The Creek woman was short in stature, but well formed. Her cheeks were rather high, but her features were generally regular and pretty. Her brow was high and arched, her eyes large, black and languishing, expressive of modesty and diffidence. Her feet and hands were small, and the latter exquisitely shaped. 1780: The warrior was larger than the ordinary race of Europeans, often above six feet in height, but was invariably well formed, erect in his carriage, and graceful in every movement. They were proud, haughty and arrogant; brave and valiant in war; ambitious of conquest; restless, and perpetually exercising their arms, yet magnanimous and merciful to a vanquished Indian enemy who afterwards sought their friendship and protection. 1 Encountering fatigue with ease, they were great travellers, and sometimes went three or four hundred leagues on a hunting expedition.” Formerly they were cruel, but at the present day they are brave, yet peaceable, when not forced to abandon their character.” 2

Like all other Indians, they were fond of ornaments, which consisted of stones, beads, wampum, porcupine quills, eagles’ feathers, beautiful plumes, and earrings of various descriptions. The higher classes were often fantastic in their wearing apparel. Sometimes a warrior put on a ruffled shirt of fine linen, and went out with no other garment except a flap of blue broadcloth, with buskins made of the same. The stillapica or moccasin, embroidered with beads, adorned the feet of the better classes. Mantles of good broadcloth, of a blue or scarlet color, decorated with fringe and lace, and hung with round silver or brass buttons, were worn by those who could afford them. When they desired to be particularly gay, vermillion was freely applied to the face, neck and arms. Again, the skin was often inscribed with hieroglyphics and representations of the sun, moon, stars and various animals. 3 This was performed by puncturing the parts with gar’s tooth, and rubbing in a dye made of the drippings of rich pine roots. These characters were inscribed during youth, and frequently in manhood, every time that a warrior distinguished himself in slaying the enemy. Hence when he was unfortunately taken prisoner, he was severely punished in proportion to the marks upon his skin, by which he was known to have shed the blood of many of the kindred of those into whose hands he had fallen. 4 The Creeks wore many ornaments of silver. Crescents or gorgets, very massive, suspended around the neck by ribbons, reposed upon the breast, while the arms, fingers, hats, and even sometimes the necks, had silver bands around them.

The females wore a petticoat which reached to the middle of the leg. The waistcoat, or wrapper, made of calico, printed linen, or fine cloth, ornamented with lace and beads, enveloped the upper part of the body. They never wore boots or stockings, but their buskins reached to the middle of the leg. Their hair, black, long and rather coarse, was plaited in wreaths, and ordinarily turned up and fastened in a crown with a silver band. This description of dress and ornaments were worn only by the better classes. The others were more upon the primitive Indian order. They were fond of music, both vocal and instrumental; but the instruments they used were of an inferior kind, such as the tambour, rattle-gourd, and a kind of flute, made of the joint of a cane or the tibia of the deer’s leg. Dancing was practiced to a great extent, and they employed an endless variety of steps. 5

Their most manly and important game was the “ball play.” It was the most exciting and interesting game imaginable, and was the admiration of all the curious and learned travellers who witnessed it. The warriors of one town challenged those of another, and they agreed to meet at one town, or the other, as may have been decided. For several days previous to the time, those who intended to engage in the amusement took medicine, as though they were going to war. The night immediately preceding was spent in dancing and other ceremonious preparations. On the morning of the play, they painted and decorated themselves. In the meantime, the news had spread abroad in the neighboring towns, which had collected, at the place designated, an immense concourse of men, women, and children — the young and the gay — the old and the grave — together with hundreds of ponies, Indian merchandise, extra wearing apparel, and various articles brought there to stake upon the result.

The players were all nearly naked, wearing only a piece of cloth called “flap.” They advanced towards the immense plain upon which they were presently to exhibit astonishing feats of strength and agility. From eighty to a hundred men were usually on a side. They now approached each other, and were first seen at the distance of a quarter of a mile apart, but their war songs and yells had previously been heard. Intense excitement and anxiety were depicted upon the countenance of the immense throng of spectators. Presently the parties appeared in full trot, as if about to encounter fiercely in fight. They met and soon became intermingled together, dancing and stamping, while a dreadful artillery of noise and shouts went up and rent the air. An awful silence then succeeded. The players retired from each other, and fell back one hundred and fifty yards from the centre. Thus they were three hundred yards apart. In the centre were erected two poles, between which the ball must pass to count one. Every warrior was provided with two rackets or hurls, of singular construction, resembling a ladle or hoop-net with handles nearly three feet long. The handle was of wood, and the netting of the thongs of raw hide or the tendons of an animal. The play was commenced by a ball, covered with buckskin, being thrown in the air. The players rushed together with a mighty shock, and he who caught the ball between his two rackets, ran off with it and hurled it again in the air, endeavoring to throw it between the poles in the direction of the town to which he belonged. They seized hold of each other’s limbs and hair, tumbled each other over, first trampled upon those that were down, and did everything to obtain the ball, and afterwards to make him who had it, drop it before he could make a successful throw. The game was usually from twelve to twenty. It was kept up for hours, and during the time the players used the greatest exertions, exhibited the most infatuated devotion to their side, were often severely hurt, and sometimes killed, in the rough and unfeeling scramble which prevailed. It sometimes happened that the inhabitants of a town gamed away all their ponies, jewelry and wearing apparel, even stripping themselves upon the issue of the ball play. In the meantime, the women were constantly on the alert with vessels and gourds filled with water, watching every opportunity to supply the players. 6

If a Creek warrior wished to marry, he sent his sister, mother, or some female relation, to the female relations of the girl whom he loved. Her female relations then consulted the uncles, and if none the brothers, on the maternal side, who decided upon the case. If it was an agreeable alliance, the bridegroom was informed of it, and he sent, soon after, a blanket and articles of clothing to the female part of the family of the bride. If they received these presents, the match was made, and the man was at liberty to go to the house of his wife as soon as he deemed it proper. When he had built a residence, produced a crop, gathered it in, made a hunt and brought home the game, and tendered a general delivery of all to the girl, then they were considered man and wife.

Divorce was at the choice of either party. The man, however, had the advantage, for he could again marry another woman if he wished; but the woman was obliged to lead a life of celibacy until the Boosketuh, or Green Corn Dance, was over. Marriage gave no right to the husband over the property of the wife, or the control or management of the children which he might have by her.

Adultery was punished by the family of the husband, who collected together, consulted and agreed on the course to pursue. One-half of them then went to the house of the woman, and the other half to the residence of the guilty warrior. They apprehended, stripped, and beat them with long poles, until they were insensible. Then they cropped off their ears, and sometimes their noses, with knives, the edges of which they made rough and saw-like. The hair of the woman was carried in triumph to the square. Strange to say, they generally recovered from this inhuman treatment. If one of the offenders escaped, satisfaction was taken by similar punishment inflicted upon the nearest relative. If both of the parties fled unpunished, and the party aggrieved returned home and laid down the poles, the offense was considered satisfied. But one family in the Creek nation had authority to take up the poles the second time, and that was the Ho-tul-gee, or family of the Wind. The parties might absent themselves until the Boosketuh was over, and then they were free from punishment for this and all other offenses, except murder, which had to be atoned for by death upon the guilty one or his nearest relative. 7

The Creeks buried their dead in the earth, in a square pit, under the bed where the deceased lay in his house. The grave was lined on the sides with cypress bark, like the curbing of a well. The corpse, before it became cold, was drawn up with cords, and made to assume a squatting position; and in this manner it was placed in the grave and covered with earth. The gun, tomahawk, pipe, and other articles of the deceased, were buried with him. 8

In 1777, Bartram found, in the Creek nation, fifty towns, with a population of eleven thousand, which lay upon the rivers Coosa, Tallapoosa, Alabama, Chattahoochie and Flint, and the prominent Creeks which flowed into them. The Muscogee was the national language, although in some of these towns, the Uchee or Savannah, Alabama, Natchez and Shawnee tongues prevailed. But the Muscogee was called, by the traders, the “mother tongue,” while the others mentioned were termed the “stinkard lingo.” 9

The general council of the nation was always held in the principal town, in the centre of which was a large public square, with three cabins of different sizes in each angle, making twelve in all. Four avenues led into the square. The cabins, capable of containing sixty persons each, were so situated that from one of them a person might see into the others. One belonging to the Grand Chief fronted the rising sun, to remind him that he should watch the interests of his people. Near it was the grand cabin, where the councils were held. In the opposite angle, three others belonged to the old men, and faced the setting sun, to remind them that they were growing feeble, and should not go to war. In the two remaining corners were the cabins of the different Chiefs of the nation, the dimensions of which were in proportion to the rank and services of those Chiefs. The whole number in the square was painted red, except those facing the west, which were white, symbolical of virtue and old age. The former, during war, were decorated with wooden pieces sustaining a chain of rings of wood. This was a sign of grief, and told the warriors they should hold themselves in readiness, for their country needed their services. These chains were replaced by garlands of ivy leaves during peace.

In the month of May, annually, the Chiefs and principal Indians assembled in the large square formed by these houses, to deliberate upon all subjects of general interest. When they were organized they remained in the square until the council broke up. Here they legislated, eat and slept. During the session, no person, except the principal Chiefs, could approach within less than twenty feet of the grand cabin. The women prepared the food, and deposited it at a prescribed distance, when it was borne to the grand cabin by the subordinate Chiefs. In the center of the square was a fire constantly burning. At sunset the council adjourned for the day, and then the young people of both sexes danced around this fire until a certain hour. As soon as the sun appeared above the horizon, a drumbeat called the Chiefs to the duties of the day. 10

Besides this National Legislature, each principal town in the nation had its separate public buildings, as do the States of this American Union; and like them, regulated their own local affairs. The public square at Auttose, upon the Tallapoosa, in 1777, consisted of four square buildings, of the same dimensions and uniform in shape, so situated as to form a tetragon, enclosing an area of an half acre. Four passages, of equal width at the corners, admitted persons into it. The frames of these buildings were of wood, but a mud plaster, inside and out, was employed to form neat walls; except two feet all around under the eaves, left open to admit light and air. One of them was the council house, where the Micco (King), Chiefs and Warriors, with the white citizens, who had business, daily assembled to hear and decide upon all grievances, adopt measures for the better government of the people, and the improvement of the town, and to receive ambassadors from other towns. This building was enclosed on three sides, while a partition, from end to end, divided it into two apartments, the back one of which was totally dark, having only three arched holes large enough for a person to crawl into. It was a sanctuary of priest craft, in which were deposited physic-pots, rattles, chaplets of deer’s hoofs, the great pipe of peace, the imperial eagle-tail standard, displayed like an open fan, attached to which a staff as white and clean as it could be scoured. The front part of the building was open like a piazza, divided into three apartments — breast high — each containing three rows of seats, rising one above the other, for the legislators. The other three buildings fronting the square were similar to the one just described, except that they had no sanctuary, and served to accommodate the spectators; they were also used for banqueting houses.

The pillars and walls of the houses of the square abounded with sculptures and caricature paintings, representing men in different ludicrous attitudes; some with the human shape, having the heads of the duck, turkey, bear, fox, wolf and deer. Again, these animals were represented with the human head. These designs were not ill executed, and the outlines were bold and well proportioned. The pillars of the council house were ingeniously formed in the likeness of vast speckled snakes ascending–the Auttoses being of the Snake family. 11

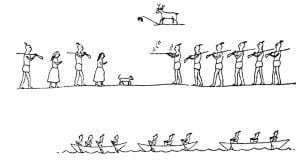

Rude paintings were quite common among the Creeks, and they often conveyed ideas by drawings. No people could present a more comprehensive view of the topography of a country, with which they were acquainted, than the Creeks could, in a few moments, by drawing upon the ground. Barnard Roman, a Captain in the British Army, saw at Hoopa Ulla, a Choctaw town, not far from Mobile, the following drawing, executed by the Creeks, which had fallen into the possession of the Choctaws. This represents that ten Creek warriors, of the family of the Deer, went into the Choctaw country in three canoes; that six of them landed, and in marching along a path, met two Choctaw men, two women and a dog; that the Creeks killed and scalped them. The scalp, in the deer’s foot, implies the horror of the action to the whole Deer family. 12

The great council house at Auttose, was appropriated to much the same purpose as the square, but was more private. It was a vast conical building, capable of accommodating many hundred people. Those appointed to take care of it, daily swept clean, and provided canes for fuel and to give lights. Besides using this rotunda for political purposes, of a private nature, the inhabitants of Auttose were accustomed to take their “black drink” in it. The officer who had charge of this ceremony ordered the cacina tea to be prepared under an open shed opposite the door of the council house; he directed bundles of dry cane to be brought in, which were previously split in pieces of two feet long. “They were now placed obliquely across upon one another on the floor, forming a spiral line round about the great centre pillar, eighteen inches in thickness. This spiral line, spreading as it proceeded round and round, often repeated from right to left, every revolution increased its diameter, and at length extended to the distance of ten or twelve feet from the centre, according to the time the assembly was to continue.” By the time these preparations were completed, it was night, and the assembly had taken their seats. The outer end of the spiral line was fired. It gradually crept round the entire pillar, with the course of the sun, feeding on the cane, and affording a bright and cheerful light. The aged Chiefs above the other, sat upon their cane sofas, which were elevated one above the other, and fixed against the back side of the house, opposite the door. The white people and Indians of confederate towns sat, in like order, on the left — a transverse range of pillars, supporting a thin clay wall, breast high, separating them. The King’s seat was in front; back of it were the seats of the head warriors, and those of a subordinate condition. Two middle-aged men now entered at the door, bearing large conch shells full of black drink. They advanced with slow, uniform and steady steps, with eyes elevated, and singing in a low tone. Coming within a few feet of the King, they stopped, and rested their shells on little tables. Presently they took them up again, crossed each other, and advanced obsequiously. One presented his shell to the King, and the other to the principal man among the white audience. As soon as they raised them to their mouths the attendants uttered two notes — hoo-ojah! and a-lu-yah! — which they spun out as long as they could hold their breath. As long as the notes continued, so long did the person drink or hold the shell to his mouth. In this manner all the assembly were served with the “black drink.” But when the drinking begun, tobacco, contained in pouches made of the skins of the wild cat, otter, bear and rattlesnake, was distributed among the assembly, together with pipes, and a general smoking commenced. The King began first, with a few whiffs from the great pipe, blowing it ceremoniously, first toward the sun, next toward the four cardinal points, and then toward the white audience. Then the attendants passed this pipe to others of distinction. In this manner, these dignified and singular people occupied some hours in the night, until the spiral line of canes was consumed, which was a signal for retiring. 13

Twenty-one years after the visit of Bartram to the Creek nation, Col. Benjamin Hawkins, to whom Washington had confided important trusts in relation to the tribes south of the Ohio, penetrated these wilds. He found the public buildings, at that period similar to those already described, with, however, some exceptions, which may have been the result of a slight change of ancient customs.

Every town had a separate government, and public buildings for business and pleasure, with a presiding officer, who was called a King, by the traders, and a Micco, by the Indians. This functionary received all public characters, heard their talks, laid them before his people, and, in return, delivered the talk of his own town. He was always chosen from some noted family. The Micco of Tookabatcha was of the Eagle tribe (Lum-ul-gee.) When they were put into office, they held their stations for life, and when dead, were succeeded by their nephews. The Micco could select an assistant when he became infirm, or for other causes, subject to the approval of the principal men of the town. They generally bore the name of the town which they governed, as Cusseta Micco, Tookabatcha Micco, etc.

“Choo-co-thluc-co, (big house) the town house or public square, consists of four buildings of one story, facing each other, forty by sixteen feet, eight feet pitch; the entrance at each corner. Each building is a wooden frame supported on posts set in the ground, covered with slabs, open in front like a piazza, divided into three rooms, the back and ends clayed up to the plates. Each division is divided lengthwise into two seats. The front, two feet high, extending back half way, covered with reed mats or slabs; then a rise of one foot and it extends back, covered in like manner, to the side of the building. On these seats they lie or sit at pleasure.

The Rank of the Buildings Which Form the Square

“1st. Mic-ul-gee in-too-pau, the Micco’s cabin. This fronts the east, and is occupied by those of the highest rank. The center of the building is always occupied by the Micco of the town, by the Agent for Indian affairs, when he pays a visit to a town, by the Miccos of other towns, and by respectable white people.

“The division to the right is occupied by the Mic-ug-gee (Miccos, there being several so called in every town, from custom, the origin of which is unknown), and the councilors. These two classes give their advice in relation to war, and are, in fact, the principal councilors.

“The division to the left is occupied by the E-ne-hau-ulgee (people second in command, the head of whom is called by the traders second man.) These have the direction of the public works appertaining to the town, such as the public buildings, building houses in town for new settlers, or working in the fields. They are particularly charged with the ceremony of the ã-ce, (a decoction of the cassine yupon, called by the traders black drink), under the direction of the Micco.

“2d. Tus-tun-nug-ul-gee in-too-pau, the warriors’ cabin. This fronts the south. The head warrior sits at the end of the cabin, and in his division the great warriors sit beside each other. The next in rank sit in the center division, and the young warriors in the third. The rise is regular by merit from the third to the first division. The Great Warrior, for this is the title of the head warrior, is appointed by the Micco and councilors from among the greatest war characters.

“When a young man is trained up and appears well qualified for the fatigues and hardships of war, and is promising, the Micco appoints him a governor, or, as the name imports, a leader (Is-te-puc-cau-chau), and if he distinguishes himself they elevate him to the center cabin. A man who distinguishes himself repeatedly in warlike enterprises, arrives to the rank of the Great Leader (Is-te-puc-cau-chau-thlucco) This title, though greatly coveted, is seldom attained, as it requires a long course of years, and great and numerous successes in war.

“The second class of warriors is the Tusse-ki-ul-gee. All who go to war, and are in company when a scalp is taken, get a war-name. The leader reports their conduct and they receive a name accordingly. This is the Tus-se-o-chif-co or war-name. The term leader, as used by the Indians, is a proper one. The war parties all march in Indian file, with the leader in front, until coming on hostile ground. He is then in the rear.

