The tribe which, from the time of Washington’s visit to the Ohio, in 1753, down to their removal to the West, played so important a part under the name of Wyandots, but who were previously known by a name which French write Tionontates; and Dutch, Dinondadies, have a history not uneventful, and worthy of being traced clearly to distinguish them from the Hurons or Wyandots proper, of whom they absorbed one remnant, leaving later only a few families near Quebec, to represent the more powerful nation.

Champlain penetrated to the country of the Hurons; and the Tionontates, are mentioned by the nickname given them by the French traders: Petuneux, that is, Tobacco Indians, from their raising large quantities of it. Ever a thrifty, commercial, and agricultural people, they were almost the only instance of a tribe raising any crop for sale; and down to this day, they have continued to bargain shrewdly. 1

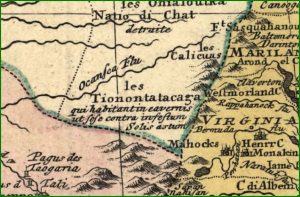

The Recollect missionary, Father Joseph Le Caron, remained in a Huron village while Champlain accompanied a war party against the Iroquois of Western New York; and on the explorer’s return, early in 1616, proceeded with him to the country of the Tionontates. “They have,” says Champlain, ” large villages and palisades, and plant Indian corn,” 2 besides the tobacco, from the cultivation and trade in which, as we remarked, they took their name.

Their distance from the Huron towns is not stated by Champlain, Sagard, or Le Clercq. In later Jesuit Relations it is stated variously, doubtless according to the place of the writer, an, eight leagues, twelve or fifteen leagues, and two days’ journey 3. Their language seems to have been identical with 4 the Hurons, no allusion being made to any dialectic difference, as in the case of the Neutral Nation 5.

They were, at this period, at peace with the Hurons, but this had not always been the case. According to Jerome Lalemant 6, long and bloody wars had divided them; but a peace was finally made, which proved a lasting one, and in 1640 it had been recently renewed and a confederation formed against common enemies.

After the visit of Champlain and Le Clerq 7, we have no further allusion to them, till the establishment of the Jesuit mission, after Canada was restored by the English. In 1635, Brebeuf mentions them as Khionontatehronons 8. Two years after, in April, 1637, they were visited by Father Charles Garnier, who laid the foundation of a mission; but the medicine men who had opposed Le Caron, were no less suspicious of Garnier. An epidemic which ravaged the country, was attributed to the witchcraft of the French, and a beaver robe was offered to the missionaries to propitiate their favor and induce them to stop the disease 9.

Father Isaac Jogues and Charles Garnier, who visited it, and founded there the Mission of the Apostles, in 1640, found the nation in nine towns, Ehwae, being the chief one. Their account of the tribe is not very full 10. The next year, when Garnier returned with Father Peter Pijart, he found that Ehwae had been destroyed by a hostile force, but, unfortunately, we are not told who the enemy was 11 12. The missions were too widespread, and the missionaries, for a time, now merely paid stated visits to the Tionontate villages 13, and for some years we find no further details as to their history.

“At last, however,” says Father Garnier in a letter of August, 1648, “this nation of the Petun, 14 having asked the missionaries partly to instruct them, and partly to make themselves formidable to their enemies, by the report that spread that they had French in their country, Father Garreau and I were sent. He, to instruct the Algonquins residing in that nation of the Petun, although of a different language from our Hurons, and I, to instruct the Hurons.” 15

They accordingly, in October, 1646, took up their residence at Ekarenniondi or St. Mathias, a town composed of Tionontates and Algonquins.

This would show that the nation had been reduced to two towns, Etharita, or St. John’s, of the Wolf tribe, and Ekarenniondi, or St. Mathias, of the Stag. 16

The Hurons Join the Tionontates in the Blue Mountains

In 1648 we first find mention of Tionontates killed by Senecas 17. A third mission was established in 1649; but all was soon to close. On the destruction of most of the Huron towns, in 1648, many of the survivors fled to the mountains of the Tionontates 18, and this soon drew the warlike Iroquois upon them. 19 20

In December, 1649, the Wolf town, called by the missionaries St. John, containing about 500 or 600 families, being informed by the missionaries on the Huron island, that an Iroquois force was in the field, bent on attacking one of them, resolved to await them, but after waiting some days, set out to attack them on their march. Unfortunately they took a different route from that by which the enemy were advancing; and during their absence the Iroquois surprised the town, massacring the old, the women and children 21. The site was initially identified by the similarity of unique bear mandible artifacts there with those from pre-Dispersal Petun sites, particularly at Craigleith, Ontario 22, and after giving all to the flames, retired in haste. The missionaries remained for a time at their Huron mission, but in 1650, led a party of their converts to Quebec, and abandoned the Huron territory. A band of Tionontates attempted to follow them, but were cut off by the Iroquois 23. The tribe, then wasted by war, fled to the island of Michilimackinac, as Perrot and Dablon seem to agree in assuring us 24, then to the Noquet Islands 25, and then, says Perrot, to Mechingan 26, with the Ottawas, thenceforth for many years their inseparable companions. Grown careful by repeated disasters, they cultivated the ground carefully, and kept well to their fort, so that when no Iroquois war-party came, the Tionontates and Ottawas defied them; and the assailants were soon glad to make offers of peace, so as not to be pursued. Yet the Ottawas tried to poison them, and the Chippeways and Illinois soon after cut off the whole party. This was apparently in 1655.

