By the year of 1812, about one-fourth of the Cherokee Nation east had emigrated to the Arkansas territory between the Arkansas and White Rivers. John Bowles, a chief, and a large number from Running Water Town, on the Mussel Shoals of the Tennessee, had left in the year 1874 and emigrated to the St. Francis River country in southeast Missouri. During the winter of 1811-12 this branch moved to the Arkansas Territory, where they were domiciled until a survey of the Cherokee Nation, Arkansas was made by the United States Government in 1816 in accordance with the provisions of the Treaty of 1817.

Cherokee Emigration to Texas

Bowles’ village was located between Shoal and Petit Jean Creeks, on the south side of Arkansas River, outside of the stipulated Cherokee Territory, on account of this fact and in compliance with the wishes of his followers to locate in Spanish territory, he, with sixty families, migrated in the winter of 1819-20 to territory that was claimed to have been promised them by the representatives of the Dominion of Spain, on Sabine River and extending from the Angelina to the Trinity Rivers in the Province of Texas.

Settlement was made north of Nacogdoches, then an expanse of waste and ruin, the result of warfare waged between the American and Spanish forces of Long and Perez. The climatic conditions auguring favorable to the pursuits of agriculture, stock-raising and hunting, their numbers were augmented occasionally by recruits from their brethren in Arkansas and other tribes of Indians in the United States.

For one whole year the Cherokees lived in peace and happiness under the roof of the hospitable Spaniard. Whether title to the lands accorded to and occupied by them was by prescription rights, the Indian mode of occupancy or in fee from the Monarch of Spain, is immaterial — they were there: their rights undisputed, under the impression they had a perfected right.

The Mexicans, their authority emanating from the imperial government at Mexico City, becoming dissatisfied with Spanish suzerainty over this portion of Latin America, adopted drastic measures toward throwing oft the Spanish yoke.

By the Plan of Iguala, adopted by the revolutionary government of Mexico, 24th February, 1821, the Mexicans published to the world that “all inhabitants of New Spain, without distinction, whether Europeans, Africans or Indians, are citizens of the monarchy, with a right to be employed in any post, according to their merit and virtues”, and that “The person and property of every citizen will be respected and protected by the government” The” Treaty of Cordova, of the 24th August, 1821, and the Declaration of Independence of the 28th September, 1821, reaffirmed the principles of the Plan of Iguala. Also the decree of the 9th April, 1823, which reaffirmed the three guaranties of the Plan of Iguala, viz:

- Independence;

- The Catholic religion;

- Union of all Mexicans of whatever race.

The decree of the 17th September 1822, with a view to give effect to the 12th Article of the Plan of Iguala, declared that classification of the inhabitants with regard to their origin, shall be omitted. The foregoing solemn declarations of the political power of the government, had the affect, necessarily, of investing the Indians with the full privileges of citizenship — as effectually as had the Declaration of Independence of the United States of 1776 of investing all those persons with these privileges, residing in the country .at the time.

Under the constitution and laws of Mexico, as a race, no distinction was made between the Indians, as to rights of citizenship and the privileges belonging to it and those of European or Spanish blood. The Mexican Republic from the time of its emancipation from Spain, always dealt most liberally with foreigners, in its anxiety to colonize its vacant lands. Where the grant declared that a citizen of the United States had been naturalized, it was taken for true. Thus, it will be seen during this transitory period in the political affairs of the country, the Cherokees bore the status of full fledged citizens of the Republic of Mexico, with all the privileges and immunities attached to the other inhabitants thereof. The first evidence of any attempt at acquiring legal title to the lands so occupied since their advent, is adduced by a letter from Richard Fields to James Dill-Alcalde of Nacogdoches, as follows:

“February 1st, 1822.

Dear Sir: I wish to fall at your feet and humbly ask you what must be done with us poor Indians. We have some grants that were given us when we lived under Spanish Government, and we wish you to send us news by the next mail whether they will be reversed or not. And if we were permitted, we will come as soon as possible to present ourselves before you in a manner agreeable to our talents. If we present ourselves in a rough manner, we pray you to right us. Our intentions are good toward the government.

Yours as a Chief of the Cherokee Nation,

Richard Fields

It appears that this communication went unanswered but was forwarded to the Governor of the Province of Texas at Bexar or San Antonio.

An indisputable title or unquestioned right of occupancy was desired on their part. With this object in view, a delegation repaired to Bexar and on the 8th November 1822, an agreement was entered into between the Cherokees and Jose Felix Trespalacios, Governor of the Province and acting for the Republic of Mexico.

“Articles of Agreement, made and entered into between Captain Richard (Fields) of the Cherokee Nation, and the Governor of the Province of Texas.

“ARTICLE 1. That the said Captain Richard (Fields) with five others of his tribe, accompanied by Mr. Antonio Mexia and Antonio Wolfe, who act as interpreters, may proceed to Mexico, to treat with his Imperial Majesty, relative to the settlement which said Chief wishes to make for those of his tribe who are already in the territory of Texas, and also for those who are in the United States.

“ART. 2nd. That the other Indians in the city, and who do not ac-company the before mentioned, will return to their village in the vicinity of Nacogdoches, and communicate to those who are at said village, the terms of this agreement.

“ART. 3rd. That a party of warriors of said village must be constantly kept on the road leading from the province to the United States, to prevent stolen animals from being carried thither and to apprehend and punish those evil disposed foreigners, who form assemblages, and abound on the banks of the River Sabine within the territory of Texas.

“ART. 4th. That the Indians who return to their town, will appoint as their chief, the Indian Captain called Kunetand, alias Tong Turqui to whom a copy of this agreement will be given, for the satisfaction of those of his tribe, and in order that they may fulfill its stipulations.

ART. 5th. That meanwhile, and until the approval of the Supreme Government is obtained, they may cultivate their lands and sow their crops in free and peaceful possession.

“ART. 6th. That the said Cherokee Indians will become immediately subject to the laws of the Empire, as well as others who tread her soil and they will also take up arms in defense of the nation, if called upon to do so.

“ART. 7th. That they shall be considered Hispano-Americans and entitled to all the rights and privileges granted to such, and to the same protection, should it become necessary.

“ART. 8th. That they can immediately commence trade with the other inhabitants of the province, and with the exception of arms and ammunitions of war, with the tribes of savages who may be friendly with us.

“Which agreement, comprising the eight preceding articles, has been executed in the presence of twenty-two Cherokee Indians of the Baron de Bastrop, who has been pleased to act as interpreter, of two of the Ayunta-miento, and two officers of this Garrison.

Bexar, 8th November 1822.

Jose Felix Trespalacios, Jose Flores, Nabor Villarreal, Richard Fields, x his mark, El Baron de Bastrop, Manuel Iturri Castillo, Franco de Castanedo.” In pursuance of this agreement Governor Trespalacios addressed the following communication to Don Caspar Lopez Commandant of the Eastern Internal Provinces, sending it by Lieutenant Don Ignacio Ronquillo:

“Captain Richard (Fields) of the Cherokee Nation, with twenty-two more Indians that accompanied him, visited me to ask permission for all belonging to his tribe, to settle upon the lands of this province. After I had been informed myself through foreigners, who are acquainted with this Nation, that it is the most industrious and useful of the tribes in the United States, I entered with said Captain, into an agreement, the original of which I send you. This arrangement provided that Captain Richard and six others of his nation, with two interpreters, escorted by Lieutenant Don Ignacio Ronquillo and fifteen men of the Visscayan, shall proceed to your headquarters and, if it meet your approval, thence to the court of the Empire.

“The Cherokee Nation, according to their statement, numbers fifteen thousand souls; but there are within the borders of Texas only one hundred warriors and two hundred women and children. They work for their living, and dress in cotton-cloth, which they themselves manufacture. They raise cattle and horses and use firearms. Many of them understand the English language. In my opinion, they ought to be useful to the Province, for they immediately became subject to its laws, and I believe will succeed in putting a stop to carrying stolen animals to the United States, and in arresting those evil-doers that infest the roads.”

