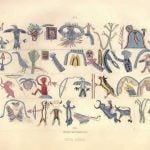

Plate 51

Wabeno: It has been stated that this institution among our Indians is a modification of the ceremonies of the Meda. It is stated by judicious persons among themselves to be of modern origin. They regard it as a degraded form of the mysteries of the Meda, which, according to Pottawatomie tradition (page 317), were introduced by the Manitoes to revive Manabozho out of his gloom, on account of the death of Chebiábos. It permits the introduction of a class of subjects, which are studiously excluded from the Meda. It is in the orgies of this society alone, that we hear the topic of love being introduced. Songs of love mingle in its mysteries, and are made subjects of mnemonic record. The mysteries of this institution are always conducted at night, and never by day. Many of the deceptions practiced in the exhibition of its arts, derive their effect from the presence of darkness. Tricks by fire are of this character. The sounds of its orgies are often heard at very late hours; and if the sound of the Indian drum be heard after midnight, it may generally be inferred with certainty to proceed from the circle of the Wabenoes. The term Wabeno itself is a derivative from Wabun, the morning light. Its orgies are protracted till morning dawn. Men of-the-Dawn, is a free translation of the term in its plural form.

In exhibiting the characters of the pictorial art as applied to the dances and songs of the Wabeno, it is essential to exhibit the character and tendency of the institution, as based on Indian manners and customs. There is so little truly known on the subject, that the investigation is not deemed out of place. Almost all the allusions of travelers on this topic are vague, and its ceremonies are spoken of as things to be gazed and wondered at. Writers seem often to have partaken of no small part of the spirit of mystery which actuated the breasts of the performers.

The season of revelry and dissipation among these tribes is that which follows the termination of the winter and spring hunts. It is at this time that the hunter’s hands are filled; and he quits the remote forests where he has exerted his energies in the chase to visit the frontiers, and exchange his skins and peltries and his sugar for goods and merchandise of American or European manufacture. Means are thus enjoyed which he cannot as well command at any other season. But, above all, this is the portion of the year when the hunting of animals must be discontinued. It is the season of reproduction. Skins and furs are now out of season, and, if bought, would command no price. Nature herself provides for this repose: the pelt is bad, and parts from the skin. By the 1st of June, throughout all the latitudes north of 42°, the forests are deserted, and the various bands of hunters are found to be assembled round the frontier forts and towns, or dispersed along the shores of the lakes and rivers in their vicinity. It is the natural carnival of the tribes. The young amuse themselves in sports, ball playing, and dances. The old take counsel on their affairs. The medas, the wabenoes, and jossakeeds, exert their skill. It is the season for feasts: all hearts are disposed to rejoice. As long as means last, the round of visits and feasting is kept up. By a people who are habitually prone to forget the past, and are unmindful of the future, the cares and hardships of the hunter’s life are no longer thought of. The warmth and mildness of the season is a powerful incentive to these periodical indulgences: dissipation is added to sloth, and riot to indulgence. So completely absorbing are these objects so fully do they harmonize with the feelings, wishes, theology, and philosophy of the Indian mind, that the hours of summer may be said to slip away unperceived, and the Indian is awakened from his imaginary trance at the opening of autumn, by the stern calls of want and hunger. He now sees that he must again rouse himself for the chase, or starve. He must prepare once more to plunge into the recesses of the forest, or submit to that penury and degradation which is the price of his continuance within the settlements. The tempests of autumn, which begin to whistle around his summer wigwam, are no surer tokens of the ice and snows which will block up his path, than the failure of all his means are, that it is only by renewed exertion, and a manly resort to his gun and trap, his arrow and his spear, that he can replace them. Such is the round of vicissitudes of Indian life. He labors during the fall and winter, that he may enjoy the spring and summer. He accumulates nothing but his experience; and this tells him that life is a round of severe trials, and he is soonest happy who is first relieved of it. He has no religion to inform him of the realities of a state of futurity; and the consequence is that he is early wearied of this round of severe vicissitudes, and is absolutely glad when the hour of death arrives.

The whole tendency of the Indian secret institutions is to acquire power, through belief in a multiplicity of spirits; to pry into futurity by this means, that he may provide against untoward events; to propitiate the class of benign spirits, that he may have success in war, in hunting, and in the medical art; or by acceptable sacrifices, incantations, and songs, to the class of malignant spirits, that his social intercourse and passions may have free scope. It is to the latter objects that the association of the wabeno is directed. Full examples of its songs and ceremonies, as recorded in the pictorial inscriptions, will be submitted, because, without such testimony, symbol upon symbol and song upon song, the actual scope and purport of it, and its important influence upon the Indian mind, could not be understood.

