Col. Sibley Marches to the Relief of Fort Ridgely and New Ulm

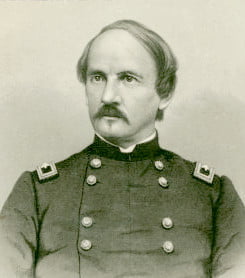

In the mean time Governor Ramsay had been rousing the state to arms. Luckily, several regiments of volunteers were in the state, nearly ready to depart for the war, so that in a few days 1,400 men had assembled at St. Peters. Col. Sibley was put at the head of these, and marched at once to the relief of New Ulm and Fort Ridgely. The former, we have seen, was evacuated before he reached it. Moving without opposition over the silent, desolated country, he reached the fort on the 28th of the month, much to the joy of the garrison.

Scattered over the prairie around, lay a vast number of black and decaying corpses, on which hogs and prairie foxes were rioting, and to bury these, and also to ascertain in what direction the Indians had gone, Col. Sibley sent out a detachment composed of a company of infantry and cavalry, commanded by Major Brown. This was the last day of August, Sunday. That day and the next they buried over two hundred bodies, and encamped at night at Birch Cooley, a place admirably adapted for a surprise. But water being convenient there, and not anticipating an attack; the command pitched their tents without fear. But Little Crow, who had moved with the Indian families up the river to the Yellow Medicine Agency, for greater safety, had been informed by his scouts that New Ulm was abandoned. A war party was immediately organized, with a long train of wagons, to go and secure the plunder. On their way down, the scouts discovered this detachment on the march. Watching its progress, to ascertain its destination, they saw with unbounded delight, it quietly camp at Birch Cooley. The unsuspecting whites corralled their horses, lit their camp fires, and lay down to rest. Just as the morning began to dawn, as the officer with the new relief was going the rounds, one of the sentinels saw, in the dim uncertain light, the tall grass waving in irregular lines up the ravine. He called the officer back to notice it. Just as he did so, an unearthly yell suddenly arose on every side, and the next moment a tempest of musket balls swept the encampment. Almost the entire guard fell at the first fire, and nearly a hundred horses dropped in their tracks. Had the Indians then charged, none would have been left to tell the tale of blood, for the whole camp was thrown into sudden confusion. But fortunately, they held back, and the men rallying, crawled forward, and sheltering themselves as best they could, behind the living and dead horses and wagons, poured in a destructive fire. They lay two together, and while one was firing, the other, with the point of his bayonet, dug a hole in the earth, ladling out the soil with his tin cup. Thus fighting and digging, they at last got well covered, and made their shots tell on the savages. They lay and fought in this way all day, but with their numbers steadily diminishing. That morning in the camp of Sibley, near the fort, the firing, though some twenty miles distant, was distinctly heard. Knowing at once that the detachment had been attacked, Sibley immediately dispatched a hundred and sixty men, with a six pound howitzer, to its relief. Sweeping rapidly over the prairies, they in the afternoon approached the scene of conflict. The Indians, hearing through scouts of their approach, left a few men at Birch Cooley, and hastened forward to attack them, before they could form a junction with their comrades. Colonel M. Phaill, in command, saw with great uneasiness, apparently more than a thousand Indians swarming down on his little band. He immediately opened on them with his howitzer, which kept them at bay, and dispatched a courier to Sibley for help. But this commander was already on the march. As the heavy boom of the cannon came rolling over the prairie, he ordered the tents to be struck and carried into the fort, and just at sunset put his whole force in motion. That night, at midnight, they came up to M. Phaill, and in the morning the whole moved forward. The Indians, ignorant of the arrival of the main army, came forth to meet them, when to their amazement they saw in the early sunlight, long lines of dazzling steel, moving over the prairie. “Oh! oh!” they cried, “there are five miles of white men coming,” and kept prudently out of range of our guns. Shaking their blankets and brandishing their guns, they scurried hither and thither, with loud war-whoops. The motley throng presented a picturesque appearance on the open prairie, in the early sunlight. Advancing in line of battle, firing as they went, the troops moved forward, and at last came in sight of the beleaguered camp, though not a living soul could be seen. Silent tents and slaughtered horses were all that was visible. As they came near, the survivors arose from their hiding places, and gazing a moment at the proud array, sent up a wild shout of delight, and leaped into the air. Exhausted, without water, and rapidly diminishing, a few more hours of delay would have left them at the mercy of the savages. Thirteen lay dead amid the tents, and sixty more were wounded. The former were buried on the spot, and the wounded placed on a bedding of grass pulled from the prairie, and carried to Fort Ridgely. Little Crow was not with this party, though he started with them. With a smaller band, he went to Acton, where he had a fight with another party of whites. When he returned to Yellow Medicine, and learned what a large force was assembled against him at the fort, he and his warriors became alarmed, and a meeting of the Soldier’s Lodge was called. At this it was determined to enter into negotiations for peace, and so on Sunday, two half-breeds with a flag of truce, rode into camp in a buggy drawn by a mule they had stolen from that very spot a few days before. They bore a letter from Little Crow, asking for peace. This chief, though a great liar, was not naturally cruel, and had opposed from the outset the murder of peaceable settlers, and women and children. The traders he killed ruthlessly, as his worst foes. Besides, there was no real harmony between the upper and lower Indians, and had not been for along time. This breach had been widened by the unwillingness of the latter to make an equal distribution of the plunder taken the first day at the Lower Agency. Chief among the disaffected, though not for this reason, was Paul, a civilized Indian, and head deacon of Mr. Riggs church, a brave and eloquent man. From the first, he had told the Indians that they were rushing on destruction, for the result of their action would be the extinction of the tribe. He and his friends were strenuous for peace.

