Cherokee Indians, Cheroquois tribe. A powerful detached tribe of the Iroquoian family, formerly holding the whole mountain region of the south Alleghenies, in southwest Virginia, western North Carolina and South Carolina, north Georgia, east Tennessee, and northeast Alabama, and claiming even to the Ohio River.

The Cherokee have long held that their tribal name is a corruption of Tsálăgĭ or Tsărăgĭ, the name by which they commonly called themselves, and which may be derived from the Choctaw chiluk-ki ‘cave people’, in allusion to the numerous caves in their mountain country. They sometimes also called themselves Ani´-Yûñ´-wiyá, ‘real people,’ or Ani´-Kĭtu´hwagĭ, ‘people of Kituhwa,’ one of their most important ancient settlements. Their northern kinsmen, the Iroquois, called them Oyata’ge‘ronoñ, ‘inhabitants of the cave country’ (Hewitt), and the Delawares and connected tribes called them Kittuwa, from the settlement already noted. They seem to be identical with the Rickohockans, who invaded central Virginia in 1658, and with the ancient Talligewi, of Delaware tradition, who were represented to have been driven southward from the upper Ohio River region by the combined forces of the Iroquois and Delawares.

Cherokee Language

The language has three principal dialects:

- Elatĭ, or Lower, spoken on the heads of Savannah River, in South Carolina and Georgia;

- Middle, spoken chiefly on the waters of Tuckasegee River, in western North Carolina, and now the prevailing dialect on the East Cherokee reservation;

- A´tăli, Mountain or Upper, spoken throughout most of upper Georgia, east Tennessee, and extreme western North Carolina. The lower dialect was the only one which had the r sound, and is now extinct. The upper dialect is that which has been exclusively used in the native literature of the tribe.

Cherokee Tribe History

Traditional, linguistic, and archeological evidence shows that the Cherokee originated in the north, but they were found in possession of the south Allegheny region when first encountered by De Soto in 1540. Their relations with the Carolina colonies began 150 years later. In 1736 the Jesuit (?) Priber started the first mission among them, and attempted to organize their government on a civilized basis. In 1759, under the leadership of A´ganstâ´ta (Oconostota), they began war with the English of Carolina. In the Revolution they took sides against the Americans, and continued the struggle almost without interval until 1794. During this period parties of the Cherokee pushed down Tennessee River and formed new settlements at Chickamauga and other points about the Tennessee-Alabama line. Shortly after 1800, missionary and educational work was established among them, and in 1820 they adopted a regular form of government modeled on that of the United States. In the meantime large numbers of the more conservative Cherokee, wearied by the encroachments of the whites, had crossed the Mississippi and made new homes in the wilderness in what is now Arkansas. A year or two later Sequoya, a mixed-blood, invented the alphabet, which at once raised them to the rank of a literary people.

At the height of their prosperity gold was discovered near the present Dahlonega, Georgia, within the limits of the Cherokee Nation, and at once a powerful agitation was begun for the removal of the Indians. After years of hopeless struggle under the leadership of their great chief, John Ross, they were compelled to submit to the inevitable, and by the treaty of New Echota, Dec. 29, 1835, the Cherokee sold their entire remaining territory and agreed to remove beyond the Mississippi to a country there to be set apart for them-the present (1890) Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory. The removal was accomplished in the winter of 1838-39, after considerable hardship and the loss of nearly one-fourth of their number, the unwilling Indians being driven out by military force and making the long journey on foot 1. On reaching their destination they reorganized their national government, with their capital at Tahlequah, admitting to equal privileges the earlier emigrants, known as “old settlers.” A part of the Arkansas Cherokee had previously gone down into Texas, where they had obtained a grant of land in the east part of the state from the Mexican government. The later Texan revolutionists refused to recognize their rights, and in spite of the efforts of Gen. Sam Houston, who defended the Indian claim, a conflict was precipitated, resulting, in 1839, in the killing of the Cherokee chief, Bowl, with a large number of his men, by the Texan troops, and the expulsion of the Cherokee from Texas.

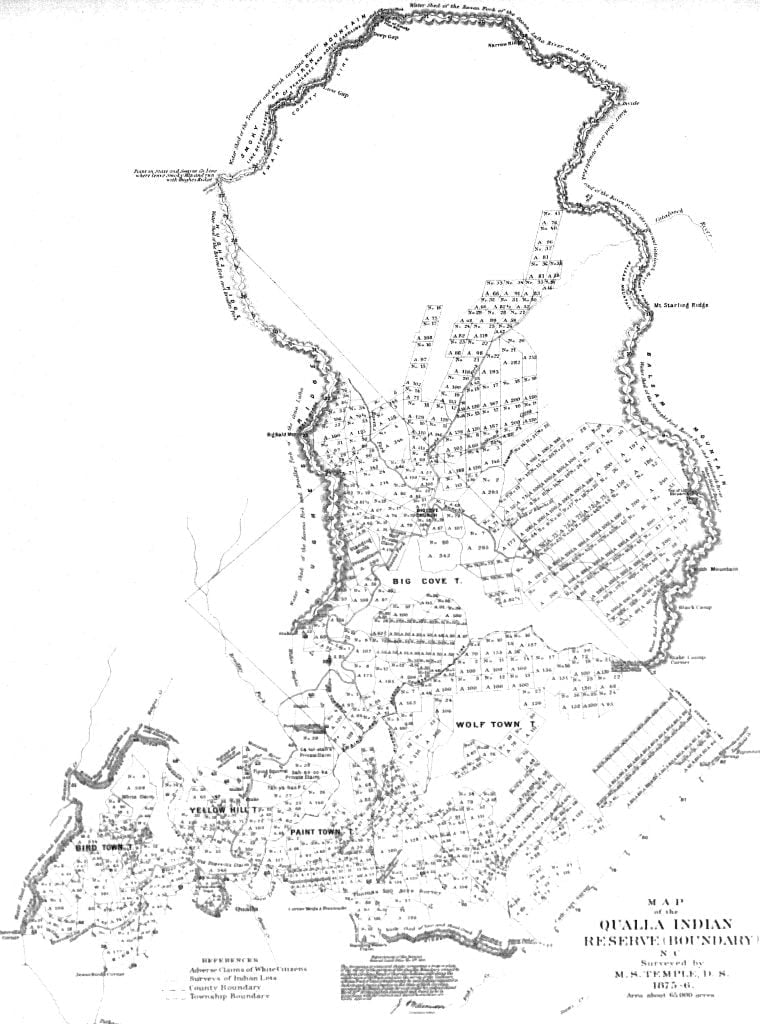

When the main body of the tribe was removed to the west, several hundred fugitives escaped to the mountains, where they lived as refugees for a time, until, in 1842, through the efforts of William H. Thomas, an influential trader, they received permission to remain on lands set apart for their use in western North Carolina.

They constitute the present eastern band of Cherokee, residing chiefly on the Qualla reservation in Swain and Jackson counties, with several outlying settlements.

The Cherokee in the Cherokee Nation were for years divided into two hostile factions, those who had favored and those who had opposed the treaty of removal. Hardly had these differences they been adjusted when the civil war burst upon them. Being slave owners and surrounded by southern influences, a large part of each of the Five Civilized Tribes of the territory enlisted in the service of the Confederacy, while others adhered to the National Government. The territory of the Cherokee was overrun in turn by both armies, and the close of the war found them prostrated. By treaty in 1866 they were readmitted to the protection of the United States, but obliged to liberate their black slaves and admit them to equal citizenship. In 1867 and 1870 the Delawares and Shawnee, respectively, numbering together about 1,750, were admitted from Kansas and incorporated with the Nation. In 1889 a Cherokee Commission was created for the purpose of abolishing the tribal governments and opening the territories to white settlement, with the result that after 15 years of negotiation an agreement was made by which the government of the Cherokee Nation came to a final end Mar. 3, 1906: the Indian lands were divided, and the Cherokee Indians, native adopted, became citizens of the United States.

Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee have 7 clans, viz:

- Ani’-wa’`ya (Wolf)

- Ani’-Kawĭ‘ (Deer)

- Ani’-Tsi’skwa (Bird)

- Ani’-wi’dĭ (Paint)

- Ani’-Sah’a’ni

- Ani’-Ga’tagewĭ

- Ani’-Gi-lâ’hĭ

The names of the last 3 cannot be translated with certainty. There is evidence that there were anciently 14, which by extinction or absorption have been reduced to their present number. The Wolf clan is the largest and most important. The “seven clans” are frequently mentioned in the ritual prayers and even in the printed laws of the tribe. They seem to have had a connection with the “seven mother towns” of the Cherokee, described by Cuming in 1730 as having each a chief, whose office was hereditary in the female line.

The Cherokee are probably about as numerous now (1905) as at any period in their history. With the exception of an estimate in 1730, which placed them at about 20,000, most of those up to a recent period gave them 12,000 or 14,000, and in 1758 they were computed at only 7,500. The majority of the earlier estimates are probably too low, as the Cherokee occupied so extensive a territory that only a part of them came in contact with the whites. In 1708 Gov. Johnson estimated them at 60 villages and “at least 500 men” 2 In 1715 they were officially reported to number 11,210 (Upper, 2,760; Middle, 6,350; Lower, 2,100), including 4,000 warriors, and living in 60 villages (Upper, 19; Middle, 30; Lower, 11). In 1720 were estimated to have been reduced to about 10,000, and again in the same year reported at about 11,500, including about 3,800 warriors 3 In 1729 they were estimated at 20,000, with at least 6,000 warriors and 64 towns and villages 4.

They are said to have lost 1,000 warriors in 1739 from smallpox and rum, and they suffered a steady decrease during their wars with the whites, extending from 1760 until after the close of the Revolution. Those in their original homes had again increased to 16,542 at the time of their forced removal to the west in 1838, but lost nearly one-fourth on the journey, 311 perishing in a steamboat accident on the Mississippi. Those already in the west, before the removal, were estimated at about 6,000. The civil war in 1861-65 again checked their progress, but they recovered from its effects in a remarkably short time, and in 1885 numbered about 19,000, of whom about 17,000 were in Indian Territory, together with about 6,000 adopted whites, blacks, Delawares, and Shawnee, while the remaining 2,000 were still in their ancient homes in the east.

Of this eastern band, 1,376 were on Qualla reservation, in Swain and Jackson Counties, North Carolina; about 300 are on Cheowah River, in Graham County, North Carolina, while the remainder, all of mixed blood, were scattered over east Tennessee, north Georgia, and Alabama. The eastern band lost about 300 by smallpox at the close of the civil war. In 1902 there were officially reported 28,016 persons of Cherokee blood, including all degrees of admixture, in the Cherokee Nation in the Territory, but this includes several thousand individuals formerly repudiated by the tribal courts.

There were also living in the nation about 3,000 adopted black freedmen, more than 2,000 adopted whites, and about 1700 adopted Delaware, Shawnee, and other Indians. The tribe has a larger proportion of white admixture than any other of the Five Civilized Tribes.

For Further Study

The following articles and manuscripts will shed additional light on the Cherokee as both an ethnological study, and as a people.

