An accurate classification of the American Indians, either founded upon dissimilarities in the language of different tribes, or upon differences in physical peculiarities, is impossible, particularly in treating of the scattered and wandering people of the far west. The races vary by such slight shades of distinction, and such analogies exist between their languages, that even where the distinction is perfectly evident in the nation at large, the line of demarcation can with difficulty be drawn. In other instances, the same nation, when divided into separate clans, inhabiting districts of dissimilar nature, and resorting to different modes of life, will be found, in the course of one or two generations, to present the appearance of distinct races.

Perhaps it would be wiser to accept the popular divisions, whether derived directly from the natives, or established by those most familiar with them, than to attempt, any refined distinctions. In an essay upon natural history, or in researches into historical antiquities, a particularity might be useful or necessary, which in an outline of history and description would be but perplexing and tedious.

A vast wilderness at the west, upon the Missouri and the upper western tributaries of the Mississippi, is inhabited by the various tribes allied to the Sioux or Dahcota. One of the earliest accounts given of these people, then known as the Naudowessies, is to be found in the Travels of Captain Jonathan Carver, who spent the winter of 1766-7 among them. Of later observations and descriptions, by far the most interesting and complete are contained in the published letters of Mr. George Catlin, accompanied as they are by spirited and artistic portraits and sketches of scenery.

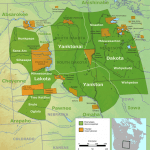

Those of this race known as the proper Sioux, soi disant Dahcota, are mostly established upon the river of St. Peter and in the country adjacent. Some of the eastern tribes are more or less agricultural, but the others are wild haulers like their brethren of the far west. The Sioux were divided, a century since, into the following eight tribes: the Wawpeentowas, the Tintons, the Afracootans, the Mawhaws (Omawhas), and the Schians, all of whom dwelt in the prairie country, upon the St. Peter, and three other clans of the then unexplored region to the westward. The Assinaboin anciently belonged to the same stock.

By Mr. Gallatin the race is divided as follows:

- The Winnebago, of Wisconsin.

- The Sioux proper, or Dahcota, and the Assinaboins.

- The Minetari and tribes allied to them.

- The Osages, and other kindred tribes, farther south. (Pritchard’s Natural History of Man). The Minetari are held to include the Crows and the Mandan.

The Sioux, Mode of Life

The Sioux proper, known among themselves and by other Indian tribes as Dahcota, are one of the most extensively diffused nations of the west. From the Upper Mississippi, where they mingle with the northern race of Chippewa, to the Missouri, and far in the northwest towards the country of the Blackfeet, the tribes of this family occupy the boundless prairie.

Those living on the Mississippi and St. Peter’s rely partially, as we have mentioned, upon agriculture, and their proximity to the white settlements has changed, and too often degraded their native character. The more distant tribes, subsisting almost entirely upon the flesh of the buffalo, clothed with skins, and using the native weapons of their race, still remain in a state of rude freedom and in dependence. Graphic descriptions of their wild life, their skill and dexterity in the chase, and innumerable amusing and striking incidents of travel, and portraitures of private and natural character, are to be found scattered through the pages of Catlin s interesting narrative.

One of the most remarkable and touching traits of character described by this author, as observable among the Sioux, is the strength of maternal affection. Infant children, according to the common custom of western Indians, are carried, for the first six or seven months of their existence, strapped immovably to a board, the hands and arms being generally left at liberty. A hoop protects the child s face from injury in case of a fall, and the whole apparatus is often highly ornamented with fringe and embroidery. This pack or cradle is provided with a broad band, which is passed round the forehead of the mother, sustaining the weight of the child pendent at her back. Those who have been most familiar with this mode of treatment generally approve of it as best suited to the life led by the Indian, and as in no way cruel to the child. After the infant has in some degree acquired the use of its limbs, it is freed from these encumbrances, and borne in the fold of the mother s blanket.

“If the infant dies during the time that is allotted to it to be carried in this cradle, it is buried, and the disconsolate mother fills the cradle with black quills and feathers, in the parts which the child s body had occupied, and in this way carries it around with her wherever she goes for a year or more, with as much care as if her infant were alive and in it; and she often lays or stands it against the side of the wigwam, where she is all day engaged with her needle-work, and chatting and talking to it as familiarly and affectionately as if it were her loved infant, instead of its shell, that she was talking to. So lasting and so strong is the affection of these women for the lost child, that it matters not how heavy or cruel their load, or how rugged the route they have to pass over, they will faithfully carry this, and carefully, from day to day, and even more strictly perform their duties to it, than if the child were alive and in it.” (Letters and Notes of George Catlin)

What appears, at first glance, to be one of the most revolting and cruel customs of the migratory Sioux tribes (a custom common to other western nations,) is the exposure of the old and infirm to perish, after they have become unable to keep up with the tribe. We are told, however, that dire necessity compels them to this course, unless they would more humanely, it is true at once put an end to the lives of such unfortunates. The old sufferer not only assents to the proceeding, but generally suggests it, when conscious that he is too weak to travel, or to be of any further service among his people. With some slight protection over him, and a little food by his side, he is left to die, and be devoured by the wolves.