Their position was however too exposed, the fugitives crossed to the other side of Lake Michigan, descended the Wisconsin, and mounting the Mississippi, to the river of the Iowas, sought refuge among the Dacotas of the Mississippi. These tribes as yet ignorant of fire-arms, regarded the Hurons with a wonder which they returned with contempt. After the Ottawas had settled in peace at Isle Pelee, the Hurons attacked the Dacotas, but being defeated and harassed in turn by this tribe, retired to the sources of the Black River, the Ottawas continuing their retreat to Chagoimegon. The Tionontates or Hurons, as they are generally called by writers at this period, were then about sixty leagues from Green Bay, it was supposed 27, and invited their old missionary, Father Menard, from Chagoimegon; but the veteran perished in an endeavor to reach their town, on Black River 28. When Allouez raised his chapel at Chagoimegon, the Tionontates removed thither to enjoy the advantages of French trade and French protection against the Sioux and Iroquois, who still pursued them. Their village lay on one side of the mission, the Ottawa village on the other 29. At Chagoimegon they subsisted on maize and the produce of their fisheries, relying but little on hunting 30. They numbered from four to five hundred souls, but from long mingling with pagan tribes had almost lost all traces of Christianity. Their missionary, the celebrated Father Marquette, endeavored not only to reclaim them, but to create peace; he sought to win the Sioux, and sent them pictures as symbols, being as yet unable to address them. Still keeping up the Sioux war, a party of one hundred Hurons, entered the Dacota territory, but were surrounded and retreating to the narrow necks of land into which the country is cut up, were all taken actually in nets, by the Dacotas. To prevent the escape of the Hurons, they stretched nets with bells across each isthmus, and as the Hurons in the dark attempted to escape they betrayed themselves and were all taken but one, called by the French “Le Froid” 31.

On this the Sioux armed, and sending back Father Marquette‘s presents, declared war 32. The Ottawas retired to Ekaentouton, and the Hurons to Mackinaw 33, founding the Mission of St. Ignatius.

The Petun Nation

In 1672, Marquette wrote to Dablon: “The Hurons, called Tionontateronnon or Petun nation, who compose the Mission of St. Ignatius, at Michilimakinong, began last year, near the chapel, a fort inclosing all their cabins.” Their number, he states elsewhere, at 380 34. From what is said in the Relation of 1671-2, that the Hurons settled on the island, one may infer that this fort and chapel were there, nothing appearing in the Relations of 1672-3, to indicate a change.

They soon, however, transferred their town to the mainland: and this village is that from which the discoverers of the Mississippi set out, and to which the remains of Marquette were finally so strangely brought, as described by Dablon 35.

In 1676 or 7, the Senecas sent an embassy to the Hurons, bearing very rich presents, offering aid against the Sioux, but really, as the missionaries believed, to allure them to New York 36.

The Recollect Father Hennepin, who visited their town in 1679, with La Salle, – his pioneer vessel, the Griffin, bearing them to that spot, – describes the Huron village as surrounded with palisades 25 feet high, and very advantageously situated on a promontory, towards the great point of land opposite Missilimakinak 37.

Their intercourse with the Senecas now became frequent 38; when the murder of Annanhac, a Seneca chief, by an Illinois, in their presence, in 1681, exposed them to war 39, they treated with them separately, drawing on themselves the reproaches of Frontenac 40.

Sasteretsi was regarded at this time as head chief or king, and all was done in his name. Ten canoes bearing his word, Soiioias or the Rat being the speaker, attended an Indian congress at Montreal, Aug. 15, 1682. The other chiefs mentioned, are Ondahiastechen 41, and Oskouendeti 42.

In 1686, Scoubache, one of their number, betrayed his countrymen, so that seventy, who were hunting in the Saginaw country, fell into the hands of the Iroquois and were carried off 43.

