With seven ships of his own providing, and accompanied by from six hundred to one thousand warlike and energetic adventurers, many of whom were of noble rank, Hernando De Soto set sail, in the month of April, 1538. Upwards of a year was spent, mostly upon the island of Cuba, before the fleet set sail for the Florida coast. In the latter part of May, 1539, the vessels came to anchor off the bay of Espiritu Santo, now Tampa Bay, on the western sea-board, and a large division of soldiers, both horse and foot, were landed. The Indians had taken the alarm, and, although the smoke of their fires had been seen from shipboard in various directions, all had fled from the district, or lay concealed in the thickets. De Soto appears to have been desirous to proceed upon peaceable terms with the natives, but hostilities soon followed. Some skirmishes took place near the point of landing, and the Spaniards speedily possessed themselves of the nearest village, where were the head-quarters of the cacique Ucita or Hiriga. Here De Soto established himself in “the lord’s house,” which was built upon a mound by the seashore; while the soldiers used the materials of the other buildings in constructing barracks.

At the inland extremity of the town stood the temple devoted by the Indians to religious observances. Over the entrance of this building was the wooden figure of a fowl, having the eyes gilded placed there for the purpose of ornament, or as symbolic of the tutelary deity of the place.

Clearings were now made around the village, to give free scope to the operations of the cavalry, and parties were sent out to explore the country, and to make prisoners who should serve as guides or hostages.

The remembrance of horrible outrages committed upon himself and his people by Narvaez, had so embittered the old chief Hiriga against the whites, that no professions of friendship and good will could appease his hatred. De Soto released prisoners who were taken by his scouting parties, charging them with presents and conciliatory messages for their chief, but all in vain.

In the tangled forests and marshes the Indians were found to be no contemptible opponents. They were described as being “so dexterous fierce and nimble that foot can gain no advantage upon them.” Their bows and arrows were so effective that coats of mail did not prove a sufficient protection against their force. The arrows were headed, as usual, with stone, or with fish-bones; those which were made of canes or reeds produced the deadliest effect.

A party under Gallegos, scouring the country a few miles from the camp, attacked a small body of Indians and put them to flight; but, as a horseman was charging with his lance at one of the number, he was amazed to hear him cry out, “Sirs, I am a Christian; do not kill me, nor these poor men, who have given me my life.”

Story of John Ortiz, A Spanish Captive Among The Indians

Naked, sunburned, and painted, this man was scarce distinguishable from his wild associates. His name was John Ortiz, and he had lived with the Indians twelve years, being one of the few followers of Narvaez who escaped destruction. Since the disastrous failure of that expedition he had made his way to Cuba in a small boat, and had returned again to Florida in a small vessel sent in quest of the lost party. The Indians enticed a few of the crew on shore, and made them prisoners. Ortiz was among the number, and was the only one who escaped immediate death. After amusing themselves by various expedients to terrify and torment their captive, the savages, by the command of their chief, Hiriga, bound him to four stakes, and kindled a fire beneath him. He was preserved, even in this extremity, by the compassionate entreaties and persuasions of a daughter of the cacique. His burns having been healed, he was deputed to keep watch over the temple where the bodies of the dead were deposited, to defend them from attacks of wolves. His vigilance and resolution, in dispatching a wolf, panther, or a “lion,” (according to one account) which had seized the body of a child of one of the principal chiefs, aroused a kindly feeling towards him, and he was well used for three years. At the end of that time Hiriga, having been worsted in fight with Moscoso, a hostile chief whose dwelling was at a distance of two days journey, thought it necessary or expedient to make a sacrifice of his Christian subject to the devil. “Seeing,” says our Portuguese historian, ” the devil holds these people in deplorable bondage, they are accustomed to offer to him the life and blood even of their subjects, or of any body else that falls into their hands.”

Forewarned of this danger by his former benefactress, Ortiz fled in the night towards the country of Moscoso. Upon first meeting with the subjects of this chief, he was in great danger from the want of an interpreter to explain whence he came, and what was his errand; but, at last, finding an Indian who understood the language of the people with whom he had lived, he quieted the suspicions of his hosts, and remained with them in friendship no less than nine years. Moscoso, hearing of the arrival of De Soto, generously furnished his captive with an escort, and gave him free permission to return to his countrymen, in accordance with a promise made when Ortiz first came to his territory.

The long-lost Spaniard was joyfully received, with his companions, at De Soto s camp; his services as guide being considered invaluable. In answer to the first inquiry, however, where gold was to be sought, he could give no satisfactory information.

The cacique Moscoso being sent for, soon presented him self at the Spanish encampment, and after spending some clays in familiar intercourse with the wonderful strangers, departed, exulting in the possession of a shirt and other tokens of royal munificence.

