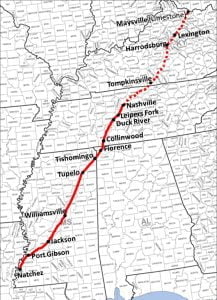

In 1792, in a council held at Chickasaw Bluffs, where Memphis, Tennessee, is now located, a treaty was made with the Chickasaws, in which they granted the United States the right of way through their territory for a public road to be opened from Nashville, Tennessee, to Natchez, Mississippi. This road was long known, and no doubt, remembered by many at the present time by the name “Natchez Trace.” It crossed the Tennessee River at a point then known as “Colberts Ferry,” and passed through the present counties of Tishomingo, Ittiwamba, Lee, Pantotoc, Chickasaw, Choctaw, thence on to Natchez, and soon became the great and only thoroughfare for emigrants passing from the older states to Mississippi, Louisiana and South Arkansas. Soon after its opening, it was crowded by fortune seekers and adventurers of all descriptions and characters, some as bad as it was possible for them to be, and none as good as they might be.

One of the most noted desperadoes in those early days of Mississippi’s history was a man named Mason, who, with his gang of thieves and cut-throats, established himself at a point on the Ohio river then called “The Cave in the Rock,” and about one hundred miles above its junction with the Mississippi river. There, under the disguise of keeping a store for the accommodation of emigrants, keel and flat boatmen passing up and down the river, he enticed them into his power, murdered and robbed them; then sent their boats and contents to New Orleans, through the hands of his accomplices to be sold. He, at length, left “The Cave in the Rock,” and sought a new location on the Natchez Trace, where he established himself, and soon attained to such a power, that he and his well-organized band of outlaws became a terror to all from the banks of the Mississippi river to the hills of Alabama and Tennessee. Over this wide extended territory he was monarch of all he surveyed for several years; and though many efforts were made by the law abiding citizens to kill or capture him and break up this nest of land pirates, yet he always managed to outwit his pursuers and elude their grasp. Ultimately a strong party organized themselves at Natchez and went in pursuit of the daring robber, resolving to kill or capture him at all hazards but was out generated by the sagacious and ever watchful desperadoes. The company having arrived on the banks of the Pearl River, soon learned that the object of their search was in the vicinity, but before making an attack upon him, they concluded to dine, feed and rest their horses. During this, two of the company, allured by the anticipated delight of a swim, plunged into the cool and clear waters of the river and swam to the opposite bank, but to give themselves into the hands of the vigilant Mason, who, cognizant of all the proceedings and designs, had closely watched their maneuvers, by which he soon found himself enabled to accomplish by stratagem, what he could not perhaps, by force.

Having secured the two thoughtless and inconsiderate fathers, Mason at once assumed a bold and defiant attitude, and called out to his would-be capturers on the opposite bank and informed them that all further demonstration of hostilities on their part would be followed by the instant death of their two captive friends; and also stated if they wished to save the lives of their two companions to stack their guns and ammunition at once on the banks of the river at a designated place and he would send for them; if they manifested the least disposition to interfere with his messenger his two prisoners would be instantly slain; but if they punctually and obediently complied with his demand he would return their two friends, unharmed, to them, at the same time pledging his word of honor to the performance of the same. The demands of Mason were duly obeyed and several of his party swam across the river and took possession of the guns, while the two captives were placed in full view with rifles pointing in unpleasant proximity and in direct line to their heads. Then Mason released his prisoners and bade them return in the way they came; to which they gladly and with out hesitation complied. He then sternly ordered the crest fallen company to mount their horses and return to Natchez, adding that it would not be healthy for them to indulge in a hunt again for him, as he would not let them off so gently if they should again fall into his hands.

Treachery finally effected what all other means failed to accomplish. Shortly after, a man of high standing and his two sons were robbed by a party of Mason’s band, as they were passing along the Natchez Trace, though they received no bodily injury. After their return home, Governor Claiborne, of the Mississippi Territory, offered a large reward for Mason, dead or alive, a copy of which soon found its way to the notorious bandit, over which, it is said, he manifested much merriment. But the reward proved too great a temptation for two of his band, and they treacherously slew Mason and carried his head in secret triumph to Gov. Claiborne. It was at once recognized by many of the citizens. But the joy of the two traitors in anticipation of the reward was of short duration, since among the many spectators were the two sons, who, with their father, had been robbed shortly before, and who at once recognized the two scoundrels as being of the party who had robbed them. At once they were arrested, tried, convicted, and paid the penalty of their crimes upon the gallows. And thus was broken up one among the most notorious gangs of robbers that infested the Natchez Trace.

However, another daring gang sprang up a few years after the death of Mason, under the leadership of one John A. Murrell who also sought upon the Natchez Trace their victims to murder and plunder during the years 1830 and 1840. And numerous were the bloody deeds and daring robberies committed by those bold free-booters upon the lonely traveler who had the nerve to venture through that long stretch of wilderness and solitude alone: and the thefts of horses and Negroes from the planters, especially the Negroes, whom they enticed away under the promise of taking them north to a free state; then, after selling and stealing them a few times under the pretense to the deluded Negroes of getting money to defray their expenses to a free state, they would kill them and sink their bodies in a river or lake. Murrell was finally captured, tried and condemned to life imprisonment in the penitentiary at Nashville, Tennessee. After a few years of confinement he professed religion (it was said), and his health failing, he was eventually pardoned, then became a preacher of the Gospel, and shortly afterwards died.

