The kingdoms of New Spain, as Central America and the adjoining country were first called, presented a far different aspect, when first discovered by Europeans, from that of the vast and inhospitable wilderness at the North and East. Instead of an unbroken forest, thinly inhabited by roving savages, here were seen large and well-built cities, a people of gentler mood and more refined manners, and an advancement in the useful arts which removed the inhabitants as far from their rude neighbors, in the scale of civilization, as they themselves were excelled by the nations of Europe.

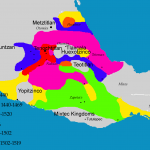

When first discovered and explored by Europeans, Mexico was a kingdom of great extent and power. Montezuma, chronicled as the eleventh, in regular succession, of the Aztec monarchs, held supreme authority. His dominions extended from near the isthmus of Darien, to the undefined country of the Ottomies and Chichimecas, rude nations living in a barbarous state among the mountains of the North. His name signified ” the surly (or grave) Prince,” a title justified by the solemn and ceremonious homage, which he constantly exacted.

“When the Spaniards first appeared on the coast, the natural terror excited by such unheard-of conquerors was infinitely heightened by divers portents and omens, which the magicians and necromancers of the king construed as warnings of great and disastrous revolutions. This occasioned that strange, weak, and vacillating policy, which, as we shall hereafter see, he adopted towards Cortez. Comets, conflagrations, overflows, monsters, dreams, and visions, were constantly brought to the notice of the royal council, and inferences were drawn there from as to the wisest course to be pursued.

The national character, religion and customs of the Mexicans presented stranger anomalies than have ever been witnessed in any nation on the earth. They entertained abstract ideas of right and wrong, with systems of ethics and social proprieties, which, for truth and purity, com pare favorably with the most enlightened doctrines of civilized nations, while, at the same time, the custom of human sacrifice was carried to a scarcely credible extent, and accompanied by circumstances of cruelty, filthiness, and cannibalism, more loathsome than ever elsewhere disgraced the most barbarous of nations.

A vast amount of labor and research has been expended in efforts to arrive at some satisfactory conclusion as to the causes, which led to the Mexican superiority in the arts of civilization over the other inhabitants of the New World. Analogies, so strong as to leave little doubt upon the mind that they must be more than coincidences, were found, on the first discovery of the country, between the traditions, religious exercises, sculpture, and language of the inhabitants of Central America, and those of various nations in the Old World. Notwithstanding this, the great distinctive difference in the bodily conformation of all natives of the Western Continent, from the people of the East, proves sufficiently that, previous to the Spanish discoveries, the time elapsed since any direct communication could have existed between the two, must have been very great. The obvious antiquity of the architectural remains carries us back to a most remote era: some maintain that portions of these must have been standing for as many centuries as the great pyramids of Egypt, while others refer them to a much later origin. The pernicious habit of first adopting a theory, and then searching for such facts only as tend to support it, was never more forcibly exemplified than in the variant hypotheses as to the origin of Mexican civilization.

The valley and country of Anahuac, or Mexico, was successively peopled, according to tradition and the evidence of ancient hieroglyphics, by the Toltecs, the Chichimecas, and the Nahuatlacas, of which last-mentioned people, the Aztecs, who finally obtained the ascendancy, formed the principal tribe. These immigrations were from some indeterminate region at the north, and appear to have been the result of a gradual progression southward, as traces of the peculiar architectural structures of the Mexican nations are to be found stretching throughout the country between the Rocky Mountains and the sea, as far north as the Gila and Colorado.

The periods of these several arrivals in Anahuac are set down as follows. That of the Toltecs, about the middle of the seventh century, and of the rude Chichimecas, the year 1070. The Nahuatlacas commenced their migrations about 1170, and the Aztecs, separating themselves from the rest of the nation, founded the ancient city of Mexico in the year 1325.

The tale of cruelties, oppressions, and wholesale destruction attendant upon the Spanish invasion and conquest, is a long one, and can be here but briefly epitomized; but enough will be given to leave, as far as practicable, a just impression of the real condition of these primitive nations, and the more marked outlines of their history.

In the early part of the sixteenth century, the eastern shore of Mexico and Central America had been explored by Spanish navigators; and Vasco Nugnez de Balboa, led by the ordinary attraction tales of a country rich in gold and silver had, in September, 1513, crossed the isthmus to the great and unknown ocean of the West. The condition and character of the natives was but little noticed by these early explorers, and no motives of policy or humanity restrained them from treating those they met as caprice or fanaticism might dictate. Balboa is indeed spoken of as inclined to more humane courses in his intercourse with the natives than many of his contemporaries, but even he showed himself by no means scrupulous in the means by which he forced his way through the country, and levied contributions upon the native chiefs.

The mind of the Spanish nation was at last aroused and inflamed by accounts of the wealth and power of the, great country open to adventure in New Spain, and plans were laid to undertake some more notable possession in those regions than had yet resulted from the unsuccessful and petty attempts at colonization upon the coast.

Diego Valasquez, governor of Cuba, as lieutenant to Diego Colon, son and successor of the great admiral, sent an expedition, under command of Juan de Grijalva, to Yucatan and the adjoining coast, in April of the year 1518. After revenging former injuries received from the natives of Yucatan, the party sailed westward, and entered the river of Tobasco, where some intercourse and petty traffic was carried on with the Indians. The natives were filled with wonder at the ” make of the ships, and difference of the men and habits,” on their first appearance, and ” stood without motion, as deprived of the use of their hands by the astonishment under which their eyes had brought them.”

The usual propositions were made by the Spanish commander, of submission to the great and mighty Prince of the East, whose subject he professed to be; but ” they heard his proposition with the marks of a disagreeable attention,” and, not unnaturally, made answer that the proposal to form a peace which should entail servitude upon them was strange indeed, adding that it would be well to inquire whether their present king was a ruler whom they loved before proposing a new one.

Still pursuing a westerly course along the coast, Grijalva gained the first intelligence received by the Spaniards of the Emperor Montezuma. At a small island were found the first bloody tokens of the barbarous religious rites of the natives. In a “house of lime and stone” were “several idols of a horrible figure, and a more horrible worship paid to them; for, near the steps where they were placed, were the carcasses of six or seven men, newly sacrificed, cut to pieces, and their entrails laid open.”

Reaching a low sandy isle, still farther to the westward, on the day of St. John the Baptist, the Spaniards named the place San Juan, and from their coupling with this title a word caught from an Indian seen there, resulted the name of San Juan de Ulloa, bestowed upon the site of the present great fortress. No settlement was attempted, and Grijalva returned to Cuba, carrying with him many samples of native ingenuity, and of the wealth of the country, in the shape of rude figures of lizards, birds, and other trifles, wrought in gold imperfectly refined.

Seizure and Imprisonment of Montezuma

“And sounds that mingled laugh, and shout, and scream,

To freeze the blood in one discordant jar,

Rung to the pealing thunderbolts of war.”

Campbell.

Cortez was not yet satisfied; he felt his situation to be precarious, and that his object would not be fully accomplished until he had acquired complete mastery over the inhabitants of the imperial city. While he was on his march to Mexico, Juan de Escalente, commander of the garrison left at Vera Cruz, had, with six other Spaniards, perished in a broil with the natives. One soldier was taken prisoner, but dying of his wounds, his captors carried his head to Montezuma. The trophy proved an object of terror to the king, who trembled as he looked on the marks of manly strength which its contour and thick curled beard betokened, and ordered it from his presence.

Cortez knew of these events when at Cholula, but had kept them concealed from most of his people. He now adduced them, in select council of his officers, as reason with other matters for the bold step he purposed. This was to seize the person of Montezuma.

On the eighth day after the arrival at the city, Cortez took with him Alvarado, Velasquez de Leon, Avila, Sandoval, and Francisco de Lujo, and, ordering a number of his soldiers to keep in his vicinity, proceeded to the royal palace. He conversed with Montezuma concerning the attack on the garrison at the coast, and professed belief in the Mexican prince’s asseverations that he had no part in it; but added that, to quiet all suspicion on the part of the great emperor of the East, it would be best for him to re move to the Spanish quarters! Montezuma saw at once the degradation to which he was called upon to submit, but looking on the fierce Spaniards around him, and hearing an interpretation of their threats to dispatch him immediately if he did not comply, he suffered himself to be conducted to the palace occupied by his false friends.

To hide his disgrace from his subjects, the unhappy monarch assured the astonished concourse in the streets that he went of his own free will. Cortez, while he kept his prisoner secure by a constant and vigilant guard, allowed him to preserve all the outward tokens of royalty.

See Further:

- Hernando Cortez

- The Zempoallans And Quiavistlans

- Expedition Of Pamphilo De Narvaez

- Siege of the City of Mexico