Progress Northward

“The long bare arms

Are heaved aloft, bows twang and arrows stream;

Each makes a tree his shield, and every tree

Sends forth its arrow. Fierce the fight and short

As is the whirlwind.” Bryant.

De Soto now concluded to send his vessels back to Cuba, and leaving a strong guard in Hiriga’s country, to proceed northward. Favorable accounts were brought by his emissaries from the adjoining district of Paracoxi, and deluding hopes of procuring gold invited to still more distant exploration in Gale. Vasco Porcalho, wearied and disgusted with hopeless and desultory skirmishing among the swamps and morasses, resigned his commission, and left with the squadron.

The Spanish force, proceeding up the country, passed with great difficulty the extensive morass now known as the Wahoo Swamp, and came to Gale in the southern portion of Alachua. The inhabitants of the town, which was large, and gave tokens of thrift and abundance, had fled into the woods, except a few stragglers who were taken prisoners. The troops fell upon the stored provisions, and ravaged the fields of maize with the eagerness of famished men.

Leaving Gale on the 11th of August, De Soto pressed forward to the populous town of Ochile. Here, without pretence of coming as friends, the soldiers fell upon the inhabitants, and overpowered them by the suddenness of their attack. The country was under the rule of three brothers, one of whom was taken prisoner in the town. The second brother came in afterwards upon the receipt of friendly messages from the Spanish general, but the elder, Vitachuco, gave the sternest and most haughty responses to all embassies proposing conciliatory measures. Appearing, at last, to be convinced by the persuasion of his two brothers, who were sent to him, he consented to a meeting. With a large company of chosen warriors, he proceeded to De Soto’s encampment, and, with due formality, entered into a league of friendship. Both armies be took themselves to the principal village of Vitachuco, and royal entertainment was prepared.

The treacherous cacique, notwithstanding these demonstrations, gathered an immense force of his subjects around the town, with a view of surprising and annihilating the Spaniards; but the vigilance of John Ortiz averted the catastrophe.

Preparations were at once made to anticipate the attack; and so successfully were they carried out, that the principal cacique was secured, and his army routed. Many of the fugitives were driven into a lake, where they concealed themselves by covering their heads with the leaves of water lilies. The lake was surrounded by the Spanish troops, but such was the resolution of the Indians, that they remained the whole night immersed in water, and, on the following day, when the rest had delivered themselves up, “being constrained by the sharpness of the cold that they endured in the water,” twelve still held out, resolving to die rather than surrender. Chilled and stupefied by the exposure, these were dragged ashore by some Indians of Paracoxi, belonging to De Soto’s party, who swam after them, and seized them by the hair.

Vitachuco

Although a prisoner, with his chief warriors reduced to the condition of servants, Vitachuco did not lay aside his daring purposes of revenge. He managed to circulate the order among his men, that on a day appointed, while the Spaniards were at dinner, every Indian should attack the one nearest him with whatever weapon came to hand.

When the time arrived, Vitachuco, who was seated at the general s table, rallying himself for a desperate effort, sprang upon his host, and endeavored to strangle him. ” This blade,” says the Portuguese narrator, ” fell upon the general; but before he could get his two hands to his throat, he gave him such a furious blow with his fist upon the face that he put him all in a gore of blood.” De Soto had doubtless perished by the unarmed hands of the muscular and determined chief, had not his attendants rushed to his rescue, and dispatched the assailant.

All the other prisoners followed their cacique s example. Catching at the Spaniards arms, or the “pounder where with they pounded the maize,” each set upon his master therewith, or on the first that fell into his hands. They made use of the lances or swords they met with, as skillfully as if they had been bred to it from their childhood; so that one of them, with sword in hand, made head against fifteen or twenty men in the open place, until he was killed by the governor’s halberdiers.” Another desperate warrior, with only a lance, kept possession of the room where the Indian corn was stored, and could not be dislodged. He was shot through an aperture in the roof. The Indians were at last overpowered, and all who had not perished in the struggle, were bound to stakes and put to death. Their executioners were the Indians of Paracoxi, who shot them with arrows.

Napetaca, the scene of this event, was left by the Spaniards in the latter part of September. Forcing their way through the vast swamps and over the deep and miry streams that intercepted their path, and exposed to the attacks of the revengeful proprietors of the soil, they came to the town of Uzachil, somewhere near the present Oscilla River, midway between the Suwanne and Appalachicola. Encumbered with horses, baggage, and armor as they were, their progress is surprising. Uzachil was deserted by the Indians, and the troops reveled in store of provision left by the unfortunate inhabitants.