Little Crow, in his letter, stated that they had been fighting because they could not get their rights, but were now willing to enter into negotiations for peace. But Sibley replied that he would listen to no terms until the prisoners were restored. But Crow saw, if this were done, he would lose the last hold on the whites. Still, the upper Indians advised it should be done. Council after council was held, in which the debates grew stormy, and for a while the two parties threatened to come in collision. Some, even advised to kill Paul, the boldest advocate of the measure, but he openly defied them, saying that if they killed him they would have to kill three hundred more Indians at his back.

Nothing came of the negotiations, and the Indians remained at the Yellow Medicine, and Sibley at Fort Ridgely making preparations to move against them. More than a fortnight was consumed in getting ready, which occasioned great impatience and loud complaints throughout the country. He, however, was determined not to move till he was sure of success. In the mean time several letters were clandestinely received from the friendly Indians, promising their friendship, and quite a number of prisoners, through their agency, succeeded in escaping.

Defeats The Indians, Prisoners Rescued

At length, on the 18th of September, Sibley took up his line of march, and sweeping over the once fair, but now blackened and desolate country, arrived in four days within sight of the ruined and charred building of the Yellow Medicine Agency. The Indians had destroyed the bridges along the road, but these were easily rebuilt, with the exception of an important one near the Yellow Medicine Ravine. When the pioneers advanced to reconstruct this, the Indians fired upon them. A fight ensued in regular Indian fashion, which lasted for some time, but was finally ended by a gallant charge of Lieut. Colonel Marshall, at the head of the seventh regiment, who drove them like sheep before him. Had Sibley been furnished, as he ought to have been, with a large body of cavalry, he would have finished the war with a blow. As it was, this victory broke the spirit of the tribe. Little Crow, with two hundred men, fled into Dakotah territory and scattered. The remainder, with the Mission Indians, retained the captives, and immediately sent a flag of truce to Col. Sibley, requesting him to come and take them before Little Crow could attack them and carry off or kill the prisoners. The army at once took up its line of march, and the next day about noon, came in sight of the Indian camp, composed of about a hundred wigwams. An Indian on a pony, and carrying a bed-sheet tied on a pole as a flag of truce, approached, while a white cloth floated from the top of almost every hut. The column, marching slowly around them, encamped near the river. The painted warriors, fresh from their carnival of blood, at once came forward, smiling and offering to shake hands with every one, and expressing the most profound gratification at seeing their dear friends, the whites, once more. A demand was instantly made for the captives, when over two hundred sad, wan looking beings, some of the women and children half naked, were led out. Tears rained down their faces as with clasped hands they raised their eyes to their deliverers. The soldiers were jubilant, and unbounded joy reigned throughout the camp. Other captives, day after day, were brought in, and the tales they told of hope deferred, suffering and abuse, were heart-rending. Death had incessantly stared them in the face, and often a fate worse than death was offered them. Some had been treated kindly, and among them was the wife of Mr. Huggins, the missionary at Lac qui Parle. Wholly unconscious of danger, she was sitting in her house, surrounded with all the comforts of civilized life, when three Indians, each carrying a gun, entered. They sat down, and appeared to be much interested in watching the operations of a sewing machine, which a young lady was working. Soon after, Mr. Huggins came to the door from the field, where he had been at work. The Indians immediately went out, and the next