renowned Shawnee chief, Tecumseh, was sent to persuade them by his great influence and unsurpassed native eloquence to unite with them as allies in the expected war. As one of the bravest and most skillful Indian chiefs that ever trod the American soil; as a statesman in the council of his nation; as a foresighted politician; as a man of integrity and humanity, according to the morals of his people; as a man of comprehensive mind, rich in resources for every emergency; as a man of undaunted nature, Tecumseh stands with no superiors and few equals upon the pages of Indian history; and his name still hovers among the northern and western tribes, with those of Sassacus, chief of the Pequods, in 1637; Philip, chief of the Pokanokets in 1674; Canonochet, chief of the Naragansetts in 1675; and the great Pontiac, chief of the Ottawas in 1763; Red Jacket, of the Senecas; Black Hawk, of the Sacs and Fox, and others, who figured along down the path of time in their noble but vain endeavors to protect their homes and country from the encroachment of foreign vandals, as the heroes, who, in the days of their prosperity and strength, had each devised the plan for unity of action among all the tribes in driving back the usurping whites from their common territories, and conducted their mighty but unavailing struggles with seeming destiny for the continued independence of their race, as men who loved no enjoyment equal to that of perfect personal freedom in the companionship of nature, as it then presented itself in its picturesque garb of mountains and valleys, rivers and lakes, forests and prairies, affording them all the necessaries of life, and uniting to consummate their earthly bliss as a free, independent, contented and happy people. Therefore one master spirit filled and ruled the hearts of those ancient chieftains, and gave to their whole lives their character.

Willingly, therefore, did Tecumseh accept the embassy to the southern tribes, in behalf of the English; nor could they have confided their mission with greater hope of success to a more influential chief, or a bitterer enemy to the Americans than to Tecumseh? North and South, far and near, was the name of the great Shawnee Chief, and warrior known. From their youth the warriors of all the: tribes, at that day and time, had heard of his great achievements in battle; of his irresistible eloquence in debate and the devastation that marked his footsteps upon the war-path; for his tomahawk was like the lightning bolt in force and power, armed with swift and sure destruction to all upon whom it fell when wielded by its master’s hand, to all Indians, a meritorious commendation and worthy all acceptation. Unknown to fear, yet it is said of Tecumseh that his heart was tender as a child’s, and the sufferings of a friend whom he loved could torture him with the keenest anguish. His mother was a Muskogee and his father a Shawnee; and both were born in Alabama, at a village called Sau-van-o-gee (afterwards known as “Old Augusta”) on the Tallapoosa River, though Tecumseh’s father and grand parents belonged to the Shawnees of the North. They moved to the then wilds of the now State of Ohio with their family of several children, where, in 1768, Tecumseh was born, who became so distinguished in the history of his race as a chief and warrior. He had five brothers, all of whom were noted warriors. He also had one sister named Tecum-a-pease, who was highly endowed as a woman of strong character and sound judgment, and a great favorite of her war-like brother, over whom she exercised great influence. At the age of nineteen years Tecumseh visited the South, once the home of his parents, where he spent a few years principally among the Muskogee’s, the relatives and friends of his mother engaging with them in their hunts and various amusements, and winning their admiration by a heroism free from temerity, and a friendship free from partiality.

In the spring of 1811, Tecumseh, with thirty congenial spirits all well mounted, again left his northern home and directed his course once more to the South to visit those distant friends, not as before, a pleasure seeker in their hunts, national festivals and social amusements, but as one seeking co-operative vengeance upon a common foe, the pale-face intruders and oppressors of their race. Silently and fearlessly did the little band of resolute men, keep their course with un wearied resolution and unerring judgment through the vast wilderness that intervened; over hills and endless wastes; swimming broad rivers and narrow creeks, and working their way through wide extended cane brakes, where seldom or never before had trod human feet, the sun their guide by day, the stars, by night, until they reached the broad territories of the Chickasaws through which they passed, nor ceased their march, until they entered the Choctaw Nation in the district over which Apakfohlichihubih was the ruling chief and there pitched their camp. Soon the tidings of the arrival and encampment of the renowned Shawnee chief and his thirty warriors as an embassy were borne as on wings of the wind, throughout the district fanning the hitherto quiet inhabitants into a blaze of the wildest excitement, and many rushed at once to see the great Chieftain and his warriors; actuated more however through curiosity than expectation of learning anything concerning the intent or purpose of their coming; for an Indian ambassador is ever silent upon the subject of his mission, and opens not his mouth but in council assembled, and thus manifesting good sense and profound judgment. In solemn pomp, therefore, Tecumseh and his warriors were escorted to the home of Apakfolichihubih, to whom Tecumseh stated that his business was of a national character and of the most vital importance, to the Choctaw Nation. At once Apakfolichihubih, summoned the warriors of his district to convene in council, at which a resolution was passed calling the entire Choctaw Nation to assemble in a great council, extending the invitation alike to the Chickasaw Nation, stating as a reason, that it was made through the request of Tecumseh, as an ambassador of the Shawnees; that he, with thirty warriors, was now a guest of Apakfolihchihubih, and had a proposition to lay before the council of vital import to both Nations. A day was also appointed and the place designated, in and at which the two Nations should assemble in united council to hear the words of the mighty Shawnee. The place selected at which the council was to convene, was at a point on the Tombigbee River miles (by land) north of Columbus, Mississippi, and now known by the name of Plymouth.

Immediately runners (news horsemen) were sent out to the remotest points of their country, also to the Chickasaws, to notify all of the coming” event; and soon they were seen on their fleetest horses speeding in wild haste and in all directions, over their wide extended territory; even as was witnessed when our Declaration of Independence was first pro claimed, and the “Old Liberty Bell” rang out its joyous peals echoing amid wild shouts along the hills of the Atlantic shore, but to die away in muffled tones among the rocky battlements of the far-away Pacific coast; and as the tones of the “Old Liberty Bell” secured responsive ears, so too the call of Tecumseh secured the speedy response of every Choctaw and Chickasaw warrior, however remote his cabin from the designated place of rendezvous.

For many days previous to the convening of the council, hundreds upon hundreds of warriors, in various groups, were seen slowly and silently wending their way through the forests from every direction toward the designated place for the meeting of the two Nations in council with the mighty chief and Shawnee ambassador; and when the appointed day came, many thousands had presented themselves.

Col. John Pitchlynn stated to the missionaries who established a mission among the Choctaws several years after, that he never saw so great a number of Indian warriors gathered together. It was indeed a congregation vast of solicitous and expectant men, whose breasts heaved and tossed with the conflicting emotions of the wildest imaginations, for rumor of war between the United States and England had reached them in their distant villages situated along the banks of their rivers and creeks, and in their humble cabins found scattered everywhere amid the deep solitudes of their seemingly illimitable forests; therefore hope and fear alternately held dubious sway over their minds as to the design of Tecumseh’s unexpected visit, and the calling them together in council, which seemingly foreshadowed evil, also to their respective nations as compulsory allies to the one or to the other of the belligerent parties; still no external manifestations of any kind whatever were seen that betrayed the secret emotions within, as profound silence and the utmost decorum were always and everywhere observed by the North American Indians when assembling and having assembled in national council.

But the light of that memorable day seemed to wane slowly, and its sunset was followed by that seemingly breath less pause and stupor so oft experienced in a southern clime. The increasing dusk crept by degrees, while the outlines of familiar objects became blurred, then dim and fantastic in the uncertain light. At length the leaves began to stir and the placid waters of the itombi ikbi trembled in the darkness, for the night wind had sprung .up freighted with the cool breath and sweet odors of the surrounding forests, as twilight dropped her mantle to her successor night. Then a huge pile of logs and chunks, previously prepared, was set on fire the signal to the waiting multitudes, which sat in groups of hundreds around chatting in low tones and smoking their indispensable pipes, constructed in the heads of their tomahawks. Each group arose without delay or confusion and in obedience to its mandates, marched up in solemn and impressive silence, and took their respective seats upon the ground forming” many wide, extended circles around the blazing heap, but leaving an open space of twenty or thirty feet in diameter for the occupancy of the speaker and his attendants.

The chiefs and old warriors always formed the inner circle; the middle aged, next, and soon to the outer circle, which was composed of the young and less experienced warriors, thus carrying out the old precept, “The old for counsel, the young for war.” All being seated, the pipes, indispensable adjuncts in all the North American Indians national and religions assemblies, were lighted, and commenced their rounds through the vast concourse of seated men; and each one, as a pipe came to him, drew a whiff or two, and then, in turn, passed it on to the next, while pro found silence throughout the vast assembly reigned supreme, disturbed alone by the crackling and sputtering of the burning logs. Twas indeed a silence deep, as if all nature had made a pause prophetic of the gathering storm.

Indian Councils

What a beautiful characteristic of the North American Indians was that of repressing every emotional feeling when assembled in council or otherwise, and observing the most profound silence when one of their number was speaking! Even in the social circle, never but one speaks at a time while the closest attention is given and the most profound silence observed by the others. This was and is a part of their education, an established rule of their entire race, into the violation of which they were seldom if ever betrayed by any kind of excitement whatsoever; and in visiting the Choctaw and Chickasaw councils in 1885, I found they still adhered to the old established rule with the same rigid tenacity as did their ancestors east of the Mississippi River in the days of the long ago. For this noble virtue (for virtue it may be called) they are termed taciturn and grave, yet their national sensibilities are deep, active and strong.

Soon Tecumseh was dimly seen emerging from the darkness beyond into the far reflected light of the blazing logs, followed by his thirty warriors. With measured steps and grave demeanor they slowly advanced. But no wild shouts heralded their coming. No deafening yells proclaimed their welcome. Silence deep and profound swayed her sceptre there. Yet that vast assembly of silent men seated in circles upon the ground, while clouds of tobacco smoke gently floated over their heads; with countenances beaming with inquiry as their calm but piercing eyes glistened in the reflected light of the blazing logs, spoke a language to Tecumseh more potent than the wild huzzas of the whites ever did to their approaching political favorite. In silence the circle was opened as Tecumseh and his followers drew near through which they slowly marched, then immediately closed behind them surrounding them by thousands of strangers; but nothing to fear, for the Peace Pipe was in the left hand of the mighty Shawnee, an emblem rigidly respected by all North American Indians all over the continent. When Tecumseh had reached a point near the fire, he halted and his thirty warriors at once seated themselves on the ground forming a crescent before their adored chieftain, while he, the personification of true dignity and manly beauty, stood erect and momentarily flashed his piercing eyes over the mighty host as if to scan each countenance (that index of the soul) and read its import, the better thereby to lay a proper basis for the successful effect of his arguments in the sup port of his mighty scheme.

Every eye was now fastened upon him, while, in turn, beneath his high forehead flashed his own black and restless eyes; and though his face wore a calm expression yet there was a nervousness about him with all that plainly indicated one of those sensitive organisms that kindle at the slightest warmth. But he sought not the personal admiration or the praise of his audience. He meant business serious and weighty; business, in which he fell, was involved the future destiny of the entire Indian race for weal or woe. Noble and unselfish patriot! How true thy farsighted statesmanship! But alas, how unavailing! What an imposing and impressive scene was there! A hundred closely formed circles of silent men seated on the ground from whose dark features were reflected, by the light on the burning log-heaps, a thousand conflicting emotions of hope and doubt, as they gazed in profound silence upon the imposing figure that stood in their midst. The scene at this juncture, stated Col. Pitchlynn, was grand and imposing indeed, and worthy the pencil of a Raphael. Every countenance told of suppressed feeling, and every eye sparkled with mental excitement. An enthusiasm bordering on ecstasy marked the manner of the elder, while the young, sturdy fellows in the flower of manhood s strength, had more than usual expression upon their faces, which indicated that some of the deepest chords in their natures had already been struck, holding out a promise to them of things undreamed of before, by touching that note to which their every breast gave more or less response.

Tecumseh’s observant eye read its import at a glance, and at once the tones of his voice broke the stillness. Now he seemed nothing but nerves, and shot out magnetism that electrified his hearers into like intensity of feeling, and every nerve and muscle of the vast assembly seemed to take up the measure and tingle with the same enthusiasm and feeling, as the wild orator voiced the sentiments of his audience. In the outset he unfolded the designs of the whites and their schemes to accomplish them; he portrayed the consequences that would inevitably ensue in case they should get the ascendancy; he spared no artifice, omitted no topic that would have a tendency to alarm their concern for their country, or their fears for themselves; he arraigned all the conduct of the whites since their first introduction among their race, and portrayed in vivid colors their ingenuity in concealing” their avarice and covetousness under a veil of most generous and disinterested principles; and how insidious and vile their schemes had ever been, and still continued to be; he made good use of the figures which gave force and energy to his discourse, for no one better understood the designs of the white man, and no one could better explain them than he; therefore he drew his lines, sketched his plans, and well did the drawings and sketches manifest the master’s hand; and ere he had closed, strange alternatives of elevating hope were manifest in the countenances of his silent and attentive hearers.

He began his speech in a grave and solemn manner, stated Col. Pitchlynn, which I here give in substance, as follows:

“In view of questions of vast importance, have we met together in solemn council tonight. Nor should we here debate whether we have been wronged and injured, but by what measures we should avenge ourselves; for our merciless oppressors, having long since planned out their proceedings, are not about to make, but have and are still making attacks upon those of our race who have as yet come to no resolution. Nor are we ignorant by what steps, and by what gradual advances, the whites break in upon our neighbors. Imagining themselves to be still undiscovered, they show themselves the less audacious because you are insensible. The whites are already nearly a match for us all united, and too strong for any one tribe alone to resist; so that unless we support one another with our collective and united forces; unless every tribe unanimously combines to give a check to the ambition and avarice of the whites, they will soon conquer us apart and disunited, and we will be driven away from our native country and scattered as autumnal leaves before the wind.

“But have we not courage enough remaining to defend our country and maintain our ancient independence? Will we calmly suffer the white intruders and tyrants to enslave us? Shall it be said of our race that we knew not how to extricate ourselves from the three most to be dreaded calamities folly, inactivity and cowardice? But what need is there to speak of the past? It speaks for itself and asks, where today is the Pequod? Where the Narragansetts, the Mohawks, Pocanokets, and many other once powerful tribes of our race? They have vanished before the avarice and oppression of the white men, as snow before a summer” sun. In the vain hope of alone defending their ancient possessions, they have fallen in the wars with the white men. Look abroad over their once beautiful country, and what see you now? Naught but the ravages of the pale-face destroyers meet your eyes. So it will be with you Choctaws and Chickasaws! Soon your mighty forest trees, under the shade of whose wide spreading branches you have played in infancy, sported in boyhood, and now rest your wearied limbs after the fatigue of the chase, will be cut down to fence in the land which the white intruders dare to call their own. Soon their broad roads will pass over the grave of your fathers, and the place of their rest will be blotted out forever. The annihilation of our race is at hand unless we unite in one common cause against the common foe. Think not, brave Choctaws and Chickasaws, that you can remain passive and indifferent to the common danger, and thus escape the common fate. Your people too, will soon be as falling leaves and scattering clouds before their blighting breath. You too will be driven away from your native land and ancient do mains as leaves are driven before the wintry storms.”

These were corroding words; and well might terrible thoughts of resistance pass through the minds of those freemen and patriots, as, by the light of the burning heap gleaming through the darkness of the night, they in admiring silence gazed upon the face of Tecumseh and listened to his untaught eloquence, which thrilled and swayed, their hearts and moved the deep waters of their souls, as he plead the cause of right from the vindications of his own heart upon which was written the statute “A favor for a favor, an injury for an injury.”

“Sleep not longer, O Choctaws and Chickasaws,” continued the indefatigable orator, “in false security and delusive hopes. Our broad domains are fast escaping from our grasp. Every year our white intruders become more greedy, exacting, oppressive and overbearing. Every year contentions spring up between them and our people and when blood is shed we have to make atonement whether right or wrong, at the cost of the lives of our greatest chiefs, and the yielding up of large tracts of our lands. Before the pale faces came among us, we enjoyed the happiness of unbounded freedom, and were acquainted with neither riches, wants, nor oppression.” How is it now? Wants and oppressions are our lot; for are we not controlled in everything, and dare we move without asking, by your leave? Are we not being stripped day by day of the little that remains of our ancient liberty? Do they not even now kick and strike us as they do their blackfaces? How long will it be before they will tie us to a post and whip us, and make us work for them in their cornfields as they do them? Shall we wait for that moment or shall we die fighting before submitting to such ignominy”?

At this juncture a low, muffled groan of indignation forced its way through the clinched teeth running through the entire assembly, and some of the younger warriors, no longer enabled to restrain themselves, leaped from their seats upon the ground, and, accompanying the act with the thrilling war-whoops of defiance, nourished their tomahawks in a frenzy of rage. Tecumseh turned his eyes upon them with a calm but rebuking look, which spoke but too well his disapproval of such an undignified and premature display of feelings, which had interrupted him; then with a gentle wave of the hand, the interpretation of which was not very difficult, he again continued: “Have we not for years had before our eyes a sample of their designs, and are they not sufficient harbingers of their future determinations? Will we not soon be driven from our respective countries and the graves of our ancestors? Will not the bones of our dead be plowed up, and their graves be turned into fields? Shall we calmly wait until they become so numerous that we will no longer be able to resist oppression? Will we wait to be destroyed in our turn, without making an effort worthy our race? Shall we give up our homes, our country, bequeathed to us by the Great Spirit, the graves of our dead, and everything” that is dear and sacred to us, with out a struggle? I know you will cry with me, Never! Never! Then let us by unity of action destroy them all, which we now can do, or drive them back whence they came. War or extermination is now our only choice. Which do you choose? I know your answer. Therefore, I now call on you, brave Choctaws and Chickasaws, to assist in the just cause of liberating our race from the grasp of our faithless invaders and heartless oppressors. The white usurpation in our common country must be stopped, or we, its rightful owners, be forever destroyed and wiped out as a race of people. I am now at the head of many warriors backed by the strong arm of English soldiers. Choctaws and Chickasaws, you have too long borne with grievous usurpation inflicted by the arrogant Americans. Be no longer their dupes. If there be one here tonight who believes that his rights will not sooner or later, be taken from him by the avaricious American pale-faces, his ignorance ought too excite pity, for he knows little of the character of our common foe. And if there be one among you mad enough to undervalue the growing power of the white race among us, let him tremble in considering the fearful woes he will bring down upon our entire race, if by his criminal indifference he assists the designs of our common enemy against our common country. Then listen to the voice of duty, of honor, of nature and of your endangered country. Let us form one body, one heart, and defend to the last warrior our country, our homes, our liberty, and the graves of our fathers.

“Choctaws and Chickasaws, you are among the few of our race who sit indolently at ease. You have indeed enjoyed the reputation of being brave, but will you be indebted for it more from report than fact? Will you let the whites encroach upon your domains even to your very door? Before you will assert your rights in resistance? Let no one in this council imagine that I speak more from malice against the pale-face Americans than just grounds of complaint. Complaint is just toward friends who have failed in their duct; accusation is against enemies guilty of injustice. And surely, if any people ever had, we have good and just reasons to believe we have ample grounds to accuse the Americans of injustice; especially when such great acts of injustice have been committed by them upon our race, of which they seem to have no manner of regard, or even to reflect; They are a people fond of innovations, quick to contrive and quick to put their schemes into effectual execution, no matter how great the wrong and injury to us; while we are content to preserve what we already have. Their designs are to enlarge their possessions by taking yours in turn; and will you, can you longer dally, O Choctaws and Chickasaws? Do you imagine that that people will not continue longest in the enjoyment of peace who timely prepare to vindicate themselves, and manifest a determined resolution to do themselves right whenever they are wronged? Far otherwise. Then haste to the relief of our common cause, as by consanguinity of blood you are bound; lest the day be not far distant when you will be left single-handed and alone to the cruel mercy of our most inveterate foe.”

Though the North American Indians never expressed their emotions by any audible signs whatever, yet the frowning brows, and the flashing eyes of that mighty concourse of seated and silent men told Tecumseh, as he closed and took his seat upon the ground among his warriors, that he had touched a thousand chords whose vibrations responded in tones that were in perfect unison and harmony with his own, and he fully believed, and correctly too, that he had accomplished the mission where unto, he was sent, even beyond his most sanguine hopes and expectations.

A few of the Choctaw and Chickasaw chiefs now arose in succession and, walking to the center, occupied, in turn, the place which Tecumseh had just vacated and expressed their opinions upon the question so new and unexpectedly presented to them for their consideration; the majority leaning to the views advanced by the Shawnee chief, a few doubting their expediency. Tecumseh was now jubilant, for his cause; seemed triumphant. But at this crisis of affairs, a sudden and unexpected change came over the scene. Another, who, up to this time, had remained a silent but attentive listener, arose and, free of all restraint, marched to the center mid the deep silence that again prevailed. A noble specimen also, was he, of manly beauty, strength, [and unlettered eloquence, who was to fasten a ring in the nose of the mighty Shawnee to lead him before all the Philistines at his royal will and pleasure. As he drew himself up to his full height, there was revealed the symmetrical form of the intrepid and the most renowned and influential chief of the Choctaws, a man of great dignity, unyielding firmness, undisputed bravery, undoubted veracity, sound judgment, and the firm and undeviating friend of the American people. He was Apushamatahah.

All eyes were at once turned to and riveted upon him, as he momentarily stood in profound silence surveying the faces of his people with that indescribable expression which indicated to the stranger, and none the less to the astonished gaze of Tecumseh, that under it lurked such fearlessness as commanded respect. How truly and plainly the soul writes its tale on that expressive and plastic tablet the face of man! Though habitually of a lively and jovial disposition, yet Apushamatahah could rival the lynx when he applied his penetrating mind to detect the weak points of his opponent, and present his arguments in such a manner as to unravel the hidden meaning of those of his antagonist. Free from any nervous agitation he calmly looked over his audience. His long black locks fell back from a broad manly brow, from which shone dark, eloquent eyes full of depth and lire; his face broad and of a clear olive tint, his lips thin and compressed, all united to give an expression of firmness and intellectuality. The solemn manner and long silence that he assumed as he calmly gazed upon the scene before him, was as full of eloquence as any words he could have uttered, and fell with unmistakable meaning upon the silent throng, upon whose faces still shone the light of the blazing council fire, reflecting no longer conflicting emotions, but one seemingly united all pervading sentiment. War and extermination to the whites. Apushamatahah’s observant eye read its deep signification. But nothing daunted, he began in a low but distinct tone of voice, which increased in volume and pathos as he became more and more animated. It was then that his eloquence also struck other sympathetic chords in that silent and attentive audience, and caused hundreds of hearts to pulsate faster under the magnetic influence of his words, and feel at once that before them stood, what many already knew, a great man. He also began his speech in the ancient method of opening an address (long since obsolete), thus: “O-mish-ke! A numpa tillofasih ish hakloh.” (Attention! Listen you to my brief remarks); and then continued in substance as follows:

“It was not my design in coming here to enter into a disputation with any one. But I appear before you, my warriors and my people not to throw in my plea against the accusations of Tecumseh; but to prevent your forming rash and dangerous resolutions upon things of highest importance, through the instigations of others. I have myself learned by experience, and I also see many of you, O Choctaws and Chickasaws, who have the same experience of years that I have, the injudicious steps of engaging in an enterprise be cause it is new. Nor do I stand up before you tonight to contradict the many facts alleged against the American people, or to raise my voice against them in useless accusations. The question before us now is not what wrongs they have inflicted upon our race, but what measures are best for us to adopt in regard to them; and though our race may have been unjustly treated and shamefully wronged by them, yet I shall not for that reason alone advise you to destroy them, unless it was just and expedient for you so to do; nor, would I advise you to forgive them, though worthy of your commiseration, unless I believe it would be to the interest of our common good. We should consult more in regard to our future welfare than our present. What people, my friends and countrymen, were so unwise and inconsiderate as to engage in a war of their own accord, when their own strength, and even with the aid of others, was judged unequal to the task? I well know causes often arise which force men to confront extremities, but my countrymen, those causes do not now exist. Reflect, therefore, I earnestly beseech you, before you act hastily in this great matter, arid consider with yourselves how greatly you will err if you injudiciously approve of and inconsiderately act upon Tecumseh’s advice. Remember the American people are now friendly disposed toward us. Surely you are convinced that the greatest good will result to us by the adoption of and adhering to those measures I have before recommended to you; and, without giving too great a scope to mercy or for aberrance, by which I could never permit myself to be seduced, I earnestly pray you to follow my advice in this weighty matter, and in following it resolve to adopt those expedients for our future welfare. My friends and fellow countrymen! You now have no just cause to declare war against the American people, or wreak your vengeance upon them as enemies, since they have ever manifested feelings of friendship towards you. It is besides inconsistent with your national glory and with your honor, as a people, to violate your solemn treaty; and a disgrace to the memory of your forefathers, to wage war against the American people merely to gratify the malice of the English.

“The war, which you are now contemplating against the Americans, is a flagrant breach of justice; yea, a fearful blemish on your honor and also that of your fathers, and which you will find if you will examine it carefully and judiciously, for bodes nothing but destruction to our entire race. It is a war against a people whose territories are now far greater than our own, and who are far better provided with all the necessary implements of war, with men, guns, horses, wealth, far beyond that of all our race combined, and where is the necessity or wisdom to make war upon such a people? Where is our hope of success, if thus weak and unprepared we should declare it against them? Let us not be deluded with the foolish hope that this war, if begun, will soon be over, even if we destroy all the whites within our territories, and lay waste their homes and fields. Far from it. It will be but the beginning of the end that terminates in the total destruction of our race. And though we will not permit ourselves to be made slaves, or, like inexperienced warriors, shudder at the thought of war, yet I am not so in sensible and inconsistent as to advise you to cowardly yield to the outrages of the whites, or willfully to connive at their unjust encroachments; but only not yet to have recourse to war, but to send ambassadors to our Great Father at Washington, and lay before him our grievances, without betraying too great eagerness for war, or manifesting any tokens of pusillanimity. Let us, therefore, my fellow countrymen form our resolutions with great caution and prudence upon a subject of such vast importance, and in which such fearful consequences may be involved.

“Heed not, O, my countrymen, the opinions of others to that extent as to involve your country in a war that destroys, its peace and endangers its future safety, prosperity and happiness. Reflect, ere it be too late, on the great uncertainty of war with the American people, and consider well, ere you engage in it, what the consequences will be if you should be disappointed in, your calculations and expectations. Be not deceived with illusive hopes. Hear me, O, my countrymen, if you begin this war it will end in calamities to us from which we are now free and at a distance; and upon whom of us they will fall, will only be determined by the uncertain and hazardous event. Be not, I pray you, guilty of rashness, which I never as yet have known you to be; there fore, I implore you, while healing measures are in the election of us all, not to break the treaty, nor violate your pledge of honor, but to submit our grievances, whatever they may be, to the Congress of the United States, according to the articles of the treaty existing between us and the American people. If not, I here invoke the Great Spirit, who takes-cognizance of oaths, to bear me witness that I shall endeavor to avenge myself upon the authors of this war, by whatever methods you shall set me an example. Remember we are a people who have never grown insolent with success, or be come abject in adversity; but let those who invite us to hazardous attempts by uttering our praise, also know that the pleasure of hearing has never elevated our spirits above our judgment, nor an endeavor to exasperate us by a flow of invectives to be provoked the sooner to compliance. From tempers equally balanced let it be known that we are warm in the field of battle, and cool in the hours of debate; the former, because a sense of duty has the greater influence over a sedate disposition, and magnanimity the keenest sense of shame; and though good we are at debate, still our education is not polite enough to teach us a contempt of laws, yet by its severity gives us so much good sense as never to disregard them.

“We are not a people so impertinently wise as to invalidate the preparations of our enemies by a plausible harangue, and then absolutely proceed to a contest; but we reckon the thoughts of the pale-faces to be of a similar cast with our own, and that hazardous contingencies are not to be determined by a speech. We always presume that the projects of our enemies are judiciously planned, and then we seriously prepare to defeat them. Nor do we found our success upon the hope that they will certainly blunder in their conduct, but upon the hope that we have omitted no proper steps for our own security. Such is the discipline, which our fathers have handed down to us; and by adhering to it, we have reaped many advantages. Let us, my countrymen, not forget it now, nor in short space of time precipitately determine a question in which so much is involved. It is indeed the duty of the prudent, so long as they are not injured, to delight in peace. But it is the duty of the brave, when injured, to lay peace aside, and to have recourse to arms; and when successful in these, to then lay them down again in peaceful quiet; thus never to be elevated above measure by success in war, nor delighted with the sweets of peace to suffer insults. For he who, apprehensive of losing the delight, sits indolently at ease, will soon be deprived of the enjoyment of that delight which interests his fears; and he whose passions are in flamed by military success, elevated too high by a treacherous confidence, hears no longer the dictates of judgment.

“Many are the schemes, though unadvisedly planned, through the more unreasonable conduct of an enemy, which turn out successful; but more numerous are those which, though seemingly founded on mature counsel, draw after them a disgraceful and opposite result. This proceeds from that great inequality of spirit with which an exploit is projected, and with which it is put into actual execution. For in council we resolve, surrounded with security; in execution we faint, through the prevalence of fear. Listen to the voice of prudence, oh, my countrymen, ere you rashly act. But do as you may, know this truth, enough for you to, know, I shall join our friends, the Americans, in this war.”

The observant eye of Tecumseh saw, ere Apushamatahah had closed, that the tide was turning against him; and, maddened at the unexpected eloquence, the bold and irresistible arguments of the Choctaw orator, the moment Apushamatahah had taken his seat he sprang to the center of the circle and, as a last effort to sustain his waning cause, cried out in a loud, bold and defiant tone of voice, “All who will follow me in this war throw your tomahawks into the air above your heads.” Instantly the air for many feet above was filled with the clashing of ascending, revolving and descending tomahawks, then all was hushed. Tecumseh then turned his piercing eyes upon Apushamtahah with a haughty air of triumph, and again took his seat. All eyes were instantly turned to where the fearless hero sat. “At once the mighty Choctaw, nothing daunted, sprang to his feet, gave the Choctaw hoyopatassuha (war-whoop), then, with the nimble bound of an antelope, leaped into the circle, and hurling his tomahawk into the air, shouted in a loud and defiant tone, “All who will follow me to victory and glory in this war let me also see your tomahawks in the air.”

Again the air seemed filled with tomahawks. Again silence prevailed. The test has been made, and what is the issue? The two forest orators have just counterpoised each others arguments, making an equal division in opinion among the vast assembly of warriors, which caused a strange alternative of hope in the one, and of apprehension in the other, of the now newly formed and opposing parties. Truly, that midnight council presented as wild and romantic a scene as can possibly be imagined, but which neither words nor pencil can justly express or paint; the wild glare of the burning log-heap alternately presenting in different shades the immediate surroundings in all their picturesque and romantic appearance; the voice of nature s unlettered and untutored orators alone disturbing the stillness of the night; friends and countrymen besieged by conflicting emotions expressed alone by the face. What a medley was there and then presented! Some incredulous, some convinced; some hopeful, some despairing; but all breasts heaving with the wildest, conflicting emotions. But I leave the reader to turn his thoughts upon it, and view it through the whole of its proceedings by the power of his imagination, which he can only do.

What now was to be done in this dilemma of a dubious issue? If half followed the suggestions of Tecumseh, and took sides with the English, and the other, those of Apushamatahah declaring for the Americans, it would virtually be civil war, and that should not, must not be. To settle the question, after many conflicting suggestions had been pro posed and rejected by first one and then the other of the two opposing parties, it was finally resolved to refer the matter to an aged Choctaw seer, living some distance away, and abide by his decision. The council adjourned to await his coming. A proper deputation was immediately sent to request his presence without delay, which returned in the evening of the second day accompanied by the old and venerable Choctaw hopaii (seer) whose white locks and wrinkled face proclaimed life’s journey had passed many years beyond man’s allotted period of three score and ten. As the twilight of the declining day approached, the council fire was replenished, and when night again had thrown over all her sable mantle, the council once more convened.

Again Tecumseh made the opening speech, rehearsing his designs and plans before the attentive seer and warrior host in strains of the most fascinating eloquence. Again followed Apushamatahah, who fell not behind his worthy competitor in native eloquence and logical argument. No other spoke, for both parties had mutually left the mooted question in the hands of the two great chiefs, statesmen and orators. When the two distinguished disputants had been respectively heard by the aged seer, he arose and slowly walked to the centre of the circle, gazed a moment over the silent but solicitous throng, and then said: “Assemble here tomorrow when the sun shall be yonder pointing to the zenith build a scaffold there pointing to the spot as high as my head; fill up the intervening space beneath with dry wood; bring also a red heifer two years old free of all disease, and tie her near the scaffold; and tomorrow the Great Spirit will decide for you this great question.”

On the next day the appointed hour found the multitude assembled; the altar erected; the wood prepared, and the sacrificial offering in waiting. The seer then ordered the heifer to be slain; the skin removed; the entrails taken out and placed some distance away; the carcase cut up into small pieces and laid upon the scaffold; he then applied a brand of fire to the dry wood under the scaffold; then commanded the vast multitudes, all, everyone, to stretch them selves upon the ground, faces to the earth, and thus to re main in profound silence until he ordered them to rise, which command was instantly obeyed; then seizing the bloody skin he stretched it upon the ground, hair downward, and quickly rolled himself up in it, and commenced a series of prayers and doleful lamentations, at the same time rolling himself backward and forward before the consuming sacrifice uttering his prayers and lamentations intermingled with dissonant groans fearful to be heard; and thus he continued until the altar and the flesh thereon were entirely consumed. Then freeing himself from the skin, he sprang to his feet and said: “Osh (the) Ho-che-to (Great) Shilup (Spirit) a-num-pul-ih (has spoken). Wak-a-yah (rise) ah-ma (and) Een (His) a-num-pa (message) hak-loh (hear). All leaped to their feet, and gathered in close circles around their venerated seer, who, pointing to the sky, exclaimed: “The Great Spirit tells me to warn you against the dark and evil designs of Tecumseh, and not to be deceived by his words; that his schemes are unwise; and if entered into by you, will bring you into trouble; that the Americans are our friends, and you must not take up the tomahawk against them; if you do, you will bring sorrow and desolation upon yourselves and nations. Choctaw and Chickasaws, obey the words of the Great Spirit. Enough! As oil upon the storm agitated waters of the sea, so fell the mandates of the Great Spirit upon the war agitated hearts of those forest warriors, and all was hushed to quiet; reason assumed again her sway; peace rejoiced triumphant, as all in harmony sought their forest homes; and thus the far scattered white settlers, in Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and Florida, and the western portion of Tennessee, escaped inevitable destruction; for, had Tecumseh been successful in uniting those five then powerful and warlike tribes into the adoption of his schemes scarcely a white person would have been left in all their broad territories to tell the tale of their complete extermination; since the wily Shawnee had laid off for each tribe its particular field of operation, before he had left his northern home to entice them into daring schemes. The whites were then but few scattered here and there, and at great distances apart, and could not have competed even with the Choctaws alone, as, they, at that time, numbered between thirty and forty thou sand warriors, and, besides, the blow would have fallen upon them when least expected and most unprepared.

Apushamatahah

But the long cherished hopes of Tecumseh were blasted, and Apushamatahah erected his trophies upon his defeat. Though greatly disappointed, yet not disheartened, Tecumseh at once set his footsteps toward the Muskogee Nation, now the State of Georgia.

Apushamatahah, who then lived near St. Stephens, now in Washington County, Alabama, turned his steps directly for that little town. Rumor of Tecumseh’s presence among the Choctaws and Chickasaws, and the council on the Tana-poh Ikbih River, had preceded him; and when he arrived at the little place he found it in a blaze of excitement, for a thousand exaggerated reports had but added to the conjecture as to the convening of the two tribes in common council, with the noted Shawnee Chief. But their fears were wholly allayed when the noble Apushamatahah, whose vera city none questioned, rode into the little town, and gave a short sketch of the proceedings at the council, and also proffered the services of himself and warriors to the Americans, which were cordially accepted by George S. Gaines, then United States agent to the Choctaws. And who, in company “with the noble chief, immediately hastened to Mobile, to in form General Flournoy of Apushamatahah’s proposition. To the astonishment of all, General Flournoy refused to accept the offer of the great Choctaw chief and warriors; while from every mouth loud curses and bitter denunciations were heard against his considered folly and seeming madness. With heavy heart and unpleasant forebodings Gaines returned to St. Stephens with Apushamatahah, whose grave silence but too plainly told the wound inflicted.

Fortunately, however, Flournoy reconsidered his refusal, and at once sent word to Gaines not only to accept the proposal of Apushamatahah in the name of the United States, but also to go immediately into the Choctaw Nation and secure the Choctaws as allies in the approaching war. There had been great apprehension lest the Choctaws would unite with the Muscogees and other disaffected tribes, as allies to the English; which they would, perhaps, have done, had Flournoy’s rejection of Apushamatahah’s proposal been given previous to the council held but a few days before. Apushamatahah, without delay, returned to his people then in the northern district of his Nation contiguous to the Chickasaw Nation, and there assembled his warriors in countries while Gaines hastened to Colonel John Pitchlynn’s house, near where the council with Tecumseh had but shortly adjourned, and where he was fortunate enough to meet Colonel McKee, United States Agent to the Chickasaws. At that time, the Choctaw Nation was divided into three districts, of which Apushamatahah was the ruling chief of the eastern, Apakfohlichihubih, of the northern, and Amosholihubih of the southern. Gaines at once left Colonel Pitchlynn’s and hastened to the Choctaw council, where he found Apushamatahah and several thousand of his warriors already Assembled; to whom Apushamatahah made a long and eloquent speech denouncing the ambitious views of Tecumseh, and extolling the friendship of the American people; then offered to lead all who would follow him, to victory and glory against the enemies of the Americans. As soon as he had concluded his speech, a warrior sprang from his seat on the ground, and striking his breast repeatedly with the palm of his right hand, shouted: “Choctaw siah! Tushka chitoh.siah aiena! Pimmi miko uno iakiyah. (A Choctaw I am. I am also a great warrior. I will follow our chief ). To which action and sentiment the whole council at once responded. In the mean time, McKee hastened with Colonel John Pitchlynn to the Chickasaw Nation, and by mutual efforts succeeded in assembling” them in council, and successfully secured them also as the allies to the Americans. Thus, by the firmness, influence and eloquence of the great and good. Apushamatahah, Tecumseh’s plans were thwarted, and those two then powerful tribes, the Choctaws and Chickasaws, secured as allies to the Americans, in the war with England in 1812, and also in that known as “The Creek war.”

In the council convened, in which the Choctaws declared in favor of the Americans against the English and the Muskogee’s, Apushamatahah publicly announced that, every Choctaw warrior who joined the Muskogee’s, should be shot, if ever they returned home. Still, there were thirty young warriors under the leadership of a sub-chief named Illi Shuah (Dead Stink), who joined the Muskogee’s. It was said; five or six lived to return home after the defeat of the Muscogees, all of whom Apushamatahah caused to be shot. But an aged Choctaw (long since deceased) whom I interviewed concerning the subject, stated that all the thirty warriors, who joined the Muskogee’s under Illi Shuah, were slain in battle to a man; but Illi Shuah escaped and finally returned home, but he did not remember whether Apushamatahah had him shot or not. In the “Creek war,” Apushamatahah, assisted General Jackson with seven hundred warriors; and in the “Battle of Orleans,” with five hundred. In both of which they proved themselves to be worthy allies in bravery and in the use of the deadly rifle.

The noble Apushamatahah descended not through a successive line of chiefs, but was of common parentage. Yet of whom it may be truly said: He was one of nature’s nobility, and born to command a man who raised himself from the obscurity of the wilderness unlettered and untaught; but by his superior native talents, undaunted bravery, noble generosity, unimpeachable integrity, un-assumed hospitality to the known and unknown, won the admiration, respect, confidence and love of his people; and also, of all the whites high or low, rich or poor who were personally acquainted with him. He was truly and justly the pride of the Choctaw people when living, and their veneration today though long dead. He acknowledged no paternity. Yet, his own statement in regard to his genealogy, as related to me by the aged Choctaws of the past, and is still mentioned by their descendants at the present day, with great pride, as characteristic of the manly independence of their honored chieftain, is worthy of record. It is in substance as follows:

On one occasion a deputation was sent by the Choctaws to Washington City to present the respects of their nation to the President of the United States who, at that time, was Andrew Jackson, and to assure him of their abiding- friend ship toward him as the “Great Chief” of the American people, and to also confer with him relative to the future interests and welfare of their nation. The renowned Apushamatahah was one of the deputation. A few days after their arrival in the city a reception was given to them, at which many of the cabinet and representative officers were present. Among the many and various questions that were asked of the different members of the delegation was the question. How they became so distinguished among their people? To which various answers were given, each telling his own story of the exploits which brought him out of obscurity and placed his name in the temple of human fame. Apushamatahah, up to this time, had said nothing. At length President Jackson requested the interpreter to ask him how he became such a great warrior and renowned chief. To which Apushamatahah coolly and with un-assumed indifference replied: “Tell the white chief it s none of his business.” This unexpected retort attracted the attention of all-present, and all eyes were at once turned upon the bold chief. Jackson, amused at the reply, and pleased at the manly independence of the noble chief, requested the interpreter to propound the same question again; which was done, but to which Apushamatahah seemed to give no heed. The curiosity of all being greatly excited, the question was asked still again. To which Apushamatahah then replied: “Well, if the white chief must know, tell him that Apushamatahahubih has neither father nor mother, nor kinsman upon the earth. Tell him that once upon a time, far away from here in the great forests of the Choctaw Nation, a dark cloud arose from the western horizon, and with astonishing velocity, traveled up the arched expanse; across its dark face the bright lightning played in incessant flashes, while the rolling thunder reverberated in muffled tones from hill to hill amid the vast solitudes of the surrounding forests. Swiftly and majestically it climbed the western sky, while the lightning flashed, followed by the thunders roar in successive peal after peal. In silence profound, till animate nature stood apart; soon the fearful cloud reached the zenith, then as quickly spread its dark mantle over the sky en tire, shutting out the light of the sun, and wrapping earth in midnight gloom, lighted only in lucid intervals by the lightning’s fitful glare, followed by peals of thunder in deafening roar. Then burst the cloud and rose the wind; and while falling rains and howling winds, lightning’s gleam and thunders roar, in wild confusion blended, a blinding flash blazed athwart the sky as if to view the scene, then hurled its strength against a mighty oak an ancient monarch of the woods that for ages had defied the storm with his boasted power and cleft it in equal twain from utmost top to lowest bottom; when, lo! From its riven trunk leaped a mighty man; in stature, perfect; in wisdom, profound; in bravery, unequalled a full-fledged warrior. Twas Apushamatahahubih.”

In November 1812, Apushamatahah visited General Claiborne. When he approached the General’s tent, he was received by the lieutenant on guard, who invited him to drink, that “civilized” method of the whites to prove the sincere emotions of the heart in regard to friendship. Apushamatahah answered only with a look of contempt. He recognized no equal with one epaulette. When Gen Claiborne walked in, the Choctaw Chieftan shook him by the hand and proudly said, as to one equal, “Chief, I will drink with you.” He was six feet two inches in height, of powerful frame and Herculean strength, and with features after the finest models of the antique, composed, dignified, and seductive in his deportment, and was the most remarkable man the Choctaws ever produced since the days of Chahtah, the Great Miko of their traditional past. He was sometimes called Koi Hosh, (The Panther); and sometimes, Ossi Hosh; sometimes Oka Chilohonfah (Falling Water). The two first alluding to his quick movements and daring exploits in war, and the latter, to the sonorous and musical intonations of his voice.

Sam Dale, the renowned scout of General Andrew Jackson in the “Creek war” of 1812, and as famous in his day, as Kit Carson in the narrative of Gen. Fremont in his exploring expedition over the Rocky Mountains, stated that he had heard Tecumseh and the Prophet of the Shawnees; Bill Weatherford of the Muskogee’s; Big Warrior of the Cherokees, and Apokfohlichubih of the Choctaws, besides the most distinguished American orators in congress, but never one who had such music in his tones, such energy in his manner, and such power over his audience as Apushamatahah, the Choctaw chief, patriot and warrior.

Many characteristic anecdotes are related of him, and of which I will mention a few: A feud once existed between him and another Choctaw chief of the Yazoo district, and it was generally believed that when they met their tomahawks would settle the difference between them. One day his rival was seen approaching in company with a large party of warriors; and on a nearer approach, manifested great agitation irresolutely grasping his tomahawk Apushamatahah, as soon as he discovered him shouted his challenging war whoop, rushed toward him with his long hunting knife in his hand, then suddenly stopped, and with a smile of the utmost con tempt, cried out “Hushi osh chishikta! Katihma ish wun-nichih! Hosh mahli Keyumahlih. Ea, ho bak! Ea!” (Leaf of the red oak! Why, do you tremble? The wind blows not. Go, coward! Go!) The word, hobak is considered by the Choctaws, as a word of the greatest reproach and most unpardonable offense that could possibly be applied to a man, its true signification being an eunuch.

Apushamatahah was very sensitive at the appearance of anything that even bore the appearance of oppression. A few soldiers, at that day, were stationed at the agency among the Choctaws, as they are and always have been among all Indians, as a bright (?) manifestation of the great confidence (?) the whites cherished in the integrity and friendship of all Indians; and one of the soldiers being addicted to drunkenness, and at one time having- become boisterously drunk,, he was tied to a tree, for the want of that necessary appendage to an Indian Agency, as well as to all towns among-the whites, a jail or guard house, until he became sober. Apushamatahah happening to pass by and seeing” the soldier, tied asked him of what he was guilty, that he should be placed in so humiliating a condition; being told the cause, he at once released the unfortunate man, exclaiming, “Is that all? Many good warriors get drunk.”

Apushamatahah, in unison with the ancient custom of the Choctaws, had two wives. Being asked if he did not consider it wrong for a man to have more than one living-wife, he replied: Certainly not. Should not every woman be allowed the privilege of having a husband, as well as a man a wife? And how can every one have a husband when there are more women than men? Our Great Father had the Choctaws counted last year, and it was ascertained that there were more women than men, and if a man were allowed but one wife many of our women would have no husbands. Surely, the women should have equal chances with the men in that particular.”

During the Creek war of 1814, in which Apushamatahah was engaged with eight hundred of his warriors as allies of the United States, as before stated, a small company of Choctaw women, among whom was the wife of Apushamatahah, visited their husbands and friends then in the American army in the Creek Nation. A white soldier grossly insulted the wife of the distinguished Choctaw chief, for which the justly indignant chief knocked him down with the hilt of his sword, instead of plunging it through his body, as he should have done. Being arrested for the just and meritorious act, and asked by the commanding general the reasons for his act, he fearlessly answered: “He insulted my wife, and I knocked the insolent dog down; but had you. General, have insulted her as that common soldier did, I would have used the point upon you instead of the hilt, in, resenting an insult offered to my wife.” And he would have been as good as his word; for a Choctaw then, as now, is not slow in resenting any insult offered to the female portion of his family, and his work is quick and sure; and had not the noble Apushamatahah regarded the soldier who insulted his wife, as too contemptible a creature for the point of his-sword, he would have plunged it through his body without a moment s hesitation; and that he only knocked him down with the hilt, is sufficient evidence that he did not regard! Him worthy its point.

Apushamatahah was exceedingly fond of engaging in that ancient and time-honored amusement, the famous To-lih (ball play); and in which the Choctaws, as well as the southern portion of their race, took great delight a gymnasium indeed, where were exhibited and tried the various, physical powers of man, unsurpassed on earth; and in which even those of ancient Greece and Rome dwindle into insignificance.

While battling with his warriors for the interests of the Americans under Andrew Jackson, in 1814. General Jackson presented to Apushamatahah a complete military suit and sword, as worn by the American generals; which he wore with manly and becoming dignity until the close of the war; which, after the close, he took off and hung up in his cabin,, and never afterwards put on the suit ; but donned his native garb and once more became the Apushamatahah of his people. Having become wearied, however, in looking upon the white man s insignia that feeble representation of true-greatness in the opinion of the Choctaw hero he took the: suit from its resting place, rolled it up and fastened it to one end of a long rope, then attached the other end to his belt; and then, with quiver full of arrows hung over his left shoulder and bow in hand, marched through various parts of his village, dragging the insignificant badge of meritorious distinction on the ground behind him; at each house he approached, he shot a chicken, if one was found ; took it up and. inserted its head under his belt; then he continued his silent, walk, and seeking another house, there shot another, chicken, also slipped its head under his belt: and thus he continued his march from house to house with a solemn and silent gravity, taxing each a chicken until he had shot as many as he could slip heads under the belt. The owners of the chickens said nothing, knowing that some fun was ahead. He then walked to an untaxed house with his load of chickens dangling from his belt, had them nicely dressed and cooked, then invited all from whom he had taken a chicken to come and partake of the feast he had thus unceremoniously prepared for them. They went and had a jolly time, Apushamatahah figuring as the gayest among the gay. He left his suit lying upon the ground before the door of the house at which he deposited the chickens, a frail memento of human greatness with its hopes departed.

In 1823, Apushamatahah, then about sixty years of age walked about 80 miles from his home (being too poor to own a horse, and too proud to borrow one) to attend a council of his Nation. Mr. John Pitchlynn, then United States interpreter to the Choctaws, and Mr. Ward, United States agent, (with both of whom I was in boyhood personally acquainted), were present at the council. At the adjournment of the council, Mr. Ward suggested to Mr. Pitchlynn that they purchase a horse for the old chief. Mr. Pitchlynn readily acquiesced in the proposition, but with the proviso that Apushamatahah must pledge his word that he would not sell the horse for whiskey. Apushamatahah cheerfully gave the pledge, received the horse and departed for his distant home highly elated with his unexpected good fortune. A few months after he visited the agency, and Ward discovered that he was again minus a horse, and learned, upon inquiry that he had lost the presented horse in betting him on a ball-play. Ward at once accused him of violating his pledged word, which Apushamatahah as firmly denied. “But you promised,” continued Ward, “that you would not sell the horse.” “True I did;” retorted the venerable old chief. “But I did not promise you and my good friend, John Pitchlynn, that I would not bet him in a game of ball. Ward conceded the victory to Apushamatahah, and chided him no more.

In 1824, this great and good man visited Washington City in company with other Choctaw chiefs, as delegates of their Nation to the United States government; at which time he made the following remarks to the Secretary of War, which were written down as he spoke them.

“Father, I have been here many days, but have 1 not talked, have been sick. I belong to another district, different from these my companions and countrymen. You have no doubt heard of me, I am Apushamatahahubih. When in my own country, I often looked towards this Council House, and desired to see it, I have come, but I am in trouble, and would tell my sorrows; for I feel as a little child reclining in the bend of its father s arms, and looks up into his face in childish confidence to tell him of its troubles; and I would now recline in the bend of your arm, and trustingly look in your face, therefore hear my words.

“When at my distant home in my own native land, I heard that men had been appointed to talk to us; I refrained from speaking there, as I preferred to come here and speak; therefore I am here today. I can boastingly say, and in so doing speak the truth, that none of my ancestors, nor my present Nation, ever fought against the United States. As a Nation of people, we have always been friendly, and ever listened to the applications of the American People. We have given of our country to them until it has become very small. I came here years ago when a young man to see my Father Jefferson. He then told me if ever we got into trouble we must come and tell him, and he would help us. We are in trouble, and have come; but I will now let another talk.”

The above was but a preliminary to a speech he intended to make, and which, had he lived to have delivered, would have proved to his hearers in Washington his great native eloquence, which had been so long and much eulogized by the whites who had often heard him around the council fires of his Nation.

In conversation with the noble General Lafayette during the same visit to Washington City Apushamatahah closed with the following: “This is the first time I have seen you, and I feel it will be the last. The earth will separate us for ever farewell!” How prophetic! He died but a few days after. When stretched upon his bed of death, fully conscious of his near approaching end, he calmly turned his eyes upon the faces of the Choctaw delegates standing around him, and said: “I am dying, and will never return again to our native and loved land. But you will go back to our distant homes; and as you journey you will see the wild flowers of the forests and hear the songs of the happy birds of the woods, but Apushamatahahubih will see and hear them no more.

When you return home you will be asked, Apushama tahah katimmaho? (Where is Apushamatahah?), and you will answer, Illitok (dead to be). And it will fall upon their & ears as the sound of a mighty oak falling in the solitude of the woods.” His dying words were “Illi siah makinli sa paknaka tanapoh chitoh tokalichih” (As soon as I am dead shoot off the big-guns above). The request of the dying-hero was strictly complied with. The minute-guns were fired on Capitol Hill as the solemn and imposing procession of half a mile in length marched to the cemetery that silent and melancholy habitation of the dead and there the great Choctaw Chief and warrior found a grave where all distinctions cease and where neither flatteries, nor censures, nor proffered wealth, nor honors, could seduce his incorruptible heart.

His surrounding brother chiefs erected a monument over the grave of their distinguished chieftain, with the following meritorious epitaph, “Apushamatahah, a Choctaw Chief; lies here. This monument to his memory is erected by his brother chiefs who were associated with him in a delegation from their nation, in the year 1824, to the government of the United States. Apushamatahah was a warrior of great distinction. He was wise in council, eloquent to an extraordinary degree; and on all occasions, and under all circumstances, the white man s friend. He died in Washington on the 24th of December, 1824, of the croup, in the 60th year of his age.”

Apushamatahah had only one son, who was named Johnson. He moved with his people to their present homes, and served them in the capacity of Prosecuting Attorney for many years, in Apushamatahah District. He lived to prove himself worthy of his distinguished father, and in many respects was a true scion of the parent trunk.

Truly, if the adventures through which Apushamatahah passed had been preserved, they would have furnished alone abundant material for all the writers of romance in the United States, for years.

It is conceded by all who knew him, that he was the most renowned warrior and influential chief of the Choctaw Nation, since their acquaintance with the whites. He was a man who never surrendered nor disguised his opinions and convictions upon any subject whatever. His recoil from all that which was mean, selfish, false, and unjust resembled the impulse with which, the strongly bent bow recoils from the curve to which the strong arm of the experienced archer has forced it.

Nor did Tecumseh, whom I would not pass unheeded by, fall below Apushamatahah; and he too may deservedly have a place among the greatest of the North American Indian chiefs; and truthfully may it be said of him, his arm pervaded, his vigilance detected, his spirit animated, and his generosity won, in all directions, and he ever maintained the standing he acquired among all his race everywhere.

That Tecumseh was a man of tender feeling s and noble principles is sufficiently attested in his actions at Fort Miami. When the white prisoners, taken at Fort Meigs in 1813, were confined in Fort Miami by General Proctor, some of them were being slain by the Indians in the presence of Proctor, and his officers, when suddenly a thrilling voice in the Shawnee language was heard, and soon Tecumseh was seen approaching on his horse at full speed, and springing to the ground where two Indians were in the act of killing an American prisoner, he hurled them both to the ground, then brandishing his tomahawk he threatened death to the Indian that dared to kill another prisoner. All knew too well that the fearless chieftain threatened not in vain, and the killing instantly ceased. Then he called out in the loudest tone of voice, “Where is Proctor?” but at the same instant, seeing him standing a few rods distant, he sternly demanded of him why he permitted the murdering of the American prisoners? To which Proctor replied: “I cannot govern your warriors.” Upon which Tecumseh fixed his keen and penetrating eyes upon him a moment, and then, with the utmost contempt, cried out, “Begone! You are not fit to command; go put on a petticoat,” an epithet denoting the Indian s supreme disgust and highest contempt.

To Tecumseh the idea of selling land was an absurdity. On one occasion, he cried out in unfeigned astonishment: “What! Sell land ! As well sell air and water. The Great Spirit gave them in common to all the air to breathe, the water to drink, and the land to live upon you may as well sell air and water as sell land;” and in the same light did all the North American Indians view it, and hence their opposition to land severalty which they cannot understand nor comprehend.

Shawnee Tribe

Tecumseh, signifying Flying Arrow, (it is said) belonged to the clan called Panther of the Kickapoo tribe. His mother was a Muskogee and his father a Shawnee, though born among the Muskogee’s in the South, and afterwards moved to Ohio among his own tribe and settled upon the banks of the Sciota River, but while upon the journey Tecumseh was born.

The Kickapoos of the present day are supposed to be a branch of the Shawnee tribe proper, as the traditions of both give nearly the same accounts of their union and separation, besides their language is said to identically the same.

The Shawnee traditions declare their ancestors formerly dwelt in a foreign land, but the reason for the abandonment of their ancient sites is not stated.

But when the day appointed for their exodus rolled around, they were informed by the Great Spirit through their prophets, to march in a body to the shore of a sea, and then select a leader from the multitude, who would be clothed by the Great Spirit with that supernatural power that the waters of the sea, as soon as he touched them, would separate and he would conduct them on dry land safely across to another country. Having reached the sea, a selection was made but the incredulity of the chosen caused him to refuse the honor as well as the responsibility; many having been chosen with like results, it began to awaken no little trepidation, when one, who was selected from a clan called The Turtle Clan, accepted the position, and confidence was again restored. All thing’s being duly prepared to resume their journey, still to many of uncertain issue, their chosen leader boldly placed himself at the head of the host, and fearlessly stepped into the sea, upon which the waters at once divided to the right and to the left, and they safely walked across on the bottom and thus came to this country; reminding one of the account given by Holy Writ of Moses and the Jewish host encountering the waters of the Red Sea. To what else can the Shawnee tradition point, but the crossing of the Red Sea by the Israelites in their exodus from Egypt and their flight before Pharaoh and his pursuing army?

The Shawnees had another tradition whose shades of coloring seem greatly Jewish. It is, that the Shawnees were originally divided into twelve tribes, each one having a distinct and separate name; and each of which was afterwards sub-divided into clans., called The Eagle, The Panther, The Turtle, etc., the animals whose names they bore constituting their coat-of-arms, or totem. Their traditions also affirm two of the original tribes became extinct, as also were their names; while the other ten are still extant, though but four are wholly distinct, and are called The Ma-kas-tra-ke, The Pick-a-way, The Kick-a-poo, and the Chil-i-coth-e Clans; the other six, according to their tradition, having been incorporated with the four. It has been stated by the early missionaries to them, that to a late date their council houses were separated into four divisions, each one of which was assigned to the occupancy of each one of the tribes separate and apart from each other, and was invariably so occupied. And that it was impossible for the whites to discriminate in the least whatever, yet the Indians themselves could tell to which clan any one belonged as soon as they saw him.

Truly, what an interesting and instructive volume would the early history of the North American Indians have been, with all the various traditions of their migrations, vicissitudes and changes, had they been preserved?

Tecumesh Killed