The following eighteen symbolic signs, constitute part No. 2 of Plate 51. It is to be remarked that the order of these figures is strictly observed, but in taking impressions from the wooden tablet on which they were originally cut, the plate is reversed. This does not affect the numbers, or the order of interpretation.

Figure 1 represents a necromancer’s or wabeno s hand, in a supplicating posture, holding a bone. Such an object is worn as a charm or amulet, in a belt around the body. He opens the rites he is about to perform with an address, of which the following is a translation:

I speak to the Great Spirit to save my life by this token, (the bone,) and to make it efficacious for my preservation and success. It is not I that have made it, but thou, Great Spirit, who hast made this world, and all things in it. Hear me, and show pity to my cry. He then sings

(Cabalistic chorus.} Na ha

Yaw ne

Na ha

Yaw ne

Ning o sau hau wa be no.

I am a friend of the wabeno.

Figure 2. Symbol of a tree which is supposed to emit supernatural sounds, some times like a great gun, and is thought to be the residence of a spirit.

(Cabalistic chorus.] Hi au ha

Ge he he

He he ge

Hi au ha

Hi au ge

We gau bo we aun.

I (the tree) sound for my life as I stand.

The drum and she-she-gwun are used while these chants are being sung as solos by the wabeno, the Indians, in the mean time, sitting. As soon as they are finished, they rise, and begin to dance.

Figure 3. A wabeno dog, running towards his master, who is in the act of vomiting blood. All sing

In dau ge

We but to

Ne au wee

In dau ge

We but to

Ne au wee. (Repeat and transpose.)

I shall run to him who is my body.

(Cabalistic chorus.) Hi au ha

Ge he he

He he ge

Hi au ha

Hi au ge.

Figure 4. A sick man throwing up blood.

In gau ge we na

In gau ge we na

Wa be no nis se o doan.

I struggle for life Wabeno kill it.

Figure 5. The Pipe. The idea represented is, that “bad medicine” has been applied to the pipe it is unsuspectingly smoked by one whom the owner wishes to injure. The smoke enters his lungs he withers up.

Me da wug

In goos au

Op-wau gun

In goos au

Way me gwun id.

Hi au ha, &c.

The meda I fear the pipe I fear that has feathers on.

Figure 6. A worm called Mb sa, that eats decaying wood, making a sounding noise.

Wa be no

Mo say

Wi au

In dau wau

Mo say

Wi au

Mo say

Wi au

Ne in dau wau.

Hi au ha, &c.

The Mosay’s skin I use The Mosay’s skin I use. Figure

Figure 7. A Wabeno Spirit, who is addressed for aid.

Aw wa nain

Pau ne bow id

Wa be no

Mon e do

Pau ne bow id

Au wa nain, &c.

Hi au ha, &c.

Who is that, standing there? A wabeno spirit, standing there!

Figure 8. An Indian hunter, gifted with the arts of the Wabeno, holding a bow and arrow. He is hungry he goes out to hunt he has four arrows. He finds a moose’s track, and observing where the animal has urinated, takes some of the urine and after mixing his medicines in it, puts some of it upon his arrow and fires into the track. The moose is seized with a strangury, and falling behind his companions in consequence, the Indian is able to overtake and kill him.

(Cabalistic chorus.} Way ha

Way ha

Yau hah

Way ha

Was sau way kum ig

A nuh ke yaun.

Way ha, &c.

I shoot far over the earth.

Figure 9. The sign symbolizing the Great Spirit, filling the sky with his presence.

A ne kwa

Ge bi aun

Ge zhick wun

Hi au ha, &c.

Where I sit, my head points to the center of the sky.

At this point of the ceremonies there is a pause. The singers and performers having completed certain evolutions around the Meda lodge, sit down. After a time, they arise, and resume the ceremonies, dancing, and moving about the lodge, in a certain order, while they sing, and shake their she-she-gwuns, or rattles.

Figure 10. The sky with clouds.

Ah no kwut

I a ha

Ah no kwut

Ge zhig o

Neen gee zhig o

Ah no kwut.

Hi au ha, &c.

The cloud that is in my sky the cloud that is in my sky.

Figure 11. A cloudy sky, with a fabulous animal, called the white tiger, with a long tail, who chases the clouds. He is sometimes represented with wings from the centre of his back. He now wishes to see above: i. e., to peep into futurity.

