In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Cherokee faced increasing pressure from American expansion. This pressure led some Cherokee to consider relocation west of the Mississippi River well before the infamous Trail of Tears. Between 1782 and 1835, a series of voluntary migrations, treaties, and official rolls documented Cherokee families moving west. These Emigration Rolls during 1817–1835 are valuable genealogical records as they list Cherokee heads of households, number of family members and their ages, slaves, and other details. This report provides a historical overview of Cherokee westward migration during this period, beginning with a 1782 proposal to Spanish authorities, and continuing until the Treaty of New Echota in 1835.

Spanish Permission in 1782

In the aftermath of the American Revolution, some Cherokee sought refuge from encroaching settlers by moving west. In 1782, a Cherokee contingent led by Chief Standing Turkey (Conocotocko) petitioned the Spanish colonial government for permission to settle in Spanish Louisiana (the territory west of the Mississippi). The Spanish governor granted this request, allowing this group to relocate into what is now Missouri. This marked the first documented Cherokee emigration west of the Mississippi. These early western Cherokee settlers were likely those who had fought alongside the British in the Revolution and were looking for distance from the new United States. They established villages in the Mississippi River watershed under Spanish rule.

Around the same time, a faction of Cherokee known as the Chickamauga (followers of Dragging Canoe) moved south and west but remained east of the Mississippi, in the remote Tennessee and Alabama frontier, to resist American settlement. Dragging Canoe’s move, though not across the Mississippi, is part of the broader Cherokee response to American pressure – some groups chose armed resistance in the East, while others chose migration to more distant lands.

Spanish Louisiana provided a temporary haven. Through the 1780s and 1790s, more Cherokee families drifted west into what is now Arkansas. By the mid-1780s, as many as 1,000 Cherokee had moved into Spanish territory west of the Mississippi. They settled in the St. Francis River valley and Crowley’s Ridge area of eastern Arkansas, then Spanish Missouri Territory. These settlements left their mark in local place names – for example, “Doublehead Bluff” for Cherokee leader Doublehead and Big Telico Creek, named after a Cherokee town in the East. Early Cherokee leaders of these migrant groups included figures like John Hill (Connetoo), George Duvall, Moses Price (Wohsi), White Man Killer (Unacata), and William “Red-Headed Will” Webber, who led parties of families into the Arkansas frontier.

The New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811–1812

A major turning point for the western Cherokee settlements came with the New Madrid earthquakes of 1811–1812. Centered in the Missouri Bootheel, these massive quakes were among the strongest in U.S. history and were felt across the region. The quakes caused geological upheaval, even briefly making the Mississippi River run backward, and deeply affected Native communities. In Cherokee settlements along the St. Francis River, the earthquakes were interpreted as ominous signs. A Cherokee spiritual leader named The Swan (Skawuaw) emerged with a prophetic warning: in June 1812 at the Cherokee village of Crowtown, he preached that the quakes were a divine judgment and that more destruction would follow unless the Cherokee rejected Anglo-American ways and possibly moved from the area.