“3d. Is-te-chaguc-ul-gee in-too-pau, the cabin of the beloved men. This fronts the north. There are a great many men who have been war leaders and who, although of various ranks, have become estimable in long course of public service. They sit themselves on the right division of the cabin of the Micco, and are his councilors. The family of the Micco, and great men who have distinguished themselves occupy this cabin of the Beloved Men.

“4th. Hut-te-mau-hug-gee, the cabin of the young people and their associates. This fronts the west.

The Convention of the Town

“The Micco, councilors and warriors meet every day in the public square, sit and drink of the black tea, talk of the news, the public and domestic concerns, smoke their pipes, and play Thla-chal-litch-cau (roll the bullet). Here all complaints are introduced, attended to and redressed.

“5th. Chooc-ofau-thluc-co, the rotundo or assembly room, called by the traders “hot house.” This is near the square, and is constructed after the following manner: Eight posts are driven into the ground, forming an octagon of thirty feet in diameter. They are twelve feet high, and large enough to support the roof. On these, five or six logs are placed, of a side, drawn in as they rise. On these, long poles or rafters, to suit the height of the building, are laid, the upper ends forming a point, and the lower-ends, projecting out siz feet from the octagon, and resting on the posts, five feet high, placed in a circle round the octagon, with plates on them, to which the rafters are tied with splits. The rafters are near together and fastened with splits. These are covered with clay, and that of pine bark. The wall, six feet from the octagon, is clayed up. They have a small door, with a small portico curved round for five or six feet, then into the house.

“The space between the octagon and wall is one entire sofa, where the visitors lie or sit at pleasure. It is covered with reed, mat or splits.

“In the centre of the room, on a small rise, the fire is made of dry cane, or dry old pine slabs, split fine, and laid in a spiral line. This is the assembly room for all people, old and young. They assemble every night and amuse themselves with dancing, singing or conversation. And here, sometimes, in very cold weather, the old and naked sleep.

“In all transactions which require secrecy, the rulers meet here, make their fire, deliberate and decide.” 14

A very interesting festival, common not only to the Creeks, but to many other tribes, will now be described. As Col. Hawkins was, in all respects, one of the most conscientious and reliable men that ever lived, his account, like the preceding, will be copied in his own style. Of the many descriptions of the Green Corn Dance, in our possession, that by the honest and indefatigable Creek Agent is the most minute and most readily understood.

Boos-ke-tau

“The Creeks celebrate this festival in the months of July and August. The precise time is fixed by the Micco and councilors, and is sooner or later, as the state of affairs of the town or the early or lateness of their corn will suit. In Cussetuh this ceremony lasts for eight days. In some towns of less note it is but four days.

“FIRST DAY.

“In the morning the warriors clear the yard of the square, and sprinkle white sand, when the black drink is made. The fire-maker makes the fire as early in the morning as he can, by friction. The warriors cut and bring into the square four logs, each as long as a man can cover by extending his two arms. These are placed in the center of the square, end to end, forming a cross, the outer ends pointed to the cardinal points; in the center of the cross the new fire is made. During the first four days they burn out these first four logs.

“The Pin-e-bun-gau (turkey dance) is danced by the women of the Turkey tribe, and while they are dancing the possau is brewed. This is a powerful emetic. It is drank from twelve o’clock to the middle of the afternoon. After this, Toc-co-yula-gau (tad-pole) is danced by four women and four men. In the evening the men dance E-ne-hou-bun-gau (the dance of the people second in command). This they dance till daylight.

“SECOND DAY.

“About ten o’clock the women dance Its-ho-bun-gau (gun dance). After twelve o’clock the men go to the new fire, take some of the ashes, rub them on the chin, neck and abdomen, and jump head foremost into the river, and then return into the square. The women having prepared the new corn for the feast, the men take some of it and rub it between their hands, then on their faces and breasts, and then they feast.

“THIRD DAY.

“The men sit in the square.

“FOURTH DAY.

“The women go early in the morning and get the new fire, clean out their hearths, sprinkle them with sand, and make their fires. The men finish burning out the first four logs, and they take ashes, rub them on their chin, neck and abdomen, and they go into the water. This day they eat salt, and they dance Obungauchapco (the long dance).

“FIFTH DAY.

” They get four new logs, and place them as on the first day, and they drink the black drink.

“SIXTH AND SEVENTH DAYS,

“They remain in the square.

“EIGHTH DAY.

“They get two large pots, and their physic plants, the names of which are:

Mic-ca-ho-you-e-juh,

Co-hal-le-wau-gea,

Toloh,

Chofeinsack-cau-fuck-au,

A-che-nau,

Cho-fe-mus-see,

Cap-pau-pos-cau,

Hillis-hutke,

Chu-lis-sau (the roots),

To-te-cuh-chooe-his-see,

Tuck-thlau-lus-te,

Welau-nuh,

To-te-cul-hil-lis-so-wau,

Oak-chon-utch-co.

These plants are put in pots and beat up with water. The chemists, E-lic-chul-gee, called by the traders physic-makers, blow into it through a small reed, and then it is drank by the men and rubbed over their joints till the afternoon.

“They collect old corn cobs and pine burs, put them into a pot and burn them to ashes. Four very young virgins bring ashes from their houses and stir them up. The men take white clay and mix it with water in two pans. One pan of clay and one of the ashes are carried to the cabin of the Micco, and the other two to that of the warriors. They then rub themselves with the clay and ashes. Two men, appointed to that office, bring some flowers of tobacco of a small kind, Itch-au-chee-le-pue-pug-gee, or as the name imports, the old man’s tobacco, which was prepared on the first day and put in a pan in the cabin of the Micco, and they gave a little of it to every one present.

“The Micco and councilors then go four times around the fire, and every time they face the east they throw some of the flowers into the fire. They then go, and stand to the west. The warriors then repeat the same ceremony.

