The treaty of peace concluded between Massasoit and the English at Plymouth, soon after the landing of the latter, was maintained faithfully until after the death of that sachem. He was succeeded by his son, whom the English had named Alexander. Although this chief displayed on all occasions a decided friendship for his white neighbors, his death was either caused entirely, or hastened, by their suspicious violence. Suspecting that Alexander was plotting with the Narragansetts to rise against the English, the council of Plymouth resolved to bring him before them to answer for his conduct. The following account of the capture and death of the chief is taken from the narrative of William Hubbard, a contemporary writer:

“The person to whom that service was committed, was a prudent and resolute gentleman, the present governor of the said colony, (Winslow,) who was neither afraid of danger, nor yet willing to delay in a matter of that moment; he, forthwith, taking eight or ten stout men with him, well armed, intended to have gone to the said Alexander’s dwelling, distant at least forty miles from the governor’s house, but by a good providence, he found him whom he went to seek at a hunting house, within six miles of the English towns, where the said Alexander, with about eighty men, were newly come in from hunting, and had left their guns without doors, which Major Winslow, with his small company, wisely seized, and conveyed away, and then went into the wigwam, and demanded Alexander to go along with him before the governor, at which message he was much appalled, but being told by the undaunted messenger, that if he stirred or re-fused to go, he was a dead man; he was, by one of his chief counselors, in whose advice he most confided, persuaded to go along to the governor’s house; but such was the pride and height of his spirit, that the very surprisal of him, so raised his choler and indignation, that it put him into a fever, which, not-with-standing all possible means that could be used, seemed mortal; whereupon, entreating those that held him prisoner, that he might have liberty to return home, promising to return again if he recovered, and to send his son as hostage till he could so do; on that consideration he was fairly dismissed, but died before he got half way home.”

Surely, this act was a violation of all international right. Alexander’s people had kept unbroken faith with the English ever since 1620. Yet, their prince was surprised and deprived of liberty, without the slightest proof of guilt, which, had they even possessed, they would not have had the right to make him a captive. This was one among the many just causes of the terrible war which Alexander’s brother was about to begin.

The younger brother of the unfortunate chief succeeded him as sachem of the Wampanoags. He had been named Philip by the English at the same time the name of Alexander was given to his brother; his Indian name was Metacomet. He was already known to possess an active and haughty spirit. Doubtless, the designs of Philip were formed at this time; but until they were sufficiently matured, he kept them well covered. He came to Plymouth, in 1662, and renewed the treaty with the English, his people had so long observed. An apparent good feeling existed between the parties for several years after this. During this period, Philip entered into war against the Mohawks, whom he finally defeated in 1669.

The first rupture between the Wampanoag chief and the colonists occurred in April, 1671. The Plymouth government accused him of meditating hostilities, and arming and training his warriors. He, in return, complained of encroachments upon his planting grounds. A conference was held at Taunton, at which Philip admitted the truth of the charges against him, promised amendment, and signed a new treaty. It was afterwards made clear, that this submission was but to gain time. With the same object, he visited Boston, in August, 1671, and succeeded in lulling the suspicions of the Massachusetts government. Another conference followed, and the sachem made still greater promises to the governments of Plymouth and Massachusetts. This purpose was fully answered, and nothing occurred for three years to rouse the suspicions of the whites. During all this time, Philip was most active in completing the vast designs which he had formed. His first object was, the union of all the New England tribes; and to affect this, he used all the arts of persuasion, of which he was a master. His success proves his ability. From the St. Croix to the Housatonic, the Indian tribes were formed into a vast confederacy, of which Philip was acknowledged as the head. The Wampanoags and the Narragansetts were the most powerful of these confederates.

The immediate occasion of Philip’s taking up arms was this. An Indian, named John Sausaman, who had been educated at Cambridge, and employed as a schoolmaster among the Christianized Indians, and had subsequently joined Philip, and acted as his confidential secretary, after becoming acquainted with his plans, deserted Kim, and turned spy and informer. In January, 1675, the body of Sausaman was found thrust under the ice in Assawomset Pond, and from subsequent developments, it was ascertained that he had been murdered, and by Philip’s orders. Three Indians were convicted of the murder, and executed at Plymouth; and Philip, suspecting that an attempt would be made to capture him for trial, resolved to anticipate his enemy’s projects, and begin the war at once.

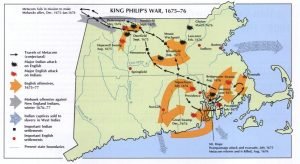

The Wampanoags sent their wives and children to the Narragansetts for security, and began to threaten the inhabitants of Swanzey. Growing bolder, they killed the cattle, and rifled the houses of the English, one of whom fired upon and wounded an Indian. This was the trump that roused both parties to action. Several of the inhabitants of Swanzey were murdered on the 24th of June, 1675. The Plymouth government sent information of the state of things about Mount Hope to the government of Massachusetts, and desired their speedy assistance. On the 28th, a foot company, under Captain Daniel Henchman, and a troop, under Captain Thomas Prentice, marching from Boston, joined the Plymouth force, under Captain Cudworth, at Swanzey, and marched into Philip’s country. A skirmish with the Indians followed, in which the English had one man killed and one wounded, but succeeded in driving their enemies to their swamp, with the loss of five men. At the same time, the Indians attacked Taunton, Namasket, and Dartmouth, burning a considerable number of houses, and killing many of the inhabitants.

On the 15th of July, Captain Hutchinson led a large force into the Narragansett country, and concluded a treaty with that tribe. This was to prevent them from joining the forces under Philip. At the same time, Captain Cudworth dispatched Captain Fuller and Lieutenant Church, with fifty men, to Pocasset, where Philip commanded, either to conclude a peace, if the enemy wished it, or to fight them, if necessary. This force was divided into two parties after reaching Pocasset, Captain Fuller leading one towards the sea shore, and Church marching further into the neck. Fuller found the Indians too strong for him, and after some skirmishing, he fled to the sea shore, and with his men, was taken off by a sloop. Church, with only fifteen men, found the Indians in great force near the peas-field; and he, too, was forced to retreat to the sea shore, where, however, he valorously defended himself against the great numbers of the Indians, until all the ammunition of his little band was spent; and even then, the Indians were forced to let the sloop take them off in safety. In this skirmish, the colonists killed fifteen of the Indians, and did not lose a man.

After obtaining reinforcement from Rhode Island, Captain Church boldly returned to Pocasset. Another skirmish followed, in which the Indians lost fourteen or fifteen men, and Philip was then forced to retreat to a great swamp. Not being able to reach the enemy in this strong hold, Church held them at bay until the arrival of the main body of the Plymouth troops, and then the whole pushed further into the swamp. As the contemporary writer, Hubbard, quaintly remarks: “It is ill fighting with a wild beast in his own den;” and so the Plymouth men found it. They, therefore, resolved to starve the enemy into submission. Philip knew his doom if he should become a prisoner to the English, and was determined never to fall alive into their hands. Selecting about two hundred of his best warriors, he contrived to cross an arm of the sea near the swamp, and thus escaped into the country of the Nipmucks. In the same manner, all but one hundred of the women and children, who submitted to the English, succeeded in getting away. Upon discovering this, the English set off in pursuit, aided by the Mohican Indians. About thirty of Philip’s men were cut off from the rear and slain; the rest escaped unharmed.

The Nipmucks had already commenced hostilities by killing five persons at Mendham. Without being aware of this, Captain Hutchinson, with twenty horse, marched into their country to reclaim the fugitives. He fell into an ambuscade at Brookfield, on the 2d of August, and lost sixteen men. An attack was then made upon that town; but the arrival of Major Willard, with forty-eight dragoons, saved it from destruction. Philip joined the Nipmucks on the next day. At this time, the Indians on the Connecticut River commenced hostilities. Captains Lothrop and Beers, with a small force, drove the Hadley Indians from their dwellings, and pursued them to Sugarloaf Hill, ten miles distant, where a skirmish took place, in which nine or ten of the English were slain, and about twenty-six of the Indians; the remainder escaped, and soon joined Philip.

Deerfield, Hatfield, and other places, felt the force of the Indian’s vengeance. An attack upon Hadley was repulsed, chiefly through the exertions of Goffe, one of the judges of Charles I, who lay concealed in that town. Several of the inhabitants of Northfield were killed; and the next day, Captain Beers, with thirty-six men, marching to the assistance of that place, was way-laid, and after a desperate battle, the captain and twenty men were slain; the others escaped to Hadley. Northfield was soon after destroyed by the Indians.

Captain Lothrop, with about eighty men, proceeding from Deerfield to Hadley, was waylaid near Sugarloaf Hill, by about seven hundred Indians, and after a hard fought battle, nearly the whole party was destroyed. The report of the guns being heard at Deerfield, Captain Mosely hastened forward to the relief of Lothrop. He arrived in time to renew the fight, and being joined by Major Treat, with a force of English and Mohicans, he compelled the foe to seek safety in a distant forest. As the Indians were emboldened by the destruction of Lothrop’s party, and the English forces were much diminished, Mosely thought it best to abandon Deerfield, and employ his strength in defending the three next towns on the Connecticut River.

In October, the Indians of Springfield, so long friends to the whites, formed a plan to burn that village, and received into their fort about three hundred of Philip’s warriors. A friendly Indian gave the inhabitants warning of their danger; but they were too credulous, and suffered themselves to be deluded until the time for action was at hand. But for the timely arrival of Major Treat, with a strong body of troops, the whole place would have been destroyed. As it was, thirty-two houses met the fate intended for all. On the 19th of October, Hadley was attacked by seven hundred Indians; but the valiant conduct of the troops stationed at that place, forced them to retire. After this repulse, the Indians all retired to the rendezvous at Narragansett. The approach of winter seemed to put a check to their enterprises. In all the operations of the war thus far, Philip was the ruling spirit among his countrymen. His activity, bravery, and cunning had been displayed on all occasions; and there remained no doubt of his being the most formidable chief the English ever had to encounter.

At a meeting of the commissioners of the United Colonies was held on the 9th of September. It was concluded that the war was just, and that it should be prosecuted to the utmost of their power. It was resolved to raise a thousand men with all expedition, and Josiah Winslow, the governor of Plymouth, was appointed commander in chief. The Narragansetts were considered as the accessories of Philip in his outrages, or, as many will say at the present time, his allies in the war; and hostilities were to be directed against them.

The forces of the three colonies assembled at Petaquamscut, on the 18th of December, and marched through a deep snow towards the enemy. The Narragansetts had retired to a small piece of dry land, in a great swamp, seven miles from Newport. Here they collected stores, and built the strongest fort they ever had in this country. A circle of palisades was surrounded by a fence of trees, a rod in thickness. The entrance was on a long tree over the water, that only one person could pass at a time. This was guarded in such a manner, that every attempt to enter would have been fatal. By the help of Peter, an Indian prisoner, but now a necessary guide, one vulnerable spot was discovered; at one corner the fort was not raised more than four or five feet in height, opposite to this spot a block house was erected, so that a torrent of balls might be poured into the gap.

General Winslow, with fifteen hundred men from Massachusetts, and three hundred from Connecticut, with one hundred and sixty Indians, being arrived near the place about one o’clock, having traveled eighteen miles without refreshment or rest, discovered a party of the enemy, upon whom they instantly poured a shower of balls; the Indians returned the fire and fled into the fort. The English pursued, and without waiting to reconnoiter or even to form, rushed into the fort after them; but so terrible was the fire from the enemy, they were obliged to retire. The whole army then made a united onset; hardly were they able to maintain their ground; some of their bravest captains fell. In this awful crisis, while the scale of victory hung doubtful, some of the Connecticut men, who were in the rear on the opposite side, where was a narrow place destitute of palisades, leaped over the fence of trees, and fell on the rear of the enemy. This decided the contest. They were soon totally routed.

As they fled, their wigwams were set on fire. Instantly six hundred of their dwellings were in a blaze. Awful was the moment to the poor savages. Not only were they flying from their last hope of safety, and from their burning houses, but their corn, their provisions, and even many of their aged parents and helpless children, were fuel for the terrible conflagration. They could behold the fire, they could hear the last cries of their expiring families; but could afford them no relief. Seven hundred of their warriors they had left dead on the field of battle; three hundred more afterwards died of their wounds. They had been driven from their country, and from their pleasant fire sides: now, their last hopes were torn from them; their cup of sufferings was full.

Sad was the day of victory to the English. Six brave captains fell before their eyes; eighty men were killed or fatally wounded; one hundred and fifty were wounded who recovered. Twenty fell in the fort, ten or twelve died the same day, on their march back to their camp, which they reached about midnight; it was cold and stormy, and the snow deep; several died the next morning, so that this day, December 20th, they buried thirty-four in one grave. By the 22d, forty were dead, and by the end of January, twenty more. Of the three hundred from Connecticut, eighty were killed or wounded. Of their five captains, three were killed, and one so wounded, that he never recovered. In the fort they had taken a large number of prisoners, about three hundred warriors, and as many women and children. It was supposed that four thousand natives were in the fort when the assault was made.

The natives never recovered the loss of this day. The destruction of their provisions in the fort was the occasion of great distresses in the course of the winter. But a thaw, in January, gave them some relief, when a party fell on Mendon, and laid it in ashes. In February, they received some recruits from Canada; when they burned Lancaster, and took forty captives, among whom was Mrs. Rowlandson, the minister’s wife, he being on a journey to Boston to obtain soldiers for their defense. Marlborough, Sudbury, and Chelmsford soon felt the terror of their arms. February 21st, they penetrated as far as Medfield, burned half the town, and killed about twenty of the inhabitants; in four days they were in Weymouth on the sea shore, and in the same month, they dared to enter Plymouth, and destroy two families. Had they been so disposed fifty years before, instead of two families, they might easily have destroyed the whole colony. In March, they were in Warwick, and burned the town. They were pursued by Captain Pierce, with fifty English and twenty Indian soldiers, but he was overpowered by numbers, himself and forty-nine of the English, with eight of the Indians, being slain, after they had killed one hundred and forty of the enemy. The same day, Marlborough was in flames, and several people were killed at Springfield.

On the 18th of May, a party of one hundred soldiers marched to Deerfield, and surprised a large party of Indians stationed there. The red men could make but little resistance, and about three hundred men, women, and children were either killed by the English, or drowned in the Connecticut River. Soon after, a party of the Indians rallied, and attacked the whites with great fury. Captain Turner and thirty-eight men were killed. The remainder of the party was brought off by Captain Holyoke.

In revenge for the loss sustained by this surprise at Deerfield, six or seven hundred Indians appeared before Hatfield on the 30th of May, and burning several houses and barns, proceeded to attack the houses within the palisades. The approach of a body of young men from Hadley, compelled them to desist; and they retired with the loss of twenty-five men. The Narragansetts were nearly all driven out of their country by the numerous volunteer companies of the English.

Early in June, Major John Talcot, with two hundred and fifty soldiers, and two hundred Mohicans and Pequot Indians marched from Norwich into the Wabaquasset country. But he found it entirely deserted. On the 12th of June, Hadley was again attacked by about seven hundred Indians; but Talcot appeared, and drove off the enemy. On the 3d of July, the same commander came up with the main body of the Indians, near a large cedar swamp, and attacked them so suddenly, that a great number were killed upon the spot. The remainder, taking refuge in the swamp, were surrounded by the English, and a still greater number were killed or captured. By the 5th of July, when Talcot retired to Connecticut, he had destroyed or taken above three hundred Indians.

Disheartened by such disastrous defeats, the Indians began to come to the English in small parties and surrender themselves. Philip fled to the Maquas; but they proving hostile, he was compelled to return to the vicinity of Mount Hope. But his spirit was not broken yet. With all the force he could collect, he fell upon Taunton on the 11th of July. The inhabitants had received timely warning, and were prepared. Philip was compelled to retire, after burning a few houses. During the month of July, the troops under Captain Mosely and Brattle, and the Plymouth forces, under Major Bradford, killed and captured one hundred and fifty Indians without losing a man.

About the same time, the valiant Captain Church, with a small party of eighteen English and twenty-two Indians, fought four battles in one week, killing and capturing seventy-nine of the Indians, without losing a man. On the 25th of July, thirty-six Englishmen and ninety Christian Indians, from Dedham and Medfield, took fifty prisoners, without losing one of their own number. Two days after, Sagamore John, with one hundred and eighty Nipmucks, submitted to the English. Upon the 1st of August, Captain Church captured twenty-three Indians; and on arriving at Philip’s headquarters, killed and captured many more.

The close of the career of the great chief who had inflicted so much upon the English, as the invaders of his country, is worthy of particular notice. Quanonchet, the intimate friend of Philip, venturing near the enemy with a few followers, was pursued and taken. When offered life, if he would deliver Philip into the hands of the English, he nobly refused. They condemned him to die by the hands of three young Indian chiefs. The hero replied, that he “liked it well; for he should die before his heart was soft, or he had spoken anything unworthy of himself.” But, although the day of adversity was upon Philip, he retained his wife and child as a consolation until after he took refuge at Mount Hope. While there, his quarters were surprised, and the greater part of his people, including his wife and child, killed and captured. The almost deserted chief fled, leaving his dearest ones to the mercy of those who did not feel that virtue. Though defeated, and hunted like a wild beast, Philip was not conquered.

The sorcerers attempted to console the chief with the assurance that he should never fall by the hand of an Englishman. Gathering his little band around him, he took refuge in an almost inaccessible swamp, there resolved to make a last stand. As an instance of determined spirit and hatred of the English, it is related, that an Indian proposed to make peace with the enemy. Philip instantly laid him dead at his feet. A friend or relation of this man, exasperated at the deed, fled to the English and offered to conduct them to the place of his retreat. Captain Church, awake to the importance of the capture, marched with this welcome guide, upon his certain expedition. Philip had been dreaming the night before, that he had fallen into the hands of the English, and was telling his dream to his men, when Church and his followers rushed in upon them. The battle was short, but desperate. Philip fought till he saw almost all his men fall in his defense, and then turned and fled. He was pursued by an Englishman and an Indian. As if the oracle was to be fulfilled, the musket of the former would not go off; the latter fired, and shot him through the heart. Thus fell one whose acts proved him to possess the abilities of a great prince. The colonists rejoiced that they were delivered from a terrible enemy, and were not then capable of forming a true judgment of his character. It is evident, Philip did all that was possible for an untutored savage chief to perform, with the object of delivering his country from those he looked upon as invaders. He possessed a mind capable of forming great plans, unwearyingly activity and perseverance, the power of molding men to his purposes, and with much of the cruelty implanted by savage trainings, had some of the finest of human feelings.

Although peace was not established securely until sometime after Philip’s death, the war may be said to have virtually terminated by it. Annawon, a Wampanoag chief, with a few followers, escaped from the swamp, and for awhile threatened Swanzey. This chief resolved never to be taken alive by the English. Captain Church pursued him with a considerable body of colonists and treacherous Indians, and overtook him as he was preparing a meal at the foot of a precipice. All resistance was useless, and Annawon was forced, despite his resolution, to yield himself and followers prisoners. He was a true Indian warrior. As the victorious Church passed the night upon the spot where Annawon was captured, the chief recounted the injuries he had done the English, and the valiant deeds he had performed in many wars, with a feeling of pride no fear of death could tame. He was taken to Plymouth, and in accordance with the brutal policy of the colonists, was beheaded.

The war had lasted fourteen months. The New England colonists had lost six hundred of their number, killed; and had thirteen towns totally, and eleven, partially, destroyed. A heavy debt had also been incurred to defray the expenses of the contest; and the labors of the Christian missionaries among the Indians entirely interrupted. Two or three powerful tribes of the native owners of the soil had been annihilated, and the remainder, lacking the spirit of Philip, were reduced to submission.