Certain tribes of this nation, far up the Missouri, are in the habit of performing various ceremonies of self-torture in their religious exercises, somewhat analogous to those of the Mandan, but seldom, if ever, are they carried to such an extent as we have described in treating of that tribe.

In the Sioux country, at the southern extremity of the high ridge, called the Coteau des Prairies, which separates the head-waters of the St. Peter s from the Missouri, is situated the far-famed quarry of red pipe-stone. Pipes of this formation are seen throughout the whole of the west, no other material being considered suitable. The district was formerly considered as a sort of neutral ground, where hostile tribes from far and near might harmoniously resort to supply the all essential want of the Indian. Those versed in the mysteries of Indian heraldry have deciphered the distinguishing marks and escutcheons of a great number of western nations, inscribed upon adjacent rocks. Of late years the Sioux have affected a monopoly in the products of this quarry, and it was not without the most vehement opposition that Mr. Catlin and his companions, led by curiosity to visit the remote and celebrated place, were enabled to make their way through the Indian settlements fallen in with on the route.

A Sioux Brave

Signifies “He that inflicts the first wound”

Throngs of dusky warriors, at these stopping-places, would assemble to discuss, with great heat and excitement, the true motives of the strangers. The general impression seemed to be that the travelers were government agents, sent to survey the locality for the purpose of appropriation, and one and all expressed a determination to perish rather than relinquish their rights to this, their most valued place of resort.

The stone is obtained by digging to a depth of several feet in the prairie, at the foot of a precipitous wall of quartz rocks. The whole geological formation of that district is described as exceedingly singular,, and the pipe-stone formation is, itself, entirely unique. This material is “harder than gypsum, and softer than carbonate of lime; ” it is asserted that a precisely similar formation has been found at no other spot upon the globe. The component materials, according to the analysis of Mr. Catlin s specimens, by Dr. Jackson, of Boston, are as follows: “water, 8.4; silica, 48.2; alumina, 28.2; magnesia, 6.0; carbonate of lime, 2.6; peroxide of iron, 5.0; oxide of manganese, 0.6.”

The Indians use the stone only in the manufacture of pipes; to apply it to any other use they esteem the most unheard of sacrilege. From the affinity of its color to that of their own skins they draw some fanciful legend of its formation, at the time of the great deluge, out of the flesh of the perishing red men. They esteem it one of the choicest gifts of the Great Spirit.

The following extracts from the speeches of some Sioux chiefs, through whose village Mr. Catlin passed on his way to the quarry, may serve to exemplify the veneration with which the stone was regarded.

“You see,” said one, (holding a red pipe to the side of his naked arm,) “that this pipe is a part of our flesh. The red men are a part of the red stone. ( How, how !)” an expression of strong approbation from the auditors.

“If the white men take away a piece of the red pipe-stone, it is a hole made in our flesh, and the blood will always run. We cannot stop the blood from running. (How, how!) The Great Spirit has told us that the red stone is only to be used for pipes, and through them we are to smoke to him. (How !)”

The next speaker pronounced the stone to be priceless, as it was medicine. Another, after a preliminary vaunt of his own prowess, and worthiness to be listened to, proceeded: “We love to go to the Pipe-Stone, and get a piece for our pipes; but we ask the Great Spirit first. If the white men go to it, they will take it out, and not fill up the holes again, and the Great Spirit will be offended. (How, how, how!)”

Another ” My friends, listen to me! what I am to say will be truth. (‘How!’) I bought a large piece of the pipe-stone, and gave it to a white man to make a pipe; he was our trader, and I wished him to have a good pipe. The next time I went to his store, I was unhappy when I saw that stone made into a dish! (‘Eugh!’)

“This is the way the white men would use the red pipe stone if they could get it. Such conduct would offend the Great Spirit, and make a red man’s heart sick. (How, how!)”

Many of the pipes in use among the Sioux, and formed of this material, are shaped with great labor and nicety, and often in very ingenious figures. Those intended for calumets or pipes of peace, are gorgeously decorated, but even those in ordinary use are generally made as ornamental as practicable. The cavity is drilled by means of a hard stick, with sand and water; the outer form, with the carvings and grotesque figures, is worked with a knife.

Various narcotic herbs and leaves, where tobacco is not to be obtained, are used for smoking, under the name of “knick-knick;” the same term is used among some southern Indians to denote a mixture of tobacco and sumach leaves.