From the foregoing agreement and communication, it will be seen that the matter of procuring title was only partially and temporarily realized. While occupation or prescription rights were accorded by the authorities, they were also recognized as Hispano-Americans and were clothed with judicial as well as police powers, pledging their unqualified support in time of war. They were reorganized as agriculturists, manufacturers and stock-raisers and were to apprehend and try offenders against the laws of the Empire.

Not being satisfied with conditions as to land titles, it was their determination to push their claims for a more satisfactory arrangement. Repairing to Saltillo headquarters of the Commandant General, they were sent, early in December on their way to Mexico City, where they arrived in the Spring of 1823. The conditions of the country were chaotic. The throne of Emperor Iturbide toppled and he was succeeded by Victoria, Bravo and Negrete on March 30th 1823, who held the reigns of government, exercising a joint regency.

During the progress of affairs. Fields and his fellow companions were detained, awaiting the decision of the government. The Minister of Relations gave notice that the agreement entered into between Fields and Trespalacios would be recognized, pending the passage of a general colonization law. The Minister of Relations. Lucas Alaman, in the new provisional government, wrote to Don Felipe de la Garza, the successor of Lopez, as Commandant General of the Eastern Internal Provinces, as follows:

“The Supreme Executive Power has been pleased to resolve that Richard Fields, Chief of the Cherokee Tribe of Indians, and his companions, now in this Capitol, may return to their country, and that they be supplied with what-ever may be necessary for that purpose. Therefore, Their Supreme High-nesses have directed me to inform you that, although the agreement made on the 8th November 1822, between Richard Fields and Colonel Felix Trespalacious. Governor of Texas, remains provisionally in force, you are nevertheless required to he very careful and vigilant in regard to their settlements endeavoring to bring them towards the interior, and at places least dangerous, not permitting for the present, the entrance of any new families of the Cherokee tribe, until the publication of the General Colonization Law, which will establish the rules and regulations to be observed, although the benefits to arise from it, cannot be extended to them, in relation to all of which. Their Highnesses intent to consult the Sovereign Congress. That while this is effecting, the families already settled, should be well treated, and the other chiefs also, treated with suitable consideration, provided that those already within our territory respect our laws, and are submissive to our authorities; and, finally, Their Highnesses order, that in future neither these Indians, nor any others, he permitted to come to the City of Mexico, but only send their petitions in ample form, for journeys similar to the present are of no benefit and only create unnecessary expense to the state. All of which I communicate to you for your information and fulfillment.”

That the delegation regarded their land titles secure is apparent. They returned home seemingly satisfied with their accomplishments. Victoria, Bravo and Negrete, through their Minister of Relations had confirmed the then existing contract until such time that a general colonization law was enacted, implying that titles would be more securely vested under such a law.

About a year later, Fields proposed a union of all the Indian tribes in Eastern Texas, proposing to exact a pledge from them, of fidelity to the government. In promulgating this, he gave a summary of his accomplishments in Mexico City and of his plans for the future. On March 6th, 1824, he wrote to the Governor at San Antonio, as follows:

“It was my intention, on my return from Mexico, to present myself at San Antonio, in order that the authorities there might examine the papers which I received from the Superior Government of the Nation: but it was impossible to do so because a party of Comanches had prepared an ambush on the road. However, I had the good fortune to escape them.

“The Superior Government has granted me in this province, a territory sufficient for me and that part of the tribe of Indians dependent on me to settle on, and also a commission to command all the Indian tribes and nations that are in the four eastern provinces.

“I pray your honor to notify all the Indians within your territory, and particularly the Lipans, that on the 4th of July next, I shall, in compliance with the order of the Supreme Government, hold a general council of all the Indian tribes, at my house in the Rancheria of the Cherokees twelve miles west of the Sabine River. At this Council I shall propose a treaty of peace to all Indians who are willing to submit themselves to the orders of the Government. In case there should be any who may not wish to ratify what I propose, I shall use force of arms to subdue them.

“I beg you to notify the commandant at San Antonio that he shall, for the satisfaction of his people, send some trusted person to aid in the treaty of peace and see how the affair is managed.

“Should it be convenient, have this letter translated and have the authorities send it to Rio Grande and Monclova, in which two places I left copies of the documents from the Superior Government.”

The Grand Council took place in pursuance of call, with exception of the date, which was changed to August 20th, 1824. All the tribes convened in council at Fields’ residence, with the exception of the Comanches and Tonkawas, on whom he proposed to make war.

Closely following these events the 24th January 1823, the Central Government under Augustine — the first constituted Emperor of Mexico enacted the Imperial Colonization Law of 1823, which decreed, among other things “that the Mexican Government will protect the liberty, property and civil rights of all foreigners, etc.” This was followed by the National Colonization Law of August 18, 1824 in which it was decreed, “To all who shall see and understand these presents, That the Mexican Nation offers to foreigners, who came to establish themselves within its territory, security for their persons and property, provided, they subject themselves to the laws of the country, etc. “and for this purpose, the legislatures of all the states will, as soon as possible, form colonization laws, or regulations for their respective states, conforming themselves in all things to the constitutional act-general constitution, and the regulations established in this law, etc.”

In pursuance of the foregoing, the State of Coahuila and Texas passed a colonization law March 25th. 1825, the first article of which reads:

“All foreigners who, in virtue of the general law of the 18th of August, 1824, which guarantees the security of their persons and property in this republic, shall wish to emigrate to any of the settlements of the State of Coahuila and Texas, are permitted to do so; and the said state invites and calls them.” Second. “Those who shall thus emigrate, far from being molested, shall be admitted by the local authorities of said settlements, and permitted by the same to freely engage in any honest pursuit, provided they respect the general laws of the republic, and the laws of the state.”

It is noticeable that the provisions of the three consecutive colonization laws, the word “foreigners” and the phrase “those who shall thus emigrate” would apply to those who arrived after their passage, the first the Imperial; decreed the 4th of January, 1823. For the sake of clearness, it is deemed advisable to reiterate that the Cherokees were Mexican citizens and had been prior to the passage of these laws, as much so as any others who emigrated to Texas and were so made by statute or constitutional enactment.

Possibly, owing to the absence of the locomotive, telegraph and other modes of travel and conveniences of communication, many of the early settlers of Texas did not know of the passage of these laws, or whether the vested rights of the Cherokees were purposely ignored on the part of the authorities of Coahuila and Texas, sitting at Saltilla, made divers and sundries grants of lands. These embraced portions of Cherokee territory, and among the donors were David G. Burnet, Vincente Filisola, Robert Leftwich, Frost Thorn and the Edwards Brothers. This act so incensed the Cherokees, that a council was soon after convened. Peter Ellis Bean reported to Stephen F. Austin that Fields addressed the council substantially as follows:

“In my old days, I traveled two thousand miles to the City of Mexico to beg some lands to settle a poor orphan tribe of Red People, who looked to me for protection. I was promised lands for them after staying one year in Mexico and spending all I had. I then came to my people and waited two years, and then sent Mr. Hunter, after selling my stock to provide him money for his expenses. When he got there, he stated his mission to the Government. They said they knew nothing of this Richard Fields and treated him with contempt.

“I am a Red man and a man of honor and can’t be imposed on this way. We will lift up our tomahawks and fight for land with all those friendly tribes that wish land also. If I am beaten, I will resign to fate, and if not, I will hold lands by the force of my red warriors.”

John Dunn Hunter, a White man. had come among the Cherokees sometime during the year 1825. Through his intervention, hope was held out that the agitated question of land title would be amicably settled. With this end in view, he was dispatched to Mexico City to plead their cause. He arrived at the seat of government March 19th, 1826 and returned in September, after fruitless attempts at a settlement of title.

