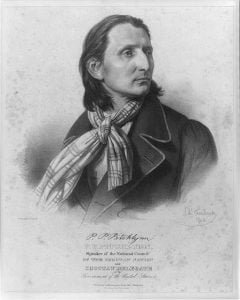

John Pitchlynn, the name of another white man who at an early day cast his lot among the Choctaws, not to be a curse but a true benefactor. He was contemporaneous with the three Folsom’s, Nathaniel, Ebenezer and Edmond; the three Nails, Henry, Adam and Edwin; the two Le Flores Lewis and Mitchel, and Lewis Durant. John Pitchlynn, as the others, married a Choctaw girl and thus become a bona-fide citizen of the Choctaw Nation. He was commissioned by Washington, as United States Interpreter for the Choctaws in 1786, in which capacity he served them long and faithfully. Whether he ever attained to the position of chief of the Choctaws is not now known. He, however, secured and held to the day of his death not only the respect, esteem and confidence of the Choctaws as a moral and good citizen, but also that of the missionaries who regarded him as one among their best friends and assistants in their arduous labors for the moral and religious elevation of the people of his adoption. He married Sophia Folsom, the daughter and only child of Ebenezer Folsom. They had five sons, Peter P., James, Thomas, Silas and Jack, all of whom were men of fine talents and high position, reflecting credit on their ancient and honorable name, except Jack, who was led astray and finally killed.

How many strange little incidents oft happen to various persons the cause of which none can satisfactorily explain; many of which are similar to the following that Major John Pitchlynn once experienced in early life! He stated to the missionaries that he, in company with sixty Choctaw warriors, was once returning home from a trading expedition to Mobile then a small town and trading point of the Choctaws. One night they all had lain down upon their blankets side by side, and all soon fell asleep but himself, who, by a strange and unusual restlessness, was unable to sleep. For a long time he rolled this way and that upon his blanket, but: all to no purpose; he could not sleep. Finally he arose, took up his blanket and lay down on the opposite side of the fire which had been made for the common benefit of the camp. Scarcely had he adjusted himself upon his new bed when a large tree suddenly fell to the ground and exactly across the bodies of his six sleeping comrades, killing every one of them, and leaving him a lone survivor of the camp. Major Pitchlynn often afterwards spoke of this incident as a manifestation of a special Providence; his unaccountable sleeplessness on that night, and his getting up and going to the other side of the fire to sleep, as a divine interposition in his special behalf. Peter was born January 30, 1806, in a little village called Shik-o-poh (The Plume), which was then in what is now Noxubee County. In early youth young Peter manifested a disposition for intellectual attainments; heat-tended the great councils of his Nation as an attentive hearer but silent spectator, and sought every opportunity to inform himself of all that was transpiring around him. As he grew up his desire to obtain an education increased, and he was finally sent to a school in Tennessee.

He returned home at a time his people were negotiating a treaty with the United States Government; when and where he made himself the object of much conversation, in the way of reproof by some, and commendation by others, in refusing to shake hands with Andrew Jackson, the negotiator of a treaty, which, in his youthful judgment, he regarded as an imposition (which Jackson himself well knew) upon his misled and deluded people and an insult to his Nation; this opinion was never changed to the hour of his death years after. After remaining at home awhile, he went to school at Columbia Academy, Tennessee; thence to the Nashville University, where he graduated; and afterwards became, as the sequel will show, a great and useful man to his Nation.

During his scholastic days at the Nashville University, General Jackson visited there officially as a trustee, and on seeing young Peter, at once recognized him as the Choctaw boy who had some years before refused to receive him as an acquaintance, or recognize in him a friend. Jackson, than whom few were better judges of human nature and moral worth, determined to win the friendship and confidence of the proud and manly young Choctaw, and succeeded finally in changing the old feeling of dislike to one of warm personal friendship, which sacred ties were never broken. After he graduated he returned home and settled, as a farmer, upon the outskirts of a beautiful prairie to which his name was given, and down to the war of 1861 it still bore, and perhaps does yet, the name, “The Pitchlynn Prairie.”

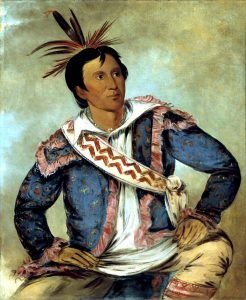

His remarkably manly form and bearing; his beautifully shaped head covered with long, black, shining hair and possessed with as black, piercing eyes as ever penetrated to the secret thoughts of the heart; his broad cheek-bones and brown complexion together with his natural and unaffected courteousness, affability and generous disposition, all served to constitute Peter P. Pitchlynn as stately and complete a gentleman of Nature s handy work as I ever beheld. He erected a comfortable house upon the spot selected for his home, and won the heart of the youngest daughter of Nathaniel Folsom, (Rhoda) to whom he was soon married ac cording to the usages of the Whites, by the missionary, Rev. Cyrus Kingsbury.

In 1824 a law was passed by the council of the Nation organizing a corps of Light-Horse (a little company of cavalry), who were clothed with the authority and also made as their imperative duty to close all the dram-shops that were dealing in the miserable traffic in opposition to law and treaty stipulations. The command of this band was given to young Peter P. Pitchlynn, who united the bravery of Leonidas to the incorruptible virtues of Aristides, and in one year, from the time he undertook to erase the foul blotch (traffic in whiskey) from the face of his country, he had successfully accomplished it.

From his soon known abilities he was early elected a member of the National Council, an honor never before conferred upon one so young. Pitchlynn at once brought be fore the council the necessity of educating their children, and argued the great advantages that would accrue there from; and, that the students might more readily become accustomed to the usages of the whites, he suggested the propriety of establishing a school for Choctaw youths in some one of the states. It was decided, therefore, by the council in accordance with his proposition, and a Choctaw Academy was established near Georgetown, Kentucky, sustained by the funds of the Nation, and stood, until driven from their ancient domains, a proud monument of the Choctaws advancing civilization under the fostering care of Gods missionaries sent to them.

In the year 1828 he, with another Choctaw, two Chickasaw and two Muskogee warriors, constituted a delegation appointed and sent by, and at the expense of, the United States Government, to go upon a peacemaking expedition into the Osage country west of the Mississippi river, now the State of Kansas, as the Osages and Choctaws were and had been uncompromising enemies for years untold; and if peace could be established between them, it was believed that the Choctaws would the more readily consent to the exchange of lands, as was afterwards made. The little band of six, few but resolute and fearless, with Pitchlynn as their chief,, went first to Memphis, then a little village; thence to St. Louis, where they received necessary supplies from the Indian superintendent; thence to Independence, consisting then of only a few log cabins, where they were received and hospitably entertained by a son of the renowned Daniel Boone. At Independence they were joined by an Indian agent; thence they started and made their first camp on a broad prairie near a Shawnee village. The Shawnees had never before seen a Choctaw, Chickasaw or Muskogee; nor had they ever seen a Shawnee, except in the persons of Tecumseh and his thirty warriors, in their memorable visit to their three nations in 1812, while each knew of the existence of the other. On the following morning Pitchlynn and his little band directed their footsteps toward the Shawnee village, with the decorations of the pipe of peace gaily fluttering to the prairie breeze above their heads an emblem ever respected and honored by the North American Indians any where and everywhere. Upon seeing the peace-pipe extended, the Shawnees at once came out to meet them, and escorted them in much pomp and ceremony into their village, where a council was soon convened to learn the object of the strangers visit; which soon being explained, pledges of friendship were exchanged and speeches made, and the strangers earnestly solicited to remain the next day to attend a grand feast that would be given to them in honor of their visit, which was duly accepted; and then the little band again took up its line of travel toward the territories of the Osages. For several days they traveled along on the famous Santa Fe Trail, then turned in a southeast direction, traveling over beautiful prairies skirted here and there with timber.

One day, about the middle of the afternoon, a few deer were seen on a prairie a half a mile distant, and Pitchlynn left his company to continue their course, while he would try to procure some venison for their supper. He had approached nearly near enough to risk a shot, when he was discovered by the deer, which scampered off across the prairie. At that moment he discovered a small herd of buffalo, at one of which he tried to get a shot; but they, too, discovered him and took to flight. He pursued them a mile or two, but finding- he was getting too far away he stopped his pursuit and turned to overtake his companions by traveling at an angle that would enable him to overtake or strike their trail several miles south of where he had left them. But after riding a few miles he saw about half a mile before him a ridge of undulating prairie, on the opposite side of which he felt sure his little company must have passed. As the sun was now hearing the western horizon, and he knew not how far his companions were ahead of him, he started for the top of the ridge in a brisk gallop until he reached the base of the hill, then reined in his horse to a steady walk as he ascended the ridge, ever keeping in practice the safe motto, “Caution is the mother of safety.” And well he did, for he was then in the country of Osages, who, not knowing his mission, would have made short work of him, had they have met him. As he drew nearer the top the slower he rode, and thus cautiously moved until he could see the valley beyond, and there he saw a company of Osage warriors but a short distance ahead. Some were riding slowly along intently looking on the ground, while others had dismounted and were leading their horses, now stooping with eager look and then pushing the grass this way and that, as if to find something lost. Pitchlynn at once comprehended the whole. They had found the trail of his companions and were using their woods-craft to read the signs indicated, and learn whether friends or foes had passed, and also their number.

