Muskogean Family, Muskogean Stock, Muskogean People, Muskogean Indians, Muskhogean Family, Muskhogean Stock, Muskhogean People, Muskhogean Indians. An important linguistic stock, comprising the Creeks, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and other tribes. The name is an adjectival form of Muskogee, properly Măskóki (pl. Maskokalgi or Muscogulgee). Its derivation has been attributed to an Algonquian term signifying ‘swamp’ or ‘open marshy land’, but this is almost certainly incorrect. The Muskogean tribes were confined chiefly to the Gulf states east of almost all of Mississippi and Alabama, and parts of Tennessee, Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina. According to a tradition held in common by most of their tribes, they had reached their historic seats from some starting point west of the Mississippi, usually placed, when localized at all, somewhere on the upper Red River. The greater part of the tribes of the stock are now on reservations in Oklahoma.

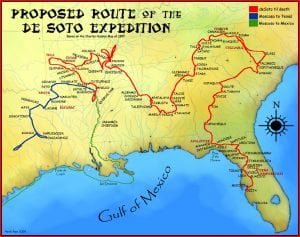

Through one or another of its tribes the stock early came into notice. Panfilo de Narvaez met the Apalachee of west Florida in 1528, and in 1540-41 De Soto passed east and west through the whole extent of the Muskogean Indian territory. Mission effort was begun among them by the Spanish Franciscans at a very early period, with such success that before the year 1700, besides several missions in lower Georgia, the whole Apalachee tribe, an important single body, was civilized and Christianized, and settled in 7 large and well-built towns. The establishment of the French at Mobile, Biloxi, and other points about 1699-1705 brought them into contact with the Choctaw and other western branches of the stock. The powerful Creek confederacy had its most intimate contact with the English of Carolina and Georgia, although a French fort was long established in the territory of the Alibamu. The Chickasaw also were allies of the English, while the Choctaw were uncertain friends of the French. The devotion of the Apalachee to the Spaniards resulted in the destruction of the former as a people at the hands of the English and their Indian allies in the first years of the 18th century. The tide of white settlement, both English and French, gradually pressed the Muskogean tribes back from the shores of the Atlantic and the Gulf, some bands recrossing to the west of the Mississippi as early as 1765. The terrible Creek War in 1813-14 and the long drawn-out Seminole War 20 years later closed the struggle to maintain themselves in their old territories, and before the year 1840 the last of the Muskogean tribes had been removed to their present location in Oklahoma, with the exception of a few hundred Seminole in Florida, a larger number of Choctaw in Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana, and a small forgotten Creek remnant in east Texas.

There existed between the tribes marked dissimilarities as to both physical and cultural characteristics. For instance, the Choctaw were rather thickset and heavy, while those farther east, as the Creeks, were taller but well-knit. All the tribes were agricultural and sedentary, occupying villages of substantially built houses. The towns near the tribal frontiers were usually palisaded, while those more remote from invasion were left unprotected. All were brave, but the Choctaw claimed to fight only in self-defense, while the Creeks, and more particularly the Chickasaw, were aggressive. The Creeks were properly a confederacy, with the Muskogee as the dominant partner, and including also in later years the alien Yuchi, the Natchez, and a part of the Shawnee. The Choctaw also formed a loose confederacy, including among others several broken tribes of alien stock.

Muskogean Indians Government

In their government the Muskogean Indian tribes appear to have made progress corresponding to their somewhat advanced culture in other respects. In the Creek government, which is better known than that of the other tribes of the family, the unit of t s he political as well as of ‘ the social structure was the clan, as if many Indian tribes, marriage being forbidden within the clan, and the children belonged to the clan of the mother. Each town ]fall its independent government, its council being a miniature of that of the confederacy; the town and its outlying settlements, if it had any, thus represented an autonomy such as is usually implied by the terra “tribe.” Every considerable town was provided with a “public square,” formed of 4 buildings of equal size facing the cardinal points, and each divided into 3 apartments. The structure on the east side was allotted to the chief councilors, probably of the administrative side of the government; that on the south side belonged to the warrior chiefs; that on the north to the inferior chiefs, while that on the west was used for the paraphernalia belonging to the ceremony of the black drink, war physic, etc. The general policy of the confederacy was guided by a council, composed of representatives from each town, who met annually, or as occasion required, at a time and place fixed by the chief, or head mice. The confederacy itself was a political organization founded on blood relationship, real or fictitious ; its chief object was mutual defense, and the power wielded by its council was purely advisory. The liberty within the bond that held the organization together was shown by the fact that parts of the confederacy, and even separate towns, might and actually did engage in war without reference to the wishes of the confederacy. The towns, especially those of the Creeks, were divided into two classes, the White or Peace towns, whose function pertained to the civil government, and the Red or War towns, whose officers assumed management of military affairs.

The square in the center of the town was devoted to the transaction of all public business and to public ceremonies. In it was situated the sweat house, the uses of which were more religious than medicinal in character; and here was the chunkey yard, devoted to the ball game from which it takes its popular name, and to the busk, or so-called green corn dance. Such games, though not strictly of religious significance, were affairs of public interest, and were attended by rites and ceremonies of a religious nature. In these squares strangers who had no relatives in the town – i. e., who possessed no clan rights – were permitted to encamp as the guests of the town.

The settlement of disputes and the punishment of crimes were left primarily to the members of the clans concerned; secondly, to the council of the town or tribe involved. The busk was important institution among the Muskogean people and had its analogue among most, if not all, other American tribes; itt was chiefly in the nature of an offering of first fruits, and its celebration, which occupied several days, was au occasion for dancing and ceremony; new fire was kindled by a priest, and from it were made all the fires in the town; all offenses, save that of murder, were forgiven at this festival, and a new year began. Artificial deformation of the head seems to have been practiced to some extent by all the tribes, but prevailed as a general custom among the Choctaw, who for this reason were sometimes called “Flatheads.”

The Muskogean population at the time of first contact with Europeans has been estimated at 50,000. By the census of 1890 the number of pure-bloods belonging to the family in Indian Territory was as follows: Choctaw, 9,996; Chickasaw, 3,464; Creek, 9,291; Seminole, 2,539; besides perhaps 1,000 more in Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. In 1905 their numbers were: Choctaw by blood, 17,160; by intermarriage, 1,467; freedmen, 5,254; in Mississippi, 1,235. Chickasaw by blood, 5,474; by intermarriage, 598; freedmen, 4,695. Creeks by blood, 10,185; freedmen, 5,738. Seminole by blood, 2,099; freedmen, 950; in Florida (1900), 358.

The recognized languages of the stock, so far as known, each with dialectic variants, are as follows:

- Muskogee (including almost half of the Creek confederacy, and its offshoot, the Seminole.

- Hitchiti (including a large part of the lower Creeks, the Mikasuki band of the Seminole, and perhaps the ancient Apalachee tribe).

- Koasati (including the Alibamu, Wetumpka, and Koasati towns of the Creek confederacy).

- Choctaw (including the Choctaw, Chickasaw, and the following small tribes: Acolapissa, Bayogoula, Chakchinnta, Chatot, Chula, Huma, Ibitoupa, Mobile. Mugalasha. Naniba. Ofogoula, Tangipahoa, Taposa, and Tohome).

To the above the Natchez should probably be added as a fifth division, though it differs more from the other dialects than any of these differ from one another. The ancient Yamasi of the Georgia-South Carolina coast may have constituted a separate group, or my have been a dialect of the Hitchiti. The Yamacraw were renegades from the lower Creek towns and in the main were probably Hitchiti.