Immediately after the peace of 1763 all the French forts in the west as far as Green Bay were garrisoned with English troops; and the Indians now began to realize, but too late, what they had long apprehended the selfish designs of both French and English threatening destruction, if not utter annihilation, to their entire race. These apprehensions brought upon the theatre of Indian warfare, at that period of time, the most remarkable Indian in the annals of history, Pontiac, the chief of the Ottawa’s and the principal sachem of the Algonquin Confederacy. He was not only distinguished for his noble and manly form, commanding address and proud demeanor, but also for his lofty courage, winning manners and a pointed and vigorous eloquence, which won the respect and confidence of all Indians, and made him a marked example of that grandeur and sublimity of character so often found among his so greatly miscomprehended race. Pontiac had closely watched the slowly advancing power of the English, and their haughty and defiant encroachments upon the territories of his own people and his entire race.

When he was informed of the approach of Major Rogers with a company of English soldiers into his country, the indignation of the forest hero was roused to its highest pitch; and at once he sent a messenger to Rogers, who met him on the 7th of November, 1763, with a request to halt until Pontiac, the chief of the Nation, should arrive, then on his way. As soon as Pontiac came up he boldly demanded of Rogers his business and why he had come with his soldiers into the Ottawa country unsolicited? To which Rogers replied; He had no evil designs against his people, or any of his race; his only object in coming was to remove the French from the country who pretended a mutual friendship and trade between his people and the English. The next morning, after smoking by turns the pipe of peace, Pontiac told Rogers that he would protect him and his party from the attack of his warriors who were already collected at the mouth of Detroit River to stop his further progress. Major Rogers having arrived unmolested at Detroit, he at once entered into friendly negotiations with many of the neighboring tribes; after which he left Captain Campbell in charge of the fort and departed on the 21st of December for Pittsburgh.

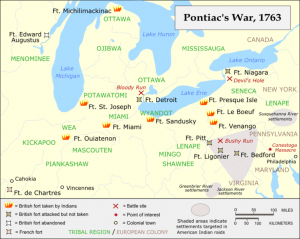

The Indians, throughout the whole of the country formerly occupied by the French, regarded the arrogant English as intruders, and were indignant at the incomprehensible exchange without a voice in the matter; and the smile that might have been observed playing around the mouth of Pontiac when he first met Rogers and his soldiers on the shores of Lake Erie, but concealed the deep cherished hatred he entertained for the English, even as the rays of the setting sun. Bedazzle the thundercloud in the far distant east; as he had only made professions of friendship as a matter of national policy, that he might gain time to mature his plans for the defense of his people and race against the destruction that seemed approaching. Truly, the far-sighted statesmanship evinced in his plans far affecting the expulsion of the English, their assumed friends but deadly foes, and thereby the preservation also of his people and race, proved his possession of an extraordinary courage, and energy of the highest order. His plan was a sudden and contemporaneous attack upon all the English ports everywhere in the Indian territories west of the Alleghany mountains at St. Joseph, Green Bay, Ouiateon, Detroit, Michilimackinac, Maumee, Sandusky, Niagara, Presque Isle, LeBoeuf, Venango and Pittsburgh; the last four mentioned being in Western Pennsylvania. Could the attack be simultaneous, and every English fort upon a line of many hundreds of miles be destroyed upon the same day, no one would be able to give assistance to the other; while, at the same time, the failure of one attacking party would have no deleterious effect upon the other. Thus the war might begin and end in the same day, and the Indians would again be free and in the possessions and enjoyment of the land of their ancestors.

Pontiac first laid his plans before his own people, the Ottawa’s, who at once embraced his propositions and gladly entered into his plans. He then called for a great council of all the tribes to be held at a designated point on the Aux Ecarces River. They responded to the call of the mighty Ottawa, whose name was known far and wide; and it was an assemblage vast of unvarnished, un-panoplied men consulting upon plans for mutual protection against a fearful foe threatening their destruction. Then and there was heard the untaught eloquence of natures orator, the great Pontiac, who in strains of wild eloquence appealed to his hearers’ fears and hopes, their patriotism, their love of freedom and hatred of the English, their oppressors and destroyers; then to their superstitions, by relating a dream in which he told them the Great Spirit (whom all Indians held in great reverence unsurpassed by any nation of people on earth) had revealed to a Delaware prophet the path his red children should pursue; and concluded in a wild tone of voice: “Why, why, said the Great Spirit, angrily to the Delaware prophet, why do you permit those dogs in red clothes to come into your country and rob you of the land and homes I have given you? Drive them back whence they came. If you need assistance, I will help you.”

That was enough. The dawn of the morn of their liberation seemed gloriously appearing in the East. With Pontiac at their head a host within himself and the Great Spirit‘s promised assistance, failure in the great undertaking was impossible. The footprints of the foreign intruder and oppressor were soon to be seen no more upon their soil, and again they were to be free. A plan of action was adopted at once and far and wide, even to the borders of North Carolina, the tribes laid aside their former feuds, became friends and joined the league in common and united effort to rid their common country of its foreign enemies whom they had ignorantly embraced as friends but to find them foes.

Silently and unobserved gathered the clouds of the approaching tempest, while the quiet or fancied security rested upon all. The traders, as usual, traveled from village to village; the idle soldiers dozed away the day in dreamy thoughtlessness and all was calm life; yet unseen, journeyed bands of Red Men through the deep solitudes of the forests, until every English fort was hemmed in by mingled warriors. The day came, and first the traders everywhere were slain. Then every English fort west of the Alleghany Mountains was at once destroyed through the preconceived and prearranged plans of the mastermind of Pontiac, except four, Detroit, Bedford, Ligonier and Pitt.

Detroit was the most important situation to be taken, since, if captured, it would enable the Indians to unite their hitherto separate lines of operation, above and below; there fore, Pontiac, in person, undertook its capture with his own Ottawa warriors. The garrison numbered one hundred and thirty, with forty or fifty traders in the village.

On the 8th of May 1760, Pontiac, with about three hundred warriors, appeared before the gates of the fort, and solicited an interview with the commanding officer, Major Gladwyn; but, alas, for the hopes of Pontiac! A few days before an Indian woman had betrayed the secret to Major Gladwyn, and Pontiac found all on their guard and prepared for an attack. Yet he delayed not, but made a bold attack upon the fort, and adopted every means his ingenuity could suggest destroying it; but after a siege of several weeks he withdrew, having learned of the approach of re-enforcements for the fort. Thus Detroit was saved by the treachery of one of his own race, and Pontiac’s hopes utterly thwarted; and also, as if by miracle, the three above mentioned forts escaped destruction. The noble, sagacious and patriotic Pontiac afterwards fell by the hand of a traitor and assassin, and with his death perished the last hope of the western Indians, who were soon, conquered and humiliated. Ill-fated race! Who but must sympathize with you in your misfortunes.

Discover more from Access Genealogy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.