Ke zhig

O wee

Wa bun daun

O ho. (Repeat and transpose.)

Hi au ha, &c.

He wishes to look into the sky. Into the sky he wishes to look.

Figure 12. A wolf called Mohwha. He is depicted with horns to denote power. The idea called to mind by this figure is this, Meda-win, or mystic medicine, has been put on the head and tail of the animal, to induce him to hunt for the wabeno.

Neen gah gee

O sau go to

Ge ha

Mah bah

Moh wha, he he wau.

Hi au ha, &c.

I shall hunt the prey. This wolf of mine.

At this point of the ceremonies there is a pause, denoted by the two vertical bars of the symbolic inscription. They now arise, and the drum and dance is renewed.

Figure 13. The Kanieu, or War Eagle. This bird, the theory affirms, hovers near the fight, and eats the slain as soon as the battle is ended. His feathers indicate the highest honors, when worn by warriors.

Tah gee zhig ho (Tah is imperative; Ho calls to action.)

Tab gee zhig o

Pe nay see wug (Plural in wug.)

Tab gee zhig ho.

Hi au ha, &c.

They shall gather in the sky. The birds shall gather in the sky.

Figure 14. A bow and arrow. When the follower of these arts wishes to kill a particular animal, a grass or cloth image of it is made, and hung up in his wigwam. After repeating the following incantation, he shoots at the image. If he drives the arrow into it, it is deemed a sign that the animal will be killed next day, and the arrow is immediately drawn out and burnt.

Hi nab ka (declaration.)

Ne ah way

Hi nah ka

Ne ah way. (Repeat four or five times.)

See how I fire!

Figure 15. A master of the magical or Meda art sitting on the globe: with one hand he holds the sky the forked end of which, as delineated, represents a cloud symbolically. 1 He is drawing down knowledge from the sky for the benefit of the human race.

Na nau hau be

Na nau hau be

Gee zhig oom

A no o maun.

What do I see? What do I see? My sky that I am pointing to.

Figure 16. The sun representing the Great Spirit. He is symbolized as looking down upon the Indians, and is pleased to behold these ceremonies.

Tau neen a

Wau bum a un

Tau neen a

Wau bum a un

Kau nah wau bum e aun a

Kau nah wau bum e aun a.

Why do you look at me?

Figure 17. A bow and arrow, the latter directed downward. This is represented as an enchanted bow. There is a post in the centre of the lodge, and five pebbles lying in a row. The Wabeno affects to shoot through four of them, and the arrow sticks in the fifth, leaving them all strung upon its point.

Wa go nain

Ah wa nain

An au ka aun?

Os sin een e

Win o bun

Ah au ka aun? (Repeat three times.)

Why ! what is it I am firing at, on the ground ? It was pebbles I was firing at.

Figure 18. A young man, under the excitement of love, with feathers on his head, and a drum and drum-stick in his hands. He affects power to influence the object of his desires.

Nun dau wau kum

Ta way e gun

Nun dau wau kum

Ta way e gun

A zhau wau kum ig

In dun wa we turn

A zhau wau kum ig

In dun wa we turn.

Hi, au, ha, &c.

Hear my drum hear my drum, [though you be] on the other side of the earth, hear my drum.

Thus far there is very little to draw a line between the principles of the meda and wabeno. With the exception of Figure 18, the general objects of the signs and chants are the same. The sun is employed here, as there, as the symbol of the Great Spirit. The ideas that are entertained of this Spirit are to be drawn from the belief of the wabeno, that he will exert his power, through necromancy, in the vegetable kingdom (Figure 2), and among the classes of animals and birds (Figures 3, 6, 11, 12, 13), that he will endow inanimate objects with equal power (Figures 5, 14, 17), and, finally, that he will not favor the designs of men, when they are not directed to right and virtuous objects. This is clearly the province assigned by Indian belief for the antagonistical power of evil. If this be not demonology, we have no true conceptions of it. But we introduce some further illustrations.

Plate 52 depicts thirty mnemonic symbols of this institution, transcribed from the reverse of the tablet which yielded Plate 51.

Figure 1 depicts a preliminary chant. The figure represents a lodge prepared for a nocturnal dance, marked with seven crosses, to denote dead bodies, and crowned with a magic bone and feathers. It is fancied that this lodge has the power of loco motion, or crawling about. The owner, and inviter of the guests, sings solus.