moment Mrs. Hug-gins heard the report of two guns. She had barely time to look up, when the Indians rushed in, exclaiming, “Go out; go out; you shall live; but go out; take nothing with you.” She hastened out, and there lay her husband, a corpse on the ground. Providentially she fell into the hands of Walking Spirit, an old chief, and friend of her husband, in whose house she remained, treated with constant kindness by himself and family, until her release. Some of the escapes were most marvelous, and could not be credited were they not substantiated by the most unimpeachable testimony. Among these, none were more remarkable than that of a boy named Burton Eastlick, only ten years of age. Left alone with a little brother, only five years old, he started for Fort Ridgely, eighty miles. He did not know the way thither; he only knew it was somewhere down the river, and he set out to reach it. The spectacle of those two mere infants, on that far desolate prairie, linked hand in hand, and turning their little faces southward for protection, might well move the pity of the great Father of us all. With cunning beyond his years, the eldest took every precaution not to be seen by the Indians. When his little brother became foot-sore and weary, he would take him in his arms and carry him till he himself was tired out, and then they would rest together. Living on berries and such fruit as they could find, they traveled during the day, and when night came, would lie down in each other s arms, under the open sky. Thus the brave little fellow kept on, and encouraging his infant brother with all kinds of promises, actually made the eighty miles in safety, and reached the fort to tell his marvelous story. If all the incidents of this wonderful journey the shifts resorted to, and the innocent prattle by the way could be known and related in all their touching details, it would equal the strangest creation s of fiction.

In another case a woman succeeded in getting out of her house with her three children, undiscovered by the Indians. The youngest was an infant, and carrying this in her arms, with two little girls hanging on to her dress, she plunged into a thicket; she got off, and struck out into the prairie, not knowing whither she went. All day this sad group traveled on, uncertain whether each step was taking them nearer to, or farther from, safety. When night came, the trembling mother laid down under a bush, and pulling some grass and leaves for the two little girls, committed herself to Him who hears the young ravens when they cry. With the morning, she resumed her disconsolate journey, oppressed with the fear that she might be going farther and farther from home. Wild plums and berries kept them from starvation, and thus they traveled day after day, directing their steps at random, and looking in vain for some familiar object, or sign of human habitation. Between the miserable food she was compelled to eat, and her fatigue, she could not furnish her baby nourishment, and it gradually sickened and died. The anguish of her heart as she bore the little sufferer in her arms, and her utter desolation as she laid it at last dead on the prairie, can never be told. Gathering some leaves and grass, she covered it carefully from sight, and placing some sticks across the heap so that the wind should not uncover its delicate form, she left it with its God, and with the remaining two, hurried away. She wandered thus, lost on the prairie, till the summer verdure was gone, and the frosts of autumn robbed her of the berries and plums, and she had to dig roots to keep her self and little girls alive. For seven weeks she roamed about in this way, hoping each day would bring her on the track of some white man, before she was discovered and saved. In many cases, the women lost their reason, and wandered around, unfettered lunatics, in the thickets, until by accident they were found. Others still, strolled into the hands of the Indians, and were murdered or subjected to a still more cruel doom. Many a heart-rending tale will never be told, for the tongue that could have related it is still in death.

Women Of New Ulm Attack The Prisoners

Col. Sibley named his camp “Camp Release,” and as soon as the captives had been cared for, he built in it a huge log-pen for a jail. When it was finished, a force under Col. Crooks was dispatched by night, which quietly surrounded the Indian camp, and took all the men prisoners, except those known to be true friends, and locked them up, and the next day secured them with fetters. The camp itself, now consisting mostly of women and children, was removed to the Lower Agency, and finally to Fort Snelling. In the mean time, Lieutenant-Colonel Marshall, with two hundred men, was sent on an expedition into the Dakotah territory. As he was advancing in the direction of James River, he heard that a part of Little Crow’s band was encamped at Wild Goose Nest Lake. Approaching them stealthily by night, he succeeded in capturing the whole. On his return, it being now late in the season, it was determined to return; so October 28d, the camp was broken up, and with four hundred prisoners, loaded twelve or fifteen together, in each wagon, the column took up its line of march south ward, towards Mankato. As it passed through New Ulm, on Sabbath morning, the inhabitants, most of whom had returned, sallied forth with pitchforks, hoes, rakes, knives, guns, and brickbats, in fact with every missile they could lay their hands on, and fell with fierce imprecations on the wagons containing the prisoners, determined to save the government the trouble of hanging them. Even the women, with their aprons full of stones, danced in a perfect frenzy round the wagons, clamorous for a chance at the “red devils,” as they called them. One woman actually pounded an Indian brave on his head till he fell out of the wagon. The mob, however, was soon dispersed, and the column moved on and encamped about two miles from Mankato, at Camp Lincoln. In the mean time a military commission had set at the Lower Agency, to try the prisoners. The scene at the trial and execution was a strange mixture of the revolting, the sad and the ludicrous. The childish subterfuges and falsehoods of some of these braves, whose sagacity in the field was a match for the white man, were laughable, while the brutish in difference and stolid depravity of others; were painful to witness. The trial was hurried through, and three hundred and three were condemned to be hung, and eighteen to be imprisoned for life. The proceedings were sent to Washington for ratification. A rumor spreading that mercy was to be shown to the criminals, it aroused the deepest feelings in the west, and threats were even uttered to take them out of the hands of the authorities, and give them over to popular vengeance. A mob did attack the jail, but was dispersed by the decision of Col. Miller, then in command of the camp at that place. Mr. Riggs visited the prisoners constantly, and every kindness was shown them. A very few, however, seemed to be moved by it, receiving their fate with the accustomed indifference of the Indian. Some complained that they had been deceived by the promise of mercy if they surrendered them selves, and laid the blame of the whole difficulty on the whites, who by their injustice had forced them to seek redress by violence.

After several weeks delay the decision was received from Washington, ordering that only thirty-eight of the whole number should be executed. The 26th day of February was fixed for the execution. These were immediately separated from the rest, and their fate announced to them. They received it with total indifference smoking all the time, some even relighting their pipes, while the sentence was being read.

Their Behavior Mounting The Scaffold

The morning they were to be led out, they put on extra paint to decorate themselves for the occasion, and then commenced their death song. The melancholy chant, now sinking into a low wail, and again rising to a shrill, exultant cry, rang with strange power through their rude prison. At ten o clock they were brought forth, and marched in procession to the scaffold. They showed no signs of fear; on the contrary, they “went eagerly and cheerfully, even crowding and jostling each other, to be ahead, just like a lot of hungry boarders rushing to dinner in a hotel.” As they began to ascend the scaffold, they again raised their weird death song, and when they reached the top, broke out into unearthly shouts. A vast crowd had assembled, but all angry feelings were laid to rest by the painful spectacle, and a death-like silence reigned throughout. When all was ready, three slow, measured beats of the drum broke the stillness, and with a single blow, the rope was cut, and the whole were launched into eternity together.

The execution of this small number, seemed wholly inadequate to satisfy the demands of justice, for six hundred and forty-four whites had been massacred in cold blood, and ninety-three soldiers had fallen in the efforts to repel the outbreak. Perhaps the government thought this inequality in the number of sufferers, fairly represented the amount of actual guilt on both sides. To say that massacres must be avenged, in order to justify our slaughter of Indians, is a logic that will not stand before the great tribunal of heaven. The amount of injustice and wrong-doing that provoked the savage to the only means of redress left open to him, will be reviewed in the final adjustment there. This is but the beginning of troubles, if the nation persists in the policy it has pursued for the last thirty years. The Chippeways are nearly three times as strong as the Sioux, numbering some four thousand warriors in the United States, and about as many more in Canada, and they have been more than once on the point of an outbreak, growing out of the action at Washington. It becomes the people to inquire why it is that we are scarcely ever without an Indian war on our borders, while Canada has never been cursed with one. This single fact shows that there is a radical wrong in our system.