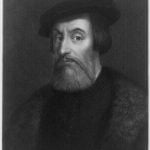

The Cuban governor, Velasquez, determined to pursue discoveries and conquest at the west, and appointed Hernando Cortez, a Spanish cavalier, resident upon the island, to command the new expedition. That the reader may judge what strange contradictions may exist in the character of the same individual, how generosity and cupidity, mildness and ferocity, cruelty and kindness, may be combined, let him compare the after conduct of this celebrated hero with his character as sketched by the historian.

“Cortez was well made, and of an agreeable countenance; and, besides those common natural endowments, he was of a temper which rendered him very amiable; for he always spoke well of the absent, and was pleasant and discreet in his conversation. His generosity was such that his friends partook of all he had, without being suffered by him to publish their obligations.”

In the words of the poet, he

“Was one in whom

Adventure, and endurance, and emprise

Exalted the mind s faculties, and strung

The body s sinews. Brave he was in fight,

Courteous in banquet, scornful of repose,

And bountiful, and cruel, and devout.”

Hidalgos of family and wealth crowded eagerly to join the fortunes of the bold and popular leader. “Nothing was to be seen or spoken of,” says Bernal Diaz, “but selling lands to purchase arms and horses, quilting coats of mail, making bread, and salting pork for sea store.”

From St. Jago the fleet sailed to Trinidad on the southern coast, where the force was increased by a considerable number of men, and thence round Cape Antonio to Havana. From the latter port the flotilla got under weigh on the 10th of February 1519. It consisted of a brigantine and ten other small vessels, whose motley crews are thus enumerated: ” five hundred and eight soldiers, sixteen horse; and of mechanics, pilots, and mariners, an hundred and nine more, besides two chaplains, the licentiate Juan Diaz, and Father Bartholomew De Olmedo, a regular of the order of our Lady de la Merced.” The missile weapons of the party were muskets, crossbows, falconets, and ten small field pieces of brass. The color, quality, and condition of each of the horses is described with great particularity.

The first land made was the island of Cozumel, off the coast of Yucatan. One of the vessels reached the island two days before the rest; and finding the habitations of the natives abandoned, the Spaniards ranged the country, and plundered their huts and temple, carrying off divers small gold images, together with clothes and provisions.

Cortez, on his arrival, strongly reprehended these proceedings, and, liberating three Indians who had been taken prisoners, sent them to seek out their friends, and explain to them his friendly intentions. Their confidence was perfectly restored by this act, and by the restoration of the stolen property; so that the next day, the chief came with his people to the camp, and mingled with the Spaniards on the -most friendly terms.

No further violence was offered to them or their property during the stay of the Spaniards, except that these zealous reformers seized the idols in the temple, and rolling them down the steps, built an altar, and placed an image of the Virgin upon it, erecting a wooden crucifix hard by. The Holy Father, Juan Diaz, then said Mass, to the great edification of the wondering natives.

This temple was a well-built edifice of stone, and contained a hideous idol in somewhat of the human form. “All the idols,” says de Solis, “worshiped by these miserable people, were formed in the same manner; for though they differed in the make and representation, they were all alike most abominably ugly; whether it was that these barbarians had no notion of any other model, or that the devil really appeared to them in some such shape; so that he who struck out the most hideous figure, was accounted the best Workman.”

Seeing that no prodigy succeeded the destruction of their gods, the savages were the more ready to pay attention to the teachings which were so earnestly impressed upon them by the strangers, and appeared to hold the symbols of their worship in some veneration, offering incense before them, as erstwhile to the idols.

Cortez heard one of the Indians make many attempts to pronounce the word Castilla, and, his attention being attracted by the circumstance, he pursued his inquiries until he ascertained that two Spaniards were living among the Indians on the main.

He immediately used great diligence to ransom and re store them to liberty, and succeeded in the case of one of them, named Jeronimo de Aguilar, who occupies an important place in the subsequent details of adventure. The other, one Alonzo Guerrero, having married a wife among the Indians, preferred to remain in his present condition. He said to his companion, ” Brother Aguilar, I am married, and have three sons, and am a Cacique and captain in the wars; go you, in God s name; my face is marked, and my ears bored; what would those Spaniards think of me if I went among them?”

De Solis says of this man, that his natural affection was but a pretense “why he would not abandon those deplorable conveniences, which, with him, weighed more than honor or religion. We do not find that any other Spaniard, in the whole course of these conquests, committed the like crime; nor was the name of this wretch worthy to be remembered in this history; but, being found in the writings of others, it could not be concealed; and his ex ample serves to show us the weakness of nature, and into what an abyss of misery a man may fall when God has abandoned him.”

Poor Aguilar had been eight years a captive: tattooed, nearly naked, and browned by sun, he was scarce distinguishable from his Indian companions; and the only Castilian words which he was at first able to recall were “Dios, Santa Maria,” and “Sevilla.” Still mindful of his old associations and religion, he bore at his shoulder the tattered fragments of a prayer book.

He belonged to a ship’s crew who had been wrecked on the coast, and was the only survivor of the number, except Guerrero. The rest had died from disease and over work, or had been sacrificed to the idols of the country. Aguilar had been “reserved for a future occasion by reason of his leanness,” and succeeded in escaping to another tribe and another master.

Cortez sailed with his fleet, from Cozumel, for the river Tabasco, which was reached on the 13th of March 1519. Urging their way against the current, in the boats and smaller craft, for the principal vessels were left at anchor near the mouth, the whole armament entered the stream. As they advanced, the Spaniards perceived great bodies of Indians, in canoes, and on both banks, whose outcries were interpreted by Aguilar to be expressions of hostility and defiance. Night came on before any attack was made on either side. Next morning, the armament recommenced its progress, in the form of a crescent: the men, protected as well as possible by their shields and quilted mail, were ordered to keep silence, and offer no violence until ordered. Aguilar, who understood the language of these Indians, was commissioned to explain the friendly purposes of his companions, and to warn the natives of the consequences that would result from their opposition. The Indians, with signs of great fury and violence, refused to listen to him, or to grant permission to the Spaniards to supply themselves with wood and water.

The engagement commenced by a shower of arrows from the canoes on the river, and an immense multitude opposed the landing of the troops. Numbers and bravery could not, however, avail against the European skill and implements of warfare. Those in the canoes were easily driven off, and, notwithstanding the difficulties of a wet and marshy shore, where thousands of the enemy lay concealed to spring upon them unawares, the Spanish forces made their way to the town of Tabasco, driving the Indians into the fortress, or dispersing them in the forest. Tabasco was protected in the ordinary Indian style, by strong palisades of trees, a narrow and crooked entrance being left.

Cortez immediately attacked the town, and, by firing through the palisades, his troops soon drove in the bow men who were defending them, and, after a time, got complete possession.

The town was obstinately defended; even after the Spaniards had affected an entrance. The enemy retreated be hind a second barricade, “fronting” the troops, “valiantly whistling and shouting al calachioni, or kill the captain.” They were finally overpowered, and fled to the woods.

Great Battle with the Natives

Hitherto a blind superstition, by which supernatural powers were ascribed to the whites, had quelled the vigor and spirit of the Indians; but an interpreter named Melchorejo, whom Cortez had brought over from Cuba, deserted from the Spaniards during the first night spent in Tabasco, and urged the natives to another engagement. He explained the real nature of the mysterious weapons, whose flash and thunder had created such terror, and disabused the simple savages of the ideas entertained by them of the invulnerable nature of their foes. They proved in the subsequent battles much more dangerous opponents than before. The narrator mentions, with no little satisfaction, the fate of this deserter. His new allies, it seems, ” being vanquished a second time, revenged themselves on the adviser of the war, by making him a miserable sacrifice to their idols.”

All was as still, upon the succeeding day, as if the country was abandoned by its inhabitants; but a party of one hundred men, on a scout, was suddenly surrounded and attacked by such hordes of the enemy, that they might have been cut off from sheer fatigue, but for another company which came to their assistance. As the Spaniards endeavored to retreat to the camp, the Indians would rush upon them in full force, “who, immediately upon their facing about, got out of their reach, retiring with the same swiftness that they were attacked; the motions of this great multitude of barbarians from one side to another, resembling the rolling of the sea, whose waves are driven back by the wind.”

Two of the Spaniards were killed and eleven wounded in the fray: of the Indians, eighteen were seen lying dead on the field, and several prisoners were taken. From these Cortez learned that tribes from all sides were gathered to assist those of Tabasco in a general engagement planned for the next day, and he accordingly made the most diligent preparation to receive them. The horses were brought on shore, and care was taken to restore their animation, subdued by confinement on board ship.

