The Sioux massacre of the whites in Minnesota in August, 1862, is one of the bloodiest that has ever occurred in the history of the Indian races in North America. In the earlier periods of the country, the frontier settlements were constantly exposed to. Indian depredations, and their destruction at any time seemed probable from their comparative feebleness and remoteness from succor; but that the savage tribes should rise against the whites almost within sight of our populous cities, our railroads and steamboats, was not dreamed of by any one.

The Sioux massacre, had it occurred in a time of peace, would have moved the nation more profoundly than any event in our history, but coming as it did in the midst of one of the most fearful civil wars the world has ever seen, it lost half its horrors. When our fathers, brothers and sons were falling by the tens of thousands in our very midst, the slaughter of a few hundred settlers on our frontier seemed comparatively a small evil.

A Warlike Tribe

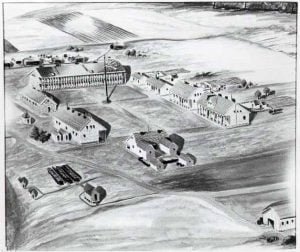

The Sioux, or Dacotah Indians, as they have been known from time immemorial, have always been a warlike tribe, but as civilization advanced and encroached upon them, their savage character gradually changed, and for years they had lived at peace with their white neighbors. They had step by step receded before the tide of emigration, selling their lands to the government, until by the last treaties, especially the one ratified in 1860, they yielded all their possessions in Iowa, Dakota and Minnesota, except a tract a hundred and fifty miles long, on the Minnesota river. In accordance with these treaties, a large amount of money and goods was annually delivered to them, and an agent of the government resided among them to superintend the transaction of all public business. For the sake of convenience two stations were established for this purpose, one fourteen miles above Fort Ridgely, on the Minnesota river, called the “Lower,” or “Redwood Agency,” and the other at the mouth of the Yellow Medicine River, known as the “Upper,” or “Yellow Medicine Agency.” A part of the nation, perhaps a hundred families, had adopted civilized customs, lived in frame-houses, dressed in coats and pantaloons, attended churches and schools, had plows, harrows, and all the agricultural implements, and seemed fast merging into civilization. The other portion, however, lived in huts on the prairie, and retained their savage customs and habits.

A few miles above the Yellow Medicine were churches and schools in charge of Rev. S. R. Riggs and Dr. Williamson, who for a long time had been missionaries among them. At Lac qui Parle was another school under the care of Rev. Mr. Huggins, while trading posts were established at various points. Besides the whites and Indians, a numerous race of half-breeds had sprung up. A good road ran through the reservation, with eighteen well-constructed bridges. Some three thousand acres of this fertile region had been fenced and planted, while saw and corn-mills and brickyards were established at the agencies.

Civilization Commenced

But although matters seemed in this thriving, prosperous condition, there had been at various times, indications of an outbreak. The large annuities paid them by the government furnished tempting bait to unscrupulous traders and adventurers, who managed from time to time to make large fortunes at the expense of the Indian. On two different occasions $2,900 that had been placed on a table in payment to some of the chiefs, was picked up by a half-breed and given to a white man, and that was the last ever seen of it. Receipts were obtained on the promise of furnishing horses, guns, &c. which were never paid. Once a man by the name of Hugh Tyler, took $55,000 as pay due him, as he alleged, for getting a treaty through the Senate. The $166,000 which the Indians were to receive for ceding their lands north of the Minnesota, they never saw or received a penny of for four years, or until the very year of the massacre, and then but $1,500 worth of goods were sent, and even this was deducted from the money due them under a former treaty. The Indians, indignant at the fraud, refused for a long time to receive them, and finally did so only after the government had agreed to make it right with them.

Injustice Of Our Government

Things had gone on in this way until at the outbreak the annuities amounted to scarcely fifteen dollars a piece of the 6,200 that composed the tribe. This was not sufficient to keep them from starvation, and the winter previous to the massacre numbers actually died from want, and many others only lived by eating their horses and dogs. Other and slighter causes, but such as an Indian keenly feels, incensed them against the whites, and nothing but their powerlessness kept them from violence long before. The outbreak of civil war among us naturally excited in their hearts the belief that their day of revenge was at hand. Said a famous Cherokee chief, many years ago, when speaking of the wrongs done his nation, “One of these days you will be at war among yourselves, and then when you are weakened, we will come down on you like the mountain wolf on the fold, and tear you in pieces.” Such thoughts stirred the hearts of the Sioux braves. Besides, they did not escape the war excitement that filled the land. Recruiting stations were in their midst, and companies of half-breeds were organized for the army. This also showed to them the desperate straits of the government for men, and its weakness. Added to all, the wildest rumors spread among them of the sacking of our cities by the south, the capture of Washington, and even the President. All these things tended to kindle the sullen desire for revenge which for a long time had smoldered in their breasts, into a belief that their time for action had come.