Pitchlynn at once reined his horse backward until he was below the brow of the hill, then turned and rode slowly down until he had reached its base lest the sound of his horses feet should betray him; then struck off at full gal lop in a south direction and continued it until night called a halt. He then dismounted, roped his horse upon the grass, and lay down to reflect upon his days ventures, until sleep embraced him in her arms and lulled him to unconsciousness. In the morning he arose and was soon again on his dubious way, making a wide circuit to avoid running again upon his unwelcome neighbors. Again night overtook him a lone wanderer in a pathless wilderness, without having made any discoveries as to the whereabouts of his companions, or his enemies, the Osages. Again he stretched himself upon the grass and found forgetfulness in sleep. Again he started and was rejoiced, after an hours ride, to strike the trail of his friends whom he overtook in the evening of the same day. Not knowing what had become of him, or where to look for him in that endless wilderness, they had traveled slowly, hoping that he would yet come up; but when the second night came without his return, despair had usurped the place of hope and they had given him up as forever lost to them.

The Osages, for unknown reasons, did not pursue them. If, they had, there would have been a final separation as; the Osages so outnumbered them that not one of the little companies would have been left to tell the tale of their complete destruction. The unexpected return of their chief gave new life to all, and they pursued their journey with renewed vigor. In a few days they came to a large Osage village situated on a high bluff on the Osage river, and camped near the same, where they remained several days safe under the Pipe of Peace, whose decorations of ribbons fluttered above their camps; the Osages refusing, however, to meet them in council, since but a short time previous a war party of Choctaws had invaded their country, and in a battle had slain several of their warriors. Still Pitchlynn proposed a treaty of peace and after much equivocation and, delay the Osages consented to meet Pitchlynn and his little band in council; but nothing definite was done on the first day, though Pitchlynn told them that he and his party, the first Choctaws that had ever proposed peace to the Osages, had traveled over two thousand miles through the request of the United States government, to propose a treaty of perpetual peace and friendship to the Osages. To which an Osage chief made a haughty and defiant reply. The next clay in council assembled, Pitchlynn also assumed an air more of haughty defiance than that of a suppliant for peace, and in his speech, in reply to the Osage Chief’s speech made the day before, boldly said: “After what the Osage warrior said to us in his talk yesterday, we find it difficult to restrain our old animosity. You tell us that by your laws it is your duty to strike down all who are not Osage Indians. The Choctaws have no such laws. But we have a law, which tells us that we must always strike down an Osage warrior whenever we meet him. I know not what warpaths you may have follower west of the Great river, but I know very well that the smoke of our council fires you have never seen, as we live on the other side of the Great River. Our soil has never been tracked by an Osage, only, when he was a prisoner. I will not, as you have done, boast of the many warpaths we have followed. I am in earnest and speak the truth, when I now tell you that our last war-path, since you will have it so, has brought us to the Osage country, and to this village. The Choctaw warriors now at home would be rejoiced to get a few hundred of your scalps, for it is thus that they get their reputation as warriors. I tell you this to remind you that we also have some ancient laws as well as the Osages, and that the Choctaws know too how: to fight. Stand by the laws of your fathers, and refuse the offer of peace that we have now extended to you, and bear the consequences that will follow.

“We are now a little band in your midst, but we do not fear to speak openly to you and tell you the truth. We expect to move soon from our ancient country east of the Great River to the sources of the Arkansas and Red rivers, which will bring” us within two hundred miles of your country; and then you shall hear the defiant war-whoops of the Choctaws in good earnest and the crack of their death-dealing rifles from one end of your country to the other; nor will they cease to be heard until the last Osage warrior has fallen; your wives and children carried into captivity, and the name of the Osages blotted out. You may regard this as vain boasting, but our numbers so much exceed that of your own that I am justified, as you well know, in my assertion. You say you will not accept the white paper of the Great Father at Washington; therefore, we now tell you that we take back all we said yesterday about a treaty of peace. If we are to have peace between the Choctaws and Osages, the proposition must now come from the Osages. I have told you all I have to say, and shall speak no more.”

