Holland Coffee was a trader operating at Fort Smith with Robert M. French and others, under the name of Coffee, Calville and Company. When Colonel Dodge’s expedition to the Comanche country was being arranged, this firm of traders saw in the plans an opportunity for profitable enterprise, and organized a trading expedition to the western country. Soon after the dragoons took up their march from Fort Gibson, Coffee’s company, forty strong, left Fort Smith on the first of August. Proceeding as far as the Canadian River, they halted and went into camp to await the result of Colonel Dodge’s conference with the western tribes. When it was known that the meeting of the dragoon officers and eastern Indians with the Indians of the prairies was friendly and conciliatory, so that it was safe to proceed, Coffee’s company resumed their march to the west, and upon arrival set up a trading establishment on Red River at what was called the old Pawnee village, about twenty miles above the Cross Timbers and seventy-five miles in a direct line above the mouth of the Washita River. The trading house was on the north bank of Red River, and surrounded by a picket fortification about one hundred feet square. 1

Isaac Pennington was another trader who had been associated with Colonel Chouteau and Colonel Hugh Glenn on the Verdigris. He also went out among the western Indians directly after the conference at Fort Gibson in September. In March 1835, Coffee, Calville, and Pennington came east to the Choctaw Agency, a few miles west of Fort Smith, and called upon Major F. W. Armstrong, Acting Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Western Territory, and then visited Captain Stuart in command at Fort Coffee near by. They informed these officials that the conference of the preceding fall had made a favorable impression on the western tribes who were friendly and peaceable, and inclined to continue so as long as their confidence in the white officers lasted. But these Indians were becoming restless for further assurances of the conference and treaty which Colonel Dodge had allowed them to believe would be held with them in their western country, and which they desired to be near Coffee’s trading establishment. There was some question of Dodge’s authority to give this assurance, but having given it, the western officials realized the importance of keeping faith with the Indians. Within a short time after the visit of these two traders, two Wichita and a Waco Indian came to Fort Gibson, commissioned by their tribes to inquire when the council would be held. On the arrival of these Indians, General Arbuckle 2 had much difficulty in ascertaining their business. As there was no interpreter at the post, General Arbuckle sent to the Osage village for a woman living among them, who was known to be able to speak the language of these Indians; she was away from home in the woods, as the messenger expressed it, and it was some weeks before it was possible to converse with the western Indians.

In the meantime a commission was received from the Secretary of War appointing Governor Stokes, General Arbuckle 3 and Major F. W. Armstrong, 4 commissioners to hold a conference with the Comanche, Kiowa, and other western tribes at Fort Gibson. The object of the treaty and conference, as recited in the letter of instructions, was to establish amicable relations between the Comanche and other predatory tribes roaming along the western border, and the United States; and between these and other Indian tribes.

The Terms of the Conference at Fort Gibson

The board of commissioners organized early in May and having secured an interpreter, discussed with the western emissaries the matter of holding a conference at Fort Gibson. After two days of discussion, the commissioners learned that it would be impossible to secure even an interview with the Comanche and other chiefs until late in July. They were informed that a war party had gone over the line into Texas, and the remaining bands were hunting on the great prairies; and that neither party would return until the green corn raised by the Wichita was ripe enough for eating. Wandering and hunting bands annually visited the Wichita, the farming Indians described by Wheelock in his journal, and procured corn from them. Because of the promise made these Indians by Colonel Dodge, that the council would be held in their country, they would not consider any other arrangement. The commissioners deemed it imprudent to vary from the plans which the western Indians had understood were to be followed, and decided to conform to their views unless they could yet be brought to Fort Gibson by inducements which would not shake their confidence in the white officers. The commissioners therefore decided to send Major Mason, 5 with a party of dragoons, from Fort Gibson to the headwaters of Little River to establish a camp at a suitable place for holding the conference with the western Indians, if their chiefs could not be prevailed upon to come to Fort Gibson. Accordingly, on May 18, Major Mason left Fort Gibson with a detachment of dragoons, and marched about one hundred fifty miles southwest to a point where he would be in touch with Coffee’s trading post on Red River, about seventy miles south. A report had reached Fort Gibson that the Mexicans planned an attack upon the Comanche, and had warned Coffee to abandon his post. Mason’s post, which he located at the edge of the Cross Timbers and called Camp Holmes, was described as a beautiful location, with a border of timber to the east, ten miles of prairie to the west, encircled with sparse woods and having a fine running creek and a number of springs. 6