Wa be no (Wabeno.)

Pe mo da (he creep, Ind. mood.)

Ne we ge warn (my lodge.)

Wa be no

Pe mo da

Ne we ge warn.

Hi, au, ha Nhuh e way Nhuh e way. Ha! ha! huh! huh! huh!

My lodge crawls by the Wabeno s power.

Figure 2. An Indian holding a snake in his hand. He has been taken, it is. under stood, underground by the power of medical magic, and is exhibited as a triumph of skill.

Ah nau

Muk kum mig

In doan

De naun

Nau muk

Kum mig.

Hi, au, ha, &c.

Under the ground I have taken him.

The inscription is here marked by a bar, indicating a pause. At this point the singing becomes general, and the dance begins, accompanied with the ordinary musical instruments.

Figure 3. An Indian in a sitting posture, crowned with feathers, and holding out a drum-stick.

Gi a neen (Gia, adverb also.)

Ne wa be no

Gi a neen

Ne wa be no.

Hi, a, ee, &c. (Repeat Cabalistic)

I too am a Wabeno I too am a Wabeno.

Figure 4. A spirit dancing on the half of the sky. The horns denote either a spirit, or a wabeno filled with a spirit.

Wa be no

Nau ne me au

Wa be no

Nau ne me au.

Hi, a, ee, &c. (Cabalistic.)

I make the Wabenos dance.

Figure 5. A magic bone decorated with feathers. This is a symbol indicative of the power of passing through the air, as if with wings.

Kee zhig

Ee me

In ge

Na osh

She au.

Hi! a! ee! &c. ( Cabalistic.}

The sky! the sky I sail upon!

Figure 6. A great serpent, called gitchy keenabic, always depicted, as in this instance, with horns. It is the symbol of life.

Mon e do

We aun A ko

Wa be no.

Nuk ka yaun.

Hi! a! &c. I am a wabeno spirit this is my work.

Figure 7. A hunter, with a bow and arrow. By appealing to his magical arts he fancies himself able to see animals at a distance, and to bring them into his path, so that he can kill them. In all this he is influenced by looking at his secret symbolical signs or markings.

Ne zhow

We nuk

Ka yawn

Ne zhow

We nuk Ka yawn.

Hi! a! &c. (Cabalistic.)

I work with two bodies.

Figure 8. A black owl.

(Rara avis.)

Ko ko ko

Au Ko ko ko

Au

Muk ko da

Ko ko ko

Au.

Hi! a! haa! &c. (Cabalistic.)

The owl the owl the great black owl.

Figure 9. A wolf standing on the sky. A gift is sought. This is the symbol of vigilance.

In dan

Na wau

In dau

Nun do

Na wau.

Hi! e! ha! &c.

Let me hunt for it.

Figure 10. Flames.

Wau nau ko

Na! ha! ha! (Cabalistic.)

Wau nau ho

Na! ha! ha!

Burning flames Burning flames.

Figure 11. This figure represents a foetus half-grown in the womb. The idea of its age is symbolized by its having but one wing. The singer here uses a mode of phraseology by which he conceals, at the same time that he partly reveals, a fact in his private history or attachments.

Ne chau nis

Ne chau nis

Ke zhow way

Ne min.

Hi! a! &c.

My little child my little child, I show you pity.

Figure 12. A tree, supposed to be animated by a demon.

Ki! au! ge!

We gau bo

We aun

Ki au ge, we gau bo, we aun.

Hi! a! &c.

I turn round in standing.

Figure 13. A female. She is depicted as one who has rejected the addresses of many. A rejected lover procures mystic medicine, and applies it to her breasts and the soles of her feet. This causes her to sleep, during which he makes captive of her, and carries her off to the woods.

Wa be no wau (Wabeno-power.)

Ne augh we na (Occult.)

Nyah eh wa, &c. (Triumphant chorus.)

A pause in the ceremonies is denoted by bars between figures 13 and 14.

Figure 14. A Wabeno spirit of the air. He is depicted with wings, and a tail like a bird, to denote his power in the air, and on the earth.

Wa be no

Ne bow

We tab

Wa be no

Ne bow

We tab.

Wabeno, let us stand.

Figure 15. An anomalous symbol of the moon, representing a great wabeno spirit, whose power is indicated by his horns, and rays depending from his chin like a beard. The symbol is obscure.

In di aun

O zbe toan

Neen ah

Ne peek wun au.

I have made it with my back.