Seeing their lands taken possession of by newcomers, their homes and firesides so long established, what they considered wrongfully wrested from them, they began to prepare to maintain their holdings peacefully if possible, but by force, if they must. Touching these events, Stephen F. Austin wrote the Commander of Texas September 11, 1826 in part, as follows:

“There is reason to fear that the delay of the measures concerning the peaceable tribes, has disgusted them; and should this be the case, it would be a misfortune, for 100 of the Cherokees are worth more as warriors than 500 Comanches. “

Hunter, “pictured in story and glowing language the gloomy alternative, now plainly presented to the Indians, of abandoning their present abodes and returning within the limits of the United States, or preparing to defend themselves against the whole power of the Mexican Government by force of arms.”

John G. Purnell wrote to Fields from Saltillo on October 4th, 1825, as follows:

“When I last saw you in my house at Monterey, I little thought in so short a time you would have commenced a war against your American brothers and the Mexican Nation; more particularly a man like yourself who is acquainted with the advantages of civilization. If your claims for lands were not granted at a time when the government was not firmly established, that should not be a cause of war. Ask and it will be given to you; this nation has always felt friendly inclined toward yours, and I am sure if you cease hostilities they will enter into a treaty with you by which you will obtain more permanent advantages than you can by being at war “.

On November 10th 1825, F. Durcy also of Saltillo, wrote to Francis Grapp a well-known Indian trader at Natchitoches:

“Knowing the weight of your influence with all the savage nations and also the ascendancy that you have over the character of Mr. Fields, your son-in-law, I think that no one could stop, better than yourself, the great disturbance which is about to be raised by the Indians, whom you understand better than I. I say that you can distinguish yourself for the welfare of humanity in general, in making the savages understand the evils which await them in “following the plans of Mr. Fields, and likewise causing Mr. Fields to be spoken to by his brother, who can prevail upon him (le determiner) to abandon a plan which will have no other end than that of destroying him-self and all who shall have the misfortune to follow him.”

Fredonian Rebellion

Hunter’s mission to Mexico City failed of its purpose. The Edwards brothers, who had been granted territory on which to settle eight hundred families, discovered that their claims of title conflicted with others originating under the Spanish regime. These lands also over-lapped the Cherokee session. They had consumed large sums of money, time and enormous amount of work in the United States arranging for the introduction of the eight hundred families called for by the terms of the empresario contract with the Mexican government. Finding themselves in dispute over their lands, almost the same as their neighbors, the Cherokees’ affairs were rapidly reaching a critical stage in that portion of Texas.

The Edwardses, highly incensed at the prospects of losing their all at one fell swoop, determined to throw off Mexican sovereignty and thus declare Texas a free and independent nation, under the name of the Republic of Fredonia.

Fields and Hunter concluded to confer with this embryo government on future plans. On their arrival at Nacogdoches, they found all excitement and chaos. A compact was entered into by Fields and Hunter, on the part of the Native Americans, Harmon B. Mayo and Benjamin W. Edwards, as agents of the Committee of Independence, culminating into a Solemn Union League and Confederation in peace and war to establish and defend their independence against Mexico.

The compact entered into, follows:

“Whereas, The Government of the Mexican United States, have, by repeated insults, treachery and oppression, reduced the White and Red emigrants from the United States of North America, now living in the Province of Texas, within the territory of said government, which they have been deluded by promises solemnly made, and most basely broken, to the dreadful alternative of either submitting their free-born necks to the yoke of the imbecile, unfaithful, and despotic government, miscalled a Republic, or of taking up arms in defense of their inalienable rights and asserting their independence; they- viz: The White emigrants now assembled in the town of Nacogdoches, around the independent standard, on the one part, and the Red emigrants who have espoused the same Holy Cause, on the other, in order to prosecute more speedily and effectually the war of Independence, they have mutually under-taken, to a successful issue, and to bind themselves by the ligaments of reciprocal interests and obligations, have resolved to form a treaty of Union, League and Confederation.

“For this illustrious object, Benjamin W. Edwards and Harmon B. Mayo. Agents of the Committee of Independence, and Richard Fields and John D. Hunter, the agents of the Red people, being respectfully furnished with due powers, have agreed to the following articles:

“1 The above named contracting parties, bind themselves to a solemn union, League, and Confederation, in peace and war, to establish and defend their mutual independence of the Mexican United States.

“2. The contracting parties guarantee mutually to the extent of their power, the integrity of their respective territories as now agreed upon and described viz: The territory apportioned to the Red people, shall begin at the Sandy Spring, where Bradley’s road takes off from the road leading from Nacogdoches to the Plantation of Joseph Dust; from thence west by the compass, without regard to variation, to the Rio Grande; thence to the head of the Rio Grande; thence with the mountains to the head of the Big Red River; thence north to the boundary of the United States of America; thence with the same line to the mouth of Sulphur Fork; thence in a right line to the beginning.

“The territory apportioned to the White people, shall comprehend all the residue of the Province of Texas, and of such other portions of the Mexican United States, as the contracting parties, by their mutual efforts and resources, may render independent, provided the same shall not extend further west than the Rio Grande.

“3. The contracting parties mutually guarantee the rights of Empresarios to their premium lands only, and the rights of all other individuals, acquired under the Mexican Government and relating or appertaining to the above described territory, provided the said Empresarios and individuals do not forfeit the same by an opposition to the independence of the said territories, or by withdrawing their aid and support to its accomplishment.

“4. It is distinctly understood by the contracting parties, that the territory apportioned to the Red people, is intended as well for the benefit of those tribes now settled in the territory apportioned to the White people, as for those living in the former territory, and that it is incumbent upon the contracting parties for the Red people to offer the said tribes a participation in the same.

“5. It is also mutually agreed by the contracting parties, that every individual. Red or White, who has made improvements within either of the Respective Allied Territories and lives upon the same, shall have a fee simple of a section of land, including his improvement, as well as the protection of the government in which he may reside.

“6. The” contracting parties mutually agree, that all roads, navigable streams, and all other channels of conveyance within each Territory, shall be open and free to the use of the inhabitants of the other.

“7. The contracting parties mutually stipulate that they will direct all their resources to the prosecution of the Heaven-inspired cause which has given birth to this solemn Union, League and Confederation, firmly relying upon their united efforts, and the strong arm of Heaven for success.

“In faith whereof, the Agents of the respective contracting parties hereunto affix their names.

“Done in the town of Nacogdoches, this the twenty-first of December, in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and twenty-six.”

Richard Fields,

John D. Hunter,

B. W. Edwards,

H. B. Mayor.

“We, the Committee of Independence, and the Committee of the Red people, do ratify the above Treaty, and do pledge ourselves to maintain it in good faith.

“Done on the day and date above mentioned.

Richard Fields,

John D. Hunter,

Ne-Ko-Lake,

John Bags,

Cuk-To-Keh,

Martin Parmer, President, Hayden Edwards, W. B. Legon, John Sprowl, B. J. Thompson, Jos. A. Huber, B. W. Edwards, H. B. Mayo.

Austin’s Colony

While these things were transpiring in and around Nacogdoches, the Mexicans, with their chief allies Stephen F. Austin and Peter Ellis Bean, were stirring up dissatisfaction among the Fredonians, both Native and White people. To forestall any further preparations on the part of the infant revolutionary government, Bent on 16th December, arrived with thirty-five Mexican soldiers from San Antonio. On learning of the feelings that pervaded the Fredonians, he retired to a point west of Nacogdoches to await reinforcements, realizing his forces were inadequate to successfully cope with the revolutionary forces. About the 20th of the same month, two hundred strong under Colonel Mateo Ahumada, with banners flying, the glittering of steel and the clanking of arms, marched out of San Antonio, bent on the conquest of Nacogdoches. This contingent was accompanied by Jose Antonio Saucedo, the Political Chief, in full charge of operations.