Deaths of Seaton and Armstrong

On June 16, Lieutenant Seaton of the infantry was dispatched from Fort Gibson with a force of thirty-men, to cut a wagon road through to Major Mason’s position, and to convey provisions for the troops stationed there, and he returned to Fort Gibson on July 19. Excessive rains prevailed during Seaton’s absence from Fort Gibson, and for eleven days he and his men were camped on a ridge surrounded by water near Little River. For nearly a month the men in his command were without dry clothing, and Seaton 7 contracted an illness from which he died at Fort Gibson in the fall.

Near the first of July, the Comanche and other tribes began arriving at Mason’s fort in great numbers, and refused to yield their determination to have the conference in the west. They established themselves in camp eight or ten miles from Camp Holmes in such numbers that one report said there were seven thousand present. Their number was so large and their attitude so menacing, upon viewing the handful of men under Major Mason, that on the third day of July this officer dispatched messengers to General Arbuckle and requested reinforcements. General Arbuckle returned an answer at once by the Osage Indians who brought the message, assuring Major Mason that he should have reinforcements, and directly dispatched to his assistance companies T and H of the Seventh Infantry, numbering one hundred men under Captain Lee, together with a piece of ordnance.

While the commissioners were making their plans to go to Camp Holmes for the conference, Major Armstrong was taken seriously ill, and on the sixth of August he died at his home at the Choctaw Agency. 8 On the same day, General Arbuckle and Governor Stokes departed from Fort Gibson for Camp Holmes, with an escort of companies A and D of the Seventh Infantry, under Major Birch. 9 Accompanying them were delegations from the Creek, Osage, Seneca, and Quapaw; the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Delaware were to follow immediately. On their arrival at Camp Holmes, the force of soldiers amounted to two hundred fifty; this number the commissioners decided necessary to enable them to maintain their position and secure the respect of the Indians, and as a warning to the western tribes that if they refused to enter into the treaty desired by the United States, the latter were able to, and would if they chose, occupy the position permanently.

The commissioners left Fort Gibson at a much later period in the summer than that in which the Dragoons left the year before. The distance traveled was not so great, and it was probably not so hot; for no great number of deaths resulted. Governor Stokes was not well when they left Fort Gibson, and a report came back to the post that he was dying at a camp along the road; but this resolute seventy-five-year-old campaigner not only took part in the conference with the wild prairie Indians, and performed all the labors required by his commission, but intrepidly covered the three hundred miles entailed by the journey through July and August, and returned to Fort Gibson in good health.

Conference at Fort Gibson Begins

After the usual preliminaries and speech making, and with the assurance of presents to be made after the signing, the treaty was finally entered into on August 24, 1835 10 between the Wichita, their associated bands or tribes, and the United States; and between these western Indians and the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Osage, Seneca, and Quapaw. The Kiowa did not remain to participate in the treaty, and in fact left before the commissioners arrived. It was reported that they became impatient with the delay, and departed for their homes; it was also said by officers present that they left through fear of the Osage, instigated by Clermont. The treaty contained assurances of peace and friendship between the contracting parties, and a grant of free passage through the western Indian country for citizens of the United States to Santa Fe and to Mexico; and provided that the eastern Indians might hunt and trap throughout the country west of the Cross Timbers as far as the limits of the United States. Camp Holmes was located within the country granted by treaty to the Creek Indians, whose right to occupy this country had not, up to the time of the treaty, been recognized by the western tribes. After the conference the infantry left Camp Holmes for Fort Gibson, but the dragoons arrived there first, on the fifth of September. Governor Stokes and General Arbuckle reached Fort Gibson on the twelfth.