Figure 16. A Wabeno bone ornamented similar to figures 1 and 5.

In ge

We nau wau

In ge

We nau wau.

I have made him struggle for life.

Figure 17. A tree with human legs and feet. A symbol of the power of the Wabeno in the vegetable kingdom.

Wa bun

Ne ge kee

We gau yaun.

I dance till daylight.

Figure 18. A magic bone. By this sign the performer boasts of supernatural power.

Ke we

Gau yaun

Ke we

Gau yaun.

Dance around, ye!

Figure 19. A drum-stick. The symbol of a co-laborer in the art.

Gi a neen

In gwis say.

And I too, my son.

Figure 20. A Wabeno with one horn, holding up a drum-stick. This figure denotes a newly initiated member.

We au be no wid

Nin go sau.

He that is a Wabeno, I fear.

Figure 21. A headless man standing on the top of the earth. A prime symbol of miraculous power and boasting.

Ke ow

We naun

Ke ow

We naun.

Your body I make go, (alluding to figure No. 1.)

Figure 22. A tree reaching up to the arc of the sky. He symbolizes the great power of the tree to whose magic power he trusts.

Neem bay

Shau ko naun

Ne met tig oam.

I paint my tree to the sky.

Figure 23. A human figure, with horns, holding a club. It is the figure of a Wabeno.

Hwee o (A cabalistic expression, supposed to express a wish.)

Gwis say

Hwee o

Gwis say. (Four repeats and chorus.)

I wish a son.

Figure 24. The falco furcatus or swallow-tailed hawk, called Shau-shau-won-e-bee-see, a bird that preys on reptiles. It is an emblem of power in war.

Wa be no

Ne gee zig oom. (Four repeats and chorus.)

My Wabeno sky.

The next figure of vertical lines denotes a pause. The dancers rest and then resume the dance.

Figure 25. A master of the Wabeno society, depicted with one horn reversed, and a single arm. The idea is, that with but one arm his power is great. His heart is shown to denote the influence of the Meda on it.

Git shee

Wa be no

Ne ow

Hwee. (Four repeats and chorus.)

My body is a great Wabeno.

Figure 26. A nondescript bird of ill omen.

Nin gwis say to kun

Pe mis say to kun.

My son s bone The walking bone,

Figure 27. A human body with the head and wings of a bird.

Ti um bau she wug

Ne kdun. (Repeat and chorus.)

They will fly up, my friend.

Figure 28. Mississay a turkey. A symbol of boasted power in the operator.

Mississay in dow au

Mississay in dow au.

The turkey I make use of.

Figure 29. A wolf. A symbol of assumed power to search.

Muh way wau

Hi au i aun.

I have a wolf, a wolf’s skin.

Figure 30. A flying lizard, or dragon snake. He calls in question the power assumed.

Kau we au Mon e do

Kau we au Mon e do

Wa be no Mon e do.

There is no spirit! There is no spirit! Wabeno spirit.

Figure 31. A Wabeno personified with the power of flying.

Wa hau bun o

Git shee Wa hau bun o

Git shee Wa bun o, ho!

Ge ozhe tone.

Great Wabeno! Great Wabeno! I make the Wabeno.

Here is another pause or division of the ceremonies, and songs. Figure

Figure 32. A pipe of ceremony. This is the emblem of peace. The operator smokes it to propitiate success.

Au neen meetay wau

Mo ne do wid

Wa bun e dun.

What, meda, my spirit brother, do you see?

Figures 33, 34. A symbol of the moon, with rays, &c. Represents a man and a snake.

Noan dau tib bik

Koot che hau no tau.

In the night I come to harm you.

Figure 35. A Wabeno. This is, apparently, a symbol of the sun.

Wa bun oong

Un i tau tub be aun.

I am sitting in the east.

Figure 36. A dragon-winged serpent, or Gitchee Kanaibik. Denotes great power over life.

Ne ow way; ne kaun

In ge we now waun.

With my body, brother, I shall knock you down.

Figure 37. A wolf depicted with a charmed heart, to denote the magic power of the Meda.

Ningo tohee

Muh whay

Ow wau.

Run, wolf your body’s mine.

Figure 38. A magic bone, the boasted symbol of necromantic skill. The words accompanying this figure were not given.

Citations:

- This drawing is found graphically to depict the leading idea embraced in Isaiah xl. 22. See Plate 51, No. 15. The same verse gives the leading thought of a curtained sky, represented in Figures 10 and 11 of the same plate.[

]