Information as to the region occupied by the Cheyenne in early days is limited and for the most part traditional. Some ethnologists declare that Indian tradition has no historical value, but other students of Indians decline to assent to this dictum. If it is to be accepted we can know little of the Cheyenne until they are found as nomads following the buffalo over the plains. There is, however, a mass of traditional data which points back to conditions at a much earlier date quite different from these. In primitive times they occupied permanent earth lodges and raised crops of corn, beans, and squashes, on which they largely depended for subsistence.

La Salle says that the Chaa – (?) Sharha – in 1680 told him that they lived about the head of the Great river, and Carver, in 1766, mentions the Schians as found in the great camp of Indians which he visited on the Minnesota river. The Schianese he says live further to the west. Nearly one hundred years later Riggs and Williamson repeat Sioux traditions which declared that in earlier times the Cheyenne had lived on the Minnesota river, but had moved westward.

Two points of permanent occupancy by the Cheyenne seem to be generally accepted; one an earth-lodge village located on the Sheyenne river, a tributary of the Red river from the west – near the present Lisbon, in North Dakota – and the other two neighboring village sites on the Missouri mentioned by Lewis and Clark in 1804, pointed out to them by a Ree chief as having been formerly occupied by the Cheyenne.

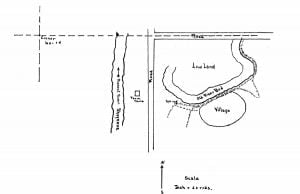

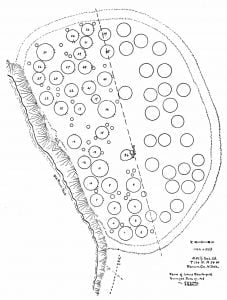

The village site near Lisbon (fig. 33) was examined and mapped some years ago by Dr. Libby and Dr. Stout, and a plan (fig. 34) of it is now in the archives of the Historical Society of North Dakota. The two villages mentioned by Lewis and Clark have been roughly located by students of the journals of these explorers.

In the report of the Smithsonian Institution for 1871, Dr. Comfort describes his investigations into certain mounds which he found near Kettle lakes, west of lake Traverse, which he speaks of as made by the Cheyenne.

Disregarding the earliest and very vague traditions of the Cheyenne with regard to their most ancient wanderings and treating Tsis tsis tSs and Suhtai as a single group, we find that there still remain in the tribe accounts of a time when they lived on the borders of large lakes in a region which was wholly timbered. This country was presumably in the present state of Minnesota, or to the northeast of that. Later they speak of a blue water, or river, flowing through a “blue earth” country, near which they lived for a long time. This was perhaps the Minnesota river.

Dr. T. S. Williamson 1 records among the “common and most reliable traditions” of the Sioux, one which states that when the ancestors of the Sioux first came to the Falls of St. Anthony the Iowa occupied the country about the mouth of the Minnesota river, and the Cheyenne dwelt higher up on the same river. He states also that the Cheyenne formerly planted on the Minnesota between the Blue Earth and Lac qui Parle.

Writing about 1850, Dr. Riggs 2 says that “two hundred years ago or thereabouts” the Cheyenne had a village near the Yellow Medicine river in Minnesota, where are yet visible old earth works; that from there they retired to a point between Big Stone lake and lake Traverse, where they had a village, and then moved to the south bend of the Sheyenne river, a tributary of the Red river of the north. This last village is the one near Lisbon, N. D. From the site on the Sheyenne river, the Cheyenne are assumed to have moved toward the Missouri river, and when they reached it are said by Riggs to have had a village on the east side and afterwards to have crossed the river and to have lived with or near the Mandan.

Dr. Comfort in his account of Indian remains 3 – near Fort Wadsworth, west of Sisseton, S. D. – speaks of the occupancy of the region by the Cheyenne as well known, and states that “the Cheyenne about one hundred years ago were dispossessed of the soil by the Dakotas.” The village referred to by Dr. Comfort is not the Lake Traverse village said by Riggs to have been occupied next after that on the Yellow Medicine, but Comfort speaks – p. 398 – of mounds and earth works on the shores of lake Traverse which might be the traditional site referred to by Riggs.