The active Dongau, however, wished to win the Tionontates and Ottawas to the English cause, claiming Michilimackinac as English territory. He sent traders there in 1686, who were escorted by the Senecas for a distance, were well received by the Hurons, who took them on their way to prevent any French pursuit 44. On their return, he sent another party, comprising some French deserters, under Colonel McGregory, to winter with the Senecas and induce them to restore the Huron prisoners, and at the same time open a trade in the spring. A second party was to follow 45. The Tionontates, on their side, won by the persuasions of the Senecas, and the cheapness of English goods, could scarcely be restrained from removing en masse to New York, but the missionaries and French officers succeeded in retaining them 46. McGregory fell into the hands of de la Durantaye, who made the English all prisoners, and the Tionontates, whom he led, fought bravely beside Denonville, in his battle with the Senecas, July 13, 1687 47.

The second English party, also led by Tionontate prisoners as guides, fell into Tonti‘s hands, and through the Tionontates, endeavored to induce Tonti‘s Indians to murder him; they refused 48 thus to espouse the English cause.

In the winter of this year, a party sent out from Michilimackinac under Saentsouan, passing Detroit on the 2d of December, on their way to the Seneca country. When they had been out ten days, they surprised an Iroquois encampment, killing or taking sixty-two, only two escaping of the whole camp. The Tionontates lost three, and returned with eighteen prisoners 49. 50

The Rat (aka Soiioias, Souaiti, Kondiaronk, Adario)

The Rat, called in the dispatch of Frontenac 51, Soiioias, and Souaiti; by Charlevoix, Kondiaronk; by La Hontan, Adario, probably a fictitious name based on the last, also led a war-party against their ancient foes 52 early in 1688, but the peace made by Denonville was not agreeable to him, and he craftily resolved to produce a rupture. Knowing that deputies were to proceed to the French to confirm the peace, he attacked them, killing several of the party and taking the rest prisoners. The surprised ambassadors explained the nature of their errand, when the Rat pretended that he had been sent by Denonville to cut them off treacherously; and, as if regretting his unfortunate part in it, urged them to revenge it by a decisive blow. As he lost one in the action, he took a Shawnee slave in his stead, and on returning to Mackinac, gave him to the French, who executed him, and the Rat sent one of the Iroquois prisoners to the Seneca country, to attest this confirmation of French treachery.

By this artful design he roused the spirit of the Iroquois, who burst in their fury on Montreal Island, with some New Yorkers, and butchered over two hundred of the French settlers with every form of brutality 53.

The Baron

But while the Rat, in his hatred of the Iroquois would keep up the war at all hazards, another Tionontate chief, the Baron, was a decided friend of the English and Five Nations. He dissembled, however, and in July, 1696, represented the village in a congress of the Indians at Montreal, professing all eagerness to carry on the war 54; but he had, in reality withheld the braves of the village from taking the war-path, and had, on the contrary, sent his son and thirty braves with nine belts to the Senecas 55.56 In 1695, he gave great trouble to La Motte Cadillac, by his efforts in favor of the Iroquois 57, and soon after attempted to exercise the influence of a seer, by bringing a package of skins as the message and present of an imaginary centenarian hermit, at Saginaw 58. La Motte prevented their renewing the Sioux war, but the Baron‘s son set out with a party to Seneca, to return some Iroquois prisoners and fourteen belts, to say: “Our Father has vexed us, he has long deceived us. We now cast away his voice; we will not hear it any more. We come without his participation to make peace with you to join our arms. The chief at Michilimackinac, has told us lies; he has made us kill one another. Our Father has betrayed us. We listen to him no more” 59.

Deputies of the Iroquois then proceeded to Michilimackinac, bearing Anick’s belt, an invitation of the English, addressed through the Iroquois to the western tribes to eat White Meat, that is, to massacre the French 60.

These belts were accepted in spite of all Cadillac‘s efforts 61, and the Hurons with their Algonquin allies, gave belts and presents in return, among other things a red stone calumet of remarkable beauty and size. A trade was immediately opened and the Iroquois soon after departed laden with furs. But the Indian mind was easily swayed. Cadillac convened the tribes, they forsook their allies, an Ottawa war-party started in pursuit of the Iroquois, whom they overtook and cut to pieces, killing thirty, drowning as many, and returning loaded with scalps, prisoners, and plunder 62. Among the prisoners were some Hurons, who were sent back to their village 63. This affair, however, caused a bitter feeling between the Hurons and Ottawas, which led to fatal results; the conceited and tyrannical Cadillac inflaming still more the breach he had created. The Hurons were the first to suffer, one of their parties being massacred by the Ottawas, a son of the Rat falling a victim 64.

The Rat, however, remained firm, and when the Baron retired to the Miamis, he learned that an Iroquois force was coming to join him. Against this force he took the field, and by pretending flight, drew them into disorder, then turned and completely defeated them, killing, among the rest, five of the greatest Seneca captains 65.

The Baron‘s withdrawal from Mackinaw closed for a time the negotiations with the Iroquois; and after he settled among the Mohawks, with his adherents, he no longer figures in history 66. It is said that the whole Dinondadie nation would have joined the Iroquois, if the latter had consented to their forming a village apart, as a sixth nation, but that the League steadily refused to do this.

The tribe now in the name of Sasteratsi their king, professed their allegiance to the French crown 67, and when the Senecas threatened the Ottawas, and cut off some French at Mackinaw, in 1698, the Hurons, on both occasions, took the field and cut the assailants to pieces 68.

La Motte Cadillac‘s great project was to establish a post at Detroit, and, in 1701, he began Fort Pontchartrain at that place, inducing a portion of the Hurons to accompany him, which they did readily, from their hostility to the Ottawas 69. The missionary at Mackinaw, Father Stephen de Carheil, was averse to the change, and believed that the liquor trade of the new post would prove their ruin; but thirty more followed, in 1703, leaving only twenty-five at Mackinaw 70. Before 1706 all had departed, and the missionaries, burning their house, descended to Quebec 71, the presence of a Franciscan missionary at Detroit, dispensing with their services there.

The Hurons were lured to Detroit by great plans of the visionary Cadillac. He was going to make Frenchmen of them all; and as the Jesuits had tried to convert first and civilize after, he attempted to civilize first and convert after. His plan was to enroll the braves as soldiers, dress them in French uniform, and subject them to discipline; to dress and educate the children, teaching them the French language. A fine oak house, forty feet by twenty-four, was built for the head chief, on the river side overlooking the Huron village. This was the first installment, but it is needless to say that the Huron regiment never figures in the military annals of France.

Soon after their removing to Detroit they took up the hatchet against the English 72; but on the peace, attended the general council of the tribes at Montreal, their chief, Kondiaronk, being received with honor, and rendering essential service to the French. Before the close of the council, he fell sick, but continued to attend till he was so prostrated that he died the day of his removal to the hospital. As he was greatly esteemed by the French, and bore the rank of captain in the army, he was interred with the greatest honors, the governor and all the officers attending the funeral, which opened with sixty soldiers, followed by sixteen Hurons, the clergy, the coffin, with the chapean, sword, and gorget, to mark his rank; his brothers and children succeeded as mourners, followed by the governor 73.

The chief who next acquired the ascendency in the tribe, was one called by the French Quarante Sols 74. He favored the English and Iroquois, and, like the Baron, endeavored to open a trade through the Miamis, finding the French goods exceedingly dear 75.

The English influence led, in 1703, to an attempt to burn the fort, and completely divided the western tribes. The Hurons, still jealous of the Ottawas, sided against them, in 1706, when the latter attacked the Miamis at Detroit, and in the confusion killed the Recollect Father Constantine, and a soldier, but when Cadillac subsequently marched against the Miamis, they joined him, though strongly suspected of plotting to cut off the French 76. Their war parties were, however, sent principally against the Southern tribes; the Cherokees, Choctaws, and Shawnees, whose territories they reached by way of Sandusky, the Scioto, and Ohio 77.

In 1710, when the western tribes hesitated to take up the hatchet against the English, the Dinondadies set them an example, by taking the field 78, and when, two years after, the Foxes besieged du Buisson, in Detroit, in May, 1712, they came with the other allies from their hunting-ground, and after dislodging the Foxes from their first camp, cut them to pieces in that to which they subsequently retreated. In the long and stubborn fight, the Hurons lost more heavily than any other of the tribes 79.

A memoir on the Indians between Lake Erie and the Mississippi, in 1718, published in the New York Colonial Documents 80, says, that the Hurons were about three furlongs from the French fort, and adds: “This is the most industrious nation that can be seen. They scarcely ever dance, and are always at work; they raise a very large amount of Indian corn, peas, and beans; some grow wheat. They construct their huts entirely of bark, very strong and solid; very lofty, and arched, like arbors. Their fort is entirely encircled with pickets, well redoubled, and has strong gates. They are the most faithful nation to the French, and the most expert hunters that we have. Their cabins are divided into compartments, which contain their Misirague, and are very clean. They are the bravest of all the nations and possess considerable talent. They are well clad. Some of them wear close overcoats. The men are always hunting, summer and winter, and the women work. When they go hunting in the fall, a goodly number of them remain to guard their fort.”

Their number at this time is represented 81 as one hundred fighting men.

Charlevoix, represents their village, in 1721, as being on the American side, near Fort Pontchartrain, but not as near it as the Pottawatomie village. Sasteretsi, the king, was a minor, his uncle acting as regent. There was no resident missionary; although the tribe, especially the female portion, were anxious to have once more a clergyman able to instruct them in their own language. Like the writer last quoted, he bears testimony to the industry of the Tionontates-Hurons. Comparing them to the other tribes, he calls them more steady, industrious, laborious, and provident: “Being more accustomed to farming, he thinks of what is advantageous; and by his labor, is able not only to support himself without aid, but also to maintain others. He does not indeed do it gratuitously, for among his good qualities disinterestedness is not to be numbered” 82.

In the earlier accounts, as we have stated, the families of this tribe are given as the Wolf and Deer; but Charlevoix, who here styles the tribe the Nation of the Porcupine, says that their totems are the Bear or Deer, Wolf, and Turtle, thus making their families correspond with the great Iroquois families. Yet, he remarks, that in a treaty at Mackinaw, their signature was a beaver. De la Chauvaguerie, in 1736 83, gives the totems of the Turtle, Bear, and Plover; but Father Potier, in 1745, gives the families, or as he styles them, bands, as follows: Oskennonton, the Deer; Andiarich, the Turtle, and llannaariska, the Wolf; the Deer being subdivided into Esontennonk, Eangontrounnon, Hatinnionen; the Turtle into Enneenstenronnon, Eronisseeronnon, Atieeronnon, Entieronnon; and the Wolf, into the Hatinaa- riskwa, Hatindesonk, and the Hotiraon and Tiataentsi—the two last, forming one band, making ten in all. These are, apparently, the ten tribes into which Finley 84, says, the nation is divided. He gives the totems, as Bear, Wolf, Deer, Porcupine, Beaver, Eagle, Snake, Big Turtle, Little Turtle, and Land Turtle. The chieftaincy or kingship, under the name of Sasteretsi, was in the Esontennonk down to recent times; Finley says, till Wayne’s victory, in 1794, in which the Deer tribe was almost annihilated, after which chiefs were taken from the Porcupine family.

In June, 1721, Tonti convened the Tionontates in council, to announce that he was about to stop the liquor trade, and to invite them to join in the war against the Foxes. To the former, they made no objection, admitting that it was a wise step; but they were averse to the war, as they had been too often sacrificed, hurried into needless wars, which the French concluded without consulting their interest in the least 85. They did, however, take up the hatchet, in 1728, and served faithfully in Ligneris’ expedition against the Foxes 86, and again in 1732 87.

In this last year, we see indices of a quarrel with the Senecas, who endeavored again to arouse the Ottawas against the Tionontates; but the latter were too powerful, and from having been a sorry band of fugitives, assumed a bold attitude, and began to assert claims, which our government recognized, and paid for largely. The tribe, which at Mackinaw had no ground, which had none at Detroit, now claimed all the territory between Lake Erie and the Ohio, as their hunting ground; and when the Shawnees spoke of settling there, warned them to plant their villages on the south of the river, if they would avoid trouble 88. De la Chauvignerie, in 1736, estimated their strength at two hundred fighting men.

When the war broke out, in 1744, the Tionontates of Detroit, took up the hatchet, and sent out many war-parties against the English 89, but soon began to change sides. Their hunting-ground, as we have seen, was the present State of Ohio, and Sandusky was [heir central point, doubtless, from the pure water which induced them to give it that name. The other points of wintering were Tiochiennendi. Cedar River, Karenouskaron, Pointe Pelee, Riviere de la Oarriere, Sagoendaon, Huron River, Kerendiniondi, Pointe au Rocher, Otsikwoinhiae, Totontaraton, Tousetaen, Te ostiesarondi, Karhora, Wahiague, Karindore, Otsandouske intae, Tsiawiske in Sandusky, Sonnioto 90, Touwatetiori, Etsoundoutak, and Agaague, on the Ohio. While scattered thus, they were in frequent communication with the English and their Indian allies, and soon showed an hostility to the French. A village under Nicholas, a war-chief, in Wyandot, Orantondi, had almost formed at Sandusky, and here they suddenly fell upon five French traders, whom they killed and robbed 91. The hostility to the French then began to spread among the tribes of the West, encouraged by belts from the confederates in New York. A plan was formed, by the Hurons, to massacre the French at Detroit, and had well-nigh succeeded. As it was usual to let them sleep inside the fort, the pirators resolved to enter as usual, and during the night, each one was to kill the people of the house where he was. Fortunately, for the French, a squaw overheard this, and sent information to M. de Longuenil, the commander, who baffled their project 92.

The missionary Father Potier on this retired from the village in Bois Blanc island to Detroit 93.

A manuscript of this missionary contains a census of the tribe, in 1745, and also in 1746, from which it appears that in the former year, the small village 94 contained nineteen cabins, the large village 95, fifteen, with eight in the fields, and four on White river, Sasteretsi, being the king or chief of the Deer band; Angwirot, of the Turtle; and Taechiaten, of the Wolf; Nicholas, la Foret, Tonti, Le Brutal, Bricon, and Matthias, being prominent men. The next year, he enumerates only seventeen in the small village; fifteen, in the large village; eight at Etionontout, and four, as before, on White River, or Belle Riviere. Of the whole tribe, nine are put down as Iroquois, among them Bricon, a leading man; four, as half-breed Ottawas; one Pottawatomie, two Abnakis, six Choctaws, fifteen Foxes, two Chickasaws.

The Indians of Sasteretsi‘s and Taechiaten‘s bands, immediately endeavored to exculpate themselves; but de Longueuil would not listen to them, referring them to the governor. Fearing a war, they sent down deputies, the occasion of the return of Mr. Belestre with some Lorette Hurons enabling them to do so safely. Sasterets and Taechiaten, went in person, and in a council, at Montreal, on the 9th of August, 1747, asked for the return of Father de la Richardie. This was granted, and they set out in September, having been delayed by the sickness of Taechiaten, who in fact died on the way back. The murder seems to have been disclaimed, and a promise made to insist on the surrender of the murderers; but this was no easy matter, Nicholas being powerful, and gathering many around him, besides influencing those at Detroit. Much depended on the influence of Father Richardie; but his arrival and mission at Sandusky, seem to have had but little influence. A Huron, named Tohake, who had been supposed dead, but who really had been at New York, returned, and began to treat with the western tribes. Thus encouraged, Nicholas sent his belts to the various nations to urge a general rising. The Ottawas and Pottawatomies, who had promised Longueuil to destroy the Huron village on Bois Blanc island, deferred it on various pretexts; the Miamis seized and plundered the French among them, and French settlers and traders were cut off in all directions.

Longueuil was now in a most critical position. The English had so far gained the tribes that all the western posts were in danger, the English having in fact offered rewards for the heads of the several commanders. Longueuil could only temporize; he kept demanding the surrender of the murderers from Nicholas, and at last, in December, 1747, Nicholas, Ortoni, and Anioton or Le Brutal, came to make peace, surrender the English belts, and make reparation. Pardon was granted on the strange condition, that they should bring in two English scalps for each of the murdered Frenchmen. This was agreed to, but during the negotiation a motley band – Onondagas, Senecas, and Delawares – but led by a Huron, of Detroit, fired on a French canoe, wounding and, as was supposed, killing three persons. They were pursued, brought in, and the Onondaga killed on the spot, by the incensed French. The rest were imprisoned, but the Seneca committed suicide, and the others were given in January, 1748, to Scotache and Quarante Sous, Sandusky Hurons, as the Senecas and Delawares, of the Ohio, threatened to take vengeance on both French and Hurons 96.

Still influenced by the English, Nicholas gathered his band on the White River, twenty-five leagues from Detroit, with one hundred and nineteen warriors, men, women, and baggage, burning his fort and village at Sandusky 97. but many returned to Detroit.

During all these proceedings, Sasteretsi remained faithful. Delegates of his band went to Quebec, and while the sachems remained to treat, the braves took the war-path against the English. After a time matters became quieted, many removed to Sandusky, where Father de la Richardie established a mission, at the town of Sunyendeand, on a creek of the same name 98.

The intrigues of the English to gain the western tribes, so steadily carried on from Dongan’s time, showed the French government that nothing could save them but a line of forts at some intermediate line. When Niagara, Presqu’ile, Venango, and Du Quesne arose, the fidelity of the western Indians was acquired.

The Senecas, Shawnees, and Dinondadies, now first called in English accounts Wyandots, at first protested against these forts, and met the Pennsylvania authorities at Carlisle; but the vigor of the French determined their choice. Beaujeu, in 1755, led a force, in which the Wyandots were conspicuous, to annihilate Braddock.

At the conclusion of that war, Col. Bouquet estimated their numbers at three hundred men.

When Pontiac rallied the tribes around him, to avoid the extinction which menaced them, the Wyandots, of Detroit, in spite of the efforts of their missionary, Father Potier, forgot their old English friendship and new allegiance, and joined the patriot forces of the chieftain, fighting better than any other tribe that joined him 99. Sandusky was full of traders, too many indeed to attack, so that there the wily Wyandots revealed the plot, assuring the English that their only chance of life was to become their prisoners, as such they could protect them from the other Indians. The credulous English consented, were disarmed, bound, and it is almost needless to say, butchered 100. One only, Chapman, whom a frantic act at the stake, made the Indians suppose to be insane, escaped 101.

Before the siege of Detroit ended, however, those of the villages near the town, asked for, and obtained peace; but, when Dalyell arrived fresh from the destruction of the Wyandot towns near Sandusky, and the ravaging of the fields, they opened a fire on his vessel, which was returned, but the English lost fifteen killed. They then attempted to lure the English to their town, hut failing then, soon had their rage satisfied in the battle of Bloody Bridge, where the devastator of their village fell 102. A party soon after attacked the schooner Gladwyn, killed the commander, and gained the deck, but fled when the mate called out to blow her up.

Dalyell had, as we have seen, ravaged the Sandusky towns; and when the Wyandots of Detroit made peace with Sir William Johnson, at Niagara, in July, 1764, those of Sandusky held aloof, but when Bradstreet approached, they sent a deputation, promising to follow him to Detroit, if he would not attack them. To this he at once consented 103, and both Wyandot towns met him in council, in September, at Detroit.

Between this and the period of the Revolution, all seem to have centered at Sandusky, where the trader, whose estimate is preserved in the Madison papers, estimated them, in 1778, as able to send out one hundred and eighty fighting men. They were then hostile to the Americans, and influenced by Hamilton.

[box]The majority of this work is based on a manuscript by John Gilmary Shea: An Historical Sketch of the Tionontates or Dinondadies, Now called Wyandots, published in volume 5 of the Historical Magazine pp. 262-269. To this we have added some notes from Charles Garrad from his Shea’s Petun Historical Sketch. And finally we have interspersed some informational notes by Dennis Partridge.[/box]

Citations:

- Charles Garrad: That the Petun are so named “from their raising large quantities of tobacco” is now rejected. This source of this statement is the Identification Table attached to Champlain‘s 1636 map which, in fact, was not by Champlain. It is now believed that the Petun grew no more, nor less, tobacco than was usual for an Iroquoian group. That “they were almost the only instance of raising a crop for sale” is rejected. The tobacco grown by the Petun was for personal and shamanistic use, not a crop for sale.[↩]

- Charles Garrad: The statement attributed to Champlain concerning “large villages and palisades”, while not challenged, was not by Champlain but by the anonymous contributor to the Identification Table to the 1636 map. Champlain himself did not mention tobacco.[↩]

- Rel. 1636, p. 105; Rel. 1637, p. 163; Rel. 1648, p. 46[↩]

- some of[↩]

- Rel. 1636, p. 53; Rel. 1640, p. 05[↩]

- Rel. 1640, p. 95[↩]

- Charles Garrad: Le Clerq” (Le Clercq) is an error for Father Joseph Ie Caron, as is later shown.[↩]

- Rel. 1635, p. 33[↩]

- Rel. 1638, p. 34; Rel. 1639, p. 88[↩]

- Rel. 1640, pp. 35, 51, 95[↩]

- Rel. 1641, p. 69[↩]

- Charles Garrad: The Mission of the Apostles commenced in 1639. Ehwae was attacked but could not have been entirely destroyed as it continued to function for a while[↩]

- Rel. 1642, p. 88[↩]

- the ordinary French term (in Champlain’s time) for tobacco was petun, which was the native word for the plant in one of the South American languages, adopted by the Portuguese and from them taken into French. Nicot, who in the sixteenth century introduced tobacco into France as a medicinal herb, called it nicotiane or herbe à la reine, after Catherine de Medici. Champlain, vol. 1, p. 78[↩]

- See, too, Rel. 1648, p. 61.[↩]

- Charles Garrad: The separation of the missionaries to two separate town did not mean that the Petun were reduced to those two towns. Both towns had at least one related satellite (?) village.[↩]

- Rel. 1648, p. 49[↩]

- Rel. 1649, p. 26[↩]

- Charles Garrad: The third mission was not “established” in 1649. The Mission of La Conception was the oldest Huron mission. In 1649 it moved from Ossossane to the Petun country. The Petun country has elevations that from a distance could appear to be mountains, but the Hurons did not move to the high lands, but to the villages on the flat lands below the Blue Mountain.[↩]

- We at AccessGenealogy are not certain we agree with Charles in his assumption of the area in which the Petun were living at the time the Huron’s joined them. We believe due to the many maps depicting the Tionontates as those who reside in caves in the mountains that they likely did live further into the Blue Mountains, or moved soon after the Hurons arrived.[↩]

- Charles Garrad: It is not accepted that the Iroquois massacred “the old, the women and children” because, in the absence of the men, these comprised the total population of the village. It is now believed that one of the purposes of the Iroquois raids was to capture women and children for forced adoption. These were heard during their forced march and the Jesuits later found them in the Iroquois country. The band of Tionontates who “were cut off by the Iroquois” while supposedly attempting to follow the French to Quebec may well have been the husbands of the captured women hoping to re-unite with them by going voluntarily to the Iroquois. The migration route of the post-1650 a.d. Petun, with which this paragraph concludes, and continues onto page 264, is beyond the temporal and geographic scope of these notes, but it is relevant to mention that in 1969 the 1652 Petun and Odawa settlement among the Noquet or Potawatomi Islands at Green Bay, Wisconsin, was found on Rock Island ((see: Mason, Ronald J. Great lakes Archaeology, page 398, New York: Academic Press. 1981.[↩]

- see: Mason, Ronald J. Rock Island, especially pages 181-184. Kent State University Press. 1986.[↩]