In the far west, both among the Sioux and other wild tribes, as the hunt of the buffalo is by far the most important occupation of the men, we will devote some little space to a description of the habits of the animal, and the native modes of pursuing and destroying it. The buffalo, or bison of America, is found at the present day throughout no small portion of the vast unsettled country between our western frontier and the Rocky Mountains, from the southern parts of Texas to the cold and desolate regions of the north, even to latitude fifty-five degrees. Nowhere are these animals more abundant, or in a situation more congenial to their increase, and the development of their powers, than in the western country of the Sioux. During certain seasons of the year, they congregate in immense herds, but are generally distributed over the country in small companies, wandering about in search of the best pasturage.

They have no certain routine of migration, although those whose occupation leads to a study of their movements can in some localities point out the general course of their trail; and this uncertainty renders the mode of subsistence depended upon by extensive western tribes of Indians exceedingly precarious.

The most valuable possessions of these races, and the most essential in the pursuit of the buffalo, are their horses. These useful auxiliaries are of the wild prairie breed, extensively spread over the western territory, the descendants of those originally brought over by the Spaniards in the sixteenth century. They are small, but strong and hardy, and superior in speed to any other of the wild animals of the prairie. Numbers of them are kept about the encampment of the Indians, hobbled so as to prevent their straying away. Upon the open prairie the bison is generally pursued upon horseback, with the lance and bow and arrow. The short stiff bow is little calculated for accurate marksmanship, or for a distant shot: riding at full speed, the Indian generally waits till he has overtaken his prey, and discharges his arrow from the distance of a few feet.

The admirable training of the horse, to whom the rider is obliged to give loose rein as he approaches his object and prepares to inflict the deadly wound, is no less notice able than the spirit and energy of the rider.

Such is the force with which the arrow is thrown, that repeated instances are related of its complete passage through the huge body of the buffalo, and its exit upon the opposite side. This near approach to the powerful and infuriated animal is by no means without danger. Although the horse, from instinctive fear of the buffalo’s horns, sheers off immediately upon passing him, it is not always done with sufficient quickness to avoid his stroke. The” hunter is said to be so carried away by the excitement and exhilaration of pursuit, as to be apparently perfectly reckless of his own safety; trusting entirely to the sagacity and quickness of his horse to take him out of the danger into which he is rushing.

The noose, or lasso, used in catching wild horses, is often left trailing upon the ground during the chase, to afford the hunter an easy means .of securing and remounting his horse in case he should be dismounted, by the attack of the buffalo or otherwise.

In the winter season it is common for the Indians of the northern latitudes to drive the buffalo herds from the bare ridges, where they collect to feed upon the exposed herbage, into the snow-covered valleys. The unwieldy beasts, as they flounder through the drifts, are easily over taken by the hunters, supported by their snow-shoes, and killed with the lance or bow. Another method, adopted by the Indians, is to put on the disguise of a white wolf skin, and steal unsuspected among the herd, where they can select their prey at leisure. Packs of wolves frequently follow the herds, to feed upon the carcasses of those that perish, or the remains left by the hunters. They dare not attack them in a body, and are consequently no objects of terror to the buffaloes; but, should an old or wounded animal be separated from the company, they collect around him, and gradually weary him out and devour him.

When buffalo are plenty, and the Indians have fair opportunity, the most astonishing and wasteful slaughter ensues. Besides the ordinary methods of destruction, the custom of driving immense herds over some precipitous ledge, where those behind trample down and thrust over the foremost, until hundreds and thousands are destroyed, has been often described.

Even at seasons in which the fur is valueless, and little besides a present supply of food can be obtained by destroying the animal which constitutes their sole resource, no spirit of forethought or providence restrains the wild hunters of the prairie. Mr. Catlin, when at the mouth of Teton river, Upper Missouri, in 1832, was told that a few days previous to his arrival, a party of Sioux had returned from a hunt, bringing fourteen hundred buffalo tongues, all that they had secured of their booty, and that these were immediately traded away for a few gallons of whiskey.

The author goes, at considerable length, into a calculation of the causes now at work, which must, in his opinion, necessarily result in the entire extinction of these animals, and the consequent destitution of the numerous tribes that derive support from their pursuit. According to his representations, we “draw from that country one hundred and fifty or two hundred thousand of their robes annually, the greater part of which are taken from animals that are killed expressly for the robe, at a season when the meat is not cured and preserved, and for each of which skins the Indian has received but a pint of whiskey!

Such is the fact, and that number, or near it, are annually destroyed, in addition to the number that is necessarily killed for the subsistence of three hundred thousand Indians, who live entirely upon them.”

When this extermination shall have taken place, if, in deed, it should take place before other causes shall have annihilated the Indian nations of the west, it is difficult to conceive to what these will resort for subsistence. Will they gradually perish from sheer destitution, or, as has been predicted, will they be driven to violence and plunder upon our western frontier?

See Further: