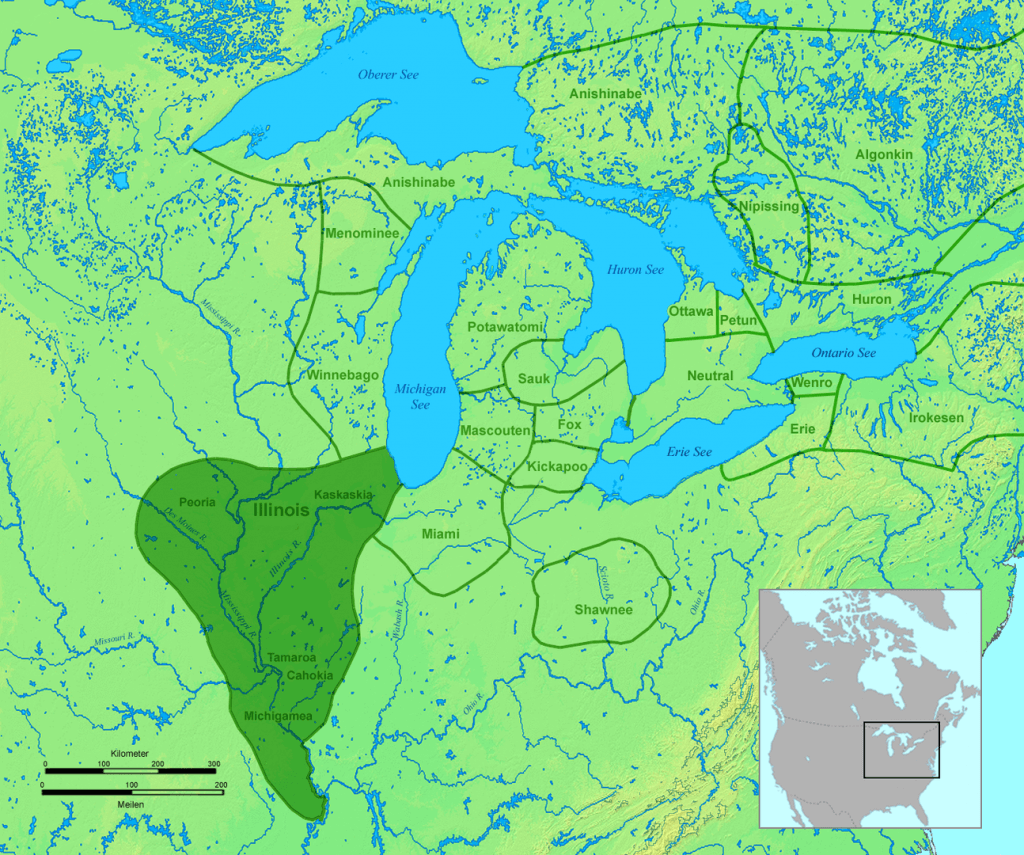

Illinois Indians, Illinois Confederacy (Iliniwek, front ilini ‘man’, iw ‘is’, ek plural termination, changed by the French to ois). A confederacy of Algonquian tribes, formerly occupying south Wisconsin, northern Illinois, and sections of Iowa and Missouri, comprising the Cahokia, Kaskaskia, Michigamea, Moingwena, Peoria, and Tamaroa.

The Jesuit Relation for 1660 represents the Illinois tribe as living southwest of Green Bay, Wis., in 60 villages, and gives an extravagant estimate of the population, 20,000 men, or 70,000 souls. The statement in the Jesuit Relations that they came from the border of a great sea in the far west arose, no doubt (as Tailhan suggests), from a misunderstanding of the term “great water,” given by the Indians, Which in fact referred to the Mississippi. Their exact location when first heard of by the whites can not he determined with certainty, as the tribes and bands were more or less scattered over southern Wisconsin, northern Illinois, and along the west bank of the Mississippi as far south as Des Moines river, Iowa. The whites first carne in actual contact with them (unless it be true that Nicollet visited them) at La Pointe (Shaugawaumikong), where Allouez met a party in 1667, which was visiting that point for purposes of trade. In 1670 the sane priest found a number of them at the Mascoutin village on upper Fox river, some 9 miles from where Portage City now stands, but this band then contemplated joining their brethren on the Mississippi. The conflicting statements regarding the number of their villages at this period and the indefiniteness as to localities render it difficult to reach a satisfactory conclusion on these points. It appears that some villages were situated on the west side of the Mississippi, in what is now Iowa, yet the major portion of the tribes belonging to the confederacy resided at points in northern Illinois, chiefly on Illinois, river. When Marquette journeyed down the Mississippi in 1673 he found the Peoria and Moingwena on the west side, about the mouth of Des Moines river. On his return, 2 months later, he found them on Illinois river, near the present city of Peoria. Thence he passed north to the village of Kaskaskia, then on upper Illinois river, within the present Lasalle county. At this time the village consisted of 74cabins and was occupied by one tribe only. Hennepin estimated them, about l680, at 400 houses and 1,800 warriors, or about 6, 500 souls. A few years later (1690-94) missionaries reported it to consist of 350 cabins, occupied by 8 tribes or bands. Father Sebastian Rasles, who visited the village in 1692, placed the number of cabins at 300, each of 4 “fires,” with 2 families to a fire, indicating a population of about 9,000 perhaps an excessive estimate. The evidence, however, indicates that a large part of the confederacy was gathered at this point for awhile. The Kaskaskia at this time were in somewhat intimate relation with the Peoria, since Gravier, who returned to their village in 1700, says he found them preparing to starts., and believed that if he could have arrived sooner “the Kaskaskians would not thus have separated from the Peouaroua [Peoria] and other Illinois.” By his persuasion they were induced to stop in south Illinois at the point to which their name was given.

The Cahokia and Tamaroa were at this time living at their historic seats on the Mississippi in south Illinois. The Illinois were almost constantly harassed by the Sioux, Foxes, and other northern tribes; it was probably on this account that they concentrated, about the time of La Salle’s visit, on Illinois river. About the same time the Iroquois waged war against them, which lasted several year, and greatly reduced their numbers, while liquor obtained from the French tended still further to weaken them. About the year 1750 they were still estimated at from 1,500 to 2,000 souls.

The murder of the celebrated chief Pontiac, by a Kaskaskia Indian, about 1769, provoked the vengeance of the Lake tribes on the Illinois, and a war of extermination was begun which, in a few years, reduced them to a mere handful, who took refuge with the French settlers at Kaskaskia, while the Sauk, Foxes, Kickapoo, and Potawatomi took possession of their country. In 1778 the Kaskaskia still numbered 210, living in a village 3 miles north of Kaskaskia, while the Peoria and Michigamea together numbered 170 on the Mississippi, a few miles farther up. Both bands had become demoralized and generally worthless through the use of liquor. In 1800 there were only about 150 left. In 1833 the survivors, represented by the Kaskaskia and Peoria, sold their lands in Illinois and removed west of the Mississippi, and are now in the northeast corner of Oklahoma, consolidated with the Wea and Piankashaw. In 1885 the consolidated Peoria, Kaskaskia, Wea, and Piankashaw numbered but 149, and even these are much mixed with white blood. In 1905 their number was 195.

Nothing definite is known of their tribal divisions or clans. In 1736, according to Chauvignerie 1 the totem of the Kaskaskia was a feather of an arrow, notched, or two arrows fixed like a St. Andrew’s cross; while the Illinois as a whole had the crane, bear, white hind, fork, and tortoise totems.

In addition to the principal tribes or divisions above mentioned, the following are given by early writers as seemingly belonging to the Illinois: Albivi, Amonokoa, Chepoussa, Chinko, Coiracoentanon, Espeminkia, and Tapouara. In general their villages bore the names of the tribes occupying them, and were constantly varying in number and shifting in location.

The Illinois are described by early writers as tall and robust, with pleasant visages. The descriptions of their character given by the early missionaries differ widely, but altogether they appear to have been timid, easily driven from their homes by their enemies, fickle, and treacherous. They were counted excellent archers, and, besides the bow, used in war a kind of lance and a wooden club. Polygamy was common among them, a man sometimes taking several sisters as wives. Unfaithfulness of a wife was punished, as among the Miami, the Sioux, the Apache, and other tribes, by cutting off the nose of the offending woman, and as the men were very jealous, this punishment was often inflicted on mere suspicion.

It was not the custom of the Illinois, at the time the whites first became acquainted with them, to bury their dead. The body was wrapped in skins and attached by the feet and head to trees. There is reason, however, to believe, from discoveries that have been made in mounds and ancient graves, which appear to be attributable to some of the Illinois tribes, that the skeletons, after the flesh had rotted away, were buried, often in rude stone sepulchers. Prisoners of war were usually sold to other tribes.

According to Hennepin, the cabins of the more northerly tribes were made like long arbors and covered with double mats of flat flags or rushes, so well sewed that they were never penetrated by wind, snow, or rain. To each cabin were 4 or 5 fires, and to each fire 2 families, indicating that each dwelling housed some 8 or 10 families. Their towns were not inclosed.

The villages of the confederacy noted in history are:

- Cahokia (mission)

- Immaculate Conception (mission)

- Kaskaskia

- Matchinkoa

- Moingwena

- Peoria

- Pimitoui

Further Information on the Illinois Tribe:

- The Illinois

An article on the Illinois Confederacy from Strong, William Duncan. Indians of the Chicago Region, With Special Reference to the Illinois and the Potawatomi, published in Fieldiana, Popular Series, Anthropology, no. 24. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History. 1938.

Citations:

- Chauvignerie, N. Y. Doc. Col. Hist., ix, 1056-1855,[

]