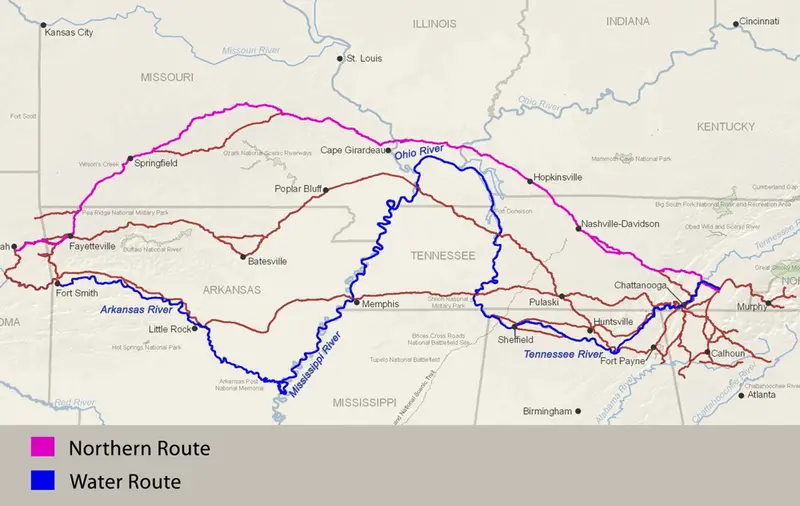

In response, many Cherokee abandoned their villages in eastern Arkansas after 1812. They migrated further west into the Arkansas River Valley, in what is now western Arkansas, seeking higher ground and stability. The Arkansas River Valley’s wooded hills resembled the Appalachian homelands they had left, making it a desirable new refuge. However, this move put the Cherokee into direct conflict with the Osage Nation, who claimed that area as hunting grounds. Violence flared between Cherokee newcomers and Osage warriors over territory and resources. The U.S. government, now sovereign over the Louisiana Purchase, intervened by establishing Fort Smith in 1817 on the western Arkansas border. The fort’s purpose was to keep peace between the Cherokee and Osage.

Despite these challenges, the Cherokee presence in Arkansas continued to grow as new groups arrived from the East throughout the 1810s. Not all went to the Arkansas River Valley; some families pushed even further southwest. Notably, Chief The Bowl (Duwa’li) led a band of Cherokee to Spanish Texas around 1819. The Bowl’s band had originally settled on the Arkansas River’s south side, but after the Treaty of 1817 required all Arkansas Cherokee to move north of the river, The Bowl chose instead to lead his people to Texas, then under Spanish rule. There they became known as the “Texas Cherokees,” settling in East Texas – another chapter of westward Cherokee migration beyond U.S. jurisdiction. The Texas Cherokee would later face their own difficulties with Mexican and Texan authorities in the 1820s–1830s.

Treaties of 1817 and 1819

As Cherokee migration westward increased, the U.S. government sought formal arrangements to facilitate and control the process. Two landmark treaties – in 1817 and 1819 – redefined Cherokee lands and created the first official division between “Eastern” and “Western” Cherokee. These agreements arose from differing Cherokee responses to U.S. pressure: some leaders favored adopting agriculture and staying put, while others favored emigration to preserve traditional life.

- Treaty of 1817 (Turkeytown Treaty) – Signed July 8, 1817, this was the first treaty in which part of the Cherokee Nation agreed to exchange land in the East for land in the West. The U.S. commissioners included General Andrew Jackson (representing the federal government fresh off his military victories). On the Cherokee side, there were representatives of both factions: chiefs from the Nation east of the Mississippi, and a delegation representing the Cherokee already on the Arkansas River (west). Under the Treaty of 1817, the Cherokee Nation ceded large tracts of its eastern territory (parts of Georgia and Tennessee) to the U.S. In return, the U.S. allotted a vast area in northwest Arkansas (between the Arkansas and White Rivers) to the Cherokee who would “remove” to that region. The treaty promised that those who relocated would have this new western land “guaranteed … forever” by the United States (Treaty with the Cherokee, 1828, In fact, about 7 million acres were set aside in Arkansas for the Cherokee under this and subsequent agreements.)

Importantly, the 1817 treaty tried to accommodate both Cherokee factions’ wishes. Article 8 allowed any Cherokee who chose to remain in the East to do so as individual citizens on a 640-acre reserve (essentially private property). Several hundred Cherokee families took this option, receiving individual reservations within the ceded lands (especially in Tennessee and Alabama). A Reservation Roll of 1817–18 was compiled listing those heads of families who claimed such reserves. Meanwhile, those who wished to emigrate were encouraged to enroll for removal. The treaty even authorized an earlier request by the Lower Cherokee or Chickamauga Cherokee for an exploring party to go west in 1809 and pick a suitable location. After the treaty, the U.S. provided flatboats and provisions to assist the move of the first large groups west.

- Treaty of 1819 – Not all Cherokee agreed with the 1817 deal, and many had refused to move. As a result, two years later on February 27, 1819, a second treaty was signed in Washington, ceding additional Cherokee lands that lay within Tennessee and North Carolina in exchange for finalizing arrangements for those who had emigrated. The 1819 treaty essentially acknowledged that a portion of the Cherokee had moved west and fixed a boundary between the remaining Eastern Cherokee lands and the Arkansas Cherokee lands. It also reaffirmed rights of those Eastern Cherokee who had taken 640-acre reservations (and provided a process to register those claims). After 1819, the Cherokee Nation East was left mostly with territory in northwest Georgia, northeast Alabama, and western North Carolina – a shrinking domain, but one they hoped to hold forever. By 1820, as a result of these cessions, most Cherokee lands in Tennessee (and portions of Alabama) were gone, and U.S. settlers were quick to occupy them.

These treaties formalized a split in the Cherokee Nation. Those who had moved to Arkansas became known as the Cherokee Nation West, while those remaining in the original homeland were the Cherokee Nation East. Within the Cherokee Nation East, many viewed the 1817 treaty with bitterness, considering it a betrayal by the minority who left. Indeed, the Cherokee National Council (dominated by those in the East) initially opposed the treaty and tried to block further emigration. Tensions grew between the two groups of Cherokee, though they were still kin. Over the next decade, both groups worked to establish stable governments in their respective locations.

The Cherokee Nation West in Arkansas

By the early 1820s, thousands of Cherokee were living in the Arkansas Territory on the lands set aside for them. They established farms, built communities, and even created a political structure mirroring the one back East. Chiefs Tahlonteeskee (a brother of Doublehead) and later John Jolly served as Principal Chiefs of the Cherokee Nation West. The Western Cherokee made progress: they invited the famed Cherokee scholar Sequoyah to join them, and by 1821 Sequoyah had brought his newly invented syllabary to Arkansas, greatly boosting literacy among Cherokee on the frontier.

However, the Cherokee Nation West’s existence in Arkansas was short-lived. American settlers continued to pour into Arkansas Territory, and they resented the sizable Cherokee domain in the northwest of the territory. Despite the U.S. government’s guarantee “forever” of the Cherokee land, it soon became clear that “forever” was fleeting. By the mid-1820s, pressure mounted to remove the Cherokee from Arkansas as well. The Treaty of Washington 1828 was the result. In that agreement negotiated by Secretary of War James Barbour and signed May 6, 1828, the Western Cherokee ceded all their Arkansas lands to the U.S., and in exchange were granted new lands farther west in “Indian Territory” (present-day Oklahoma). The 1828 treaty’s preamble frankly noted that the Cherokee in Arkansas were “unfortunate” in their location, as Arkansas was becoming a state and whites would soon surround them. To prevent conflict and “future degradation and misery” for the tribe, a new permanent home was delineated out West – with a solemn promise that this new land (a portion of what is now Oklahoma, seven million acres) would “remain theirs forever, … not be included within the limits of any State.” Ironically, this is essentially the same promise made in 1817, now repeated further west.

Following the 1828 treaty, the “Old Settler” Cherokee (as those already out West came to be called) moved quickly out of Arkansas. By 1830, most had relocated to the designated Indian Territory land in what is now northeast Oklahoma. They left behind homes, farms, and mills in Arkansas, which were promptly occupied by white settlers as Arkansas Territory prepared for statehood. The Cherokee who relocated to Indian Territory continued their autonomous government there, with John Jolly as principal chief. Under tragic circumstances they would soon be joined by the thousands of Cherokee who had remained in the East but traveled West along the Trail of Tears.

Emigration Rolls (1817–1835)

Throughout this period of voluntary westward movement, the U.S. War Department’s Office of Indian Affairs kept detailed lists of Cherokee emigrants. These records, known collectively as the Cherokee Emigration Rolls, cover the years 1817 through 1835 (and slightly beyond, up to 1838). They are essentially muster rolls or enrollment lists of Cherokee individuals and families who agreed to move west prior to the Treaty of New Echota (1835). The rolls were created to track who had emigrated (or intended to), for purposes of land apportionment, compensation for improvements left behind, and later, distribution of western land and supplies. Today, these Emigration Rolls are an important genealogical resource, preserving the names of many Cherokee ancestors and their family groupings during this era of voluntary removal.

Content of the Rolls

The Emigration Rolls typically list the name of the head of each household, often along with the number of males and females in the family, and sometimes additional details. For example, an entry might read something like “Joseph Keeton – 5 “reds”, 3 blacks – Hightower, GA,” indicating Joseph Keeton’s family of eight from the Hightower area enrolled to emigrate on 27 Jan 1832. Early rolls (1817–1819) are basically rosters of those Cherokee who “wish to emigrate” from various regions of the old Nation (Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina). Later rolls became more detailed. A Quarterly Return of Emigrants in 1829–1830, for instance, included columns for each person’s “Nation/District” (their residence in the East), their “date of removal,” whether they were full-blood or mixed-blood (“Indian or mixed”), and even how many slaves they owned and the acreage of their improvements. This level of detail was recorded to ensure that those who emigrated were compensated for property left behind and to aid in the logistics of resettlement. One such 1829 report lists emigrants and notes their abandoned farms, mills, or cabins to be evaluated. In summary, the Emigration Rolls captured not just names, but a snapshot of each migrating family’s size and status.

Notable Rolls in this period include:

- 1817–1819 Emigration Roll: A chronological list of Cherokee individuals/families who enrolled for emigration right after the 1817 treaty. Many entries are dated in late 1817 or 1818, as parties organized to depart. Complementing this was the 1817 Reservation Roll of those claiming reserves in the East.

- 1828–1830 Rolls: Lists compiled when the Arkansas Cherokee were moving to Oklahoma. They enumerate families removing under the 1828 treaty provisions and often include the aforementioned details like blood status and number of slaves.

- 1831–1835 Rolls: Ongoing enrollment of those Eastern Cherokee who, under increasing pressure from the 1830 Indian Removal Act, decided to emigrate before forced removal. For instance, an 1834 muster roll records Cherokee from Georgia who moved west that year.

It is important to note that most Cherokee did NOT emigrate voluntarily in this period. By 1835, perhaps 4,000–6,000 “Old Settler” Cherokee were living in the West, while the majority (around 16,000) still remained in the East. Those remaining were enumerated in a comprehensive census known as the 1835 Henderson Roll, which listed all Cherokee in the East by name on the eve of forced removal. (The Henderson Roll, while not an emigration roll, is a key genealogical record alongside them, as it provides the baseline of who had not yet emigrated by 1835.)

Genealogical Value

The Cherokee Emigration Rolls are invaluable for genealogy and tribal history. They preserve the names of heads of households (and an occasional dependent name), often giving clues to family size and location. Researchers tracing Cherokee ancestry often consult these rolls to see if an ancestor left early for Arkansas/Oklahoma or stayed behind. For example, one might find an ancestor listed in December 1818 with a note “enrolled for emigration – did not go,” which tells a story in itself. The rolls also distinguish different Cherokee groups: some entries refer to “Valley Towns Cherokee” (North Carolina) vs. those from Georgia or Tennessee, etc., indicating tribal town or regional affiliations. By comparing the various rolls and later records (like the 1851 Old Settler Roll or 1852 Drennon Roll), families can be tracked through the upheaval of removal.

These rolls have been transcribed and published in modern times – notably by historian Jack D. Baker, whose book Cherokee Emigration Rolls, 1817–1835 compiles these lists. The original records are held by the National Archives (National Archives Identifier 595427), and microfilm copies can be accessed through libraries and archives.

1835 and the Treaty of New Echota

By the mid-1830s, Cherokee autonomy in the East was hanging by a thread. Georgia had extended state laws over the Cherokee Nation, missionaries like Samuel Worcester were arrested for aiding the Cherokee, and federal troops were stationed nearby. While Chief John Ross and a majority of Cherokee continued to resist ceding their land, a small group of leaders, mostly from the Treaty Party led by the Ridges, Elias Boudinot, and others, decided to negotiate terms for removal. On 29 December 1835, without authorization from the Cherokee National Council, this group signed the Treaty of New Echota.

Under the Treaty of New Echota, the Cherokee Nation ceded all remaining lands east of the Mississippi to the United States. In return, they were to receive $5 million, new land in Indian Territory, essentially confirming the 1828 boundaries, and various other provisions, including an annuity and a pre-removal two-year grace period. Though protested by John Ross and the majority, the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty in 1836 by a one-vote margin. This treaty marked the end of the period of “voluntary” westward migration and the beginning of forced removal.

Even after 1835, a few hundred Cherokee still tried to emigrate on their own rather than wait to be forced. But by 1838, the U.S. military, under Gen. Winfield Scott, rounded up the remaining Cherokee in North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama. In the Trail of Tears of 1838–1839, some 15,000 Cherokee men, women, and children were marched or transported to Indian Territory under harsh conditions. Thousands died from disease, exposure, and exhaustion. This tragic finale is outside our 1782–1835 timeframe, but it is the direct outcome of the events described above.

Conclusion and Sources

Between 1782 and 1835, the Cherokee experienced a profound geographical and cultural shift. What began as a trickle of voluntary emigrants seeking new lands under Spanish rule became, under increasing duress, a flood of forced migrants losing their beloved homelands. The Cherokee Emigration Rolls of 1817–1835 bear witness to the names and families who undertook the difficult journey west in those years prior to the Trail of Tears. They show that hundreds of Cherokee families tried to carve out a future in the West on their own terms – whether in Arkansas, Oklahoma, or even Texas – before the U.S. government ultimately forced the remainder from the Southeast. Key figures like Standing Turkey, The Bowl, Sequoyah, John Ross, and Major Ridge each represent different facets of how the Cherokee responded to an existential crisis: with negotiation, accommodation, resistance, or escape. The treaties they signed, or in some cases opposed, chart the incremental dismantling of Cherokee territory in the East and the establishment of a new Cherokee Nation in the West.

For further research, historians and descendants can consult digitized primary sources that illuminate this era. The texts of treaties (e.g., the Treaties of 1817, 1819, and 1828) are available. The U.S. Congressional Serial Set contains reports like an 1828 War Department letter listing Cherokee reservation holders under the 1819 treaty. The National Archives has preserved the original Cherokee Emigration muster rolls and lists of “persons who have emigrated” (NAID 595427), and microfilm/online resources can be found via the National Archives, FamilySearch, and state historical societies. These documents – combined with Cherokee oral histories and later records like the 1851 Old Settler Roll – help paint a comprehensive picture of Cherokee families’ journeys. Despite the great upheaval between 1782 and 1835, the Cherokee Nation endured: reestablished in Oklahoma, the Nation later reunified with the Old Settlers, and today the Cherokee people remember both the hardships of removal and the endurance of those who went before.

Sources

- AccessGenealogy.com, Indian Treaties Acts and Agreements. Cherokee: Treaty of July 8, 1817, also known as the Turkeytown Treaty.

- AccessGenealogy.com, Indian Treaties Acts and Agreements. Cherokee: Treaty of February 27, 1819.

- AccessGenealogy.com, Indian Treaties Acts and Agreements. Cherokee: Treaty of May 6, 1828.

- AccessGenealogy.com, Indian Treaties Acts and Agreements. Cherokee: Treaty of 29 December 1835, also known as the Treaty of New Echota.

- Starr, Emmett. History of the Cherokee Indians and Their Legends and Folk Lore. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: The Warden Company. 1921.

- Logan, Charles Russell, The Promised Land: The Cherokees, Arkansas, and Removal, 1794-1939, originally published by the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, 1997.

- Encyclopedia of Arkansas – Cherokee, https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/cherokee-553/ : accessed 1 May 2025.

- National Park Service, The Trail of Tears and the Forced Relocation of the Cherokee Nation, https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-trail-of-tears-and-the-forced-relocation-of-the-cherokee-nation-teaching-with-historic-places.htm : accessed 1 May 2025.