Dr. T. S. Williamson 4 says of the return of the Sioux to the Minnesota river, perhaps many years after their first visit:

The Cheyennes were then in the upper part of the valley; and near the Yellow Medicine a fortification is still plainly visible, which it is said was made by them near a good spring of water, and in 1853, when the first plowing for the Sioux was done in that region, large quantities of muscle shells were turned up near the remains of this fortification, indicating that the ground had been cultivated. The Sioux who expelled the lowas, a kindred race, made a league with the Cheyennes, who, though of a different origin, have ever since been counted a part of the Dakota nation.

Of the settlement on the Yellow Medicine, Dr. Riggs 5 says:

The excavation extends around three sides of a somewhat irregular square, the fourth being protected by the slope of the hill, which is now covered with timber. After the filling up, of years, or perhaps centuries, the ditch is still about three feet deep. We found the east side, in the middle of the ditch, to measure thirty-eight paces, the south side sixty-two, and the west side fifty. The north side is considerably longer than the south. The area enclosed is not far from half an acre. On each of the three excavated sides there was left a gateway of about two paces.

An early reference to the village on the Sheyenne river appeared in 1863, from the pen of the same author. 6 He says:

The village stood on the southeast side – of the river – on a high piece of land abutting on a swale which contains springs of living water. More than fifty years have passed since its abandonment by the Cheyennes, but the fortifications are all easily traced. The ditch that encircled the village proper is now, in places, three feet deep. It terminates at either end at the bluff blank and is the shape of a half-moon, a little gibbous. It includes between two and three acres of ground. This place was thickly settled with houses. Some sixty or seventy of these houses stood inside the fortifications. Then outside the city were suburban residences, but they were not sunk into the ground nearly so much as those on the inside.

In 1850 the stream on which this village site stands was still called by the Sioux Sha hī’ ē na wojupi. Where the Cheyenne plant. Later Dr. Riggs writes,

Dakota tradition says that it was for a great many years successfully defended by the Cheyennes against the hostile Sioux, that many bloody battles were fought there, the Sioux often being driven back with great slaughter.

In a periodical entitled The Monthly South Dakotan, vol. 11, no. 4, August 1899, p. 56, is a description of the village by Hon. A. L. Van Osdel of the Sibley Expedition of 1863 – the one that Dr. Riggs accompanied. The account possesses a certain interest, but apparently the writer has endeavored to make it vivid by suggesting that the site had been recently abandoned. In fact, in one place he says

Several old dirt lodges were still standing, delapidated and in the lost (sic) stages of decay. These old structures were built in a circular form and were from fifteen to twenty feet in diameter.

Interesting, however, is the fact that this writer has hit upon the truth as to the enemies with whom the Cheyenne fought, and declares that the battles of those who had formerly occupied this place were with the Assiniboine Sioux. This he repeats more than once, and in this he is right, for the fighting of the Cheyenne was with the Assiniboine Sioux, and not with any other Sioux.

The village on the Yellow Medicine was of small extent, and could have been occupied by only a small number of people. One half an acre of land – Dr. Riggs’ estimate – would have held but a few lodges. The village on the Sheyenne river was much larger, yet its 60 or 70 lodges, would have hardly housed more than 500 or 600 inhabitants.

Dr. Riggs and Dr. Williamson seem to assume that the different village sites in Minnesota and North Dakota were occupied successively, but I believe that this was not the case. It seems more probable that several of the different villages were occupied at the same time and were merely different, scattered, if permanent, camps or villages of different bands of Cheyenne, just as, a few generations ago, different sections of the Pawnee tribe occupied their permanent villages at distances one from another in portions of Kansas and Nebraska.

Although, so far as known, the Cheyenne were never a large tribe, yet as long ago as 1820 Morse 7 gave their number as about thirty-five hundred; and this did not include the Suhtai, then not identified with the Cheyenne. In none of the known settlements of the Cheyenne east of the Missouri river could such a number of people have been accommodated.

I have no doubt that for a long time a number of contemporary Cheyenne villages were scattered along the Minnesota river and to the west of that, and that some of these, after they had been occupied for a generation or two, were abandoned and new locations sought elsewhere. At all events the trend of tribal movement was westward, and this at last brought the Cheyenne to the Missouri river.

In the movement of a group of Indians, a camp or village followed its own ideas as to where it wished to go and did not usually consider the movements of other camps. It moved independently. There was no contemporaneous tribal migration. The different camps did not unite in a forward movement. The trend of the tribal movement being westward, a group moved on, established itself at a point and remained there for a time – perhaps for many years, perhaps for a generation or two. Later, some village behind it moved forward, passed the first village and stopped somewhere beyond. The gradual westward progress consisted of a succession of such movements, the tail of the long procession often becoming the head, and the different camps or villages moving on successively and passing each other. Since for all the people the important question was that of subsistence, it is evident that when a place was found especially favorable for the procuring of food, the camp would remain there longer than it would in a place where the subsistence was less easily had – would be likely to remain in fact until food became difficult to obtain.

The tribal movement westward in fact may almost be compared to the familiar actions of a flock of feeding black birds – or old time wild pigeons – walking over a field in a broad front. The birds in the rear ranks constantly rise on the wing and fly over their fellows to alight just in front of them, where the ground has not been passed over and the food has not been consumed, while the whole front walks forward. In the same way – though slowly – the rearmost camps of the migrating Cheyenne were constantly moving onward and passing those in advance of them in the hope of finding new regions where food might easily be had.

Most early writers who mention the Cheyenne speak of them as having been driven southwest by the Sioux, but, I believe that these statements are due to misunderstanding. Although Lewis and Clark, 1804, Alexander Henry the Younger, 1806, the Rev. Mr. Riggs, 1850, or thereabouts, and W. P. Clark, 1884, all repeat the same story, I am convinced that it is misleading. Long continued inquiry among the Cheyenne reveals no account of any wars with those tribes which we commonly called Sioux, that is the southern branches of the Dakota group. Carver speaks of the Cheyenne as camped in 1766 with the Nadouwessi of the Plains. The western Sioux today declare that they have always been friends of the Cheyenne and Rev. T. S. Williamson says – as stated – that the Cheyenne, have ever since (their first meeting) been acknowledged a part of the Dakota nation. John Hay 8 in his notes on Capt. Mackay’s Journal says that the Chayennes or Shayen – who formerly lived on the tributary of the Red river of that name – were so harassed by the Assiniboine and Sioux that they had to leave their village and go to the Missouri river.

The Hohē – the Assiniboine – however, are constantly spoken of by the Cheyenne as enemies, and inquiry among the Yankton, Hunkpatina, and Teton Sioux now settled on the Missouri river in North Dakota and South Dakota seems to show a general agreement that the Assiniboine were their enemies also, while the Cheyenne were their friends. The Assiniboine used to make war journeys against Sioux and Cheyenne alike. I believe that the Cheyenne tradition of their being driven south by the Hohē refers to early attacks on them by the Assiniboine, perhaps in company with the Cree at first and later with the Ojibwa. That there may have been occasional individual quarrels between Cheyenne and Sioux and between Cheyenne and Mandan is possible and even likely, but, I believe nothing in the nature of a general war.

Dr. A. McG. Beede, of Fort Yates, N. D., wrote me some months ago concerning certain Sioux traditions as to Cheyenne settlements on the Missouri river, and in May last (1918) I went to Fort Yates to make further inquiry into the matter. The Teton Sioux, now allotted and scattered over the Standing Rock Indian reservation, declare that on the west bank of the Missouri river, not far from Fort Yates, there were formerly two Cheyenne villages, and with Dr. Beede I visited the two sites.

The most northerly one is situated on a bluff above the Missouri river on the south side of Porcupine creek, less than five miles north of Ft. Yates. The village has been partly destroyed by the Missouri river, which has undermined the bank and carried away some of the house rings reported to have been well preserved, but a number remain. Of these a few are still seen as the raised borders of considerable earth lodges, the rings about the central hollow being from twelve to fifteen inches above the surrounding soil, and the hollows noticeably deep. In most cases, however, the situation of the house is indicated merely by a slight hollow and especially by the peculiar character of the grass growing on the house site. The eye recognizes the different vegetation, and as soon as the foot is set on the soil within a house site, the difference is felt between that and the ground immediately without the site. The houses nearest both Porcupine creek and the Missouri river stand on the bank immediately above the water, and it is possible that some of those on the Porcupine have been undermined and carried away by that stream when in flood.