On January 22nd – 1826, Austin addressed the Mexican people in terms, as follows:

“To the Inhabitants of the Colony:

“The persons who were sent on from this colony by the Political Chief and Military Commandant (Austin) to offer peace to the madmen of Nacogdoches, have returned without having affected anything. The olive branch of peace which was held out to them has been insultingly returned, and that party have denounced massacre and desolation to this colony. They are trying to excite all the Northern Indians to murder and plunder, and it appears as though they have no other object than to ruin and plunder this country. They openly threaten us with massacre and the plunder of our property.

“To arms then, my friends and fellow citizens, and hasten to the standard of our country.

“The first hundred men will march on the 26th. Necessary orders for mustering and other purposes will be issued to commanding officers.

Union and Mexico.

S. F. Austin.

San Felipe de Austin, January 27th – 1827.”

The authorities and leading citizens of Austin’s Colony lost no time in fomenting dissension in the ranks of the Fredonians. From the capitol of his colony, Austin hurled all the epithets at his command against his liberty-loving American brothers. Writers of Texas history condemn him for the course taken in this instance. A careful perusal of the compact entered into by the Fredonians will not disclose an iota justifying his denunciations in such terms, in his proclamation to the colonists. The compact was to them, what the immortal document of 1776 was to the Americans during the gloomy days of the American Revolution. It was their divorcement from a weak, unstable and vacillating rule. It was the forerunner of the glory of San Jacnito, the climax that thrills the heart of every loyal Texan and freeman throughout Christendom. Doomed to failure it was, and the perpetrators suffered the consequences.

Their propaganda was successful. Promises of land and other pre-ferments by Bean and Austin detached large numbers of the Fredonians leaving the loyal, in a hopeless state. Bowles and Mush, of the Cherokees, were among the detached. Due to their machinations Fields and Hunter were foully murdered by men of their own people. The Edwards contingent was dispersed and fled to Louisiana, and other portions of the United States. For his services in having Fields and Hunter put out of the way. Bowles was invested with a commission as nominal Colonel in the Mexican army, as was also Peter Ellis Bean. The Fredonia affair was terminated.

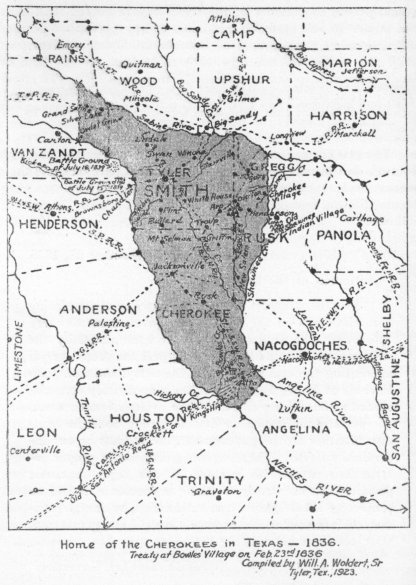

Home of the Cherokee in Texas

Affairs in this portion of Texas were restored to normalcy, with the exception of the mooted question of land titles. To further complicate matters, the legislature made a division of the territory in question between David G. Burnet and Joseph Vehlein.

The Act of April 6th, 1830, prohibiting the further emigration of Americans into Texas, was passed. General Teran Commandant General of the Eastern Interior States, determined to perfect title in the Cherokees, to lands so long occupied by them, and on August 15th, 1831 wrote to Letona, Governor of Coahuila and Texas:

“In compliance with the promises made by the Supreme Government, to the Cherokee Indians, and with a view to the preservation of peace, with the rude tribes, I caused them to determine upon some fixed spot for their settlement, and having selected it on the head waters of the Trinity, and the banks of the Sabine, I pray your Excellency may be pleased to order that possession be given to them, with the corresponding titles, with the understanding that it will be expedient, that the commissioners be appointed for this purpose, should act in conjunction with Colonel Jose de las Piedras, commanding the military forces on the frontier of Nacogdoches.”

Teran’s suggestions that title be consummated was universally concurred in by the authorities. March 22, 1832, Governor Letona ordered the political chief to furnish Commissioner Piedras with the necessary documents in due form for that purpose. On the eve of preparations to carry out such orders, he was expelled from Nacogdoches by an uprising of Americans. Soon afterwards, Teran committed suicide and was succeeded in office by Vincente Filisola who held an empresario contract in his own name. This appointment was detrimental to the interests of the Cherokees in the extreme, be-cause his contract embraced a portion of their lands. Governor Letona died of yellow fever and was succeeded by Beramendi.

The attempts on the part of Mexico to grant title, ended with these transactions.

On July 20th, 1833, a delegation headed by Colonel Bowles, repaired to San Antonio and petitioned the Political Chief for title to their lands. They were directed to Monclova, the Capitol of the Province of Coahuih and Texas, where they were given assurance that their claims would receive due consideration. But, inasmuch as David G. Burnet and Vincente Filisola had immature colonization contracts which were to expire December 21st 1835, all land title, he maintained, must, of necessity, be held in abeyance for the time being. However, on March 10th – 1835, the Political Chief wrote the Supreme Government, admonishing the authorities that the Cherokees be not disturbed in their possessions until the central government at Mexico City could finally pass on the question.

On May 12, 1835, the legislature of the state of Coahuila and Texas passed the following resolution:

“Art. 1. In order to secure the peace and tranquility of the state, the government is authorized to select, out of the vacant lands of Texas, that land which may appear most appropriate for the location of the peaceable and civilized Indians which may have been introduced into Texas.

“Art. 2. It shall establish with them a line of defense along the frontier to secure the state against the incursions of barbarous tribes.”

This was the last utterance of the Mexican government in reference to the Cherokee claims.

At the beginning of the disaffection of the Americans, the Committee of Public Safety, the Permanent Council and Consultation, successively, had deemed it just and prudent to arrive at some understanding with the Cherokees and other Indians concerning their land claims.

The state of affairs at this period existing between the Central Government at Mexico City and the State of Coahuila and Texas was exceedingly critical. On the 19th of September, 1835, on behalf of the Committee of Safety, Stephen F. Austin addressed the people of Texas in part: “That every district should send members to the General Consultation, with full powers to do whatever may be necessary for the good of the country.”

The General Consultation convened on the l6th October 1835, but adjourned for want of a quorum. It reassembled at San Felipe de Austin on November 1st, but was unable to dispatch business until the 3rd, when a quorum appeared. Dr. Branch T. Archer of Brazoria, formerly Speaker of the House of Delegates in the Virginia Legislature, was unanimously elected President. This was the third deliberative body authorized on the American plan, superseding the conventions of October 1, 1832, and April 1, 1833. In an elaborate speech to the convention, President Archer reviewed the condition of affairs of the country and recommended plans upon which Texas was to erect autonomy and at the same time contest upon the field of battle for a long cherished independence. Among other things impressed upon the members of the Consultation, were the need of establishing a provisional Government, with a Governor, Lieutenant Governor and Council to be clothed with Legislative and executive powers; and that “there are several warlike and peaceful tribes of Indians that claim certain portions of our land. Locations have been made within the limits they claim, which has created great dissatisfaction amongst them. Some of the chiefs of those tribes are expected here in a few days, and I deem it expedient to make some equitable arrangement of the matter that will prove satisfactory to them.”

On the 7th of November 1835, the Unanimous Declaration of the Consultation was adopted. It declared that “General Lopez de Santa Anna and other military chieftains have, by force of arms overthrown the federal institutions of Mexico and dissolved the social compact which existed between Texas and other members of the Mexican Confederacy; Now the good people of Texas, availing themselves of their natural rights, Solemnly Declare 1st. That they have taken up arms in defense of their Rights and Liberties, “.

In pursuance of this Declaration of Independence, a Plan or Constitution for a Provisional Government was drawn by a committee headed by Henry Smith, reported to that body on November 9th, but was not adopted as the organic act until the 11th, at which time it was enrolled and signed. A provisional Government was thus created, among the prerogatives or duties imposed upon the Governor and Council were to hypothecate the public lands and pledge the public faith for a loan not to exceed one million dollars; to impose and regulate imports and tonnage duties and provide for the collection of the same; treat with the several tribes of Indians in reference to their land titles, and, if possible, to secure their friendship; establish post-offices and post-roads; regulate postal rates and appoint a post-master general; grant pardons and hear admiralty cases.

Adoption of this plan and the election of officers took place on November 12th, and signed by the fifty-four delegates present on the following day. Henry Smith, opposed by S. F. Austin, was duly elected Provisional Governor, while James W. Robinson of Nacogdoches was elected Lieutenant Governor.

From the time of the conception of a separation of Texas from Mexico, it was deemed advisable to conciliate the Indian tribes within her borders, and this could best be brought about by entering into a treaty of friendship and neutrality and at the same time guarantee to them title to the lands occupied. The Cherokees were peacefully domiciled in east central Texas and were regarded, and justly so, as agriculturists, manufacturers, stock-raisers and the following of other pursuits that well placed them out of the savage or hunter class and compelled the fitting appellation of Civilized Indians. They possessed, as a nation, several hundred soldiers or warriors who were expert riflemen.

On November 13th, 1835, the day of the adoption of the Plans and Powers of the Constitution of the Provisional Government, the following Solemn Declaration was unanimously adopted and signed by the entire body of fifty-four members:

“Be It Solemnly Decreed. That we the chosen delegates of the Consultation of the people of all Texas, in general convention assembled, solemnly declare that the Cherokee Indians, and their associate bands, twelve tribes in number, agreeable to their last general council in Texas, have derived their just claims to lands included within the bounds hereinafter mentioned from the government of Mexico, from whom we have also derived our rights to the soil by grant and occupancy.

“We solemnly declare that the boundaries of the claims of the said Indians to the land’ is as follows, to-wit: Lying north of the San Antonio road and the Neches, and west of the Angelina and Sabine Rivers. We solemnly declare that the Governor and General Council, immediately on its organization, shall appoint Commissioners to treat with the said Indians, to establish the definite boundaries of their territory and secure their confidence and friendship.

“We solemnly declare that we will guarantee to them the peaceful enjoyment of their rights to the lands, as we do our own; we solemnly declare, that all grants, surveys and locations of lands, hereinbefore mentioned, made after the settlements of said Indians, are, and of right ought to be, utterly null and void, and that the Commissioners issuing the same, be and are here-by ordered, immediately to recall and cancel the same, as having been made upon lands already appropriated by the Mexican Government.

“We solemnly declare that it is our sincere desire that the Cherokee Indians, and their associate bands, should remain our friends in peace and war, and if they do so, we pledge the public faith for the support of the foregoing declarations.

“We solemnly declare that they are entitled to our commiseration and protection, as the just owners of the soil, as an unfortunate race of people, that we wish to hold as friends, and treat with justice. Deeply and solemnity impressed with these sentiments as a mark of sincerity, your committee would respectfully recommend the adoption of the following resolution: “Resolved, That the members of this convention, now present, sign this Declaration, and pledge the public faith, on the part of the people of Texas. “Done in Convention at San Felipe de Austin, this 13th day of November, A. D., 1835.

(Signed) B. T. Archer, President,

John A. Wharton, Meriwether W. Smith, Sam Houston, William Menifee, Chas. Wilson, Wm. N. Sigler, James Hodges, Wm. W. Arrington, John Bevil, Wm. S. Fisher, Alex. Thompson, J. G. V. Pierson, D. C. Barrett. R. Jones Jesse Burnam, Lorenzo de Zavala, A. Horton, Edwin Waller, Daniel Parker, Wm. P. Harris. John S. D. Byrom, Wm. Whitaker, A. G. Perry. Albert G. Kellogg, C. C. Dyer, Geo. M. Patrick, J. D. Clements, Claiborne West, Jas. W. Parker, J. S. Lester, Geo. W. Davis, Joseph L. Hood, A. E. C. Johnson, Asa Hoxey, Martin Parmer, Asa Mitchell, L. H. Everett, R. M. Williamson, Phillip Coe. R. R. Royal. John W. Moore, Benj. Fuga, Sam T. Allen, Wyatt Hanks, James W. Robinson, Henry Millard, Jesse Grimes, A. B. Hardin, Wyly Martin, Henry Smith, David A. Macomb. A. Houston. E. Collard.

P. B. Dexter. Secretary.”

Pledging the public faith on the part of the people of Texas, among other things the “Solemn Declaration,” after defining the boundaries of the churns of the Cherokees enunciated “that we will guarantee to them the peaceful enjoyment of their rights to their lands, as we do our own, we solemnly declare that all grants, surveys and locations of lands, within the bounds here in before mentioned, made after the settlement of said Indians, are, and of right ought to be utterly null and void, and the commissioners issuing the same, be and are hereby ordered, immediately to recall and cancel the same, as having been made upon lands already appropriated by the Mexican Government. After the passage of the Colonization Laws. Giving to the respective states the right to make disposition of the vacant lands within their boundaries, it will be remembered that David G. Burnet and others were awarded contracts affecting lands within the boundaries described and partially in the Cherokee Nation.

When the consultation was published to the world, it was the just a little over a month until the date of the expiration of the contracts of Burnet and Fileasola, which fell on December 21, 1835 “And all grants, survey’s and locations of lands within the bounds here in before mentioned, made after the settlement of said Indians, are, and of right ought to be, null and void.”

As has been said, the Cherokees settled on these lands in the winter of 1819-20, while the contracts of Burnet bear date of December 22, 1826. All the acts of the Consultation were the basic or organic laws of the land and if any act is to be accepted as such, these contracts must certainly have been annulled, since their provisions bore directly upon lands already appropriated by the Mexican Government and so recognized by the Consultation and the Provisional Government of Texas. “Language could not be made more plainer or obligatory than was this guarantee to these tribes.”

Among the several acts of this body, a Major General who was to be Commander-in-chief of all the Military forces, was elected by that body. Sam Houston was the unanimous choice. His commission follows:

“In the name of the people of Texas free and sovereign.

“We, reposing special trust and confidence in your patriotism, valor, con-duct and fidelity, do by these presents constitute and appoint you to be Major General and Commander-in-chief of the armies of Texas and of all the forces now raised or to be raised by it and of all others who shall voluntarily offer their services and join the army, for the defense of the constitution and liberty, and for repelling every hostile invasion thereof; and you are hereby vested with full power and authority to act as you shall think best for the good and welfare of the service.

“And we do hereby strictly charge and require all officers and soldiers under your command to be obedient to your orders, and diligent in the exercise of their several duties.

“And we do also enjoin you to be careful in executing the great trust reposed in you, by causing strict discipline and order to be observed in the army and that the soldiers be duly exercised- and provided with all convenient necessaries.

“And you are to regulate your conduct in every respect by the rules and discipline of war adopted by the United States of North America or such as may be hereafter adopted by this government; and particularly to observe such orders and directions, from time to time, as you shall receive from this or a future government of Texas.

“This commission to continue in force until revoked by this or a future government.

Done at San Felipe de Austin, on the fourteenth day of November, eighteen hundred and thirty-five.

Henry Smith.

Governor.

P. B. Dexter, Secretary of Provisional Government.”

On November 14th, the Consultation ceased its labors. Governor Smith immediately convened the Council for the government of the country. Upon the organization of the Council, Governor Smith addressed that body the following letter relative to carrying into effect that portion of the Declaration touching the Cherokee claims:

“San Felipe, December, 18, 1835.