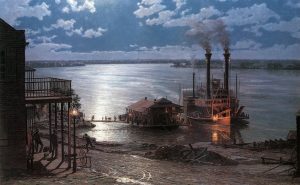

General Andrew Jackson led his victorious army along this road (the Natchez Trace) on his return from New Orleans, in 1815. Before steamboats began to plough the waters of the Mississippi river, all kinds of produce were transported to New Orleans in keel and flat boats from the upper countries. When arriving there both boat and cargo-were sold, and the owners with their employers returned home, some on horseback and more on foot, by the way of the “Old Natchez Trace.” Bands of those rough and fearless boatmen flocked along on the old trace to their distant, homes in North Mississippi, Tennessee and Southern Kentucky. The intervening wilderness of forests were illuminated with the camp-fires, and the midnight silence of the: then vast solitudes broken by their bacchanalian revelries.. All characters blended together in those straggling bands of wild and reckless humanity; the jolly boatmen whose lives were spent on the bosom of the majestic “Misha Sipokni ” and in the romantic and fascinating jollifications of their camp; men of education and refinement; adventurous youth, who never before was out of sight of the smoke of his, native village or humble home; the sturdy farmer; the shrewed trader; the calculating merchant; the wily gambler, and the daring robber, were, to a greater or less extent, represented.

But the “Old Trace” has long since been effaced by the ploughshare and buried in the field of forgetfulness amid the corn and cotton plantations, together with the throbbing-hearts, then buoyant with hope and elated with joy, distracted with fear or burdened with care that followed its, windings and dubious ways through the Chickasaw and Choctaw Nations nearly a century ago, and sang or wept laughed or sighed along that old forest road, and have become as silent and as little remembered as the multitudes that once thronged the busy streets of ancient Tyre, while oblivion has woven her raven web and thrown it upon the “Old Natchez Trace” to be remembered “never more.”

“Natchez-Under-The-Hill” was, at that early day, the: “sine qua non” as the point of rendezvous for the rough and (care-for-nothing men who navigated the keel and flat-boats on the Mississippi river ere they were superseded by the steamboat. At that early day the city of Natchez was an excellent market for the products of the “upper country,” consequently hundreds of heavily and richly-laden boats often congregated there, to the great dread of the law-abiding and peaceful inhabitants residing in the upper part of the city, then known as “The Bluff;” for the wild and law less boatmen knowing no restraint, and without the fear of God or man, indulged their caprices in every kind of rowdy ism known to man; and often breaking through the acknowledged limits of their own district, “Natchez-Under-The-Hill,” they carried the city “On The Bluff ” by storm, not unlike a genuine cyclone of the present day, riding rough shod over the law and every physical obstruction that impeded their headlong course. Then, having had their “fun,” during which they had drank and destroyed all the whisky they could lay their hands upon, they returned to the plateau “under the hill” with songs and hideous yells, where, perhaps, they would meet with another gang of their own faith and order, and a fight would ensue, in which the Herculean strength there and then displayed has no parallel, except in Homer s description of the fabulous wars between the gods. Thus did those specimens of American freemen, spend their leisure hours in drinking whiskey, yelling, fiddling, dancing and fist-fighting, the latter seeming a direful necessity, an unconquerable appetite, which, like hunger, must be appeased at all costs; and even when quietness had assumed her sway in camp, often it would be unexpectedly and unceremoniously disturbed by some aspirant to fame loudly crowing forth his defiance like a game cock, which was sure to be answered by another in a different part of the camp, and the natural result is easily guessed, since he who boasted according to the approved style of the game cock, virtually proclaimed he had never been whipped, and, there fore occupied a dangerous eminence, as some equally ambitious aspirant was sure to be in hearing of the midnight challenge, and equally ready to dispute his claim to such distinction.

Still those apparently lawless men had a code of honor among themselves to which they strictly adhered and implicitly obeyed. “Fair play” was a jewel among them; and in all disputes and difficulties they invariably took up the cause of the weaker, and always espoused that of the aged, right or wrong.

In 1794 the United States Government secured the aid of several companies of Chickasaw warriors to co-operate with its troops against some of the northwestern tribes of Indians with whom it had become involved in war; and though the cause is not now known, yet it may with safety be easily guessed, as, like the English and French before it, so it also arrayed one tribe against another in its own wars with that credulous people until partially destroyed, then gobbled up all (allies and enemies) at a swoop. The following is a war commission given by George Washington, then President of the United States, to a Chickasaw chief called Mucklesha Mingo (corrupted from Mokulichih Miko to outdo or excel chief). The chief who excels:

George Washington, President of the United States of America. To all who shall see these presents greeting:

“Whereas, I am authorized by law to employ such a number of Indians and for such compensation as I shall think proper, within certain limitations, to act against the hostile tribes northwest of the Ohio.

“And, whereas, it is expedient that in case of such an event certain chiefs should be previously designated; and having full confidence in the well tried friendship of Muckle-shamingo a chief of the Chickasaw Nation, I do hereby appoint him to rank and to receive pay as Captain of Militia while he shall actually be in the service of the United States, and co-operating with the troops thereunto belonging. And I do hereby direct that on such occasions he be respected accordingly.

Given under my hand at Philadelphia, this the 20th of July, in the year of our Lord 1794, and in the 19th year of the Independence of the United States.

“G. Washington.

“By command of the President, J. Knox.”