- Cherokee Indians – Swanton

- Cherokee Treaties

- Treaty of November 28, 1785

- Treaty of July 2, 1791

- Treaty of June 26, 1794

- Treaty of October 2, 1798

- Treaty of October 24, 1804

- Treaty of October 25, 1805

- Treaty of October 27, 1805

- Treaty of January 7, 1806

- Treaty of September 8, 1815

- Treaty of March 22, 1816

- Treaty of September 14, 1816

- Treaty of July 8, 1817

- Treaty of February 27, 1819

- Treaty of May 6, 1828

- Treaty of February 14, 1833

- Agreement of March 14, 1835

- Treaty of August 24, 1835

- Treaty of December 29, 1835

- Treaty of August 6, 1846

- Agreement of September 13, 1865

- Treaty of July 19, 1866

- Treaty of April 27, 1868

- Cherokee Indian Chiefs

- Cherokee Indian Chiefs and Leaders

- Cherokee Indians Location

- Kansas Indian Tribes – Swanton

- Kentucky Indian Tribes – Swanton

- Alabama Indian Tribes – Swanton

- Arkansas Indian Tribes – Swanton

- Georgia Indian Tribes – Swanton

- North Carolina Indian Tribes – Swanton

- South Carolina Indian Tribes – Swanton

- Oklahoma Indian Tribes – Swanton

- Virginia Indian Tribes – Swanton

- West Virginia Indian Tribes – Swanton

- Cherokee Indian Rolls

- Reservation Roll

- Disbursements to Cherokees under the Treaty of May 6, 1828

- Trail of Tears Roll, 1835

- 1835 Henderson Roll

The following is the 1835 Cherokee East of the Mississippi Census or otherwise known as the Henderson Roll. This is only an index of the names. Researchers should consult the full roll in order to get more specific information on each family listed. In 1835, the Cherokee Nation contained almost 22,000 Cherokees and almost 300 Whites connected by marriage. This roll enumerates 16,000 of those people under 5,000 different families. - 1838 Cherokee Muster Roll 1

The muster roll details the arrival of Lt. Deas and a large group of Cherokees to the West on May 1, 1838. - 1838 Cherokee Muster Roll 2

The 1838 muster roll documents the journey of 1,072 Georgia Cherokees from Rosses Landing to Indian Territory, culminating with 635 survivors arriving on September 7, 1838. The official count recorded on July 23 noted 763 individuals, accounting for 144 deaths, 289 desertions, and 2 births along the Trail of Tears. The detailed enumeration lists 91 family groups, suggesting many of the missing were likely enslaved individuals whose descendants later became Cherokee freedmen. - Old Settlers Roll, 1851

- Drennen Roll, 1852

- Act of Congress Roll, 1854

- Hester Roll, 1883

- Index to Final Roll, 1889-1914

- Final Roll, 1889-1914

- Understanding the Final (Dawes) Rolls

- Wallace Roll, 1890 (Cherokee Freedmen)

- Kern Clifton Roll, 1897 (Cherokee Freedmen)

- Guion Miller Roll, 1909 (Eastern Cherokee)

- Baker Roll, 1924 (Eastern Cherokee)

- Enrollment of Five Civilized Tribes, 1896

- Cherokee Indian Bands, Gens and Clans

- 1880 Cherokee Nation Census

- Sacred Formulas of the Cherokee

- Indian Missions of the Southern States

- Oklahoma Indian Tribal Schools

- Cherokee Orphan Asylum

- Legal Status of Indians, 1890

- A Century of Dishonor

- How to Register for your CDIB Card

- Native American Land Patents

- 1828 Abstracts of the Cherokee Phoenix

- Abeel and Allied Families

- An Overland Journey to the West

- Cherokee Nation of Indians

- Cherokee Proposals for Cession of their Land

- History of the Cherokee Indians, Legends and Folklore -Emmet Starr

- The Cherokee of the Smoky Mountains

- Eastern Cherokee of North Carolina

- Native Uprisings Against the Carolinas (1711-17)

- Free US Indian Census Schedules 1885-1940

- Eastern Cherokee Indian Agency

- 1898-1899 Eastern Cherokee Indian Agency Census

- 1904 Eastern Cherokee Indian Agency Census

- 1906 Eastern Cherokee Indian Agency Census

- 1909-1912 Eastern Cherokee Indian Agency Census

- 1914 Eastern Cherokee Indian Agency Census

- 1915-1922 Eastern Cherokee Indian Agency Census

- 1923-1929 Eastern Cherokee Indian Agency Census

- 1930-1932 Eastern Cherokee Indian Agency Census

- 1933-1939 Eastern Cherokee Indian Agency Census

- Eastern Cherokee Indian Agency

Citations:

- See Trail of Tears Roll for a list of those participating in the march[

]

- Rivers, So. Car., 238, 1856.[

]

- Gov. Johnson’s Rep. in Rivers, So. Car., 93, 94, 103, 1874.[

]

- Stevens, History of Georgia, I, 48, 1847[

]