Gentlemen of the Council:

” __________ I further have to suggest to you the propriety of appointing the Commissioners on the part of this government to carry into effect the Indian treaty as contemplated by the Convention. I can see no difficulty, which can reasonably occur in the appointment of the proper agents on our part, having so many examples and precedents before us. The United States have universally sent their most distinguished military officers to per-form such duties, because the Indians generally look up to and respect their authority as coercive and paramount. 1 would therefore suggest the propriety of appointing General Houston, of the army, and Col. John Forbes of Nacogdoches, who has been already commissioned as one of my aides. The Commissioners would go specially instructed, so that no wrong could be committed either to the government, the Indians, or our individual citizens. All legitimate rights would be respected, and no others. I am aware that we have no right to transcend the superior order, and Declaration made by the convention, and, if I recollect that article right, the outline of external boundaries was demarked within which the Indian tribes alluded to, should be located; but at the same time paying due regard to the legitimate rights of the citizens within the same limits.

“If these Indians have introduced themselves in good faith under the Colonization Laws of the Government, they would be entitled to the benefit of these laws and comply with their conditions. I deem it a duty which we owe them to pay all due respects to their rights and claim their co-operation in the support of them and at the same time not to infringe upon the rights of our countrymen, so far as they have been justly founded.

“These agents going under proper instructions, would be enabled to do right, but not permitted to do wrong, as their negotiations would be subject to investigation and ratification by the government before they became a law.

I am, gentlemen.

Your Obedient Servant.

Henry Smith. Governor.”

Resolution Appointing Commissioners to Treat With the Cherokee Indians Etc.

“Be It Resolved by the General Council of the Provisional Government of Texas, That Sam Houston, John Forbes and John Cameron, be and they are hereby appointed Commissioners to treat with the Cherokee Indians, and their twelve Associated Bands, under such instructions as may be given them by the Governor and Council and should it so happen that all the Commissioners cannot attend, and two of them shall have power to conclude a treaty and report the same to the General Council of the Provisional Government, for its approval and ratification.

“Be It Further Resolved, etc. That said Commissioners be required to hold said treaty so soon as practicable.

“Passed Dec. 22d. 1835.

James W. Robinson, Lieut.-Gov. and ex-offlco Pres’t. of G. C.

E. M. Pease, Secy, to General Council,

Approved, December 28, 1835.

Henry Smith, Governor. C. B. Stewart,

Sec’y. to Executive.”

Resolution for Instructing Commissioners Appointed to Treat with the Cherokee Indians and Their Associate Bands:

“Be it resolved by the General Council of the Provisional Government of Texas- That Sam Houston, John Forbes and John Cameron, appointed Commissioners to treat with the aforesaid Indians, be and they are hereby instructed, to proceed as soon as practicable, to Nacogdoches, and hold a treaty with the Indians aforesaid, and that they shall in no wise transcend the Declarations made by the Consultation of November last, in any of their articles of treaty.

“Sec. 2. Be it Further Resolved, etc. That they are required In all things to pursue a course of justice and equity toward the Indians, and to protect all honest claims of the whites, agreeably to such laws, compacts or treaties, as the said Indians may have hereto made with the Republic of Mexico, and that the (said) Commissioners be instructed to provide in said treaty with the Indians, that they shall never alienate their lands, either separately or collectively, except to the Government of Texas, and to agree that the said Government will at any time hereafter, purchase all their claims at a fair price and reasonable valuation.

“Sec. 3. Be It Further Resolved, etc.. That the Governor be required to give to the Commissioners, such definite and particular instructions, as he may think necessary to carry into effect the object of the foregoing resolutions, together with such additional instructions as will secure the effective co-operation of the Indians at a time when it may be necessary to call all the effective forces of Texas, into the field, and agreeing for their services in a body for a specified time.

“Sec. 4. Be It Further Resolved, etc., That the Commissioners be authorized and empowered to exchange other lands within the limits of Texas, not otherwise appropriated in place of the lands claimed by said Cherokee Indians and their Associated Bands.

“Passed at San Felipe de Austin, Dec. 26, 1835.

James W. Robinson,

Lieut. Gov. and ex-ofticio Prest. of G. C.

Henry Smith, Governor.

E. M. Pease,

Sec’y. of General Council

C. B. Stewart, Sec’y. of Executive.

Treaty Between the Commissioners on Behalf of the Provisional Government of Texas and the Cherokee Indians and Twelve Associated Tribes:

“This treaty this day made and established between Sam Houston and John Forbes, Commissioners on the part of the Provisional Government of Texas, on the one part, and the Cherokees and their associate bands now residing in Texas, of the other part, to-wit: Shawness, Delawares, Kickapoos, Quopaws, Choctaws, Bouie, Jawanies, Alabomas, Cochaties, Caddoes of the Noches, Tahovcattokes, and Unatuquouous, by the head chiefs and head men and warriors of the Cherokees, as elder brothers and representatives of all other bands, agreeable to their last council. This treaty is made in conformity to the declaration made by the last general consultation at San Felipe and dated the I3th, of November, 1835.

“Article 1. The parties declare that there shall be a firm and lasting peace forever, and that friendly intercourse shall be preserved by the people belonging to both parties.

“Article 2. It is agreed and declared that the before-mentioned tribes or bands shall form one community and that they shall have and possess the lands within the following bounds, to-wit: Lying west of the San Antonio road and beginning on the west at the point where the road crosses the river Angelina and running up said river until it reaches the first large creek below the great Shawnee Village emptying into said river from the northwest; thence running with said creek to its main source, and from thence a due northwest course to the Sabine river, and with said river west, then starting where the San Antonio road crosses the Angelina river, and with the said road to n point where it crosses the Neches River, and thence running up to the east side of said river in a northwest direction.

“Article 4. It is agreed by all parties that the several bands or their tribes named in this treaty shall all remove within the limits or bounds as above described.

“Article 5. It is agreed and declared by the parties aforesaid that the land lying and being within the aforesaid limits, shall never be sold or alienated to any person or persons, power or government whatsoever other than the government of Texas, and the Commissioners on behalf of the Government of Texas, bind themselves to prevent in the future all persons from intruding on said bounds. And it is agreed on the part of the Cherokees, for themselves and their younger brothers, that no other tribes or bands of Indians whatsoever shall settle within the limits aforesaid, but those already named in this treaty and now residing- in Texas.

“Article 6. It is declared that no individual person, member of the tribes before named, shall have power to sell or lease land to any person or per-sons not a member or members of this community of Indians, nor shall any citizen of Texas be allowed to lease or buy land from any Indian or Indians.

“Article 7. That the Indians shall be governed by their own regulations and laws, within their own territory, not contrary to the laws of the Government of Texas. All property stolen from the citizens of Texas, or from the Indians shall be restored to the party from whom it was taken and the offender or offenders shall be punished by the party to whom he or they may belong.

“Article 8. The Government of Texas shall have power to regulate trade and intercourse, but no tax shall be laid on the trade of the Indians.

“Article 10. The parties to this treaty agree, that as soon as Jack Steel and Samuel Benge shall abandon their improvements without the limits of the before recited tract of country and remove within the same that they shall be valued and paid for by the Government of Texas the said Jack Steele and Samuel Benge having until the month of November, next succeeding from the date of this treaty, allowed them to remove within the limits before described. And all the lands and improvements now occupied by any of the before named bands or tribes not lying within the limits before described, shall belong to the Government of Texas and subject to its disposal.

“Article 11. The parties to this treaty agree, and stipulate that all the bands or tribes, as before recited (except Steele and Benge) shall remove within the before described limits within eight months from the date of this treaty.

“Article 12. The parties to this treaty agree that nothing herein contained shall effect the relations of the neighborhood thereof, until a General Council of the several bands shall take place and the pleasure of the convention of Texas be known.

“Article 13. It is also declared, That all the titles issued to lands not agreeable to the Declaration, of the General Consultation of the people of all Texas, dated the thirteenth day of November, eighteen hundred and thirty-five, within the before recited limits – are declared void as well as all orders and surveys made in relation to the same.

“Done at Colonel Bowl’s Village on the twenty-third day of February eighteen hundred and thirty-six, and the first year of the Provisional Government of Texas.

