The Pitchlynn Choctaw family, although represented by one of the smallest name lists in this study, has a long and noted history in the literature of the Old Southwest and Indian Territory (see Chart 18). The eldest Pitchlynn, Isaac, was still alive in 1804 although in ill health. His son, John Pitchlynn, Jr., is recorded as the Choctaw interpreter at the Treaty of Hopewell in 1786 and for nearly half a century was a respected and honored countryman in Choctaw country. John lived a long while on Old Woman’s Creek, a tributary of the Oknoxabee (or Noxobee) River which itself flows into the Tombigbee. John and his family eventually resettled in present-day Lowndes County, Mississippi, near the modern city of Columbus. There the Alabama pioneer Gideon Lincecum met him in 1818 after the Treaty of the Choctaw Trading House in 1816 had opened some lands on the eastern banks of the Tombigbee to white settlers. Interestingly, Lincecum was a distant relative of John Pitchlynn and for a while was in business with his intemperate son, Jack Pitchlynn. Lincecum recalled that:

“As soon as I got my house done, I went over the [Tombigbee] river to see the Choctaws. They were not exceeding two miles distant. I also found there a white man by the name of John Pitchlynn. He had a large family of half breed children; was very wealthy; sixty-two years of age; possessed a high order of intelligence and was from every point of view, a clever gentleman. He was very glad to hear that we were settling so near to him, and he also said he must visit the place we had selected to see if we were building above the high water mark.

“He asked my name, and when I told him, he inquired for the name of my father. I replied, ‘It is Hezekiah Lincecum, “Don’t they call him Ky?’ said he. ‘His familiar friends do, ‘ I replied.’ I am a second cousin to your mother,’ said he. ‘I will go right over and see them this day.’ He was in perfect ecstasy. He ordered his horse, and then turning to me said, ‘You were not born when I saw your father and mother last. I was on my return from Washington city. I had previously heard from my father, that I had relatives in Georgia; and turning my course down through that state, I was lucky enough to find them. I sojourned with them a month, and I look upon that time even now, as the most pleasant period of my life.’

“He went immediately over. I introduced him to my father and mother, and they were overjoyed at meeting again. Twenty-five years had passed and they were all still healthy looking, and exceedingly rejoiced. Pitchlynn was a kind hearted man, and seemed willing to aid us every way he could in making our new homes. We lived neighbors to him from 1818 to 1835; and he continued theme kind hearted gentleman all the time.” 1

Key to Chart

Probable = P, Countryman = C, Yes = Y, Trader = T,

Married = md, Mixed Blood = mb

Chart 18[96a]

https://accessgenealogy.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/174-Pitchlynn-List-of-Mixed-Bloods-2016-10-06.csv is an Invalid Spreadsheet file.

Cushman corroborated Lincecum’s appraisal of Pitchlynn, calling him “a white man of sterling integrity, who acted for many years as interpreter to the Choctaws….” 2 Discussing Pitchlynn’s family, Cushman stated:

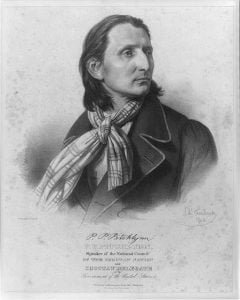

“Colonel John Pitchlynn was adopted in early manhood by the Choctaws, and marrying among them, he at once became as one of their people; and was named by them ‘Chatah It-ti-ka-na,’ The Choctaws friend; and long and well he proved himself worthy the title conferred upon, and the trust confided in him. He had five sons by his Choctaw wife, Peter, Silas, Thomas, Jack and James, all of whom proved to be men of talent, and exerted a moral influence upon their people, except Jack, who was ruined by the white man’s whiskey and his demoralizing examples and influences. I was personally acquainted with Peter, Silas and Jack. The former held, during a long and useful life, the highest position in the political history of his Nation, well deserving the title given by the whites, ‘The Calhoun of the Choctaws’….” 3

