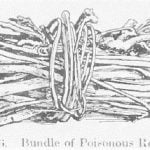

Quite naturally fishing plays an important part in the life of the Yuchi who have almost always lived near streams furnishing fish in abundance. Catfish, cu dj?á, garfish, pike, cu cpá, bass, cu wadá, and many other kinds are eagerly sought for by families and sometimes by whole communities at a time, to vary their diet. We find widely distributed among the people of the Southeast a characteristic method of getting fish by utilizing certain vegetable poisons which are thrown into the water. Among the Yuchi the practice is as follows. During the months of July and August many families gather at the banks of some convenient creek for the purpose of securing quantities of fish and, to a certain extent, of intermingling socially for a short time. A large stock of roots of devil’s shoestring (Tephrosia virginiana) is laid up and tied in bundles beforehand. The event usually occurs at a place where rifts cause shallow-water below and above a well-stocked pool. Stakes are driven close together at the rifts to act as barriers to the passage and escape of the fish. Then the bundles of roots (Fig. 6) are thrown in and the people enter the water to stir it up. This has the effect of causing the fish, when the poison has had time to act, to rise to the surface, bellies up, seemingly dead. They are then gathered by both men and women and carried away in baskets to be dried for future use, or consumed in a feast which ends the event. The catch is equally divided among those present. Upon which an occasion, as soon as the fish appear floating the surface of the water, the Indians leap, yell and set to dancing in exuberance. If a stranger comes along at such a time he is taken by the hand and presented with the choicest fish.

As the fish are taken out they may be cleaned and salted for preservation, or roasted and eaten on the spot. A favorite method of cleaning fish the instant they are caught, is to draw out the intestines with a hook through the anus, without cutting the fish open. A cottonwood stick shaved of its outer bark is then inserted in the fish from tail to head. The whole is thickly covered with mud and put in the embers of a fire. When the mud cracks off the roast is done and ready to eat. The cottonwood stick gives a much-liked flavor to the flesh.

In the way of a comparison, we find that the Creeks use pounded buckeye or horse chestnuts for the same purpose. Two men enter the water and strain the buckeye juice through bags. The Creeks claim that the devil’s shoestring poison used by the Yuchi floats on the water, thus passing away down stream while the buckeye sinks and does better work. It is probable, however, that neither method of poisoning the streams is used exclusively by these tribes, but that the people of certain districts favor one or the other method, according to the time of year and locality. The flesh of the fish killed in this way is perfectly palatable.

It frequently happens that the poison is not strong enough to thoroughly stupefy the fish. In such a case the men are at hand with bows and arrows, to shoot them as they flounder about trying to escape or to keep near the bottom of the pool. The arrows used for shooting fish are different from those used in hunting. They are generally unfeathered shafts with charred points, but the better ones are provided with points like cones made by pounding a piece of some flat metal over the end of the shaft (Fig. 4, a). The men frequently go to the larger streams where the poison method would not be as effective, and shoot fish with these heavy tipped arrows either from the shores or from canoes. Simple harpoons of cane whittled to a sharp point are used in the killing of larger fish which swim near the surface, or wooden spears with fire-hardened points arc thrown at them when found lurking near the banks.

Formerly the Yuchi made use also of basket fish traps. These were quite large, being ordinarily about three feet or more in diameter and from six to ten feet in length. They were cylindrical in shape, with one end open and an indented funnel-shaped passageway leading to the interior. The warp splints of this indenture ended in sharp points left free. As these pointed inward they allowed the fish to pass readily in entering, but offered an obstruction to their exit. The other end of the trap was closed up, but the covering could be removed to remove the contents. Willow sticks composed the warp standards, while the wicker filling was of shaved hickory splints. The trap was weighted down in the water and chunks of meat were put in it for bait.

Gaff-hooks for fishing do not seem to have been used, according to the older men, until they obtained pins from the whites, when the Yuchi learned how to make fish hooks of them. Prior to this, nevertheless, they had several gorge-hook devices for baiting and snagging fish. A stick with pointed reverse barbs whittled along it near the end was covered with some white meat and drawn, or trolled, rapidly through the water on a line. When a fish swallowed the bait the angler gave the line a tug and the barbs caught the fish in the stomach. Another method was to tie together the ends of a springy, sharp-pointed splinter and cover the whole with meat for bait. When this gorge device was swallowed the binding soon disintegrated, the sharp ends being released killed the fish and held it fast. Lines thus baited were set in numbers along the banks of streams and visited regularly by fishermen.