Thus was enacted the first treaty with the wild western prairie tribes so essential to the plans of the Government for the location of the eastern Indians west of the Mississippi, and necessary to the peace and security of the West and to the traders and pioneers in all that great expanse of country. And thus was consummated what for years the Government was trying to accomplish, with Fort Gibson as the basis of operations, and for which many lives had been sacrificed.

But the object of the Government was not yet fully gained, and it now became a matter of importance to induce the Kiowa Indians to go to Fort Gibson; an enterprise these Indians were reluctant to engage in, because it would entail one hundred miles of travel between the Cross Timbers and Fort Gibson, nearly destitute of buffalo, and they were not yet well enough assured of the candor of the white men to trust a few of their number among them so far from their friends.

“The celebrated Cross Timbers, of which frequent mention has been made, extend from the Brazos, or perhaps from the Colorado of Texas, across the sources of Trinity, traversing Red River above the False Washita, and thence west of north to the Red Fork of Arkansas, if not further. It is a rough hilly range of country, and, though not mountainous, may perhaps be considered a prolongation of that chain of low mountains which pass to the northward of Bexar and Austin City in Texas.

“The Cross Timbers vary in width from five to thirty miles, and entirely cut off the communication betwixt the interior prairies and those of the great plains. They may be considered as the ‘fringe’ of the great prairies, being a continuous brushy strip, composed of various kinds of undergrowth; such as black-jacks, post-oaks, and in some places hickory, elm, etc., intermixed with a very diminutive dwarf oak, called by the hunters ‘shin-oak’. Most of the timber appears to be kept small by the continual inroads of the ‘burning prairies’; for, being killed almost annually, it is constantly replaced by scions of undergrowth; so that it becomes more and more dense every reproduction. In some places, however, the oaks are of considerable size, and able to withstand the conflagrations. The underwood is so matted in many places with grapevines, green-briars, etc., as to form almost impenetrable ‘roughs’, which serve as hiding-places for wild beasts, as well as wild Indians; and would, in savage warfare, prove almost as formidable as the hammocks of Florida.” 11

In early days, traders and trappers employed the Cross Timbers as a datum line for location, and measured distances of places from this well-known landmark, as in populated parts of the world reference is made to the Meridian of Greenwich.

On some of the old maps 12 the Cross Timbers is shown extending up the ninety-eighth meridian, between Red and Canadian rivers which gives it a north and south course through the country embracing Chickasha and El Reno, Oklahoma. On a Government map of 1834 13 a legend is printed up and down this line “Western Boundary of Habitable Land.” In the adjustment of the affairs of the Choctaw and Chickasaw Indians in 1866, this line was taken as the western boundary of the possessions of those tribes and all west of it was ceded to the United States for the use of the prairie tribes of Indians, who at all times claimed that the rights of the emigrant Indians did not extend west of the Cross Timbers. This line so established became part of the dividing line between Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory.

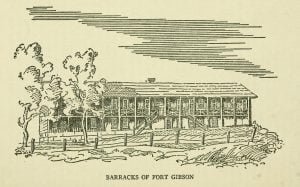

Fort Gibson

After three years of patient labor it was late in 1827 before the fort and other defenses at Cantonment Gibson were completed; the quarters were spacious and comfortable and ample to garrison a regiment. The troops, after three or four years of fatigue duty, began a strict course of drill and discipline. The fort itself was a square three hundred feet on a side, surrounded by a log barricade with blockhouses at the northwest and southeast corners, and contained barracks, store houses, and officers’ quarters. A hospital and several log houses used for quarters were some distance east of the fort and toward the rising ground. One building was erected for an Indian council house. It was called the Theatre and here the soldiers entertained themselves by getting up plays and presenting them. A cemetery, sawmill, stables, and hay-barn were southwest of the fort; two sutlers’ stores were on the bank of the river northeast of the fort. From a ferry across the river a road lay northwest to Creek Agency and the traders’ stores at the falls of the Verdigris. Three miles out on this road Houston established his store.

Cantonment Gibson soon began to assume a place of great importance in the Southwest and was the center of all the civilized life and interest for hundreds of miles around. A lively celebration of the Fourth of July, 1826, serves to illustrate the isolation of the post and its importance as a center of southwestern activity. At the dinner given on this occasion, thirteen toasts were drunk; the formula – “The President of the United States” one gun and three cheers; the number of guns and cheers measured by the subject of the toast. The twelfth toast was “The Festive Board”, four cheers. The thirteenth, “The Fair Sex”, seven cheers. There is something touching in the picture of these men exiled to the wilderness hundreds of miles from friends and relatives, trying to be gay and patriotic. Speeches were made by Captain Pierce M. Butler, Colonel John Nicks, 14 Captain Nathaniel Pryor, John Dillard, Colonel A. P. Chouteau, and others. They were probably well sustained in their efforts at gaiety; fortified by six thousand gallons of good proof whiskey the post should have been well prepared for the demands of any Fourth of July. This consignment of whiskey was one of the established items purchased annually by the War Department for Cantonments Gibson, Towson, and other western posts. Some of the other items for annual consumption at the post were four hundred barrels of pork; eight hundred barrels of flour; three hundred sixty bushels of beans; sixty-six hundred pounds of hard soap; thirty-five hundred pounds of hard tallow candles with wicks; fifteen hundred bushels of salt, and fourteen hundred gallons of vinegar.

Fort Gibson occupied the central position of the five outposts marking our western frontier; from north to south, Forts Snelling, Leavenworth, Gibson, Towson, and Jesup. The position of Fort Gibson in the center was reckoned the most responsible and important, and in 1832 it had ten companies of infantry and three of rangers, nearly as many as the combined forces of the other four posts.

While Fort Gibson was linking up the Southwest with the United States for they were spoken of separately-other news was emanating from that outpost. Fort Gibson of that day was not located on the fine elevation where it was rebuilt during the Civil War and where the village of the same name is now to be seen. For some unknown reason it was located below the hill on the lowland along Grand River, surrounded by a canebrake where the water remained stagnant after rains and bred mosquitoes and deadly malarial germs. The dragoon expedition of 1834 had occasioned wide interest and the press of the country contained frequent accounts of that unprecedented adventure and subsequent conditions and events at the post. The most impressive item of news was that concerned with the fearful death rate of the members of the command. Nearly every issue of the weekly papers and frequent numbers of the dailies, reproduced accounts of Fort Gibson and there was no lack of willing correspondents crying out to the country against conditions under which they were forced to live. One account 15 said:

“I think Fort Gibson the worst, and without doubt the hottest and most unhealthy in the U. States. Besides, our quarters are truly rotting over our heads, and not sufficient by one-fourth to accommodate the third of the officers of the regiment, if present, and none to be built] but patch, patch, patch the old ones up, here and there, to stop a leak.

“This, however, is not the greatest of our troubles or vexations, for almost every day, surely every week, an armed command leaves here either for the prairies, or to seek and destroy whiskey in the Cherokee Nation. Our garrison, as to troops, are reduced to the smallest number from these causes and sickness. Captain L., from necessity, had to command a detachment of two companies that left here last week for the headwaters of the False Washita, and neither was his own. Lieutenant Seaton has another detachment of thirty men escorting provisions to Major Mason, who is encamped on the headwaters of Little River. Major B. commands two companies encamped out on the hills, to scatter the troops on account of the sickness in the garrison, and Lieutenant G. has another detachment of ten men taking villianous white people out of the Indian country, and Lieutenant P. another detachment hunting for whiskey. Such is our constant occupation and duties, harassing to officers and soldiers… God grant that by your influence united you could get the regiment removed; it would meet the approbation of every one in it, except three.” Another wrote in the fall of 1835: 16 “Sickness still prevails at this most infernal of all military posts,… if you were to visit Fort Gibson you would pronounce it the most perfect caricature of a military establishment that was ever seen in any service; it is situated, it may be said with a good deal of truth, in the bottom of a sink hole… These bottoms are low and subject to inundation, and contain several large sloughs and lakes of stagnant water.” Another wrote: “Two hundred dragoons now await the sound of the ‘last bugle’ in its graveyard, a majority of them laid there in less than nine weeks (September and October 1834) besides many of the 7th Infantry and some strangers… On this date (17 October, 1835) out of six officers in the dragoon garrison, four, including the assistant surgeon, are on the sick report and nearly half of the men.”

Resignations and Death at Fort Gibson

Official reports showed that during the two years preceding December 8, 1835, two hundred ninety-two soldiers and six officers had died at the post; from the establishment of the post in 1824 five hundred sixty-one soldiers and nine officers had died. And during the third quarter of the year 1835 there were six hundred and one distinct cases of disease at the post in the infantry alone. It is not surprising that there were a large number of resignations, and that a movement was inaugurated for the removal of the post, which assumed such proportions that in February, 1836, Major-general Macomb recommended the removal of the garrison to Fort Coffee ten or twelve miles above Fort Smith.

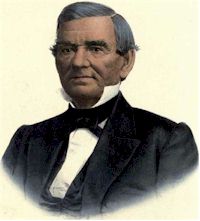

Among those who resigned was Lieutenant Jefferson Davis, whose resignation took effect on June 30, 1835. He went from Fort Gibson to Kentucky, to meet Miss Sarah Knox Taylor, daughter of General Zachary Taylor, to whom he was engaged, and they were married directly afterward. An error has persisted that Davis courted his wife at Fort Gibson while her father was in command there. General Taylor’s daughter never saw Fort Gibson and it was long after her death when General Taylor served at the post.

Lieutenant Jefferson Davis’ Marriage to Miss Sarah Knox Taylor

General Taylor was in command at Fort Crawford, Prairie du Chien, on the upper Mississippi in 1832, and serving under him was young Lieutenant Davis. It was there that Davis and Miss Taylor fell in love and became engaged. Her father was unalterably opposed to the match and said he would never give his consent. After the two young people became engaged, Davis was transferred to the Dragoons with which organization he served at Fort Gibson in 1834; but after two years had passed and her father refused to relent, Miss Taylor, who had inherited some of his determination, took matters into her own hands. A steamboat having arrived at the post she induced her brother-in-law to secure a stateroom for the return passage to Saint Louis. Before the boat started Miss Taylor went again to her father and told him she was determined to marry Davis and was leaving home for that purpose but that she hoped he would consent. He again refused and she sorrowfully gave up hope of winning his approval. Departing from Fort Crawford, Miss Taylor went by boat to Saint Louis and from there to the home of her aunt in Kentucky. In refuting the story of an elopement, Davis once said: 17

“In 1835 I resigned from the army, and Miss Taylor being then in Kentucky with her aunt – the oldest sister of General Taylor – I went thither and we were married in the home of her aunt, in the presence of General Taylor’s two sisters, of his oldest brother, his son-in-law, and many others of the Taylor family.”

The estrangement between Lieutenant Davis and General Taylor was not healed during the lifetime of Mrs. Davis. After their marriage they went to live on a tract of land given to him by his brother in Mississippi, called Brierfield; Davis set to work to clear it up, and he and his wife were both taken sick of malarial fever, from which she died on September 15, 1835.

As soon as they were able to travel after the disastrous dragoon expedition of 1834, several of the companies of dragoons were sent to Fort Leavenworth and Fort Des Moines. Lieutenants T. B. Wheelock and James F. Izard, who had figured so prominently in the dragoon expedition were ordered to Florida in the service against the Seminole Indians, where they were both killed. On February 28, 1836, in a skirmish with the Indians on the Withlacoochee, Izard was wounded, and died on March 5, at Camp Izard. His death was deplored by the members of the dragoon regiment who in their remote stations adopted resolutions setting forth the high regard in which he was held. On the tenth of June, 1836, Lieutenant Wheelock, at the head of a detachment under orders from his chief, Major Heileman, had creditably carried out a sortie against the Indians at Micanopy. His service had been so arduous that he was seized with a fatal aberration in which, five days later, he killed himself with his rifle.

Order Books and Letter Books about Fort Gibson

Much of the life of the frontier post of those days is reflected in the order books and letter books of Fort Gibson. 18 Daily routine orders for the conduct of the post are recorded; when the commanding officer leaves the post an order is made delegating the command to another. Detachments are ordered out of the post in the discharge of the numerous duties required of them. On January 1, 1839, Captain Bonneville is ordered to take his company and start on the long march to Tampa, Florida. John Howard Payne is entertained at the post in October 1840 by Captain George A. McCall. Payne spent that winter at Park Hill as the guest of Chief John Ross.

One of the soldiers is reported a deserter and a small party under a non-commissioned officer is detailed to scour the woods or descend Arkansas River in search of him as he is probably headed for the settlements. Desertions are of frequent occurrence, and the most familiar entries on the books are those ordering a court-martial, and the subsequent proceedings of the court. Punishments were brutal and apparently not deterrent. Sanford Lacy stole a pair of trousers and decamped but he was captured after a week of desertion. He was convicted and sentenced to receive fifty lashes on the bare back with a raw hide well laid on at intervals of forty-eight hours; to be confined at hard labor for six months with a ball and chain and to reimburse the United States for the expense of apprehending him. Private James Laden on sentry duty at post number three on the night of August 14, 1838, was found asleep. The court-martial adjudged him guilty and sentenced him to four months confinement in the post, sixty days in the cells on bread and water, and the remainder at hard labor with ball and chain. Another for habitual drunkenness was sentenced to forfeit his pay, have half his head shaved and be drummed out of the post and service. Drunkenness was common and soldiers frequented disorderly houses kept by Cherokee individuals on the tribal land just outside the reservation where they were beyond the control of the garrison. Drinking and fighting, bloodshed and frequent killings occurred at these places. Some years later, in 1846 authority was given for the sutler to sell liquor to the soldiers under the regulations of the commanding officer, with the result, Colonel Mason reported, that disorderly houses were abandoned and drunkenness was much reduced.

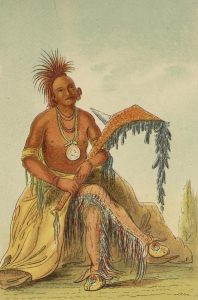

Cherokee Chief

Extended reports are required in connection with the killing by Lieutenant Charles Wickliff, 19 a West Point graduate, of Robert Wilkins who lived near Fort Gibson. Wickliff had an affair with Wilkins’s wife, a half-breed Cherokee and on January 9, 1842, the former shot Wilkins in the back with a double barreled shot gun. Wickliff was arrested but broke arrest and became a deserter. Another lieutenant was court-martialed for being heard to express approval of what Wickliff did. Complaints are recorded by Chief John Ross and other Cherokee that their negro slaves in considerable numbers have fled toward Texas. A number of them settled in the west in a community that became the town of Wewoka. Frequent complaints are received concerning Josiah Hardridge, and Osiah Harjo, Creek Indians, who are engaged in kidnapping free colored people, running them off and selling them into slavery. Several hundred Seminole negroes who surrendered in Florida to General Jesup under promise of emancipation from the slavery by which they were held by the Seminole, are settled around Fort Gibson and are clamoring for the officers of the post to secure them in their freedom.

A feud existed between Colonel Mason in command and Governor Butler, Cherokee agent and the former had an order made requiring the agent to remove from the reservation as his Indian visitors were obnoxious to the officers. An order was made also that the sutlers at the post should not sell to or traffic with the Indians, but it was afterwards relaxed. In July 1844, the Fort Gibson Jockey Club was organized with Governor Butler as president, and races were held near the post on September 24, and through the week, on an old race course laid out many years before by the Seventh Infantry. This was objected to by Colonel Mason. The Cherokee caught some of the colored servants of the officers and horse-whipped them. Two of Captain Boone’s men were murdered on March 12, 1845, at a disorderly house three-fourths of a mile south of the dragoon barracks, kept by Polly Spaniard, a part Cherokee. The next night the soldiers burned her house and one or two others. An anonymous proclamation was then circulated saying that the Cherokee would meet at Tahlequah to consider measures for protecting themselves against the military. Mason charged that this was prepared by Butler.

Colonel Loomis reports December 18, 1843, that the post was in bad police when he took charge and the command has been engaged for some time in white-washing and policing the garrison. Deaths of officers are reported from time to time. July 22, 1844, Captain Boone is reported ill to the point of death, but he recovered and in the fall, reports tell of his expedition to the Indians on the Brazos, his return, and report.

Colonel Mason becomes ill and the wordy controversy as to which of two captains has succeeded to the command, and the records of attempted arrest of each by the other become amusing and consume many pages before Mason leaves his sick bed again to assume command and end the quarrel. Mason reports the building of a house twenty-two by forty feet for a church and school room. The church had formerly been held in the post library room which was too small for a congregation. Numerous reports are received concerning disturbances in the Cherokee Nation where several murders were committed during the election in the fall of 1845. A large number of Cherokee collected at the home of Lewis Ross at Grand Saline and Captain Boone was sent out with his company to maintain order; he remained in camp several months near Evansville, Arkansas.

Entries are made of the movements of troops on numerous missions to the prairies, to Fort Smith, Fort Towson and elsewhere; officers leaving the post and officers returning; reports of visiting Indians of different tribes and traders from near and far who bring accounts of many things – movements of the Indians, of white prisoners among them, of difficulties among the Indians, rumors, small talk. Captain Boone has seen a young Kickapoo chief who is on his way with a small party to see their principal chief on the Missouri River to request him to send a mission to the Pawnee on the Platte to induce the latter to cease their depredations on the Kickapoo living along the Canadian. Measures for removing the Seminole settled around Fort Gibson consume much space. As the Mexican War draws the seasoned troops from Fort Gibson, they are replaced by numerous detachments of volunteers from Arkansas and Kentucky. Soon after their arrival measles broke out among them and many died. Work on the new buildings at Fort Gibson was stopped in 1846 for lack of funds.

Citations:

- Armstrong to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs March 6, 1835 (Indian Office, 1835, Southwestern Territory). Captain Stuart writing from Fort Coffee says, “The trading post is at the extreme west edge of the Cross Timbers on Red River.” (Stuart to Lieutenant W. Seawell, March 28, 1835, Ibid., 1835 Western Superintendency). The trading post was first established in 1834 within what is now the southwest part of Tillman County, Oklahoma.

Col. A. P. Chouteau (Chouteau to Armstrong May 22, 1837, Indian Office, 1837 Western Superintendency A-183) locates Coffee’s trading house at that The trading time on Walnut Bayou, which empties into Red River within what is now Love County, Oklahoma. At approximately this location there was sub-sequently a trading post known as Warren’s, which was abandoned in 1848 and located at the mouth of Cache Creek.[

]

- General Arbuckle had been returned to the command of Fort Gibson after the death of General Leavenworth.[

]

- Secretary of War Cass, to Stokes, Arbuckle, and Armstrong, March 23, 1835; Indian Office, Letter Book no. 15, p. 195.[

]

- Francis W. Armstrong born in Virginia; appointed to the army from Tennessee; captain of the Seventh Infantry with brevet of major from June 26, 1813. He resigned April 30, 1817; served as United States Marshal for the District of Alabama. March 1831, Major Armstrong was appointed agent for the Choctaw in Arkansas Territory and later became Acting Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Western Territory, which office he held until his death.[

]

- Richard Barnes Mason was born in Virginia; major of the Dragoon Regiment March 4, 1833, and for several years saw much service at Fort Gibson. He was made Lieutenant-colonel July 4, 1836, colonel June 30, 1846; brevet-major July 31, 1829, for ten years faithful service in one grade, and Brigadier-general May 30, 1848, for meritorious conduct. In 1848 Colonel Mason was in command of the Tenth Military Department, with headquarters at Monterey, California. He died July 25, 1850.[

]

- “In 1835, shortly after the treaty with the Comanche at Camp Holmes, Colonel Auguste Chouteau built on the same site a small stockade fort, where a considerable trade was carried on with the Comanche, Kiowa, Wichita, and associated tribes until his death three years later, when the place was abandoned. The exact location of Camp Holmes and Chouteau’s fort, was at a spring on a small creek, both still bearing the name of Chouteau, on the east or north side of South (main) Canadian River, about 5 miles northeast of where now is the town of Purcell, Indian Territory. It was a favorite Indian camping ground and was the site of a Kichai village about 1850.”. U.S. Bureau of Ethnology, Seventeenth Annual Report, 1895-1896, part i, 171.[

]

- Augustine Fortunatus Seaton was born in the District of Columbia, from which place he was appointed to West Point, graduated July 1, 1833, and he served with the Seventh Infantry at Fort Coffee and Fort Gibson until his death November 18, 1835, at Fort Gibson at the age of twenty-five years.[

]

- The Choctaw Agency was fourteen miles southwest of Fort Smith and five miles south of Fort Coffee and the Arkansas River. The payments were made here to the Choctaw whose name for money is “Iskuli-fehna” whence the place became known as Skullyville.[

]

- George Birch was born in England and December 12, 1808, was appointed to the army from Pennsylvania; made brevet-major, August 31, 1826, for ten years faithful service in one grade; died September 26, 1837.[

]

- Kappler, op. cit., vol. ii, 322.[

]

- Thwaites, op. cit., vol. xx, 254 ff.[

]

- Notably, a “Map of Texas and the countries adjacent, compiled in the bureau of the Corps of Topographical engineers from the best authorities for the State Department under the direction of Colonel J. J. Abert, Chief of the Corps, by W. H. Emory, First-lieutenant Topographical Engineers War Department 1844.”[

]

- U.S. House. Reports, 23d congress, first session, no. 474. Report of Committee on Indian Affairs.[

]

- John Nicks was born in North Carolina and on July 1, 1808, was appointed captain in the Third Infantry; October 9, 1813, major in the Seventh Infantry and honorably discharged on June 15, 1815. Reinstated December 2, 1815, as captain in the Eighth Infantry with brevet of major from October 9, 1813; major in the Seventh Infantry June 1, 1816, and Lieutenant-colonel June 1, 1819; June 1, 1821, shortly before his regiment removed to Fort Smith, Colonel Nicks was honorably discharged. He was sutler at Fort Gibson from the time of its establishment and was appointed postmaster at the post February 21, 1827, and was therefore the first postmaster within what is now Oklahoma. He was sutler and postmaster there at the time of his death December 31, 1831. In partnership with John Rogers, under the name of Nicks and Rogers, he maintained a trading establishment at Fort Gibson and one at Fort Smith. Upon the death of Major William Bradford, Brigadier-general of Militia of Arkansas territory, Colonel Nicks was by the President appointed to that post in 1827.[

]

- Army and Navy Chronicle (Washington), vol. i, 279.[

]

- Army and Navy Chronicle (Washington), vol. i, 357, 397.[

]

- Davis, Varina Jefferson, Jefferson Davis, A Memoir by his izife. 162.[

]

- Adjutant General’s Office, Old Records Division, Fort Gibson Letter Books 15, 17; Order Book 10.[

]

- Wickliff was dropped from the army rolls April 12, 1842, but was reinstated as captain March 5, 1847; he was honorably discharged July 22, 1848; served with the Confederate army as colonel of the Seventh Infantry; died April 24, 1862 of wounds received at the Battle of Shiloh.[

]