Cushman further elaborated on John Pitchlynn:

“He was contemporaneous with the three Folsoms, Nathaniel, Adam and Edwin; the two Le Flores, Louis and Mitchel [Michael], and Louis Durant…. He was commissioned by Washington, as United States interpreter for the Choctaws in 1786, in which capacity he served them long and faithfully. Whether he ever attained the position of chief of the Choctaws is not now known. He, however, secured and held to the day of his death not only the respect, esteem and confidence of the Choctaws as a moral and good citizen, but also that of the missionaries who regarded him as one among their best friends and assistants in their arduous labors….He married Sophia Folsom, the daughter and only child of Ebeneezer Folsom.” 4

His son, Peter, became one of the most influential men of the nation and played a large roll in Choctaw politics following the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. Peter married “Rhoda Folsom, a half-blood daughter of Nathaniel and a half-sister [or cousin] of his mother,” and moved to a site on the edge of a prairie near Mayhew Mission. 5

The Pitchlynn family played a distinctive and critical role as intermediaries between the emerging United States government and the tribal leadership of the Choctaw Nation. John Pitchlynn was an outspoken pro-American who declaimed some of his neighbors as “Torryfied refugees that fled to this nation….” 6

Much has been written of the Pitchlynn family’s contribution to friendship and peace between the two peoples prior to Indian removal, and most of it is richly deserved. John Pitchlynn, recognized as an interpreter during Washington’s presidential terms, had his position reaffirmed by the Jeffersonian administration in the early nineteenth century. The family advised and cooperated with Andrew Jackson’s campaign on the Creek Red Sticks and facilitated more than one major treaty between the United States and the Choctaw Nation.

This continual cooperation between the Pitchlynn family and the first seven presidents of the United States illustrates the long span of a unified federal policy with the tribe as well as the pivotal role played by mixed bloods implementation of that policy. The combination of a Jeffersonian stress on “civilizing” the Indians at a time when the mixed-blood children of Choctaw countrymen were growing in number and influence within the tribe was nearly a perfect marriage of ideology and opportunity. It is also quite probable that future research will disclose numerous other mixed-blood families which impacted for sustained periods on the advent of removal.

As Jefferson postulated the peaceful solution of the “Indian problem,” a growing mixed-blood population eager for the tools of technology was emerging in the Choctaw nation. These mixed bloods in many cases espoused the republican sentiments of their frontiersmen fathers and often sought the blessings of “civilization” even before it was thrust upon them. Along with their appetite for modern tools, the mixed bloods also shared with the Jeffersonian an awareness of the economic impediment to trade caused by Spain’s closure of the rivers flowing from Indian country through West Florida to the Gulf of Mexico. In an interesting parallel to the “Mississippi question” faced by the yeoman farmers of the Ohio valley, the mixed bloods of the Choctaw tribe realized that friendly control of outlets to the sea was an economic necessity and often cooperated with the Jeffersonian government. Indeed, this interaction between[101] the Jeffersonian and the mixed bloods would lead to major changes and social upheaval which would help pave the way to removal.

Citations:

- Linceum, “The Autobiography of Gideon Lincecum,” 472.[

]

- Cushman, History, 242.[

]

- Ibid., 242-3.[

]

- Ibid., 332-3.[

]

- Baird, Peter Pitchlynn, 22. Mayhew Mission was located near present-day Mayhew, Mississippi, between Starkville and Columbus.[

]

- Samuel J. Wells, “Rum, Skins, and Powder: A Choctaw Interpreter and the Treaty of Mount Dexter,” Chronicles of Oklahoma, 61 (Winter 1983-4)4:425; Pitchlynn to Dinsmoor, January 27, 1805, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, RC.2, v24, f7; see also Henry Sales Halbert, “Bernard Roman’s Map of 1772,” Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society, 6 (1902), 439.[

]