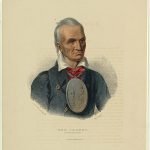

Sa-go-you-rvat-ha, or Keeper awake

1756 – 1830

1 The Seneca tribe was the most important of the celebrated confederacy, known in the early history of the American colonies, as the Iroquois, or Five Nations. They were a powerful and warlike people, and acquired a great ascendancy over the surrounding tribes, as well by their prowess, as by the systematic skill with which their affairs seem to have been conducted. Their hunting-grounds, and principal residence, were in the fertile lands, now embraced in the western limits of the State of New York a country whose prolific soil, and majestic forests, whose limpid streams, and chain of picturesque lakes, and whose vicinity to the shores of Erie and Ontario, must have rendered it, in its savage state, the paradise of the native hunter. Surrounded by all that could render the wilderness attractive, by the greatest luxuriance of nature, and by the most pleasing, as well as the most sublime scenery, and inheriting proud recollections of power and conquest, these tribes were among the foremost in resisting the intrusion of the whites, and the most tardy to surrender their independence. Instead of receding before the European race, as its rapidly accumulating population pressed upon their borders, they tenaciously maintained their ground, and when forced to make cessions of territory to the whites, reserved large tracts for their own use, which they continued to occupy. The swelling tide has passed over and settled around them; and a little remnant of that once proud and fierce people, remains broken and dispirited, in the heart of a civilized country, mourning over the ruins of savage grandeur, yet spurning the richer blessings enjoyed by the civilized man and the Christian. A few have embraced our religion, and learned our arts; but the greater part have dwindled away under the blasting effects of idleness, intemperance, and superstition.

Red Jacket was the last of the Seneca: there are many left who may boast the aboriginal name and lineage, but with him expired all that had remained of the spirit of the tribe. In the following notice of that eminent man we pursue, chiefly, the narrative furnished us by a distinguished gentleman, whose information on this subject is as authentic, as his ability to do it justice is unquestionable.

That is a truly affecting and highly poetical conception of an American poetess, which traces the memorials of the aborigines of America, in the beautiful nomenclature which they have indelibly impressed on the scenery of our country. Our mountains have become their enduring monuments; and their epitaph is inscribed, in the lucid language of nature, on our majestic rivers.

“Ye say that all have passed away,

The noble race and brave

That their light canoes have vanished

From off the crested wave;

That, ‘mid the forests where they roamed,

There rings no hunter’s shout;

But their name is on your waters,

Ye may not wash it out.

“Ye say their cone-like cabins

That clustered o’er the vale,

Have disappeared as withered leaves

Before the autumn gale;

But their memory liveth on your hills,

Their baptism on your shore;

Your ever rolling rivers speak,

Their dialect of yore.”

These associations are well fitted to excite sentiments of deeper emotion than poetic tenderness, and of more painful and practical effect They stand the landmarks of our broken vows and unatoned oppression; and they not only stare us in the face from every hill and every stream, that bears those expressive names, but they hold up before all nations, and before God, the memorials of our injustice.

There is, or was, an Indian artist, self-taught, who, in a rude but most graphic drawing, exhibited upon canvass the events of a treaty between the white men and an Indian tribe. The scene was laid at the moment of settling the terms of a compact, after the proposals of our government had been weighed, and well nigh rejected by the Indians. The two prominent figures in the front ground, were an Indian chief, attired in his peculiar costume, standing in a hesitating posture, with a hand half extended towards a scroll hanging partly unrolled from the hand of the other figure. The latter was* an American officer in full dress, offering with one hand the unsigned treaty to the reluctant savage, while with the other he presents a musket and bayonet to- his breast. This picture was exhibited some years ago near Lewistown, New York, as the production of a man of the Tuscarora tribe, named Cusick. It was an affecting appeal from the Indian to the white man; for although, in point of fact, the Indians have never been compelled, by direct force, to part with their lands, yet we have triumphed over them by our superior power and intelligence, and there is a moral truth in the picture, which represents the savage as yielding from fear that which his judgment and his attachments would have withheld.

We do not design to intimate that our colonial and national trans actions with the Indians have been uniformly, or even habitually unjust. On the contrary, the treaties of Penn, and of Washington, and some of those of the Puritans, to name no others, are honorable to those who presided at their structure and execution; and teach us how important it is to be just and magnanimous in public, as well as in personal acts. Nor do we at all believe that migrating tribes, small in number, and of very unsettled habits of life, have any right to appropriate to themselves, as hunting-grounds and battle-fields, those large domains which God designed to be re claimed from the wilderness, and which, under the culture of civilized man, are adapted to sustain millions of human beings, and to be made subservient to the noblest purposes of human thought and industry. Nor can we in justice charge, exclusively, upon the white population, the corrupting influence of their intercourse with the Indian tribes. There is to be presupposed no little vice and bad propensity on the part of the savages, evinced in the facility with which they became the willing captives, and ultimate victims of that “knowledge of evil,” which our people have imparted to them. The treachery also of the Indian tribes, on our defenseless frontiers, their un-tamable ferocity, their brutal mode of warfare, and their systematic indulgence of the principle of revenge, have too often assumed the most terrific forms of wickedness and destruction towards our confiding emigrants. It is difficult to decide between parties thus placed in positions of antagonism, involving a long series of mutual aggressions, inexcusable on either side, upon any exact principle of rectitude, yet palliated on both by counter balancing provocation. So far as our government has been concerned, the system of intercourse with the Indians has been founded in benevolence, and marked by a forbearing temper; but that policy has been thwarted by individual avarice, and perverted by unfaithful or injudicious administration. After all, however, the burden of guilt must be conceded to lie upon the party having all the ad vantages of power, civilization and Christianity, whose position placed them in the paternal relation towards these scattered children of the forest. All the controlling interests of the tribes tended to instill in them sentiments of fear, of dependence, of peace, and even of friendship, towards their more powerful neighbors; and it has chiefly been when we have chafed them to madness by incessant and unnecessary encroachment, and by unjust treaties, or when they have been seduced from their fidelity by the enemies of our country, that they have been so unwise as to provoke our resentment by open hostility. These wars have uniformly terminated in new demands on our part, in ever-growing accessions from their continually diminishing soil, until the small reservations, which they have been permitted to retain in the bosom of our territory, are scarcely large enough to support the living, or hide the dead, of these miserable remnants of once powerful tribes.

It is not our purpose, however, to argue the grave questions growing out of our relations with this interesting race; but only to make that brief reference to them, which seems unavoidably connected with the biographical sketch we are about to give, of a chief who was uniformly, through life, the able advocate of the rights of his tribe, and the fearless opposer of all encroachment one who was not awed by the white man’s power, nor seduced by his professions of friendship.

From the best information we can obtain, it appears probable, that this celebrated chief was born about A. D. 1756, at the place formerly called ” Old Castle,” now embraced in the town of Seneca, Ontario County, in the State of New York, and three miles west of the present beautiful village of Geneva. His Indian name was Sa~ go-you-rvat-ha, or Keeper awake, which, with the usual appropriateness of the native nomenclature, indicates the vigilance of his character. He acquired the more familiar name, which he bore through life among white men, in the following manner. During the war of the revolution, the Seneca tribe fought under the British standard. Though he had scarcely reached the years of manhood, ho engaged in the war, was much distinguished by his activity and intelligence, and attracted the attention of the British officers. One of them presented him with a richly embroidered scarlet jacket, which he took great pride in wearing. When this was worn out, he was presented with another; and he continued to wear this peculiar dress until it became a mark of distinction, and gave him the name by which he was afterwards best known. As lately as the treaty of 1794, Captain Parish, to whose kindness we are indebted for some of these details, presented him with another red jacket, to perpetuate a name to which he was so much attached.

When but seventeen years old, the abilities of Red Jacket, especially his activity in the chase, and his remarkably tenacious memory, attracted the esteem and admiration of his tribe; and he was frequently employed during the war of the revolution, as a runner, to carry dispatches. In that contest he took little or no part as a warrior; and it would appear that, like his celebrated predecessors in rhetorical fame, Demosthenes and Cicero, he better understood now to rouse his countrymen to war, than to lead them to victory. The warlike chief, Corn Plant, boldly charged him with want of courage, and his conduct on one occasion at least seems to have fully justified the charge. During the expedition of the American General Sullivan against the Indians in 1779, a stand was attempted to be made against him by Corn Plant, on the beach of the Canandaigua lake. On the approach of the American army, a small number of the Indians, among whom was Red Jacket, began to retreat. Corn Plant exerted himself to rally them. He threw himself before Red Jacket, and endeavored to prevail on him to fight, in vain; when the indignant chief, turning to the young wife of the recreant warrior, exclaimed, “leave that man, he is a coward.”

There is no small evidence of the transcendent abilities of this distinguished individual, to be found in the fact of his rising into the highest rank among his people, though believed by them to be destitute of the virtue which they hold in the greatest estimation.

The savage admires those qualities which are peculiar to his mode of life, and are most practically useful in the vicissitudes to which it is incident. Courage, strength, swiftness, and cunning, are indispensably necessary in the constantly recurring scenes of the battle and the chase; while the most patient fortitude is required in the endurance of the pain, hunger, and exposure to all extremes of climate, to which the Indian is continually subjected. Ignorant and uncultivated, they have few intellectual wants or endowments, and place but little value upon any display of genius, which is not combined with the art of the warrior. To this rule, eloquence forms an exception. Where there is arty government, however rude, there must be occasional assemblies of the people; where war and peace are made, the chiefs of the contending parties will meet in council; and on such occasions the sagacious counselor, and able orator, will rise above him whose powers are merely physical. But under any circumstances, courage is so essential, in a barbarous community, where battle and violence are continually occurring, where the right of the strongest is the paramount law, and where life itself must be supported by its exposure in procuring the means of subsistence, that we can scarcely imagine how a coward can be respected among savages, or how an individual without courage can rise to superior sway among such fierce spirits.

But though not distinguished as a warrior, it seems that Red Jacket was not destitute of bravery; for on a subsequent occasion, the stain affixed upon his character, on the occasion alluded to, was wiped away by his good conduct in the field. The true causes, however, of his great influence in his tribe, were his transcendent talents, and the circumstances under which he lived. In times of public calamity the abilities of great men are appreciated, and called into action. Red Jacket came upon the theater of active life, when the power of his tribe had declined, and its extinction was threatened. The white man -was advancing upon them with gigantio strides. The red warrior had appealed, ineffectually, to arms; his cunning had been foiled, and his strength overpowered; his foes, superior in prowess, were countless in number; and he had thrown down the tomahawk in despair. It was then that Red Jacket stood forward as a patriot, defending his nation with fearless eloquence, and denouncing its enemies in strains of fierce invective, or bitter sarcasm. He became their counselor, their negotiator, and their orator. Whatever may have been his conduct in the field, he now evinced a moral courage, as cool and sagacious as it was undaunted, and which showed a mind of too high an order to be influenced by the base sentiment of fear. The relations of the Seneca with the American people, introduced questions of a new and highly interesting character, having reference to the purchase of their lands, and the introduction of Christianity and the arts. The Indians were asked not only to sell their country, but to embrace a new religion, to change their occupations and domestic habits, and to adopt a novel system of thought and action. Strange as these propositions must have seemed in themselves, they were rendered the more unpalatable when dictated by the stronger party, and accompanied by occasional acts of oppression.

It was at this crisis that Red Jacket stood forward, the intrepid defender of his country, its customs, and its religion, and the unwavering opponent of all innovation. He yielded nothing to per suasion, to bribery, or to menace, and never, to his last hour, remitted his exertions in what he considered the noblest purpose of his life.

An intelligent gentleman, who knew this chief intimately, in peace and war, for more than thirty years, speaks of him in the following terms: “Red Jacket was a perfect Indian in every respect in costume, in his contempt of the dress of the white men, in his hatred and opposition to the missionaries, and in his attachment to, and veneration for, the ancient customs and traditions of his tribe. He had a contempt for the English language, and disdained to use any other than his own. He was the finest specimen of the Indian character I ever knew, and sustained it with more dignity than any other chief. He was the second in authority in his tribe. As an orator he was unequaled by any Indian I ever saw. His language was beautiful and figurative, as the Indian language always is, and delivered with the greatest ease and fluency. His gesticulation was easy, graceful, and natural. His voice was distinct and clear, and he always spoke with great animation. His memory was very strong. I have acted as interpreter to most of his speeches, to which no translation could do adequate justice.”

Another gentleman, who had much official and personal inter course with the Seneca orator, writes thus: “You have no doubt been well informed as to the strenuous opposition of Red Jacket, to all improvement in the arts of civilized life, and more especially to all innovations upon the religion of the Indians or, as they generally term it, the religion of their fathers. His speeches upon this and other points, which have been published, were obtained through the medium of illiterate interpreters, and present us with nothing more than ragged and disjointed sketches of the originals. In a private conversation between Red Jacket, Colonel Chapin, and myself, in 1824, I asked him why he was so much opposed to the establishment of missionaries among his people. The question seemed to awaken in the sage old chief feelings of surprise, and after a moment’s reflection he replied, with a sarcastic smile, and an emphasis peculiar to himself, ‘Because they do us no good. If they are not useful to the white people, why do they send them among the Indians; if they are useful to the white people, and do them good, why do they not keep them at home? They are surely bad enough to need the labor of every one who can make them better. These men know we do not understand their religion. We cannot read their book; they tell us different stories about what it contains, and we believe they make the book talk to suit themselves. If we had no money, no land, and no country, to be cheated out of, these black coats would not trouble themselves about our good here after. The Great Spirit will not punish for what we do not know. He will do justice to his red children. These black coats talk to the Great Spirit, and ask for light, that we may see as they do, when they are blind themselves, and quarrel about the light which guides them. These things we do not understand, and the light they give us makes the straight and plain path trod by our fathers dark and dreary. The black coats tell us to work and raise corn : they do nothing themselves, and would starve to death if somebody did not feed them. All they do is to pray to the Great Spirit; but that will not make corn or potatoes grow; if it will, why do they beg from us, and from the white people? The red men knew nothing of trouble until it came from the white man; as soon as they crossed the great waters, they wanted our country, and in return have always been ready to learn us how to quarrel about their religion. Red Jacket can never be the friend of such men. The Indians can never be civilized; they are not like white men. If they were raised among the white people, and learned to work, and to read, as they do, it would only make their situation worse. They would be treated no better than Negroes. We are few and weak, but may for a long time be happy, if we hold fast to our country and the religion of our fathers.’

It is much to be regretted that a more detailed account of this great man cannot be given. The nature of his life and attachments, threw his history out of the view, and beyond the reach of white men. It was part of his national policy to have as little inter course as possible with civilized persons, and he met our country men only amid the intrigues and excitement of treaties, or in the degradation of that vice of civilized society, which makes white men savages, and savages brutes. Enough, however, has been preserved to show that he was an extraordinary man.

Perhaps the most remarkable attribute of his character was commanding eloquence. A notable illustration of the power of his eloquence was given at a council, held at Buffalo Creek, in New York. Corn Plant, who was at that period chief of the Seneca, was mainly instrumental in making the treaty of Fort Stanwix, in 1784. His agency in this affair operated unfavorably upon his character, and weakened his influence with his tribe. Perceiving that Red Jacket was availing himself of his loss of popularity, he resolved on counteracting him. To do this effectually, he Ordained one of his brothers a prophet, and set him to work to pow-wow against his rival, and his followers. The plan consummated, Red Jacket was assailed in the midst of the tribe, by all those arts that are known to be so powerful over the superstition of the Indian. The council was full and was, no doubt, convened mainly for this object. Of this occurrence De Witt Clinton says ” At this crisis, Red Jacket well knew that the future color of his life depended upon the powers of his mind. He spoke in his defense for near three hours the iron brow of superstition relented under the magic of his eloquence. He declared the Prophet an impostor, and a cheat he prevailed the Indians divided, and a small majority appeared in his favor. Perhaps the annals of history cannot furnish a more conspicuous instance of the power and triumph of oratory in a barbarous nation, devoted to superstition, and looking up to the accuser as a delegated minister of the Almighty.” Of the power which he exerted over the minds of those who heard him, it has been justly remarked, that no one ignorant of the dialect in which he spoke can adequately judge. He wisely, as well as proudly, chose to speak through an interpreter, who was often an illiterate person, or sometimes an Indian, who could hardly be expected to do that justice to the orator of the forest, which the learned are scarcely able to render to each other. Especially, would such reporters fail to catch even the spirit of an animated harangue, as it fell rich and fervid from the lips of an injured patriot, standing amid the ruins of his little state, rebuking on the one. hand his degenerate tribe, and on the other repelling the encroachments of an absorbing power. The speeches which have been reported as his, are, for the most part, miserable failures, either made up for the occasion in the prosecution of some mercenary, or sinister purpose, or unfaithfully rendered into puerile periods by an ignorant native.

There are several interesting anecdotes of Red Jacket, which should be preserved as illustrations of the peculiar points of his character and opinions, as well as of his ready eloquence. We shall relate a few which are undoubtedly authentic.

In a council which was held with the Seneca by Governor Tompkins of New York, a contest arose between that gentleman and Red Jacket, as to a fact, connected with a treaty of many years’ standing. The American agent stated one thing, the Indian chief corrected him, and insisted that the reverse of his assertion was true. But, it was rejoined, “you have forgotten we have it written down on paper.” “The paper then tells a lie,” was the confident answer; “I have it written here,” continued the chief, placing his hand with great dignity upon his brow. “You Yankees are born with a feather between your fingers; but your paper does not speak the truth. The Indian keeps his knowledge here this is the book the Great Spirit gave us it does not lie!” A reference was immediately made to the treaty in question, when, to the astonishment of all present, and to the triumph of the tawny statesman, the document confirmed every word he had uttered.

See Further: Red Jacket and the French Nobleman

Citations:

- The portrait represents him in a blue coat. He wore this coat when he sat to King, of Washington. He rarely dressed himself otherwise than in the costume of his tribe. He made an exception on this occasion.[↩]

Discover more from Access Genealogy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.