- Rel. 1651, p. 5[↩]

- Rel. 1671, p. 37; Rel. 1672, p. 36; Moeurs des Sauvages, p. 161; Colden’s Five Nations, p. 28[↩]

- Rel. 1672, p. 36[↩]

- Moeurs des Sauvages, p. 161[↩]

- Rel. 1660, p. 27[↩]

- Rel. 1663, p. 21[↩]

- Rel. 1667, p. 15[↩]

- Rel. 1670, p. 86[↩]

- Perrot[↩]

- Rel. 1672, p. 36[↩]

- Rel. 1671, p. 39[↩]

- see his letter in Discovery and Exploration of the Mississippi Valley, p. 62[↩]

- Rel. 1673-9, p. 58[↩]

- Rel. 1676-7, p. 47[↩]

- Decouverte dans l’Am., Sept. in Voyages au Nord, vol. ix., p. 124[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 164[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., pp. 175, 176[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 188[↩]

- Burnt tongue[↩]

- the Runner[↩]

- O’Callaghan’s Col. Doc., N. Y., vol. ix., p. 293[↩]

- Doc., N. Y., vol. ix., p. 297[↩]

- Doc., N. Y., vol. ix., p. 308[↩]

- Doc., N. Y., vol. ix., p. 325; vol. v., 487[↩]

- Colden’s Five Nations, p. 73[↩]

- Colden’s Five Nations, p. 75[↩]

- La Hontan, vol. ii., p. 111[↩]

- La Hontan, vol. ii., p. 115, in his letter of May, 1698, says: That the Hurons and Ottawas had each a village separated by a simple palisade, though the latter were building a fort. The Jesuit house and church being next to the Huron in an inclosure by themselves. Hist. Mao. Vol. V. 34[↩]

- O’Callaghan’s Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 178[↩]

- La Hontan, vol. ii., p. 117[↩]

- La Hontan, vol. ii., p. 191; O’Callaghan’s N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., pp. 391, 393, 402; Colden’s Five Nations, p. 87; Charlevoix, vol. i., p. 535; Perrot, 282[↩]

- O’Callaghan’s Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 478[↩]

- Colden’s Five Nations, p. 114; Charlevoix, vol. ii., p. 156[↩]

- In July, 1698, when Fletcher met the deputies of the Five Nations, at Albany, an Oneida chief informed him that it was proposed by all the Five Nations to make peace with the Dinondiulies: that the Senecas had undertaken it, and had taken belts of wampum from the other nations to confirm it. To this they desired the governor’s consent, and asked him to send a belt, which he did. – Colden’s Five Nations, p. 155.[↩]

- Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 605[↩]

- Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 607[↩]

- Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 619[↩]

- Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 644[↩]

- Charlevoix, vol. ii., p. 162[↩]

- Charlevoix, vol. ii., p. 164[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 646[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 648[↩]

- Charlevoix, vol. ii., p. 212[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., pp. 670, 672[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix, p. 667[↩]

- Charlevoix, vol. ii., p. 224; N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 684[↩]

- D’Aigremont, in Sheldon’s Michigan, p. 289[↩]

- Sheldon’s Michigan, p. 104[↩]

- Charlevoix, vol. ii., p. 306[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 704[↩]

- Charlevoix, vol. ii., p. 276[↩]

- Forty Pence[↩]

- Charlevoix, vol. ii., p. 291; N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 743[↩]

- Charlevoix, vol. ii., p. 323[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 886[↩]

- Charlevoix, vol. ii., p. 358[↩]

- Charlevoix, vol. ii., p. 373; Sheldon’s Michigan, p. 298[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 887[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 888[↩]

- Hist. Nouvelle France, vol. ii., p. 259[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 1058[↩]

- Wyandot Mission, p. 34[↩]

- Charlevoix, Hist. N. F., vol. ii., p. 259; Sheldon’s Michigan, p. 320[↩]

- Crespel, in Shea’s Perils of the Ocean and Wilderness, p. 141; Smith’s Wisconsin, vol. i., pp. 339-345[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 1035[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. ix., p. 1035[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. x., p. 20[↩]

- ? Scioto[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. x., p. 114[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Documents, vol. x., pp. 83, 84[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. x, p. 116[↩]

- near the fort?[↩]

- on Bois Blanc island?[↩]

- N. Y. Col. Doc., vol. x, p. 191. See, also, pp. 128, 138-142, 145, 150-2, 160-7[↩]

- Col. Doc., vol. x., 181[↩]

- meaning Rocktish[↩]

- Parkman’s Pontiac, p. 215[↩]

- Parkman’s Pontiac, citing Loskiel[↩]

- Heckwelder, Hist. Ind. Nat., p. 250[↩]

- Heckwelder, Hist. Ind. Nat., p. 278[↩]

- Parkman’s Pontiac, p. 464[↩]