Unfortunately, acid rain in recent decades have made most petroglyphs barely visible.

In mid-July, a member of the Unicoi Turnpike Preservation Association, telephoned me after reading an article that I had written in the Examiner. That particular column was about archaeological sites in western North Carolina. He was also a member of the Towns County, GA Historical Society. The Union County-Towns County line runs across the peak of Brasstown Bald Mountain, which contains Georgia’s highest elevation. Brasstown Bald is immediately to the east of Track Rock Gap.

The outdoor enthusiast was primarily interested in what I knew about the use of the Unicoi Turnpike during the Trail of Tears Period (1836-1838.) The Unicoi Turnpike was a 19th century road that improved an ancient Native American trade path between the headwaters of the Savannah River in northeast Georgia and the confluence of the Tennessee and Little Tennessee Rivers near Loudon, TN. He wanted to know if I thought it was used to move Cherokees to prison stockades in the summer of 1838.

I wanted to talk about the evidence that I had found which indicated that Spanish explorer, Juan Pardo, had used the Unicoi Trail in 1567. I thought perhaps Spanish Jews had followed the trail to settle the Georgia and North Carolina Mountains. He was only mildly interested that subject, and was primarily focused on preserving the sections of the Unicoi Turnpike that might have been traveled by Cherokees.

The Unicoi Trail was outside the Cherokee Nation in 1838, when thousands of Cherokees were being deported. I told the local historian that I had read some accounts where Cherokees living outside the boundaries of the “Nation” had escaped federal troops by traveling on the Unicoi Trail to the Tennessee section of the Smoky Mountains, where no federal troops were patrolling.

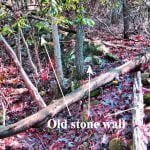

As an afterthought, I asked him about the stone walls I had seen at Track Rock Gap. He told me that there were stone walls and stone piles all over the place on the east side of Track Rock Gap. He added that through the years, he had seen several other complexes of stone walls or piles of stones in other parts of the mountains, particularly in Towns County. He said that there were even some stone piles on the flanks of Brasstown Bald, near the Unicoi Gap.

There was another surprise. Archaeologists, working for the U. S. Forest Service , had studied the Track Rock petroglyphs about a decade before. The next year, a local citizens group had paid the same firm to study the stone structures on the east side of Track Rock Gap. Several people involved with the preservation of the Unicoi Turnpike had contributed to the second archaeological study. The gentleman said that he would find me a copy of it.

A few days later, I received an email from Cary Waldrup, a retired electrical engineer who lived near Track Rock Gap. Attached to the email was a digital copy of a report on the Track Rock Archaeological Zone prepared in 2001 by South African archaeologist, Johannes Loubser. I looked at the site plan of the half square mile tract. It looked like a terrace complex from Central America or the Andes. This was not what I was expecting to see.

- Download a PDF of the Loubser and Frink article: Appraisal of a Piled Stone Feature Complex

After racing through the first few paragraphs of the report, I jumped to the pages where there were lab analyses of soil obtained from the two test pits that Loubser dug. I was astonished by the radiocarbon dates on the charcoal found in the fill soil of the single terrace examined. The oldest date was 1018 AD. The terrace had been constructed at least a thousand years ago. Loubser stated that some of the pottery shards found mixed with the fill soil could be old as 750 AD.

The stone structure complex at Track Rock Gap was not a Sephardic mining village from the 1600’s. Well, at least it was not originally built by Spanish Jews in the 1600’s. I shook my head in astonishment. What was this place and who built it?