Marauding parties of the Spaniards succeeded in seizing many prisoners, both men and women, who were chained by the neck, and loaded with baggage, when the army re commenced their march. The poor creatures resorted to every method to effect their escape; some filing their chains in two with flints, and others running away, when an opportunity offered, with the badge of slavery still attached to their necks. Those who failed in the attempt were cruelly punished.

The natives of this north-western portion of Florida evinced no little skill and good management in the construction of their dwellings and in their method of agriculture. The houses were pronounced “almost like the farm houses of Spain,” and some of the towns were quite populous.

Making a halt at Anhayca, the capital town of the district of Palache, De Soto sent a party to view the seacoast. The men commissioned for this service discovered tokens of the ill-fated expedition of Narvaez at Ante, where the five boats were built. These were a manger hewn from the trunk of a tree, and the bones of the horses who had been killed to supply the means of outfit.

De Soto, about the last of November, sent a detachment back to the bay of Espiritu Santo, with directions for two caravels to repair to Cuba, and the other vessels, which had not already been ordered home, to come round by sea and join him at Palache. Twenty Indian women were sent as a present to the general s wife, Donna Isabella.

In one of the scouting expeditions, during the stay at Palache, a remarkable instance of self-devotion was seen in two Indians, whom the troops came upon as they were gathering beans, with a woman, the wife of one of them, in their company. “Though they might have saved them selves, yet they chose rather to die than to abandon the woman.” “They wounded three horses; whereof one died,” before the Spaniards succeeded in destroying them.

Early in March 1540, the Spanish forces were put in motion for an expedition to Yupaha, far to the north-east. Gold was still the object of search. A young Indian, who was made prisoner at Napetaca, alleged that he had come from that country, and that it was of great extent and richness. He said that it was subject to a female cacique, and that the neighboring tribes paid her tribute in gold, “whereupon he described the manner how that gold was dug, how it was melted and refined, as if he had seen it done a hundred times, or as if the devil had taught him; inasmuch that all who understood the manner of working in the mines, averred that it was impossible for him to speak so exactly of it, without having seen the same.”

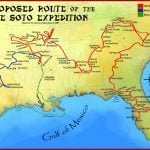

It would be foreign to our present subject to follow De Soto in this tour; and, indeed, the position of many of the localities which are described by his historians, and the distances and directions of his wearisome and perilous journeying, must, at the present day, be matters of conjecture. It may not, however, be amiss to mention briefly the accounts preserved of the appearance of some of the tribes through whose dominions he passed before his re turn to the north-western districts of modern Florida.

As he moved northward, a marked change was perceived in the buildings. Instead of the grass-covered huts, which served well enough in the genial climate of the peninsula, the people of Toalli had “for their roof little canes placed together like tile; they were very neat. Some had the walls made of poles, so artificially inter woven, that they seemed to be built of stone and lime.” They could be thoroughly warmed in the winter, which was there pretty severe. The dwellings of the caciques were roomy and commodious, and were rendered conspicuous by a balcony over the entrance. Great skill was shown by these people in the manufacture of cloth from grass or fibrous bark, and the deer skins, of which they made leggins and other articles, were admirably well dressed and dyed.

Expedition To Cutifachiqui

The most remarkable of the countries visited on this Northern exploration, was Cutifachiqui, supposed to have been situated far up the Chattahoochee, which was governed by a female. The Spaniards were astonished at the dignity and refinement of the queen. Her reception of De Soto reminds one of Cleopatra s first meeting with Anthony, as described by the great dramatist. She was brought down to the water in a palanquin, and there seated in the stern of a canoe, upon cushions and carpets, with a pavilion overhead. She brought presents of mantles and skins to the general, and hung a necklace of large pearls about his neck.

The Indians of the country were represented as ” tawny, well-shaped, and more polite than any before seen in Florida.” Their numbers had been greatly reduced, two years previous, by a pestilence, and many deserted dwellings were to be seen around the town. The accounts given of the quantity of pearls obtained here, by searching the places of sepulture, are incredible.

Departure For The West

Departing from Cutifachiqui, De Soto had the ingratitude to carry the queen along with him, compelling her even to go on foot. ” In the mean time, that she might deserve a little consideration to be had for her still,” she induced the Indians by whose houses the cavalcade passed, to join the party, and lend their aid in carrying the baggage. She succeeded, finally, in making her escape.

We must now dismiss De Soto and his band upon their long journey through the western wilderness. He died upon the Red River, and those of his companions who escaped death from exposure, disease, or savage weapons, years after the events above described, made their way down the Mississippi to the gulf, and thence reached the Spanish provinces of Mexico.