Ottawa Indians, Ottawa First Nation, Ottawa Nation, Ottawa People (from ǎdāwe, ‘to trade’, `to buy and sell,’ a term common to the Cree, Algonkin, Nipissing, Montagnais, Ottawa, and Chippewa, and applied to the Ottawa because in early traditional times and also during the historic period they were noted among their neighbors as intertribal traders and barterers, dealing chiefly in cornmeal, sunflower oil, furs and skins, rugs or mats, tobacco, and medicinal roots and herbs).

Ottawa Tribe History

On French river, near its mouth, on Georgian bay, Champlain in 1615 met 300 men of a tribe which, he said, “we call les cheueux releuez.” Of these he said that their arms consisted only of the bow and arrow, a buckler of boiled leather, and the club; that they wore no breechclout, and that their bodies were much tattooed in many fashions and designs; that their faces were painted in diverse colors, their noses pierced, and their ears bordered with trinkets. The chief of this band gave Champlain to understand that they had come to that place to dry huckleberries to be used in winter when nothing else was available. In the following year Champlain left the Huron villages and visited the “Cheueux releuez” (Ottawa), living westward from the Hurons, and he said that they were very joyous at “seeing us again.” This last expression seemingly shows that those whom he had met on French river in the preceding year lived where he now visited them. He said that the Cheueux releuez waged war against the Mascoutens (here erroneously called by the Huron name Asistagueronon), dwelling 10 days’ journey from them; he found this tribe populous; the majority of the men were great warriors, hunters, and fishermen, and were governed by many chiefs who ruled each in his own country or district; they planted corn and other things; they went into many regions 400 or 500 leagues away to trade; they made a kind of mat which served them for Turkish rugs; the women had their bodies covered, while those of the men were uncovered, saving a robe of fur like a mantle, which was worn in winter but usually discarded in summer; the women lived very well with their husbands; at the catamenial period the women retired into small lodges, where they had no company of men and where food and drink were brought to them. This people asked Champlain to aid them against their enemies on the shore of the fresh-water sea, distant 200 leagues from them.

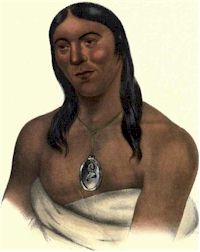

One who is talked of or Augustin Hamelin, Jr

In the Jesuit Relation for 1667, Father Le Mercier, reporting Father Allouez, treated the Ottawa, Kiskakon, and Ottawa Sinago as a single tribe, because they had the same language and together formed a common town. He adds that the Ottawa (Outaoüacs) claimed that the great river (Ottawa?) belonged to them, and that no other nation might navigate it without their consent. It was, for this reason, he continues, that although very different in nationality all those who went to the French to trade bore the name Ottawa, under whose auspices the journey was undertaken. He adds that the ancient habitat of the Ottawa had been a quarter of Lake Huron, whence the fear of the Iroquois drove them, and whither were borne all their longings, as it were, to their native country. Of the Ottawa the Father says: “They were little disposed toward the faith, for they were too much given to idolatry, superstitions, fables, polygamy, looseness of the marriage tie, and to all manner of license, which caused them to drop all native decency.”

According to tradition 1 the Ottawa, Chippewa, and Potawatomi tribes of the Algonquian family were formerly one people who came from some point north of the great lakes and separated at Mackinaw, Michigan. The Ottawa were located by the earliest writers and also by tradition on Manitoulin island and along the north and south shore of Georgian bay.

Father Dablon, superior of the missions of the Upper Algonkin in 1670, said: “We call these people Upper Algonkin to distinguish them from the Lower Algonkin who are lower down, in the vicinity of Tadousac and Quebec. People commonly give them the name Ottawa, because, of more than 30 different tribes which are found in these countries, the first that descended to the French settlements were the Ottawa, whose name remained afterward attached to all the others.” The Father adds that the Saulteurs, or Pahoüiting8ach Irini, whose native country was at the Sault Sainte Marie, numbering 500 souls, had adopted three other tribes, making to then, a cession of the rights of their own native country, and also that the people who were called Noquet ranged, for the purpose of hunting, along the south side of Lake Superior, whence they originally came; and the Chippewa (Outcibous) and the Marameg from the north side of the same lake, which they regarded as their native land. The Ottawa were at Chagaouamigong or La Pointe de Sainte Esprit in 1670 2.

Father Le Mercier 3, speaking of a flotilla of canoes from the “upper nations,” says that they were “partly Ondataouaouat, of the Algonquine language, whom we call ‘les Cheueux releuez.’ ” And in the Relation for 1665 the same Father says of the Ottawa that they were better merchants than warriors.

In a letter of 1723, Father Sébastien Rasles says that he learned while among the Ottawa that they attributed to themselves an origin as senseless as it was ridiculous. They informed him that they were derived from three families, each composed of 500 persons. The first was that of Michabou (see Nanabozho), or the Great Hare, representing him to be a gigantic man who laid nets in 18 fathoms of water which reached only to his armpits and who was born in the island of Michilimackinac, and formed the earth and invented fish-nets after carefully watching a spider weaving its web for taking flies; among other things he decreed that his descendants should burn their dead and scatter their ashes in the air, for if they failed to do this, the snow would cover the ground continuously and the lakes would remain frozen. The second family was that of the Namepich, or Carp, which, having spawned its eggs on the shore of a river and the sun casting its rays on them, a woman was thus formed from whom they claimed descent. The third family was that of the Bear’s paw, but no explanation was given of the manner in which its genesis took place. But when a bear was killed a feast of its own flesh was given in its honor and an address was made to it in these terms: “Have thou no thoughts against us, because we have killed thee; thou hast sense and courage; thou seest that our children are suffering from hunger; they love thee, and so wish to cause thee to enter their bodies; and is it not a glorious thing to be eaten by the children of captains?” The first two families bury their dead 4.

It has been stated by Charlevoix and others that when they first became known to the French they lived on Ottawa river. This, however, is an error, due to the twofold use of the name, the one generic and the other specific, as is evident from the statements by Champlain and the Jesuit Relations 5; this early home was north and west of the Huron territory. No doubt Ottawa river, which they frequently visited and were among the first western tribes to navigate in trading expeditions to the French settlements, was named from the Ottawa generically so called, not from the specific people named Ottawa. There is unquestioned documentary evidence that as early as 1635 a portion of the Ottawa lived on Manitoulin island. Father Vimont, in the Jesuit Relation for 1640, 34,1858, says that “south of the Amnikwa [Beaver Nation] there is an island [Manitoulin] in that fresh water sea [Lake Huron], about 30 leagues in length, inhabited by the Outaouan [Ottawa], who are a people come from the nation of the Standing Hair [Cheueux Releuez].” This information he received from Nicolet, who visited the Ottawa there in 1635.

On the

Ottawa and Chippewa

Head Chief of the Kenisteno Nation

of 1660, on a large island approximating the location of Manitoulin island, the “natio surrectormn capillorum,” i. e. the Cheveux Releves, or Ottawa, is placed. They were allies and firm friends of the French and the Hurons, and conducted an active trade between the western tribes and the French. After the destruction of the Hurons, in 1648-49, the Iroquois turned their arms against the Ottawa, who fled with a remnant of the Hurons to the islands at the entrance of Green bay, where the Potawatomi, who had preceded the Ottawa and settled on these islands, received the fugitives with open arms and granted them a home. However, their residence here was but temporary, as they moved westward a few years afterward, a part going to Keweenaw bay, where they were found in 1660 by Father Menard, while another part fled with a band of Hurons to the Mississippi, and settled on an island near the entrance of Lake Pepin. Driven away by the Sioux, whom they had unwisely attacked, they moved north to Black river, Wis., at the head of which the Hurons built a fort, while the Ottawa pushed eastward and settled on the shore of Chaquamegon bay. They were soon followed by the missionaries, who established among there the mission of St Esprit. Harassed by the Sioux, and a promise of protection by the French having been obtained, they returned in 1670-71 to Manitoulin island in Lake Huron.

According to the records, Father Allouez, in 1668-69, succeeded in converting the Kiskakon band at Chaquamegon, but the Sinago and Keinouche remained deaf to his appeals. On their return to Manitoulin the French fathers established among them the mission of St Simon. There is a tradition that Lac Court Oreilles was formerly called Ottawa lake because a hand of the Ottawa dwelt on its shores, until they were forced to move by the attacks of the Sioux 6. Their stay on Manitoulin island was brief; by 1680 most of them had joined the Hurons at Mackinaw, about the station established by Margqutte in 1671.

The two tribes lived together until about 1700, when the Hurons removed to the vicinity of Detroit, while a portion of the Ottawa about this time seems to have obtained a foothold on the west shore of Lake Huron between Saginaw bay and Detroit, where the Potawatomi were probably in close union with them. Four divisions of the tribe were represented by a deputy at the treaty signed at Montreal in 1700. The band which had moved to the southeast part of the lower Michigan peninsula returned to Mackinaw about 1706. Soon afterward the chief seat of a portion of the tribe was fixed at Waganakisi (L’Arbre Croche), near the lower end of Lake Michigan. From this point they spread in every direction, the majority settling along the east shore of the lake, as far south as St Joseph river, while a few found their way into south Wisconsin and north east Illinois. In the north they shared Manitoulin island and the north shore of Lake Huron with the Chippewa, and in the south east their villages alternated with those of their old allies the Hurons, now called Wyandot, along the shore of Lake Erie from Detroit to the vicinity of Beaver creek in Pennsylvania. They took an active part in all the Indian wars of that region up to the close of the War of 1812. The celebrated chief Pontiac was a member of this tribe, and Pontiac’s war of 1763, waged chiefly around Detroit, is a prominent event in their history. A small part of the tribe which refused to submit to the authority of the United States removed to Canada, and together with some Chippewa and Potawatomi, is now settled on Walpole island in Lake St Clair. The other Ottawa in Canadian territory are on Manitoulin and Cockburn islands and the adjacent shore of Lake Huron.

All the Ottawa lands along the west shore of Lake Michigan were ceded by various treaties, ending with the Chicago treaty of Sept. 26, 1833, wherein they agreed to remove to lands granted them on Missouri river in the north east corner of Kansas. Other bands, known as the Ottawa of Blanchard’s fork of Great Auglaize river, and of Roche de Bmuf on Maumee river, resided in Ohio, but these removed west of the Mississippi about 1832 and are now living in Oklahoma. The great body, however, remained in the lower peninsula of Michigan, where they are still found scattered in a number of small villages and settlements.

In his Histoire du Canada 7, Fr Sagard mentions a people whom he calls “la nation du bois.” He met two canoe loads of these Indians in a village of the Nipissing, describing them as belonging to a very distant inland tribe, dwelling he thought toward the “sea of the south,” which was probably Lake Ontario. He says that they were dependents of the Ottawa (Cheueux Releuez) and formed with them as it were a single tribe. The men were entirely naked, at which the Hurons, he says, were apparently greatly shocked, although scarcely less indecent themselves. Their faces were gaily painted in many colors in grease, some with one side in green and the other in red; others seemed to have the face covered with a natural lace, perfectly wellmade, and others in still different styles. He says the Hurons had not the pretty work nor the invention of the many small toys and trinkets which this “Gens de Bois” had. This tribe has not yet been definitely identified, but it may have been one of the three tribes mentioned by Sagard in his Dictionnaire de la Langve Hvronne, under the rubric “nations,” as dependents of the Ottawa (Andatahoüat), namely, the Chisérhonon, Squierhonon, and Hoindarhonon.

Charlevoix says the Ottawa were one of the rudest nations of Canada, cruel and barbarous to an unusual degree and sometimes guilty of cannibalism. Bacqueville de la Potherie 8 says they were formerly very rude, but by intercourse with the Hurons they have become more intelligent, imitating their valor, making themselves formidable to all the tribes with whom they were at enmity and respected by those with whom they were in alliance. It was said of them in 1859: “This people is still advancing in agricultural pursuits; they may he said to have entirely abandoned the chase; all of them live in good, comfortable log cabins; have fields inclosed with rail fences, and own domestic animals.” The Ottawa were expert canoe men; as a means of defense they sometimes built forts, probably similar to those of the Hurons.

Ottawa Nation

The population of the different Ottawa groups is not known with certainty. In 1906 the Chippewa and Ottawa on Manitoulin and Cockburn Islands, Canada, were 1,497, of whom about half were Ottawa; there were 197 Ottawa under the Seneca School, Okla., and in Michigan 5,587 scattered Chippewa and Ottawa in 1900, of whom about two-thirds are Ottawa. The total is therefore about 4,700.

The following are or were Ottawa villages:

- Aegakotcheising

- Anamiewatigong

- Apontigoumy

- Machonee

- Manistee

- Menawzhetaunaung

- Meshkemau

- Michilimackinac

- Middle Village

- Obidgewong (mixed)

- Oquanoxa

- Roche de Boeuf

- Saint Simon (mission)

- Shabawywyagun

- Tushquegan

- Waganakisi

- Walpole Island

- Waugau

- Wolf Rapids

Citations:

- see Chippewa[↩]

- Jes. Rel. 1670, 83, 1858[↩]

- Jes. Rel. 1654[↩]

- Lettres Edif., iv, 106, 1819[↩]

- See Shea in Charlevoix, New France, ii, 270, 1866[↩]

- Brunson in Wis. Hist. Coll., iv[↩]

- Sagard, Histoire du Canada, 1, 190, 1836[↩]

- Bacqueville de la Potherie, Hist. Am. Sept., 1753[↩]

Discover more from Access Genealogy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.