This bold speech of Pitchlynn’s had the desired effect, causing a great change to come suddenly over the spirit of the Osages dreams; therefore, on the next day the council was again convened and the Osages, without further solicitations, negotiated for peace, which was soon declared, and followed by a universal shaking of hands and great demonstrations of friendship, intermixed with un-assumed joy in the happy result. A grand feast was at once prepared, at which everything presented a joyous appearance, while peace-speeches furnished the greater part of the entertainment; the honor of delivering the closing speech was awarded to Pitchlynn, in which, with his usual eloquence, he portrayed before the eyes of the attentive Osages the benefit that would, accrue to them as a Nation to lay aside their old manner of living and begin a new kind of life that of adopting the customs of civilization. He spoke of his own people, the Choctaws, who had conformed to the customs of civilization, by encouraging white missionaries to come among them and teach them; by establishing schools for the education of their children, and by turning the attention of the men to the cultivation of the soil; and had given up war as a source of amusement, and hunting as their sole dependence for food, and how much benefit they had already derived in so doing, and he would advise the Osages, as well as all Indians, to do the same; as it was the only means of preserving themselves from the grasping habits and power of the white men. If they would make an effort to elevate themselves in the scale of civilization, the American government would treat them with greater respect, and they thus would preserve their nativity.

At the close of the peace ceremonies and festivities a party of Osage warriors, with the Osage speaker of the Council, were appointed to escort, as token of peace and friendship between the Osages and Choctaws, Pitchlynn and his little company to the borders of the Osage territories, a distance of one hundred and fifty miles. There the Osage escort bade their old enemies, but now newly-made friends, a formal adieu, and returned to their villages, while Pitchlynn and his five companions, after an absence of nearly six months, turned their faces homeward with light hearts, pursuing a southern direction down the Canadian river, and continuing along the Red river valley, and finally reached home in safety.

Peter P. Pitchlynn, while upon this adventurous journey, picked up a little Indian boy belonging to no particular tribe, whom he adopted and carried home with him, had him educated at the Choctaw academy in Kentucky; and that homeless boy of the western prairies became one of the most eloquent and faithful preachers that ever preached the Glad tidings of great joy among the Choctaw people.

Peter P. Pitchlynn first formed an acquaintance with the great American statesman, Henry Clay, in 1840, when traveling on a steamboat. While on board, he one day heard two apparently old farmers discussing the subject of agriculture, to whose conversation he was attracted, and soon became a silent but deeply interested listener for more than an hour; then going to his state-room he told his traveling companion what a treat he had enjoyed in the discussion between “two old farmers” upon the subject of farming, and added: “If that old farmer with an ugly face had only been educated for the law, he would have been one of the greatest men in this country.” That “old farmer with an ugly face” was Henry Clay, who was delighted at the compliment paid to him by the appreciative Choctaw.

The noble Peter P. Pitchlynn was in Washington City at the time of the commencement of the civil war in 1861, attending to the national affairs of his people, but at once hastened home, hoping that they would escape the evils of the expected strife, and returned to his home to pursue the quiet life of a farmer among his own people. But the Choctaws, as well as the Chickasaws, Cherokees, Creeks and Seminoles, from their position between the contending parties, were not permitted to occupy neutral grounds, but were forced into the fratricidal strife, some on the one side and some the other, but to the inconceivable injury of all.

Of Peter P. Pitchlynn it can be said, he was teacher, philosopher and friend among the Choctaws, cherishing with great pride the history and romantic traditions of his people. As a private citizen, he was a good man; as an official and public servant, he was a pure man. As a high official in his country, he too was a pious man; nor thought the religion of Jesus Christ derogatory to the position of a public official, but taught to all the lesson of personal grace as produced in the heart, and won from those who knew him their esteem, reverence and praise. His daily walk, both in public and private capacity, was as bright as the sunshine and as beautiful too. It truly seemed as if nothing could disturb his serenity, so evenly was it spread over his life, and so much did it seem to be a part of it. He was one of those Christian men who carried the charm of an attraction with them everywhere. He possessed such sweetness of spirit, such gentleness of manner, such manly frankness, such thorough self-respect on one hand, and on the other, such perfect regard for the judgment of others, that one could not help loving him, however conscience might compel conclusions on matters of mutual consequence unlike those he had reached. Often indeed, one was even more drawn to him when in opposition; because he was so true and just that his respect carried with it all the refreshment of variety with none of the friction of hostility. His character possessed a completeness and grandeur rarely found, and the virtues which distinguished him were many, both excellent and winning. His unswerving fidelity in religion, so remarkable in the Choctaws, and his eminent purity of life, ever shone out brightly in all the circumstances in which he was placed, whether in the private or public walks of life. And with all he was a spirited citizen of his country, who lived and labored, not for selfish gain and self-emolument, but for the good of his people, and always felt a lively interest and performed an active part in any and all things looking to the welfare of his country. The loss of such a man may well be mourned, and his example sacredly treasured and followed. In the light of a spiritual sun he passed from the scenes of earth, but his influence lives, and illustrates the new creative power that is possible to all.