“A cane is stuck up at the cabin of the Micco, with two white feathers at the end of it. One of the fish tribe (Thlot-logulgee) takes it, just as the sun goes down, and goes off to the river, followed by all. When he gets half way down the river he gives the death whoop, which he repeats four times between the square and the water’s edge. Here they all place themselves as thick as they can stand near the edge of the water. He sticks up the cane at the water’s edge, and they all put a grain of the old man’s tobacco on their heads and in each ear. Then, at a signal given four different times, they throw some into the river; and every man, at a signal, plunges into the river and picks up four stones from the bottom. With these they cross themselves on their breasts four times, each time throwing a stone into the river and giving the death whoop. They then wash themselves, take up the cane and feathers, return and stick it up in the square, and visit through the town. At night they dance O-bun-gau-hadjo (mad dance), and this finishes the ceremony.

“This happy institution of the Boos-ke-tau restores man to himself, to his family, and to his nation. It is a general amnesty, which not only absolves the Indians from all crimes, murder alone excepted, but seems to bring guilt itself into oblivion.” 15

With some slight variations, the Green Corn Dance was thus celebrated throughout the Creek confederacy. At the town of Tookabatcha, however, it will be recollected, that on the fourth day, the Indians introduced the “brass plates.” At Coosawda, the principal town of the Alabamas, they celebrated a Boosketau of four days each, of mulberries and beans, when these fruits respectively ripened. 16

James Adair, a man of learning and enterprise, lived more than thirty years among the Chickasaws, and had frequent intercourse with the nations of the Muscogees, Cherokees and Choctaws, commencing in 1735. He was an Englishman, and was connected with the extensive commerce carried on at an early period with these tribes. While among the Chickasaws, with whom he first began to reside in 1744, he wrote a large work on aboriginal history. When he returned to his mother country, he published this work, “American Indians,” a ponderous volume of near five hundred the pages, at London, in 1775. Well acquainted with the Hebrew language, and having, in his long residence with the Indians, acquired an accurate knowledge of their tongue, he devoted the larger portion of his work to prove that the latter were originally Hebrews, and were a portion of the lost tribes of Israel. He asserts, that at the Boosketaus of the Creeks and other tribes within the limits of Alabama, the warriors danced around the holy fire, during which the elder priest invoked the Great Spirit, while the others responded Halelu! Halelu! then Haleluiah! Haleluyah! He is ingenious in his arguments, and introduces many strange things to prove, to his own satisfaction, that the Indians were descendants of the Jews — seeking, throughout two hundred pages, to assimilate their language, manners and customs. He formed his beliefs that they were originally the same people, upon their division into tribes, worship of Jehovah, notions of theocracy, belief in the ministration of angels, language and dialects, manner of computing time, their Prophets and High Priests, festivals, fasts and religious rites, daily sacrifices, ablutions and anointing, laws of uncleanliness, abstinence from unclean things, marriages, divorces, and punishments for adultery, other punishments, their towns of refuge, purification and ceremony preparatory to war, their ornaments, manner of curing the sick, burial of the dead, mourning for the dead, raising seed to a deceased brother, choice of names adapted to their circumstances and times, their own traditions, and the accounts of our English writers, and the testimony which the Spanish and other authors have given concerning the primitive inhabitants of Peru and Mexico.

He insists that in nothing do they differ from the Jews except that rite of circumcision, which he contends, their ancestors dispensed with, after they became lost from the other tribes, on account of the danger and inconvenience of the execution of that rite, to those engaged in a hunting and roving life. That when the Israelites were forty years in the wilderness, even then they attempted to dispense with circumcision, but Joshua, by his stern authority, enforced its observance. The difference in food, mode of living and climate are relied upon by Adair, to account for the difference in the color, between the Jew and Indian, and also why the one has hair upon the body and the other has not. 17

Adair is by no means alone in his opinion of the descent of the American Indians. Other writers, who have lived among these people, have arrived at the same conclusion. Many of the old Indian countrymen with whom we have conversed believe in theor Jewish origin, while others are of a different opinion. Abram Mordecai, an intelligent Jew, who dwelt fifty years in the Creek nation, confidently believed that the Indians were originally of his people, and he asserted that in their Green Corn Dances he had heard them often utter in grateful tones the word yavoyaha! yavoyaha! He was always informed by the Indians that this meant Jehovah, or the Great Spirit, and that they were then returning thanks for the abundant harvest with which they were blessed. 18

Colonel Hawkins concludes his account of the religious and war ceremonies of the Creek Indians as follows:

“At the age of from fifteen to seventeen, the ceremony of initiating youth to manhood is performed. It is called the Boosketau, in like manner as the annual Boosketau of the nation. A youth of the proper age gathers two handfuls of the Sou-watch-cau, a very bitter root, which he eats a whole day. Then he steeps the leaves in water and drinks it. In the dusk of evening he eats two or three spoonfuls of boiled grits. This is repeated for four days, and during this time he remains in a house. The Sou-watch-cau has the effect of intoxicating and maddening. The fourth day he goes out, but must put on a pair of new moccasins (stillapicas). For twelve moons he abstains from eating bucks, except old ones, and from turkey cocks, fowls, peas and salt. During this period he must not pick his ears or scratch his head with his fingers, but use a small stick. For four moons he must have a fire to himself to cook his food, and a little girl, a virgin, may cook for him. His food is boiled grits. The fifth moon any person may cook for him, but he must serve himself first, and use one pan and spoon. Every new moon he drinks for four days the possau (button snakeroot), an emetic, and abstains for three days from all food, except in the evening a little boiled grits (humpetuh hutke). The twelfth moon he performs, for four days, what he commenced with on the first. The fifth day he comes out of his house, gathers corncobs, burns them to ashes, and with these rubs his body all over. At the end of this moon he sweats under blankets, then goes into water, and thus ends the ceremony. This ceremony is sometimes extended to four, six or eight moons, or even to twelve days only, but the course is the same.

“During the whole of this ceremony the physic is administered by the Is-te-puc-cau-chau-thlucco (Great Leader), who, in speaking of the youth under initiation says,

“I am physicing him”–Boo-se-ji-jite saut li-to mise-cha). Or ‘I am teaching him all that it is proper for him to know’–(nauk o-mul-gau e-muc-e-thli-jite saut litomise cha).