Signed:

Witness: Fox (his x mark) Fields, Henry Millard, Joseph Durst, A. Horton, George W. Case, Mathias A. Bingham, George V. Hockley, Sec’y. of Commission, Sam Houston, John Forbes, Colonel (his x mark) Bowl, Big (his x mark) Mush, Samuel (his x mark) Benge, Oozovta (his x mark), Corn (his x mark) Tassell.

The (his x mark) Egg, John Bowl, Tunnetee (his x mark).

Commissioners Sam Houston and John Forbes, on the part of the Provisional Government of Texas, reported as follows to the Governor:

Washington, February 29. 1836. To His Excellency, Henry Smith. Governor of Texas. Sir:

In accordance with a commission issued by your Excellency dated the 26th day of December 1835 the authorized commissioners, in the absence of John Cameron. Esquire, one of the commissioners named in the above mentioned instrument, most respectfully report: That after sufficient notice being given to the different tribes named in the commission, a treaty was held at the house of John, one of the tribe of Cherokee Indians

The Commissioners would also suggest to your Excellency that titles should be granted to such actual settlers as are now within the designated boundaries, and that they should receive a fair remuneration for their improvements and the expenses attendant upon the exchange in lands or other equivalent.

It will also be remembered by your Excellency that the surrender by the Government of the lands to which the Indians may have had any claims is nearly equivalent to that portion now allotted to them and we must respect-fully suggest that they should be especially appropriated for the use of the government. They also call your attention to the following remarks, viz: “The state of excitement in which the Indians were first found by your com-missioners, rendered it impossible to commence negotiations with them on the day set apart for it. On the day succeeding, the treaty was opened. Some difficulty then occurred relative to the exchange of lands, which the Commissioners proposed making for those now occupied by them, which was promptly rejected. The boundaries were those established as designated in the treaty alone and that such measures should be adopted by your Excellency for their security as may be deemed necessary _________ . The Commissioners used every exertion to retain that portion of territory for the use of the government, but an adherence to this would have but one effect, viz; that of defeating the treaty altogether.”

“Under these circumstances the arrangement was made as now reported in the accompanying treaty. They would also suggest the importance of the salt works to the government and the necessity that they should be kept for the use of the government.

‘The Commissioners also endeavored to enlist the chiefs of the different tribes in the cause of the people of Texas and suggested an enrollment of a force from them to act against our common enemy, in reply to which they informed us that the subject had not before been suggested to them, but a general council should be held in the course of the present month, when their determination will he made known.

“The expenses attendant upon the treaty are comparatively light, a statement of which will be furnished to your Excellency.

“All of which is most respectfully submitted.

John Forbes.”

Sam Houston

After about sixteen years the ambition of the Cherokees to acquire undisputed title to their lands were at last realized. Their boundaries were definitely established; they were in a national existence, holding their lands in community or in common, living under laws of their own making- executed by their own officers without outside interference, living under the protection of the Government of Texas with one or more agents among them.

Without doubt, the main issue between them and the Spanish and Mexican authorities was that the Cherokees desired their lands in common, which was their method in the United States, while this policy was unknown to the two regimes mentioned and contrary to the Caucasian method of conveying title. However, their settled claims were held in abeyance until finally settled under the terms of the “Solemn Declaration” of November 13, 1835 and the foregoing treaty.

Immediately following the submission of the treaty and report, General Sam Houston repaired to and took command of the army on March 11, 1836.

On March 1, the convention assembled and adopted the Declaration of Independence of Texas. On the following day, same was signed by the fifty-two members present; later six others appeared and signed, making the total fifty-eight. The arrival of Provisional Governor Smith, the Lieutenant Governor and the remnant of the Council and the submission of the following report by the Provisional Governor, marked the closing of the Provisional Government and the institution of a new order:

“To the President and Members of the Convention of the People of Texas

“Gentlemen: Called to the gubernational chair by your suffrages at the last Convention, I deem it a duty to lay before your honorable body a view, or outline of what has transpired since your last meeting, respecting the progress and administration of the government placed under my charge, as created and contemplated by the organic law.

“The Council, which was created to co-operate with me as the devisors of ways and means, having complied with all the duties assigned to them, by the third article of the Organic Law, was adjourned on the 9th of January last, until the 1st of the present month.

“The agents appointed by your body, to the United States, to contract a loan and perform the duties of agents generally, have been dispatched and are now actively employed in the discharge of their functions, in conformity with their instructions: and, while at the City of New Orleans, contracted a loan under certain stipulations, which together with their correspondence on that subject, are herewith submitted for your information

“_________Gen. Houston, Col. John Forbes and Dr. Cameron were commissioned on the part of this government to treat with the Cherokee Indians and their associate bands, in conformity with the Declaration of the Convention in November last, who have performed their labors as far as circumstances would permit, which is also submitted to the consideration of your body. Our naval preparations are in a state of forwardness. The schooners of war, Liberty and Invincible, have been placed under the command of efficient officers and are now on duty, and the schooners of war, In-dependence and Brutus, are daily expected on our coast from New Orleans, which will fill out our navy as contemplated by law. Our agents have also made arrangements for a steamboat, which may soon be expected, calculated to run between New Orleans and our seaports, and operate as circumstance-, shall direct. Arrangements have been made by law for the organization of the militia; but, with very few exceptions, returns have not been made as was contemplated, so that the plan resorted to seems to have proved ineffectual.

“The military department has been but partially organized- and for want of means, in a pecuniary point of view, the recruiting service has not progressed to any great extent, nor can it he expected ,until that embarrassment can be removed.

“Our volunteer army of the frontier has been kept under continual excitement and thrown into confusion owing to the improvident acts of the General Council by the infringements upon the prerogatives of the Commander-in-chief, by passing resolutions, ordinances, and making appointments, etc., which in their practical effect, were calculated in an eminent degree, to thwart everything like systematic organization in that department.

“The offices of auditor and controller of public accounts have some time since been created and filled, but what amount of claims have been passed against the government, 1 am not advised, as no report has yet been made to my office but of one thing I am certain, that many claims have been passed for which the government, in justice, should not be bound or chargeable. The General Council has tenaciously held on to a controlling power over the offices, and forced accounts through them contrary to justice and good faith, and for which evil I have never yet been able to find a remedy; and if such a state of things shall be continued long, the public debt will soon be increased to an amount beyond all reasonable conception.

“With a fervent and anxious desire that your deliberations may be fraught with that unity of feeling and harmony of action so desirable and necessary to quiet and settle the disturbed and distracted interests of the country, and that your final conclusions may answer the full expectations of the people at home and abroad,

“I subscribe myself with sentiments of the highest regard and consideration,

Your obedient servant,

Henry Smith, Governor.”

March 1, 1836.

“Executive Department Washington,

March 2nd, 1836.

Fellow-Citizens of Texas:

“The enemy are upon us. A strong force surrounds the walls of the Alamo, and threatens the garrison with the sword. Our country imperiously demands the service of every patriotic arm, and longer to continue in a state of apathy will be criminal. Citizens of Texas, descendants of Washington, awake! Arouse yourselves!

“The question is now to he decided, are we now to continue free men or bow beneath the rod of military despotism? Shall we, without a struggle, sacrifice our fortunes our liberties and our lives, or shall we imitate the ex-ample of our forefathers and hurl destruction on the heads of our oppressors? The eyes of the world are upon us. All friends of liberty and the rights of men are anxious spectators of our conflict, or are enlisted in our cause. Shall we disappoint their hopes and expectations? No! Let us at once fly to arms-march to the battlefield, meet the foe, and give renewed evidence to the world that the arms of freemen, uplifted in defense of liberty are right, are irresistible. Now is the day and now is the hour, when Texas expects every man to do his duty. Let us show ourselves worthy to be free, and we shall be free.

“Henry Smith, Governor.”

Lacking a quorum, the Council met from day to day only to adjourn, on the 11th, General Thos. J. Rusk of Nacogdoches introduced resolutions in the plenary convention, relieving the Governor and Council of the duties conferred upon them by the Consultation of November 3-14, 1835. It now became the duty of the convention to institute a new government.

The convention proceeded with utmost decorum until I6th when by special enactment a government ad interim was created for the republic until a regular government could be provided for. The ad interim government consisted of a President, Vice President and Cabinet. The President was clothed with all but dictatorial powers. On the I7th, a constitution for the republic was adopted and later submitted to the people for ratification or rejection. The convention elected the first President and Vice President.

The last day of the session fell upon March 18, 1836. The government ad interim elected as officers David G. Burnet, President, and for Vice President, Lorenzo de Zavala, the Mexican who espoused the cause of Texas. A full complement of officers was elected , including the re-election of Sam Houston, as Commander-in-chief. The labors of the convention ended on the 18th-and on the 21st moved to Harrisburg. Its members thereupon dispersed. Some joined the army while others made haste to reunite with their families to remove them to places of safety.

At the head of the Texas army stationed at Gonzales, General Houston wrote the following letter to Colonel Bowl, Chief of the Cherokee Nation under date April 13. 1836:

“My Friend Col. Bowl:

“I am busy and will only say, how da do, to you! You will get your land as it was promised in our treaty, and you, and all my Red brothers, may rest satisfied that I will always hold you by the hand, and look to you as Brothers and treat you as such!

“You must give my best compliments to my sister, and tell her that I have not worn out the moccasins which she made me; and I hope to see her and you and all my relatives, before they are worn out.

“Our army are all well, and in good spirits. In a little fight the other day several of the Mexicans were killed and none of our men hurt. Then are not many of the enemy in the country, and one of our ships took one of the enemy’s and took 300 barrels of flour, 250 kegs of powder and much property and sunk a big warship of the enemy, which had many guns.”

Texas Independence

The struggle for Texas Independence culminated in the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21st, 1836. With 783 Texans against the army of Mexico, commanded by the President and Dictator, Santa Anna with upwards of 1500 men. General Houston gained a decisive victory, capturing the President and dispersing his army.

While these things were transpiring, the Cherokees were living in quiet and peace on their land in East Texas where they had been domiciled for upwards of seventeen years. True to form, they had been reported to the Provisional Government-the Treaty of February 23, 1836. This treaty had been reported to the Provisional Government, as per instructions, on February 29th, 1836 by General Houston and John Forbes the commissioners. On March the 11th, the Governor Council surrendered all the official documents to the Convention. This treaty and report without doubt were among them. If the government did not avail itself of this opportunity to ratify the treaty, as was doubtless the purpose of the Consultation, there appears to be no record of it. However, the Texas Government and army were in a precarious state. The former was moved from place to place for convenience as well as safety, while the army was continually on the march eluding the strong Mexican army, headed by its President, was in pursuit.

The Neutrality, on the part of the Cherokees was sought and obtained at the outset. This was very essential at this stage of affairs and if it was ever the intention of the government to fail or refuse to ratify the treaty this could not be hazarded at this time.

Under the provisions of the constitution, the government ad interim passed out of existence. An election was held the first Monday in September 1836 for the purpose of electing a full set of officers. Sam Houston was chosen the first President of the New Republic, while Mirabeau B. Lamar was elected as Vice President. On October 2nd, they were inducted into office at Columbus, the seat of government.

In December 1836, the Cherokee Treaty was forwarded to the Senate for consideration. President Houston commenting in part, as follows:

“In considering this treaty you will doubtless bear in mind the very great necessity in conciliating the different tribes of Indians who inhabit portions of our country almost in the center of our settlements as well as those who extend along our border.”

No action was taken at this session. At the next session a committee was appointed to investigate the report. A report was made October 12, 1837, about ten months after its first submission to the senate, as follows:

“Resolved by the Senate of the Republic of Texas that they disapprove and utterly refuse to ratify the Treaty or any article thereof, concluded by Sam Houston and John Forbes on the 23rd day of February, 1836, between the Provisional Government of Texas of the one part and the “Head Chiefs,” Head Men and warriors of the Cherokees on the other part. Inasmuch as that said treaty was based on false promises that did not exist and that the operation of it would not only be detrimental to the interests of the Republic but would also be a violation of the vested rights of many citizens”

During his tenure of office as first President—General Houston made no further attempt to secure its ratification by the Senate. That the failure of the Texas Government to ratify rendered it invalid cannot be accepted as just. In summarizing, it will be seen that the provisions for its making were instituted and carried into effect by the Provisional Government. The same was reported to the Governor and Council and lay dormant during the existence of the government ad interim, but was finally resurrected and placed before the Senate in December 1836. No action was taken until October 12th, 1837, only to be rejected primarily on the grounds that the treaty “was based on promises that did not exist.” This took place during the fourth government of the country — while during the first it was necessary, under the then existing conditions, that the Cherokees be treated with and in the language of Provisional Governor Smith, “the commissioners would go specially instructed, so that no wrong could be committed, etc. ” If the “premises did not exist” it certainly must have been presumptuous for the government, at its very incipiency, to so assume an act. The “Solemn Declaration” was published to the world by the Consultation unsolicited by the Cherokees. The treaty commissioners appeared unheralded at the village of Bowles. Houston remarked in his report, “The state of excitement in which the Indians were first found by your Commissioners rendered it impossible to commence negotiations with them, etc. “

The “Solemn Declaration had been passed, adopted and signed by all of its fifty-four members unsolicited and unbeknown to them. The treaty negotiations were held and concluded on Cherokee soil. That the treaty should have received ratification seems to be the chief argument, especially for the present-day writers to expostulate in endeavoring to justify Texas for the expulsion of 1839.

In urging the Council to appoint Commissioners to treat with the Cherokees in conformity to the acts of the Consultation, Provisional Governor, Henry Smith said: “I can see no difficulty which can reasonably occur in the appointment of the proper agents on our part, having so many examples and precedents before us. The United States have universally sent their most distinguished military officers, etc. “

Very little had transpired in the eastern portion of Texas to disturb the tranquility of the Cherokees with the possible exception of Cordova, a Mexican military officer, who attempted to stir up a rebellion against Texas authority. Emissaries Miracle and Flores had been apprehended, and on their person were found dispatches for Mexico City, to the Cherokee authorities, soliciting their aid in a war to recover Texas. If these dispatches ever reached their destination, there is no record of it. Suffice to say if they did, they fell upon deaf ears, because the Cherokees did not attempt to espouse their cause. After a battle with the Kickapoos, General Rusk discovered the dead body of a Cherokee upon the battlefield and complained to Chief Bowles. The Chief answered his attempt to place any blame on his people by pointing out that the individual was a renegade member of his tribe and that whatever his acts, did not render them a national affair.

Notwithstanding, that, under Article Five of the treaty, the Texas Government bound itself “to prevent in future all persons from intruding within the said bounds.” and that such treaty was made in conformity to the “Solemn Declaration,” members of the Killough and Wilhouse families were alleged to have met death at the hands of unknown persons within the bounds of the Cherokee Nation. Col. Bowles immediately ordered the bodies delivered to the settlements without Cherokee territory, explaining that roving bands of prairie Indians were responsible for the deeds. The efforts of the Mexican representatives to procure the aid of the Cherokees and the murder of members of the Killough and Wilhouse families seem to constitute the entire grounds on the part of the Texas Government to remove them from their homes so long occupied but no legal cognizance was taken of them long before any Americans touched Texas soil in quest of a home where peace and happiness might be their lot.

She had obligated herself to perfect a survey of Cherokee territory. To carry this into effect President Houston, in the latter part of 1838, ordered Alexander Horton to make such survey. The south side, which is marked by the San Antonio road, was run, but it does not appear any further effort was made on the part of the government to complete the survey. However, suffice it to say the three remaining sides are natural demarcation, namely -The Angelina, Neches and Trinity rivers.

On October 27th, 1838, Col. Bowles wrote Horton, which is indicative of his attitude towards Texas, as follows: “Mr. Horton: