With the help of contemporary records it is possible to identify some of the early traders at the Mouth of the Verdigris. Even before the Louisiana Purchase, hardy French adventurers ascended the Arkansas in their little boats, hunting, trapping, and trading with the Indians, and recorded their presence if not their identity in the nomenclature of the adjacent country and streams, now sadly corrupted by their English-speaking successors. 1

French Influence in Arkansas

A Choctaw Warrior

1764 – 1824

One of the first of the French traders up the Arkansas whose name has been recorded was Joseph Bogy, an early resident of the old French town, Arkansas Post, from which point he traded with the Osage Indians in the vicinity of the Three Forks. On one of his expeditions he had ascended the Arkansas with a boatload of merchandise, to trade to the Osage near the mouth of the Verdigris. There on the seventh of January, 1807, he was attacked and robbed of all his goods by a large band of Choctaw Indians under the famous chief, Pushmataha. 2 When charged with the offense, Pushmataha admitted it and justified the robbery on the ground that they were at war with the Osage, against whom they were proceeding at the time; and that as Bogy was trading with their enemies, he was a proper subject for reprisal. Bogy laid a claim before the Government for nine thousand dollars damages against the Choctaw, based on the protection guaranteed by his trader’s license. This claim was pending until after 1835, before it was allowed. Among the interesting papers in connection with the claim, is Bogy’s report of having met on his ascent of the Arkansas Lieutenant Wilkinson, who had recently parted from Captain Pike. “But sir, suppose the same Indians (the Choctaws), who fell upon me and plundered my property, had fallen in with Lieutenant Wilkinson, whom I met a few days before, and not far from the place of depredation, (who had parted on the Arkansas with my then brave friend, but now lamented Pike), while he was coming down the river, with but few men, destitute of everything, and whom I furnished with such provisions and ammunitions as it was in my power, suppose the same Indians, I say, had fallen upon him, plundered him and his men… would the Government have interfered in their behalf?” 3

Bogy continued to trade at the mouth of the Verdigris for many years; Nuttall traveled from Fort Smith to the Verdigris in Bogy’s boat, and on July 14, 1819, entered “The Verdigris, where Mr. Bougie and Mr. Prior had their trading houses.” When Nuttall returned to the mouth of the Verdigris, desperately sick from his prairie expedition, he remained a week under the hospitable roof of Mr. Bogy at the trading post, while he gained sufficient strength to descend the Arkansas. 4

In the summer of 1812 a trading party under the leadership of Alexander McFarland left Cadron on the Arkansas to trade with the Indians on upper Red River for their horses and mules. 5 Though they endeavored to avoid the Osage Indians, the latter entered their camp near the Wichita villages, August 13, and killed McFarland while his companions were absent. Subsequently, in 1813, a claim was filed with the government by the widow, Lydia McFarland, for the loss of her husband and his property. In 1814 depositions were given by John Lemmons, who was with McFarland’s party, by William Ingles, Robert Kuyrkendall and Benjamin Murphy. The latter three stated that in October 1812 they were at the mouth of the Verdigris, where the Osage had collected to trade and there were present the band of Osage who had just returned from Red River bearing with them some of the property taken from McFarland. The Cherokee Chief Tallantusky was there in quest of merchandise he had confided to McFarland for trade to the western Indians. Recognizing in the possession of the Osage some of his property including two short swords, he demanded their possession and the Osage gave them up and through Ingles as interpreter admitted to Tallantusky that they had killed and robbed McFarland. From this it appears that there were traders at the mouth of the Verdigris as early as 1812.

One of the early arrivals to establish a trading house at the mouth of the Verdigris was Captain Barbour, who came from New Orleans and entered into partnership with George W. Brand, who, being married to to a Cherokee woman, exercised the privileges of a member of the tribe. Long before the Cherokee were removed from their home on Arkansas River in the present state of Arkansas to their final location, Brand and Barbour built at the Falls of the Verdigris an extensive trading establishment consisting of ten or twelve houses, cleared thirty acres of land, and established a ferry at the same place. In the journal of his expedition, Nuttall speaks of meeting Barbour in January 1820, and traveling on the Arkansas in “the boat of Mr. Barber, a merchant of New Orleans.”

Colonel A. P. Chouteau became the owner of the trading establishment of Brand and Barbour at an early day, 6 and continued so until 1827, when he sold some of his buildings to Colonel David Brearley, to be used as the Creek Agency, the earliest agency to be established within the present limits of Oklahoma. 7

After the treaty of 1828 with the Cherokee conveyed to that tribe the land on which the Creek Agency was located, the Cherokee insisted on its removal, and Brand demanded possession of the improvements. After his death, his heirs pressed their claim for damages for the use of the improvements; and in 1837 the Committee on Indian Affairs of the Senate reported that Brand was entitled to the buildings, field, and falls of the Verdigris, and recommended a bill to compensate the heirs for their use by the Government at the rate of five hundred dollars annually. 8

One of the most romantic figures connected with the trading settlement at the mouth of the Verdigris was Nathaniel Pryor, a veteran of the War of 1812, and a sergeant with the memorable Lewis and Clark Expedition to the mouth of the Columbia in 1804, in which he had a creditable part. Almost continuously after that service, he was engaged in trading with the Indians except when he answered the call of his country during the war with England. Soon after the war he ascended the Mississippi and Arkansas to Arkansas Post, from which point, with a partner, Samuel B. Richards, he engaged in trading with the Indians up Arkansas River. Shortly after the organization of Arkansas Territory, a license was issued by the governor, November 29, 1819, 9 “to Nathaniel Pryor, to trade with the Osage Nation of Indians, as well as to ascend the river Arkansas with one trading boat to the Six Bull or Verdigree, together with all hands that may appertain thereto.”

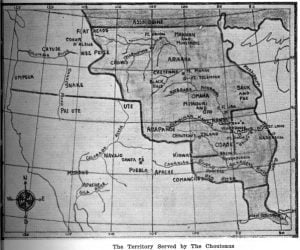

Pryor built a trading store about one and one-half miles above the mouth of Verdigris River, and with an Osage wife lived ten years in the vicinity until his death. He had great influence with the Osage Indians, with whom he was an active trader. He was held in the highest esteem by the white officials and others who subsequently came to Fort Gibson, and who repeatedly urged upon the War Department the wisdom of appointing Pryor to a responsible position in connection with the Indian service, for which, by his long experience and standing with the Indians, he was preeminently qualified. Indifferent to these considerations, official Washington permitted his talents to go all but unnoticed. Though Pryor was industrious and honest, he was equally unfortunate in his private business. He held the friendship of those who knew him, and became one of the dominating figures of the little colony at the mouth of the Verdigris, exerting its influence over the entire Southwest.

Another well-known trader at the mouth of the Verdigris at this period was Hugh Glenn, who headed the Fowler expedition in 1821, the first to go from there to Santa Fe. Colonel Hugh Love was also a trader in this frontier settlement.

Auguste Pierre Chouteau

As an active trader and man of influence among the Indians, A. P. Chouteau was the outstanding figure of all those in business at the mouth of the Verdigris. Chouteau had for several years traded with the Indians on the headwaters of the Arkansas and Platte rivers, but abandoned the hazards of that field in 1817. In September, 1815, Colonel Chouteau and Julius De Mun, with forty-five men, engaged in a trading expedition to the Arapaho Indians at the head waters of Arkansas River. They were having a successful winter when in February De Mun with two companions returned to Saint Louis for additional supplies. In July he started back, proceeding up Missouri River by boat to join Chouteau at the mouth of Kansas River. The latter, in coming east, had been attacked by two hundred Pawnee 10 Indians at a place since called Chouteau’s Island, near the present site of Fort Dodge, Kansas, but he arrived at the appointed place with his furs; these he and De Mun sent down the river to Saint Louis, and again turned their faces to the Rocky Mountains. In their absence, a friendly governor at Santa Fe had been succeeded by one hostile to Americans. Disregarding the permission granted by his predecessor for the Americans to enter the Spanish territory, the governor caused the arrest of Chouteau and De Mun with their men, as they were about to leave the Arkansas for the Crow Indian country on Columbia River. They were thrown in prison at Santa Fe, where they were confined for forty-eight days, part of the time in irons; their lives were threatened, and they were subjected to other indignities; the final and most poignant of all was compelling Chouteau and De Mun to kneel to hear a lieutenant read the sentence pronounced by the governor, and then “forced likewise to kiss the unjust and iniquitous sentence, that deprived harmless and inoffensive men of all they possessed – of the fruits of two years’ labor and perils,” as reported by them to our Government. 11 This sentence of the governor gave them their liberty, but confiscated all their property, valued at over thirty thousand dollars. A claim for this loss was made by the United States, but it was not paid for over thirty years – long after Chouteau’s death. 12

Some years after this incident, in answering a letter from the Secretary of War, inquiring about trading conditions in the west, Colonel Chouteau wrote from the Verdigris: 13

“Shortly after the war I went upon a trading expedition on the head of the Arkansas and was taken by the Spaniards. When I was near Santa Fe, I was invited by them to visit their place. Convinced of my own innocence and believing the invitation to be an act of hospitality, I unhesitatingly accepted what I believed was intended as a mark of respect. Immediately upon my arrival in town I was arrested, thrown into prison, charged with revolutionary designs, my property confiscated, and after having undergone an examination in which my life was endangered, I was discharged without any compensation for my property which had been taken by violence.

“On my return home I was determined to abandon a trade that was attended with so much risk until the time when the United States Government would extend its protection to those citizens who embarked their capital and risked their lives in a trade that ultimately must produce advantages to the citizens of the United States, and in a political point of view cement the bonds of friendship between the governments of the United States and Mexico.”

The Indian trade at the Verdigris was conducted for the sake of the furs, skins, and bear oil the Indians brought to the trading post. Wild bees were abundant, and honey and beeswax found a ready market. Wild horses, buffalo, elk, and deer ranged the prairies, and beaver, bear, wolves, otter, fox, wildcats, panthers, turkeys, ducks, and swans were found in vast numbers. The Indians brought to the Verdigris the fruits of the chase and the trap, to exchange for the earrings, strouds, twists of tobacco, pipes, rope, vermillion, axes, knives, beads, cheap jewelry, and bright-colored cloth, which constituted the medium of exchange.

Chouteau had another trading house at the Saline on Grand River, near where Sarpy now is, where he built up a comfortable country seat which was visited and described by Washington Irving in 1832. 14 The Saline was distant from the mouth of the Verdigris about thirty-five miles overland and sixty by canoe.

From the trading house at the mouth of the Verdigris in 1823 and 1824 Chouteau wrote in French a number of letters to his cousin, P. Milicour Papin, at the Saline, 15 relating to the business in which several members of the family were engaged, and which he supervised so efficiently from the “Ver di Gris”; gave directions in several quarters, warned Milicour against Mr. Guilless who is going to call at “La Saline”; “he is a good fellow, but one must be wary of him for he has some merchandise,” and might beguile the Osage Indians into bartering to him the peltry that Chouteau hopes to ship to New Orleans that winter. However, treat him well for he is one of Menard’s 16 men, and that means a great deal to me.” It is the eleventh of December, 1823, and Chouteau deplores the fact that the Indians have done less hunting that season than formerly; however, he hopes to secure forty to sixty more packs before very cold weather sets in. And he tells with some relish how his friend Clermont, the Osage chief, ordered some of “Les Loups” not to hunt on Osage lands. After expressing his appreciation for the news from “La Saline”, he warns Milicour not to sleep too much during the day, or the business will not prosper.

He wrote to Milicour, January 3, 1824, that he has just had a letter from his brother Ligueste, who is among the Little Osage on the headwaters of Osage River, many miles north of the Arkansas Osage. He has little faith in the business sagacity of Ligueste, who reports that he has made ninety-two packs with the Little Osage without informing him how many pelts each pack contains. He warns Milicour of the presence of another white trader poaching on the Osage farther north, and commands his cousin to send for the Indians at once to bring in their peltries before their competitor appears among them, or make himself responsible for the value of the furs that are lost.

The fur trader had his losses to recoup too “should Campbell come by here, we must try to make him trade off, by means of the Indians, all of our defective skins as well as our imperfect cats.” The mouth of the Verdigris was the emporium of the Southwest; merchandise that came up-stream by keel boat from New Orleans and Saint Louis was distributed from here. Chouteau was sending to Ligueste “150 twists of tobacco, 10 pounds of vermillion and 13 of Rasedez”; and to Milicour went a small chest with some Christmas gifts which he was requested to share “with Madam Rivar and my old woman.” Beside directing Milicour to take good care of the boat, he was told to make his preparation to go to Chihuahua on a two months’ trip in the summer.

Again, on January 12, he wrote a long letter of advice and directions about the business; information concerning pelts acquired and owing to the house; Milicour must do all in his power to keep the Osage of Pahuska’s or White Hair’s town from coming down to the mouth of the Verdigris; “tell them that you are expecting me [at the Saline] any day; I must tell you, however, that it is quite impossible that I go. Much of our credit has not been turned in, and the affairs between the Osages and the Government, 17 not having been settled, prevents my leaving, for fear something should turn up, which some one else would not be able to settle; I do not remember whether I told you about Goche; he gave me 50 pelts for his credit, and since that he has had a cotton cloth with three stripes, which is worth 16 pelts. The Indians like it, but they are too poor to buy it. Next Monday at the latest, I shall send my men to the Saline. Work has been started on the small barge, but unfortunately, from present appearances, we shall not need it for December.”

However, on the second day of April, the large barge left down-stream with a cargo of thirty-eight thousand seven hundred fifty-seven pounds of furs and skins; the shipment included three hundred eighty-seven packs and fifty-seven pounds, made up of three hundred female bear skins, one hundred sixty bear cubs, three hundred eighty-seven beavers, sixty-seven otters, seven hundred twenty cats, ninety-five “Pinchon” and fox, and three hundred sixty-four packages of deer skins, which included seven hundred twenty-six deer skins belonging to Mr. Menard. This information is contained in a letter written at “Ver de Gris” on April 4. It contained the news also of the drowning of Mr. Philbrook, the Osage sub-agent. He had been at Bean’s salt works on the Illinois, and was returning to his post when, attempting to cross Grand River near the mouth, he was drowned. Young Pryor came by the place a few days later, and discovering Philbrook’s horse, bridle, saddle bag and “cloque”, learned the sad story of his death.

Two days later Chouteau wrote Milicour again. He was accompanying the valuable cargo of peltry, but would be unable to go all the way to New Orleans with the boat. The troops from Fort Smith were on their way to the mouth of the Verdigris, where they were to establish a new army post, and Chouteau felt the necessity of returning soon. The Indians were troublesome, and were likely to become involved with the troops that were about to be located near them. To maintain his influence with the Osage, he must be near at hand to advise them if the proximity of the soldiers threatens them with difficulties. Also there was the business to be had of securing provisions for the troops. He was disappointed that Ligueste had not sent his furs down Grand River in time to accompany the shipment to New Orleans. He directs Milicour to arrange his bear pelts in packs of twenty each, and to send them down at once, as they must be in New Orleans by May first, or they will lose money on the shipment. The packs must be marked so he can tell the female from the male bear pelts. “I send you four battle-axes with which to procure oil; you may trade one axe for one font of oil and even something extra thrown in.” Chouteau was interested in live stock, and later had a race-track at the Saline. He warns Milicour not to let any of the visitors at the Saline beat or run his horses too hard, and when taking horses for transporting furs not to use the plow-horses. 18

Citations:

- Many tributaries of Arkansas River originally bore French names. There was the Fourche La Feve named for a French family [Thwaites, R. G., editor, Early Western Travels, vol. xiii, 156]; the Petit Jean or Little John, named for a Frenchman of small stature who was killed on its banks by the Indians [Thwaites, R. G., editor, Early Western Travels, vol. xiii, 171]; Vache Grasse Creek these and others bearing French names were noted by Nuttall within the present limits of Arkansas. Lee’s Creek emptying in the Arkansas near Fort Smith was called river au Milleau by Lieutenant Wilkinson in 1807. The Poteau flows into the Arkansas at Fort Smith; the word being French for Post, may have been given to the river by some unhistoric French station [Thwaites, R. G., editor, Early Western Travels, vol. xiii, 199 n]. The Sallisaw was named by the French the Salaison, from meat having been salted there, and from that the transition was easy to Salaiseau and then to the present rendering [Thwaites, R. G., editor, Early Western Travels, vol. xiii, 231]. Vian Creek was originally Bayou Viande. But consider the sad case of the creek bearing the name of Dardenne a prominent early French family mentioned by Nuttall [Thwaites, R. G., editor, Early Western Travels, vol. viii, 136], living on the north side of Arkansas River below where is now Pine Bluff. Map makers afterwards shortened this name to Derden, and now, alas, it has descended to the appellation of Dirty Creek. It debouches into the Arkansas about twenty miles below Muskogee. One of the main forks of Grand River was at an early day called Pomme de terre River. Cache creek, of course, is French, as likewise is Verdigris. The tributaries of the Arkansas from the west testify to their Spanish origin. While the Arkansas bore that name throughout its length it was often called by the early trappers Pawnee River above the Three Forks. The first fork of the Arkansas noted by Pike, was called by the French, Riviere Purgatoire and by the Spaniards, Rio Purgatorio and Rio de Las Animas. The English speaking successors have changed this pronunciation and now this creek in eastern Colorado from Purgatoire has become Picket-wire.

Cimarron, the name of the tributary entering the Arkansas from the west, also formerly called Red Fork, is a Spanish-American word meaning something wild, runaway, or unreclaimed [Coues, Expeditions of Zebulon M. Pike, vol. ii, 438, n]. It was sometimes known as the “Semerone of the Traders.” ” ‘Canadian,’ as applied to the main fork of the Arkansas has no more to do with the Dominion of Canada in history or politics than it has in geography, and many have wondered how this river came to be called the Canadian. The word is from the Spanish Rio Canada, or Rio Canadiano, through such form as Rio Canadian, whence directly ‘Canadian’ r., meaning ‘Canon’ r., and referring to the way in which the stream is boxed up or shut in by precipitous walls near its headwaters.” – [Coues, Expeditions of Zebulon M. Pike, vol. ii, 558 n, 17.] The North Fork of Canadian River was by the early trappers and traders called Rio Nutria a Spanish name meaning Otter River. It was also called Rio Rojo, and Rio Roxo, Spanish for red river. One of its tributaries was called Rio Mora, a Spanish word meaning mulberry. Red River was called by the Spanish Rio Roxo and Rio Colorado. False Washita was called also Rio Negro, Spanish for black river. Brazos river of Texas was named by the Spaniards ” ‘el Rio de los Brazos de Dios,’ River of the Arms of God, which seemed neither blasphemous nor sacrilegious to the admirable fanatics who so solemly theographized geography in their excursions for the salvation of souls,” – [Coues, Expeditions of Zebulon M. Pike, vol. ii, 706, n. 13.]

The influence of the French on the Indian tribes of the Arkansas valley was important. They intermarried freely with the Quapaw and Osage and not only named many individual Indians of those tribes but gave the Osage tribe its name. Osage is the corruption by the French of Wazhazhe, their own name (Handbook of American Indians, vol. ii, 156). Cheveu Blanc or White Hair and Pahuska are the several names of one of the most celebrated Osage chiefs. Belle Oisseau Beautiful Bird, of course was named by the French. The name of the chief Clermont also is French. The name Akansea, adopted by the French, is what the Quapaw were called by the Illinois Indians and is the origin of our Arkansas or Arkansaw [Coues, Expeditions of Zebulon M. Pike, vol. ii, 559, n. 20] [Thwaites, R. G., editor, Early Western Travels, vol. xiii, 117]. The Quapaw tribe is now the only remnant of the Arkansea. A band of Illinois Indians lived with the Akansea on Arkansas River [Handbook of American Indians, vol. ii, 335] and they or French trappers from the Illinois country probably were responsible for the naming of the Illinois rivers emptying into the Arkansas, one in the present limits of the state of that name and the other in Oklahoma. Little Rock was called La Petite Rochelle by the French, to distinguish it from the larger rocky promontory two miles farther up the river [Thwaites, R. G., editor, Early Western Travels, vol. viii, 146].[

]

- For an account of Pushmataha, see U.S. Bureau of Ethnology, Bulletin 30, Handbook of American Indians, part ii, 329, 330.[

]

- U.S. Senate, Documents, 24th congress, first session, no. 23. Petition of Joseph Bogy praying for compensation for spoliation by Choctaw Indians while on trading expedition on Arkansas River.[

]

- Thwaites, R. G., editor, Early Western Travels, vol. xiii, 277.[

]

- Indian office, Old Files. Special case 191.[

]

- The purchase was probably made just prior to the time of Barbour’s descent to New Orleans and his death, which occurred early in 1823.[

]

- The Creek Agency “is situated immediately on the eastern bank of the Verdigris three of four miles from its mouth.” – U.S. House, Reports, 20th congress, second session, no. 87. Report of Committee on Indian Affairs, 41. In 1827 Major McClelland, Choctaw Agent occupied some of the government buildings at Fort Smith, that had been left in charge of Nicks and Rogers. They were located on land claimed by the Choctaw, (Arbuckle to Jesup, February 26, 1827, Quartermaster’s Depot, Old Files).[

]

- U.S. Senate, Documents, 24th congress, second session, no. 47, Report of Senate Committee on Indian Affairs on petition of George W. Brand with Senate Bill no. 91.[

]

- Vashon to Cass, April 30, 1832 (enclosure) Indian Office 1832 Cherokee West Agency.[

]

- “A Mr. Chouteau and party had been attacked by 150 Pawnees. He had one man killed and four wounded; but he defeated the Savages, killed seven and wounded several others and brought in 44 packs of beaver, that is about 4,400 pounds.” – Niles Register (Baltimore) October 19, 1816, vol. xi, 127.[

]

- American State Papers, “Foreign Relations” vol. iv, 211.[

]

- From the files of the Saint Louis, Missouri, County Court. In the matter of the Estate of August P. Chouteau deceased, John B. Sarpy, administrator. Payment was made about 1850.[

]

- Chouteau to Secretary of War, Nov. 12, 1831, Indian Office, Retired Classified Files, 1831 Miscellaneous.[

]

- Trent, William P. and George S. Hellman. The Journals of Washington Irving, The Bibliophile Society, vol. iii, 131.[

]

- Missouri Historical Society, Saint Louis, Missouri, “Pierre Chouteau Collection.” Translated by Mrs. N. H. Beauregard, Archivist.[

]

- Pierre Menard was born October 7, 1766, at San Antoine, Quebec, came to Vincennes in 1788, and Kaskaskia in 1790. He was Lieutenant-governor of Illinois in 1818, and died in 1844. He was an active fur trader dealing with the Indians, and was one of the partners in the Missouri Fur Company which included A. P. Chouteau and his father Pierre Chouteau. A. P. Chouteau shipped from the mouth of the Verdigris seven hundred twenty-six deer skins belonging to Menard. Bayou Menard a small stream flowing into the Arkansas below Fort Gibson was so named prior to 1820 when it was mentioned in the account of Long’s Expedition [Thwaites, R. G., editor, Early Western Travels, vol. xvi, 285]. The mountain south of this stream was called Menard Mountain.[

]

- Which were soon to cause the establishment of Fort Gibson.[

]

- In December, 1831, George Vashon, Cherokee Agent, issued licenses to traders in the Cherokee country including A. P. Chouteau near the Falls of the Verdigris and on the east side of the river; Hugh Love at the same place, but on the opposite side of the river. Eli Jacobs was his clerk. Thompson & Drenen at the Point, between the Neosho and the Verdigris; Jesse B. Turley also at this Point, and A. P. Chouteau on the Neosho near Grand Saline. Seaborne Hill was later located at the mouth of the Verdigris. Benjamin Hawkins, who was married to a Cherokee woman, was a trader in that nation and a friend of Sam Houston’s. Sixty barrels of whiskey delivered to Hawkins on the Verdigris by the steamboat Elke in 1832, caused a grand jury inquisition at Little Rock. Hill was killed at Fort Gibson in July, 1844, by Captain Dawson and a man named Baylor. – Fort Gibson Letter Book no. 17, p. 140.[

]