About the first of July the young men of the nation formed a secret association, called the “Soldier’s Lodge,” the object of which was to control matters when any thing of great importance to the nation occurred. Yet all this did not alarm the whites, and the traders who had come to despise the Indians, would tell them as Foulon did the mob of Paris when they said they were starving, to “Eat Hay.” The very night before the outbreak, a large council was held only fifteen miles from the lower agency, in which it was determined to go the next day to the Agency and demand the money due them, thence to Fort Ridgely, if refused, to St. Paul; and if necessary, to resort to violence to secure their rights. It will thus be seen that the whole nation was resting on the bosom of a volcano, which at any moment might burst forth in a deluge of fire.

Yet strange as it may seem, the whites reposed in perfect security; the wholesome fear, which kept the early settlers on the alert, had been laid to rest so long that it seemed impossible to rouse it. So complete was this delusion that the government agent, Mr. Galbraith, who visited the entire reservation just before the outbreak, spoke on his return with great satisfaction of the prosperous condition of affairs in the tribe.

Still, notwithstanding this apparent preparation of a sudden uprising, the time and manner of its occurrence seemed purely accidental.

Beginning Of The Massacre

On the first of August a party of twenty Indians went to the “Big Woods,” an extensive forest about eighty miles above the falls of St. Anthony, to hunt and get a wagon which a chief had left the previous winter with Captain Whitcomb. They separated on the way, some of them going towards Acton. These got into a quarrel a few days after, accusing each other of cowardice for being afraid of the whites. They finally separated, the larger number saying to four who went off by themselves, “You will see whether we are brave or not, for we are going to kill a white man.” Soon after, the four heard the others firing, and supposing they were shooting down whites, said they must kill some too, to show that they were equally brave. While they were debating the project, they came to Acton. Here they got into an altercation with three men named Jones, Baker and Webster. At length one of the Indians proposed they should go out and shoot at a mark, for the purpose of getting the guns of the whites discharged. They did so, when the Indians, after firing, carefully reloaded their guns, and consulting a moment together, appeared about to go away, when they suddenly turned and fired, shooting down Jones and his wife, and Baker and Webster. They then broke open Jones house, shot a young lady in it named Miss Wilson, and departed. Mrs. Webster, who was in a covered wagon, near by, and Mrs. Baker, who in her fright fell down cellar and was not noticed, escaped. This was the beginning of the massacre. The two women crawled forth to find their families weltering in blood. Hastening to the house of a Norwegian a few miles distant, they told their horrible story, and no man being at home, a boy was dispatched to Ripley, a distance of twelve miles, where a meeting was being held to raise a company of volunteers for the war. Seventy-five men were speedily assembled at the spot, and hearing that the other Indians were still in the neighbor hood, threatening violence, sent immediately to St. Paul, to the governor, for help.

The four Indians who had begun the massacre, hastened to the house of a Mr. Eckland, and stealing two horses, mounted them, two on each horse, and rode at a break neck pace to Shakopee’s village, into which they broke before daylight with a savage shout. The aroused natives were thrown into a state of the wildest excitement at the story they told. One thing they knew at once; these murderers must be given up, or the tribe held responsible; and the question arose what should be done, surrender them or fight, for there was no alternative. An excited, angry discussion arose in the council that was immediately called, but the relatives of the men declared they should not be given up. It was finally agreed, that as it had been decided in council the night previous, to go to Fort Ridgeley, and if necessary to St. Paul, and demand their annuity, they would start before daylight, and taking “Little Crow” in their way, consult with him respecting their future action. This was one of the most eloquent and crafty chieftains of the tribe. He had been to Washington, had become civilized, dressing like a white man, and living in a brick house, and regarded himself as a respectable citizen.

This wild delegation, mounted on horseback, started before daylight, and passing down the river, roused the Indian settlers on the way with their shouts and war cries. It needed but a spark to fire the tinder, and all along the way, other Indians jumped on their horses, and joined the wild cavalcade, that kept increasing as it advanced, till a hundred and fifty shouting, yelling madmen streamed along the road. They reached Crow s house before he was up, and the astonished chieftain, roused by the war cries that had so often stirred him in his youth, sat up in his bed. The next moment his room was filled with Indians, and wrapping himself in his blanket he asked the meaning of this strange gathering. Their story was soon told. They had now reached a pitch of excitement where counsel was useless. They did not want advice; they demanded that Crow should be their leader in a war against the whites. He saw at once that he must, or part forever with his tribe. Still, knowing the hazards he runs, the struggle within him for a few minutes was terrible. But his mind was soon made up, arid exclaiming, “I am with you,” leaped from his bed. Sending off swift couriers to other bands, he mounted his horse and led on the throng. It was agreed to fall on the Agency at once. But to make the blow sudden and overwhelming, they decided to enter the village quietly and in squads, as though nothing unusual was on foot, and stationing themselves at different points, wait a given signal, which was to be the discharge of a single gun from near the flag-staff, and then dash in and commence their work of blood. When all was ready the signal gun was fired, and in an instant the air was filled with war whoops, and the street with painted demons. The startled inhabitants ran to the doors of their houses and shops and stores, only to be shot down. The love of plunder soon drew them away from the work of slaughter, and many of the citizens succeeded in escaping. Among these was the Rev. Mr. Hindman, who lived in the lower part of the, town. He thus relates what he saw on this morning which ushered in the work of blood. “I arose early, expecting to go to Fairbault, had just finished breakfast, and was sitting outside, smoking a pipe, and talking with a mason about a job which he had just finished upon the new church which I was building. Presently I saw a number of Indians passing down, nearly naked, and armed with guns. The mason exclaimed, I guess they are going to have a dance.’ No, said Dr. Humphrey’s son, who was standing near us, they have guns and are not going to dance. Then I noticed, that instead of going by, they commenced sitting down on the steps of various buildings. About this time I heard the guns in the upper town. A man by the name of Whipple said, he guessed the Chippeways had come over, and they were having a battle. He then crossed the road to his boarding house. I soon noticed that the people at the boarding house, (who could see the upper stores,) were running down the bluff. Then four Indians came down the street. One of them left the others and went into the Indian farmer Prescott s house, and came immediately out. Frank Robertson, a young clerk in the employ of the government, followed him out, looking very pale. I asked him what was the matter. He said he did not know, but that the Indian told them all to stay in the house. He told me he thought there was going to be trouble, and started for Beaver Creek, a few miles above, where his mother lived.

“Soon White Dog, formerly president of the Farmer Indians, ran past, very much frightened. I asked him what the matter was, and he said there was awful work, and that he was going to see Waboshaw about it. Then Crow, with another Indian, went by the gate, and I asked Crow what was the matter. He was usually very polite, but now he made no answer, and regarding me with a savage look, went on towards the stable, the next building below.

Little Crow. Attack On The Lower Agency

Sparrowhawk that comes to you walking

A Sioux Chief

“Just before, Wagner ran by, and I asked him also what the trouble was. He said the Indians were going to the stables to steal horses, and that he was going there to stop them. I told him he had better not, as I was afraid there was trouble. He paid no attention to what I said. The next I saw was the Indians leading away the horses, and Wagner, and John Lamb and another person trying to prevent them. By this time Crow had reached there, and I heard him say to the Indians, “What are you doing? Why don t you shoot these men? What are you waiting for? Immediately the Indians fired, wounding Wagner, who escaped across the river to die, and killing Lamb and the other man.

“Then I found Miss West, and we started for the ferry. After we got about half way, she ran into a house, and I lost sight of her.

“Just as I got to Dickerson’s house, I came across a German who was wounded. I managed to get him down the hill and put him into a skiff, and we passed safely over and arrived at Fort Ridgeley about three o’clock. The people were crossing the ferry rapidly, and flying in every direction.”

A Noble Ferryman

The ferryman, Manley, a Frenchman, of low origin and among the most common and illiterate of the settlers, now showed himself to possess the elements of a true hero. Instead of flying with the rest, as he might have done and saved his life, he stayed manfully at his post, and unmoved amid the terror and panic around him, calmly passed backward and forward, carrying the fugitives over as fast as he could. This humble man, whom no one cared for, suddenly seemed to care for every body but himself. He arose to that loftiest point of self-sacrifice ever reached by man, to give his life for others. The firing steadily drew nearer, and the shots began to fall around him, yet as long as a fugitive stood on the shore, pleading for help, he kept returning until no more was to be saved. When the last man was over, and only infuriated Indians darkened the bank, a shot struck him, and he fell a true hero, though no poet ever sings his fame. The Indians, enraged that he had snatched so many from their grasp, swam across, and tearing out his bowels, cut off his head, hands and feet, and crammed them into the body and thus left him.

A few miles from the Agency several settlers with their families had gathered together previous to taking their flight. The Indians coming suddenly upon them poured a volley into their midst, which killed most of the men. The frightened women and children immediately huddled together in the wagons, and bending down drew their shawls and blankets over their heads to shut out the terrible doom that awaited them. “Cut Nose” then came up, and while two Indians sprang to the horses heads to prevent them from starting off, drove his tomahawk deliberately into the head of each. A smothered shriek from the survivors, followed each dull, crushing blow of the weapon, as they, powerless with terror, awaited their turn. Taking an infant from its mother s arms, Cut Nose handed it to the Indians, who drawing a bolt from the wagon, drove it through the body and pinned it to the fence. There, before the mother s eyes, they left it to writhe and die in agony. For a little while they stood and gloated over the mother s speechless misery at the awful spectacle, and then chopped off her arms and legs and left her to bleed to death. Twenty-five were thus massacred. When all had been disposed of, the savages kicked the mutilated bodies out of the wagons, and filling them with plunder, sent them back to be added to the other spoils, and then pushed on to other deeds of blood. Coming up to a farmer’s house in which were a husband and wife and two children, the father fired at them from the window. Before he could reload, they broke in with a yell. Finding no one within, the family having escaped by a back way, they pursued after and butchered the father, mother and son. The daughter, left alone, threw herself on the ground, pretending to be dead. The savages, after hacking the dead bodies, seized her by the feet to drag her off, when she instinctively moved to adjust her clothes. She was saved for a worse fate.

Flight And Death Of Dr. Humphreys

Dr. Humphreys, the physician, with three little children, the oldest only twelve years old, got off, and when two miles distant stopped at a house to rest. Being exhausted and thirsty, he sent h-s little boy a short distance for some water. While he was gone the Indians came up, and shooting his father, set fire to the house, and burned his mother and little brother alive. Frightened half to death he hid in some bushes. When the Indians left, he crept forth and found his father lying on the ground with his throat cut. Stupefied with fear he crawled back to his hiding place, where he remained till he was picked up in the afternoon by a band of soldiers sent from St. Peters. The Indians, having killed, captured or driven away all the whites, and filled the street with plunder, applied the torch to the buildings, and soon the summer sky was red with the conflagration. Couriers in the mean time had been dispatched to other bands, bearing the war cry.

Having finished the work of destruction at the Agency, the savages streamed down the river, slaughtering and burning as they went. As the fearful tidings spread, the terrified inhabitants fled from their homes, carrying away what household stuff they could collect, but in most cases they were met or overtaken and shot down. The pleading cries of women and children were unheeded, even when made to those whom they knew and had often befriended. Frenzied by their own deeds, and with all the long- slumbering fires of their savage nature fully aroused, they committed every act of atrocity that a devilish ingenuity could suggest. A farmer and his two sons were engaged in stacking wheat. Twelve Indians approached unseen to the fence, and from behind it shot all three. They then entered the farmer s house and killed two of the young children in the presence of their mother, who was ill with consumption, and dragged the mother and daughter miles away to their camp. There, in the presence of the dying mother, they stripped off the daughter’s clothes, fastened her back to the ground, and one by one violated her person, till death came to her relief. One Indian went into a house where a woman was making bread. Her small child was in the cradle. He split the mother’s head open with a tomahawk, and then placed the babe in the hot oven, where he kept it until nearly dead, when he took it out and beat out its brains against the wall.

Destruction Of Capt. Marsh

Children were nailed living to tables and doors, and knives and tomahawks thrown at them till they were killed. The womb of the pregnant mother was ripped open, the palpitating infant torn forth, cut into bits and thrown into the face of the mother. Whole families were burned alive in their homes. Such and similar deeds of horrid barbarity are recorded by Mr. Heard, who has published a book on the massacre, and by the newspapers of the times, all of which were verified. By noon the news reached Fort Ridgely, and Captain Marsh, of the Minnesota Volunteers, immediately started with forty-eight men in wagons, for the scene of destruction. On the way he met terrified fugitives, who told him to turn back, for the Indians outnumbered him three to one, and he was sure to be killed. He however kept resolutely on, and reached the ferry opposite the Agency, at sundown. The Indians came down to the opposite side of the river, and a parley was held through an interpreter. Marsh said he wished to come across and investigate matters. They declared he should not. The banks of the river were lined with bushes, and while the discussion was going on a large number of Indians secretly crossed and surrounded him, in concealed positions. Marsh, at first, was determined to cross at all hazards, but at length, at the earnest solicitations of friends, who declared it was certain death to make the attempt, he desisted. But the order to his men to wheel had hardly escaped his lips, when a sudden yell rose all around him, and the next moment a tremendous volley at close range, was poured into his little band. Nearly twenty fell at the first fire. With the survivors he stood his ground and returned the fire. But resistance was vain; his men dropped like leaves beside him, and seeing it was hopeless to continue the fight, he gathered nine men around him and fought his way out of the circle of fire. But after going two miles down the river, he found his way to the fort cut off, and seeing a spot where he thought the river could be forded, he ordered his men to plunge in, himself leading the way, with his sword and revolver lifted above his head. But he soon got beyond his depth, and sunk to rise no more. His nine followers reached the fort in safety, with the sad tidings of their loss.