This settlement must have been large. It stands on a flat, now bisected by a railroad embankment, slightly sloping toward the river, and the houses stood close together. Many of them were large, one at least being 60 feet in diameter. Besides the large houses there were a great number of smaller ones, probably occupied by small families, by old people living alone, or used as menstrual lodges, or perhaps even for dogs. Including the area east and west of the embankment we counted more than 70 large house sites, taking no account of the small ones. The houses extended several hundred yards back from the river, that is, toward the west, and 150 or 200 yards north and south. It is probable that once they were much more numerous, and they may even have extended a long way down the river, for about two miles below are evidences of another village, said by the Sioux also to have been a Cheyenne village. On the site of this last old village many years ago, a group of Standing Rock Sioux built a number of log houses, the foundations of which have largely obliterated the evidences of the earlier supposed Cheyenne village. This loghouse village was known locally as “Slob town.”

On the gently rising land to the west of the Porcupine village the Cheyenne are said to have planted their corn, as also on the flats on the north side of the Porcupine river. The village site now stands on the farm of Yellow Lodge, a Yankton Sioux, who stated that he had always been told by the old people that this was a Cheyenne village and that in plowing he had often turned up pottery from the ground. Most of this pottery was broken, but he had found some pots that were perfect. He had turned up also glass beads, which he described as like the charms or beads which we know the Cheyennes used to manufacture – in later times perhaps from pounded glass like those said to have been made by the Mandan.

At the time it was impossible to procure any pottery which had been turned up by Yellow Lodge.

Some days later, in company with Dr. Beede, I proceeded to the farm school, less than fifteen miles south of Fort Yates, to examine remains there, also said by the Sioux to be of Cheyenne origin. The farm school is just over the boundary line between North Dakota and South Dakota, perhaps three miles south of the mouth of Blackfoot creek and a mile below what I suppose to be Eagle Feather creek, and seems to have been established in the very center of this old Indian village. It is east and a little north of the Cheyenne Hills. 9 Just above Blackfoot creek and on the state boundary line is an old village site with three mounds and many house sites said by the Sioux to be Mandan.

To the south and southeast of the school are a dozen or twenty house rings, and to the north, close along the river, are other house rings. Within the boundaries of the farm school are three low mounds. One of these has been excavated to make a root cellar, and by one of the men who had helped dig the cellar I was told that a considerable amount of pottery fragments had been thrown out. On another mound stands the Roman Catholic chapel; and a low mound almost within the school enclosure is partly occupied by one of the office buildings of the school. To the south of the school buildings and on or among the old house rings, are a number of places where modern Indian houses have stood, and small tracts which have been cultivated as gardens within recent years, and are still more or less overgrown with weeds.

The superintendent of the farm school had never heard of a Cheyenne village here, nor of any evidences of Indian occupancy, nor had he seen any pottery fragments. He seemed interested in what we said and walked with us out to a small piece – half an acre – of ground, just south of the school building, the sod of which had been broken only the day before. Here, walking over the newly turned sod I presently found a piece of pottery, which proved to be a part of the rim of a vessel. The fragment is less than two inches wide and two deep. Below the rim extending down perhaps an inch and a half from the unmarked lip of the pot are four lines of ornamentation, parallel to the lip and to each other.

Later several small and unornamented fragments of pottery, two or three flint chips and a few fragments of Unio shells, were found. Alexander Sage, a Mandan Indian about forty years old, employed at the school when shown the ornamented piece of pottery said that it was not Arikara nor Mandan and inferred that it was Cheyenne. Nothing more was seen here. This village was once of considerable size, and the way in which the houses at its border were placed suggests also that attacks by enemies were not anticipated. The cultivation of the soil, the erection of the school buildings, and the westward movement of the Missouri river, which continually undermines the high bank and causes it to drop into the river, have greatly reduced the area of the village.

A few days after this I showed the pieces of pottery picked up at the farm school village to a Northern Cheyenne woman about fifty years old. When she saw them she at once said “my grandmother used to make dishes like that” and described the method of manufacture and of ornamentation by strings of twisted grass – and later sinew – pressed into the soft clay.

I know of no undoubted Cheyenne pottery, yet as recently as fifty years ago, a few Cheyenne women still made clay vessels, though for the most part these had been supplanted by pots and kettles of metal. Among the collections of the American Museum of Natural History there is now a large unornamented earthen pot found eighteen or twenty years ago in the hills back of the Cheyenne village at the mouth of the Porcupine river. This may be a Cheyenne pot though I know of no evidence to connect it with any tribe. When discovered it was spoken of as an Arikara pot, perhaps for no better reason than that the Arikara were at that time the best known makers of pottery along the Missouri river. It is similar to pots known to be made by Mandan, Arikara and other village Indians.

A visit was made to Grand river to look for a Cheyenne village told of by the Sioux as located on that stream about seven miles below the post office of Bull Head, and near the camp where Sitting Bull was killed in 1890. The Sioux and Cheyenne name for Grand river is Ree river. 10

Elk River, born about 1814, often spoke of early days when the Cheyenne camped on the River of the Rocks, that is, the Cannonball River, and of the time when they lived on the Ree River.

There is still extant among the Cheyenne a song in which Ree River is mentioned. A young girl fond of a boy sings a song asking him if he intends to go to Ree river to marry. It is supposed that the boy was in the habit of leaving his home camp where the girl lived who made the song, to visit the village on Ree River, and she suspected that he was fond of some girl in that village.

There was no difficulty in finding the village site told of by the Sioux on the north side of Grand river, a mile and a half below Sitting Bull’s camp. Here were a few house rings within one of which was a hollow – a cache which had fallen in.

A few hundred yards further down the river, on a higher bench, we found many more house sites and in one or two of them the remains of caches. Some of the house sites were forty feet in diameter. They were often overgrown with low bushes. The village was a large one and the house sites ran back nearly half a mile from the river. Sometimes the houses stood close together, and the general plan of the village reminded me much of the old Pawnee village on the Loup river in Nebraska. On a sandy ridge near the river were found a number of large caches, apparently distant from any house sites. Some of these occurred in pairs – two deep holes rather close together. Their situation in the high dry sand seemed well adapted for protecting the stored corn from dampness. These caches were not far from the river bank and on the landward side were protected by the village. Though filled up by the debris of many years they were still quite deep, the surface of the debris being sometimes eighteen inches or two feet below the level of the soil. There must have been room for a great quantity of corn in each of these caches.

According to Sioux tradition some of the lodges here were so large that the Cheyenne took their horses into the lodges at night for protection. I found nothing to suggest the tribe which had occupied the village.

The account of his visit to the Cheyenne camp south of the Hidatsa in 1806 given by Mackenzie 11 – although he says nothing as to the direction in which he traveled on his way to that camp – mentions crossing the “Clearwater,” Heart and Cannonball rivers and suggests that the Cheyenne camp of 220 lodges that he visited was on what we know as Grand river. In 1811, the Astorians 12 under Mr. Hunt found on “Big River”‘ – i. e., Grand river – a large camp of Cheyenne.

The great Arikara village at the mouth of Grand river is well known. Whether the Cheyenne occupied this stream before the Ree or after them, or at the same time, is not known. The Cheyenne say – and no doubt this is true of some period – that the Ree were next below them on the Missouri river, and that the two tribes used to live close together, side by side. Some Ree took Cheyenne wives and some Cheyenne took Ree wives. There is much Ree blood in the Cheyenne tribe today.

On our return to Bull Head station we passed the remains of another village where “we saw a few house sites. The Sioux speak of this also as a Cheyenne village.

Heavy rains during my whole stay in this neighborhood had rendered the prairie a morass and it was difficult to get about. The whole country here, however, shows evidence of long occupancy by village Indians and is well worthy of further investigation.

Sioux tradition declares that the village on the Porcupine river was established about 1733 or a little earlier, perhaps 1730; they fix the date as about one hundred years before the stars fell, 1833. It was a large village and was occupied for fifty years or more and then the people abandoned it and moved over to a point on Grand river twenty miles above its mouth. The date of the removal is given as about the time of a great flood at this point, which, it is said, took place about 1784. The Cheyenne village remained on Grand river for a long time, probably as late as 1840, for Dr. Beede informs me that Red Hail, a Sioux (born 1833) often told him of visiting the village as a small boy, six or eight years old, and eating green corn there. At this time, however, according to this man’s memory, most of the people lived in skin lodges, not in permanent houses.

The people who settled on the Porcupine are said by the Sioux to have been the first Cheyenne to reach the Missouri river at that point, though long before this there were Cheyenne west of the Missouri river. The story is that they came from some village in the present Minnesota, described as being on the Minnesota river, near where Mankato now is, where they raised their crops. This account points to them as having lived on the Minnesota river near the mouth of Blue Earth near the old Sioux Crossing – Traverse des Sioux – perhaps in the locality referred to by Williamson and Riggs. At that old village, according to Sioux traditions, there are mounds built by the Cheyenne.

From this Minnesota home, these Cheyenne had journeyed westward, and had passed by the Cheyenne village on the Sheyenne river, which runs into Red river, and gone beyond that to a small flat on the head waters of Maple creek, west and a little south of the present town of Kulm, N. D. At that point, near Kulm, they had built a village and had lived there for a few years. Judge Beede tells me that he has seen there the remains of houses and some small mounds. This village was soon abandoned and they moved on westward, finally reaching and crossing the Missouri river.

Some time after the Cheyenne had established their village on Porcupine creek, still according to Sioux tradition, another group of Cheyenne made their appearance on the Missouri river, crossed into the village of their friends on Porcupine creek, remained there for a time and after no very long stay moved south to a point a short distance south of the present North and South Dakota boundary line, where they established a village a little up river and northeast of the Cheyenne hills. In other words, they established the farm school Cheyenne village, which the Sioux call the Cheyenne Plantings. This group of Cheyenne is said to be the one that long occupied the village on the Sheyenne river, near the present Lisbon, N. D. It is possible that these Sheyenne river Cheyenne may have built and for a time occupied the village two miles below the Porcupine on the site of which “Slobtown,” already referred to, was afterward built. They lived at the Cheyenne Plantings, i. e., the farm school site, for about twenty-five years and then, it is said, moved up Grand river to Dirt Lodge creek, where they built a village of earth houses. This is some distance west of the point on Grand river where the Cheyenne of the Porcupine river located.

The winter count of Blue Thunder, a Sioux historian still alive, records that it was 123 years ago, or in 1795, that the Cheyenne left the farm school village, and moved up to what is now called Dirt Lodge creek. The Sioux say that the Cheyenne village on the tributary of the Red river, near the present Lisbon, had been there for a long time, and the village was very old. It had often been attacked, but the Cheyenne had never been driven from it.

According to Sioux tradition there was a Cheyenne village on the east bank of the Missouri river, opposite the farm school village and there was also a well-known Cheyenne village on the Little Cheyenne river in South Dakota, near the former town of Forest City. This settlement on the Little Cheyenne, referred to by Riggs 13 is one of the many places still known to the Sioux by the name Sha hi’ en a wo ju’. It was occupied for a long time and finally the people are said to have abandoned it and to have moved south.

Old Sioux today talk about the village near Forest City opposite the present Cheyenne River Indian agency – i. e., on the Little Cheyenne river – and of fences, made of sticks set up in the ground criss-cross, and filled in with brush and weeds, which enclosed the corn fields at that place. Of late years, if a Sioux builds a fence where the carelessly set posts lean – are not upright – or are placed too close together the Sioux in derision say it is like the fence about Sha hī’ ēn a wo jū, referring to this old village on the Little Cheyenne.

Mr. Mooney’s statements in the Handbook 14 as to the farming practices of the Cheyenne seem to indicate that he is unaware, because they are not mentioned in that locality by Lewis and Clark, that they formerly lived on the Little Missouri – Antelope Pit river – and that they grew crops up to the middle of the nineteenth century. But the early Spanish Mss. map brought back by Lewis and Clark shows a camp of Chaquieno Indians near the head of the Little Missouri. 15

The testimony that they farmed up to 1850 is too general to be ignored. As just stated the Sioux still call a number of old Cheyenne village sites Cheyenne planting places and give various details as to the crops they grew, the way in which they protected them and the time when they moved on further west.

Old Cheyenne women, Wind Women, Ponca Woman, the wife of Brave Wolf, and many others, who were born in or near the Black Hills early in the last century, and who lived on the streams flowing out from them, have many times told me that they commonly planted corn patches, as their mothers before them had done, and had taught them to do.

Accounts of the capturing of eagles as practised from early times down to the first half of the nineteenth century describe as a ceremony connected with this eagle catching the preparation of a certain sort of ceremonial food, which consisted in part of balls of pulverized corn.

The growing of corn is always referred to as a commonplace incident and there is no doubt that it was usually grown. Knowing the conservatism of Indian women, we may feel certain that they would not easily have laid aside the agricultural practices that had come down to them through the generations, but that even after they had moved out on the plains, wherever the situation was favorable, and there was a prospect that they would return during the summer, the old women planted their crops and impressed on their daughters the duty of doing the same thing.

In a recent conversation with Hankering Wolf, who, in 1851, at the time of the Fort Laramie treaty, was a well-grown boy, he incidentally mentioned that, the year before that council was to be held, the Cheyenne put in their crops on a broad flat on the Platte river, just below the main canyon and above the first small canyon above Fort Laramie. It was from this point that they moved down on to the treaty ground at Horse creek.

The Cheyenne villages of which we are told by Sioux and Cheyenne tradition and which deserve further study are these:

- On Minnesota river near Mankato, Minn.

- On the Yellow Medicine, tributary of the Minnesota river – Williamson and Riggs.

- On Kettle lakes, N. D. west of Lake Traverse – Comfort.

- On Sheyenne river near Lisbon, N. D., called by the Sioux, Cheyenne Plantings. Already mapped.

- On the head of Maple creek near Kulm, N. D.

- On the east side of Missouri river opposite the farm school.

- On east side of the Missouri river on the Little Cheyenne river near – former – Forest City, N. D.

- On west side of Missouri river at junction of Porcupine creek and the Missouri.

- Two miles below Porcupine creek, possibly a part of Porcupine village, “Slobtown.”

- At Farm School near the Cheyenne hills.

- On Grand river, near Sitting Bull’s camp; and

- On Dirt Lodge creek, a tributary of Grand river. (perhaps)

Of these, numbers 4 to 11, inclusive, have been called by the Sioux – Cheyenne Plantings, Sha hī’ ēn a wo jū.

The Cheyenne today tell of villages on the Missouri, at the mouth of White river and of the Cheyenne river.

There seems reason to suppose that the villages just below Porcupine river (8 and 9) were those seen by Lewis and Clark October 15-16, 1804.

The most northerly identified point on the Missouri below these villages is Stone Idol creek, which Coues, Thwaite, and Quaife agree is Spring or Hermaphrodite creek. If we measure off on the Missouri River Commission’s map Lewis and Clark distances above the mouth of Hermaphrodite creek, we find that October 13 they camped a mile or more above the former Vanderbilt Post Office, on the north side of the river and nearly opposite – a little below – the farm school village. This is a little above the point where the river after flowing east turns south.

The following morning, October 14, the day on which the sentence of the court martial was executed, they left this camp, passed the farm school site – not mentioning Cheyenne ruins or the Cheyenne hills – which from the farm school site seem to answer very well the description given the next day – October 15 – of “curious hills,” like a slant-roofed house. They passed the small creek named, on the Missouri River Commission map Eagle Feather creek, and the larger creek above, the modern Blackfoot creek, which by Coues and Thwaite is considered the Eagle Feather creek of Lewis and Clark. Clark says they camped in a cove of the bank on the north, starboard, side and saw ruins on the south side, which however, were mostly washed into the river. This must have been near the mouth of the stream called Four Mile creek. But we cannot know where the course of the Missouri was at this time nor where Four Mile creek entered it.

The day after this, October 15, during the last three and a half miles of the day’s journey, they record, in courses and distances 16 passing a village of the Cheyenne Indians on the south side, below a creek on the same side. The following morning, just after setting out, they passed a circular work where the Cheyenne Indians formerly lived, and just above that saw a creek which they called Chien.

I am satisfied that these two sites are the villages at Porcupine creek, October 16, and at Slob town, October 15. There is now no running stream just north of Slobtown, though there is a water course which flows in spring. John C. Leach, an old resident, states that in 1 872 and in subsequent years this was a running stream which never went dry. Aged Sioux confirm this statement and say that up to twenty years ago the stream carried good water at all seasons and was used by the settlement of Slobtown. The Sioux say that when the old Cheyenne village here was occupied, there was abundance of good water which supplied the whole village and which did not freeze in winter. About sixty years ago a Ree Indian was killed near this creek, and since then the Sioux have called it Paláni wakpála, Ree creek. The name is not found on the maps.

Measurements of the distances between Lewis and Clark’s camps on the Missouri River Commission maps bring their camp of October 15 just below the mouth of the Porcupine, but I cannot locate it. If the Lewis and Clark route is figured back from the mouth of the Cannonball down to the mouth of the Hermaphrodite the distances agree with the Missouri River Commission maps to within two or three miles, as they do when the distances are figured upstream.

The bed of the Missouri river is, of course, constantly changing, and the course of the channel has no doubt greatly altered during the past century.

It seems probable that the last of the Cheyenne left the Missouri river and moved west toward the Black Hills more recently than is generally believed. Perrin du Lac found some of them at the mouth of White river not long before the advent of Lewis and Clark and says that they planted near their village corn and tobacco, which they returned to harvest at the beginning of the autumn. 17

This was precisely the method of the Pawnee. They planted and cultivated their crops in the spring and early summer and then set out on the summer buffalo hunt, from which in early autumn they returned to harvest their crops. It was perhaps mere accident that Lewis and Clark did not come upon an occupied Cheyenne village.

Near the end of the eighteenth century, if we may believe Cheyenne accounts and confirmatory traditions of the Sioux, several Cheyenne and Suhtai villages were still occupied along the great river and its tributaries.

In the year 1877 Little Chief’s band of Cheyenne, while being, taken south, was for some time detained at Fort Lincoln, N. D., and among them were the mother of old Elk River (born about 1786) and part of her family. During their stay at Fort Lincoln, this old woman took her daughter and granddaughter about to various points not far from the post, and with laughter and tears showed them the well-known places where, as a girl, she had played and worked. She said that at the time of which she then told, her group of Cheyenne lived in a permanent village on the east bank of the Missouri river and planted there. In the large houses of this village, the grandmother said, there were often a considerable number of people, two or three or four families. She explained that the small house sites in the permanent villages were menstrual lodges, or those occupied by old women who lived alone, as often they did when they were old, and believed that they had not long to live. Elk River was a Suhtai.

White Bull, a Northern Cheyenne, born 1834, declares that in 1832 when High Back Wolf, Limber Lance, and Bull Head went to Washington, the first Cheyenne delegation to visit the seat of the Government, the Cheyenne were still farming on and near the Missouri. It was soon after the death of High Back Bear in 1833 that an increasing number of the Missouri River Cheyenne began to take to a wandering life and to give less attention to farming and some of them to go south. Up to this time many Cheyenne and many Suhtai were planting on the Missouri river. The different camps of Cheyenne, and of Suhtai, were sometimes on one side of the Missouri river and sometimes on the other. On the other hand, Cheyenne and Sioux tradition declares that there were Cheyenne far west of the Missouri river 150 years before that date.

We know comparatively little of the methods and ways of life of this tribe in very early days. No longer ago than the summer of 1918 a Cheyenne woman casually mentioned to me that fifty years ago all Cheyenne women knew how to weave baskets for general uses from a certain grass (Eleocharis sp.) and that she herself knew how to weave.

From the many suggested Cheyenne village sites, of which I have written, and from others of whose existence nothing is known, but which I suspect may be found if carefully looked for, there may be recovered archaeological material which may throw much light on the manners and customs of the primitive Cheyenne.

Citations:

- Minnesota Historical Society Collections, vol. i, p. 242.[

]

- S. R. Riggs, Contributions to North American Ethnology, vol. ix, p. 193.[

]

- Smithsonian Report (Wash., 1873), p. 402.[

]

- Minnesota Historical Society Collections, vol. ill, p. 284.[

]

- Minnesota Historical Society Collections, vol. I, p. 119.[

]

- St. Paul Daily Press, August 5, 1863.[

]

- Report to the Secretary of War of U. S. Indian Affairs (New Haven, 1822), pp. 251, 254, 366.[

]

- Extracts from Capt. Mackay’s Journal and others. Proceedings of the State Historical Society, Wisconsin (1915), p. 208.[

]

- See War Dept. Map, Capts. D. P. Heap and William Ludlow (1875), and Sectional Map of South Dakota, Rand, McNally & Co. (Chicago, 1889).[

]

- War Map, Dept. Capts. D. P. Heap and William Ludlow, 1875.[

]

- Les Bourgeois de la Compagnie du Nord-Ouest, 1st series (Quebec, 1889), p. 377.[

]

- Washington Irving, Astoria (London, 1836), vol. 11, 69.[

]

- Contributions to North American Ethnology, vol. ix, p. 194.[

]

- Handbook of Indian Tribes, vol. i, p. 251.[

]

- Lewis and Clark Original Journals, Atlas Map 2.[

]

- Lewis and Clark Original Journals, vol. i, p. 195[

]

- Perrin du Lac, Voyage dans les deux Louisianes, &c. (Paris and Lyon, 1805), p. 259: “Sement pres de leur village du mais et du tabac, qu’ils viennent recolter au commencement de I’automne.”[

]