The youth during this initiation does not touch any one except young persons, who are under a like course with himself. And if he dreams, he drinks the possau.” 19

Whenever Creeks were forced to take up arms, the Tustenuggee caused to be displayed in the public places a club, part of which was painted red. He sent it to each subordinate Chief, accompanied with a number of pieces of wood, equal to the number of days that it would take that Chief to present himself at the rendezvous. The War Chief alone had the power of appointing that day. When this club had arrived, each Chief caused a drum to be beat before the grand cabin where he resided. All the inhabitants immediately presented themselves. He informed them of the day and place where he intended to kindle his fire. He repaired to that place before the appointed day, and rubbed two sticks together, which produced fire. He kindled it in the midst of a square, formed by posts, sufficiently extended to contain the number of warriors he desired to assemble. As soon as the day dawned, the Chief placed himself between the two posts which fronted the east, and held in his hand a package of small sticks. When a warrior entered the enclosure, which was open only on one side, he threw down a stick and continued until they were all gone, the number of sticks being equal to the number of warriors he required. Those who presented themselves afterwards could not be admitted, and they returned home to hunt, indicating the place where they could be found if there services were needed. Those who thus tardily presented themselves were badly received at home, and were reproached for the slight desire they had testified to defend their country.

The warriors who were in the enclosure remained there, and for three days took the medicine of war. Their wives brought them their arms, and all things requisite for the campaign, and deposited them three hundred yards in front of the square, together with a little bag of parched cornmeal, an ounce of which would make a pint of broth. 20 It was only necessary to mix it with water, and in five minutes it became as thick as soup cooked by a fire. Two ounces would sustain a man twenty-four hours. It was indispensable, for, during a war expedition, the party could not kill game.

The three days of medicine having expired, the Chief departed with his warriors to the rendezvous appointed by the Grand Chief. Independently of this medicine, which was taken by all, each subordinate Chief had his particular talisman, which he carefully carried about his person. It consisted of a small bag, in which were a few stones and some pieces of cloth which had been taken from the garments of the Grand Chief, in the return from some former war. If the subordinate Chief forgot his bag he was deprived of his rank, and remained a common soldier during the whole expedition. 1778: The Grand Chief presented himself at the rendezvous on the appointed day, and he was sure to find there the assembled warriors. He then placed himself at the head of the army, making all necessary arrangements, without being obliged to rendezvous on account of any one. Being certain that his discipline and orders would be punctually enforced, he marched with confidence against the enemy. When they were ready to march, each subordinate Chief was compelled to be provided with the liquor which they called the medicine of war; and the Creeks placed it in such a degree of confidence that it was difficult for a War Chief to collect his army if they were deprived of it. He would be exposed to great danger if he should be forced to do battle without having satisfied this necessity. If he should suffer defeat, which would certainly be the case, beacuse the warriors would have no confidence in themselves, but be overcome by their own superstitious fears, he would be responsible for all misfortunes.

There were two medicines, the great and the little, and it remained for the Chief to designate which of these should be used. The warrior, when he had partaken of the great medicine, believed himself invulnerable. The little medicine served, in his eyes, to diminish danger. Full of confidence in the statements of his Chief, the latter easily persuaded him that he gave him only the little medicine it was because the circumstances did not require the other. These medicines being purgative in their nature, the warrior found himself less endangered by the wounds which he might receive. The Creeks had still another means of diminishing the danger of their wounds, which consisted in fighting almost naked, for it is well known that the particles of cloth remaining in wounds render them more difficult to heal. 1778: They observed during war the most rigorous discipline, for they neither eat nor drink without an order from the Chief. They dispensed with drinking even while passing along the bank of a river, because circumstances had obliged their Chief to forbid it, under pain of depriving them of their medicine of war, or, rather, of the influence of their talisman. When an enemy compelled them to take up arms they never returned home without giving him battle, and at least taking a few scalps. These may be compared to the colors among civilized troops, for when a warrior had killed an enemy he took his scalp, which was an honorable trophy for him to return to his nation. They removed them from the head of an enemy with great skill and dexterity. They were not at all the same values, but were classed, and it was for the Chiefs, who were the judges of all achievements, to decide the value of each. It was in proportion to the number and value of these scalps that a Creek advanced in civil as well as militry rank. It was necessary, in order to occupy a station of any importance, to taken at least seven of them. If a young Creek, having been at war, returned without a single scalp, he contimued to bear the name of his mother and could not marry, but if he returned with a scalp, the principle men assembled at the grand cabin to give him a name, that he might abandon that of his mother. They judged of the value of the scalp by the dangers experienced in capturing it, and the greater these dangers, the more considerable were the title and advancement derived from it, by its owner.

In time of battle, the Great Chief commonly placed himself in the centre of the army, and sent reinforcements wherever danger appeared most pressing. When he perceived that his forces were repulsed and feared that they would yield entirely to the efforts of the enemy, he advanced in person, and combated hand to hand. A cry, repeated on all sides, informed the warriors of the danger to which a Chief was exposed. Immediately the corps de reserve came together, and advanced to the spot where the Grand Chief was, in order to force the enemy to abandon him. Should he be dead, they would all die rather than abandon his body to the enemy, without first securing his scalp. They attached such value to this relic, and so much disgrace to the loss of it, that when the danger was very great, and they were not able to prevent his body from falling into the hands of the enemy, the warrior who was nearest to the dead Chief, took his scalp and fled, at the same time raising a cry, known only among the savages. He then went to the spot which the deceased Chief had indicated, as the place of rendezvous, should his army be beaten. All the subordinate Chiefs, being made aware of his death by this cry, made dispositions to retreat; and this being effected, they proceeded to the election of his successor, before taking any other measures. The Creeks were very warlike, and were not rebuffed by defeat. On the morrow, after an unfortunate battle, they advanced with renewed intrepidity, to encounter their enemy anew.

When they advanced towards an enemy, they marched one after another, the Chief of the party being at the head. They arranged themselves in such a manner as to place the foot of every one in the track made by the first. The last one concealed even that track with grass. By this means they kept from the enemy any knowledge of their number. When they made a halt, for the purpose of encamping, they formed a circle, leaving a passage only large enough to admit a single man. They sat cross-legged, and each one had his gun by his side. The Chief faced the entrance of the circle, and no warrior could go out without his permission. At the time of sleeping he gave a signal and after that no person could stir. Rising was performed at the same signal. It was ordinarily the Grand Chief who marked out positions, and placed sentinels to watch for the security of the army. He always had a great number of runners, both before and behind, so that an army was rarely surprised. They, on the contrary, conducted wars against the Europeans entirely by sudden attacks, and they were very dangerous to those who were not aware of them. 21

When the Creeks returned from war with captives, they marched into their town with shouts and the firing of guns. They stripped them naked and put on their feet bear-skins moccasins, with the hair exposed. The punishment was always left to the women, who examined their bodies for the their war-marks. Sometimes the young warriors who had none of these honorable inscriptions were released and used as slaves. But the warrior of middle age, even those of advanced years, suffered death by fire. The victim’s arms were pinioned, and one end of a strong grape vine tied around his neck, while the other was fastened to the top of a war-pole, so as to allow him to track around a circle of fifteen yards. To secure his scalp against fire, tough clay was placed upon his head. The immense throng of spectators were now filled with delight, and eager to witness the inhuman spectacle. The suffering warrior was not dismayed, but, with a manly and insulting voice, sang the war-song. The women then made a furious onset with flaming torches, dripping with hot black pitch, and applied them to his back, and all parts of his body. Suffering excruciating pain, he rushed from the pole with the fury of a wild beast, kicking, biting and trampling his cruel assailants under foot. But fresh numbers came on, and after a long time, and when he was nearly burned to his vitals, they ceased and poured water upon him to relieve him — only to prolong their sport. They renewed their tortures, when with champing teeth and sparkling eye-balls, he once more broke through the demon throng to the extent of his rope, and acted every part that the deepest desperation could prompt. Then he died. His head was scalped, his body quartered, and the limbs carried over the town in triumph. 22

An enumeration of the towns found in the Creek nation by Col. Hawkins, in 1798, will conclude the notice of the manners and customs of these remarkable people, though, hereafter, they will often be mentioned, in reference to their commerce and wars with the Americans.

Towns Among the Upper Creeks

- Tal-e-se, derived from Tal-o-fau, a town, and e-se, taken– situated in the fork of the Eufaube, upon the left bank of the Tallapoosa.

- Took-a-batcha, opposite Tallese.

- Auttose, on the left side of Tallapoosa, a few miles below the latter.

- Ho-ith-le-waule–from h-ith-le, war, and waule, divide–right bank of the Tallapoosa, five miles below Auttose.

- Foosce-hat-che-fooso-wau, a bird, and hat-che, tail two miles below the latter, on the right bank.

- Coo-loo-me was below and adjoining the latter.

- E-cun-hut-ke-e-cun-nau, earth, and hut-ke, white–below Coo-loo-me, on the same side of the Tallapoosa.

- Sou-van-no-gee, left bank of the river.

- Mook-lau-sau, a mile below the latter, same side.

- Coo-sau-dee, three miles below the confluence of the Coosa and Tallapoosa, on the west bank of the Alabama.

- E-cun-chate-e-cun-na, earth, chate, red–(now a part of the city of Montgomery). (1798)

- Too-was-sau, three miles below, same side of the Alabama.

- Pau-woe-te, two miles below the latter, on the same side.

- Au-tau-gee, right side of the Alabama, near the mouth of the creek of the same name.

- Tus-ke-gee–in the fork of the Coosa and Tallapoosa, on the east bank of the former–the old site of forts Toulouse and Jackson.

- Hoochoice and Hookchoie-ooche, towns just above the latter.

- O-che-a-po-fau-o-che-ub, hickory tree, and po-fau, in or among–east bank of the Coosa, on the plain just below the city of Wetumpka.

- We-wo-cau-we-wau, water, wo-cau, barking or roaring–on a creek of that name, fifteen miles above the latter.

- Puc-cun-tal-lau-has-see-epuc-cun-nau, may-apple, tal-lauhas-see, old town–in the fork of a creek of that name.

- Coo-sau, on the left bank of that river, between the mouths of Eufaule and Nauche (creeks now called Talladega and Kiamulgee).

- Au-be-cho-che, on Nauche creek, five miles from the Coosa.

- Nau-che, on same creek, five miles above the latter.

- Eu-fau-lau-hat-che, fifteen miles still higher up on the same creek.

- Woc-co-coie-woc-co, blow horn, coie, a nest–on Tote-paufcau creek.

- Hill-au-bee, on col-luffa-creek, which joins Hillaubee creek on the right side, one mile below the town

- Thla-noo-che-au-bau-lau-thlen-ne, mountain, ooche, little, au-bau-lau, over–on a branch of the Hillaubee.

- Au-net-te-chap-co-au-net-te, swamp, chap-co, long–on a branch of the Hillaubee.

- E-chuse-is-li-gau, where a young thing was found (a child was found here)–left side of Hillaubee creek.

- Oak-tau-hau-zau-see-oak-tau-hau, sand, zau-see, great dea –on a creek of that name, a branch of the Hillaubee. (1778)

- Oc-fus-kee-oc, in, fus-kee, a point, right bank of the Tallapoosa.

- New-yau-cau, named after New York, when Gen. McGillivray returned from there in 1790, twenty miles above the latter, on the left side of the Tallapoosa.

- Took-au-batche-tal-lau-has-se, four miles above the latter, right side of the river.

- Im-mook-fau, a gorget made of a conch, on the creek of that name.

- Too-to-cau-gee-too-to, corn-house, cau-gee, standing–twenty miles above New-yau-cau, right bank of the Tallapoosa.

- Au-che-nau-ul-gau-auche-nau, cedar, ul-gau, all forty miles above New-yau-cau, on a creek. It is the farthest north of all the Creek settlements

- E-pe-sau-gee, on a large creek of that name.

- Sooc-he-ah-sooc-cau, hog, he-ah, her–right bank of the Tallapoosa, twelve miles above Oc-fus-kee. (1798 )

- Eu-fau-lau, five miles above Oc-fus-kee, right bank of the river.

- Ki-a-li-jee, on the creek of that name, which joins the Tallapoosa on the right side.

- Au-che-nau-hat-che-au-che, cedar, hat-che, creek.

- Hat-che-chub-bau-hat-che, creek, chub-bau, middle or half way.

- Sou-go-hat-chc sou-go, cymbal (musical instrument), hatche, creek–joins the Tallapoosa on the left side.

- Thlot-lo-gul-gau-thlot-lo, fish, gul-gau, all–called by traders “Fish Ponds,” on a creek, a branch of the Ul-hau-hat-che.

- O-pil-thluc-co-o-pil-lo-wau, swamp, thlucco, big–twenty miles from the Coosa, a creek of that name.

- Pin-e-hoo-te-pin-e-wau, turkey, choo-te, house–a branch of the E-pee-sau-gee.

- Po-chuse-hat-che po-chu-so-wau, hatchet, hat-che, creek– (in Coosa county).

- Oc-fus-coo-che, little ocfuskee, four miles above New-yaucaw.

Towns Among the Lower Creeks

- Chat-to-ho-che-chat-to, a stone, ho-che, marked or flowered. Such rocks are found in the bed of that river above Ho-ith-le-tegau. This is the origin and meaning of the name of that beautiful river.

- Cow-e-tough, on the right bank of the Chat-to-ho-che, three miles below the falls.

- O-cow-ocuh-hat-che, falls creek, on the right side of the river at the termination of the falls.

- Hatche-canane, crooked creek.

- Woc-coo-che, calf creek.

- O-sun-nup-pau, moss creek.

- Hat-che-thlucco, big creek.

- Cow-e-tuh Tal-hau-has-se–Cowetuh Tal-lo-fau, a town, hasse, old –three miles 1798 below Cowetuh, on the right bank of the Chattahoochie.

- We-tum-cau–we-wau, water, tum-cau, rumbling–a main branch of the Uchee creek.

Cus-se-tuh, five miles below Cow-e-tuh, on the left bank of the Chattahoochie. - Au-put-tau-e, a village of Cussetuh, on Hat-che-thluc-co, twenty miles from the river.

- U-chee, on the right bank of the Chat-to-ho-che, ten miles below Cowetuh Tallauhassee, and just below the mouth of the Uchee creek.

- In-tuch-cul-gau–in-tuch-ke, dam across water–ul-gau, all; a Uchee village, on Opil-thlacco, twenty-eight miles from its junction with the Flint river.

- Pad-gee-li-gau–pad-jee, a pigeon li-gau, sit, pigeon roost –on the right bank of Flint river (a Uchee village).

- Toc-co-qul-egau, tadpole, on Kit-cho-foone creek (a Uchee village).

- Oose-oo-chee, two miles below Uchee, on the right bank of the Chattahoochie.

- Che-au-hau, below and adjoining the latter.

- Au-muc-cul-le, pour upon me, on a creek of that name, which joins on the right side of the Flint.

- O-tel-who-yau-nau, hurricane town, on the right bank of the Flint.

- Hit-che-tee, on the left bank of the Chattahoochie, one mile below Che-au-hau.

- Che-au-hoo-chee, Little Cheauhaw, one mile and a half west from Hit-che-tee.

- Hit-che-too-che, Little Hitchetee, on both sides of the Flint. Tut-tal-lo-see, fowl, on a creek of that name.

- Pala-chooc-le, on the right bank of the Chattahoochie.

- O-co-nee, six miles below the latter, on the left bank of the Chattahoochie.

- Sou-woo-ge-lo, six miles below Oconee, on the right bank.

- Sou-woog-e-loo-che, four miles below Oconee, on the left bank of the Chattahoochie.

- Eu-fau-la, fifteen miles below the latter, on the left bank of the same river. From this town settlements extended occasionally to the mouth of the Flint. 23

Citations:

- Bartram’s Travels, pp 482, 500, 506.[

]

- Milfort, pp 216-217.[

]

- Bartram’s Travels, pp. 482-506.[

]

- Adair’s American Indians, p. 389[

]

- Bartram’s Travels, pp. 482-506.[

]

- The “Narrative of a Mission to the Creek Nation,” by Col. Marinus Willett, pp. 108-110. Bartram’s Travels, pp. 482-506.[

]

- Hawkins’ “Sketch of the Creek Country,” pp. 73-74.[

]

- Bartram, pp. 513-514.[

]

- Bartram’s Travels, pp. 461-462.[

]

- Milfort, pp. 206-208.[

]

- Bartram’s Travels, pp. 448-454.[

]

- Barnard Roman’s Florida, p. 102.[

]

- Bartram’s Travels, pp. 448-454. The site of Auttose is now embraced in Macon county, and is a cotton plantation, the property of the Hon. George Goldthwaite, Judge of the Eighth Judicial Circuit. On the morning of the 29th of November 1813, a battle was fought here between the Creeks and the Georgians–the latter commanded by Gen. John Floyd.[

]

- Sketch of the Creek Country in 1798-1799, by Benjamin Hawkins, pp. 68-72.[

]

- Hawkins’ Sketch of the Creek Country, pp. 75-78.[

]

- Adair’s American Indians, p. 97.[

]

- Adair’s American Indians, pp. 15-220.[

]

- Conversations with Abram Mordecai a man of ninety-two years of age, whom I found in Dudleyville, Tallapoosa County, in the fall of 1847. His mind was fresh in the recollection of early incidents. Of him I shall have occasion to speak in another portion of the work.[

]

- Hawkins’, pp. 78-79.[

]

- Called by the modern Creek traders “coal flour.”[

]

- Sejour dans la nation Crëck, par Le Clerc Milfort, pp. 240, 252, 21&, 219.[

]

- Adair, pp. 390-391.[

]

- Hawkins’ “Sketch of the Creek Country in 1798-99,” pp. 26-66. In addition to the published copy of this interesting pamphlet, sent to me by I. K. Teffit, Esq., of Savannah, the Hon. F. W. Pickens, of South Carolina, loaned me a manuscript copy of the same work, written by Col. Hawkins for his Grandfather, Gen. Andrew Pickens who was an intimate friend of Hawkins and was associated with him in several important Indian treaties, and whose name will often be mentioned hereafter.[

]