As soon as day broke, mass was said, and the little army was put in motion to advance upon the enemy. They were discovered, marshaled on the vast plain of Cintia, in such numbers that it was impossible to compute them. They extended so far, says Solis, “that the sight could not reach to see the end of them.” The Indian warriors were painted and plumed, their arms were bows and arrows, slings, darts, clubs armed with sharp flints, and heavy wooden swords. The bodies of the leaders were protected by quilted coats of cotton, and they bore shields of tortoise-shell or wood, mounted, in some instances, with gold.

To the sound of rude drums, and the blast of seashells and large flutes, the vast crowd fell furiously upon the Spaniards, and although checked by their more efficient weapons, only retired to a convenient distance for hurling stones and discharging arrows. The field-pieces mowed them down by hundreds; but concealing the havoc by raising clouds of dust, and closing up their ranks with shouts of “ala lala” (the precise sound of the Turkish war-cry, viz., a constant repetition of the word Allah), they held their ground with the most determined courage.

The little handful of cavalry, which, led by Cortez in person, had made a detour to avoid a marsh, now fell upon the Indians from a new quarter, and, riding through and through the crowded mass of savages, so bewildered and amazed them that they fled in dismay. No such animal as the horse had ever before been seen by them. They took the monsters, says Diaz, for centaurs, supposing the horse and his rider to be one.

On the field of battle, as the conquerors passed over it, lay more than eight hundred dead or desperately wounded. But two of the Spaniards were killed, although seventy of their number were wounded at the first rush of the barbarians.

The victors having rendered thanks “to God and to our Lady, his blessed Mother,” for their success, dressed their wounds, and those of the invaluable horses, with the fat of dead Indians, and retired to refresh themselves by food and sleep.

Lopez de Gomara affirms that one of the holy apostles, under the form of Francisco de Morla, appeared upon the field during this bloody engagement, and turned the scale of victory. Diaz says, “It might be the case, and I, sinner as I am, was not permitted to see it. What I did see was Francisco de Morla, in company with Cortez and the rest, upon a chestnut horse. But although I, unworthy sinner that I am, was unfit to behold either of those holy apostles, upwards of four hundred of us were present; let their testimony be taken.” He adds, that he never heard of the incident until he read of it in Gomara’s history.

Several prisoners were taken in this battle, among them two who appeared to be of superior rank. These were dismissed with presents and favors, to carry proposals of peace to their friends. The result was highly satisfactory: fifteen slaves, with blackened faces and ragged attire, “in token of contrition,” came bringing offerings. Permission was given to bury and burn the bodies of those who fell in the terrible slaughter, that they might not be devoured by wild beasts (“lions and tigers,” according to Diaz). This duty accomplished, ten of the caciques and principal men made their appearance, clad in robes of state, and expressed desire for peace, excusing their hostility, as the result of bad advice from their neighbors, and the persuasion of the renegade whom they had sacrificed. Cortez took pains to impress them with ideas of his power and the greatness of the monarch he served; he ordered the artillery to be discharged, and one of the most Spirited of the horses to be brought into the reception-room: “it being so contrived that he should show himself to the greatest advantage, his apparent fierceness, and his action, struck the natives with awe.”

Many more chiefs came in on the following day, bringing the usual presents of little gold figures, the material of which came, they said, from “Culchua,” and from ” Mexico,” words not yet familiar to the ears of the Spaniards.

Twenty women were, moreover, offered as presents, and gladly received by Cortez, who bestowed one upon each of his officers. . They were all duly baptized, and had the pleasure of listening to a discourse upon the mysteries of his faith, delivered for their especial benefit by Father Bartholomew, the spiritual guide of the invaders. Knowing nothing of the language, and having no competent interpreter, it probably made no very vivid impression; but these captives were set down as the first Christian women of the country.

Among them was one young woman of remarkable beauty and intelligence, whom the Spaniards christened Marina. She was said to be of royal parentage, but from parental cruelty, or the fortunes of war, had been held in slavery at a settlement on the borders of Yucatan, where a Mexican fort was established, and afterwards fell into the hands of the Tabascan cacique. She spoke both the Mexican language, and that common to Yucatan and Tabasco, so that Cortez was able, by means of her and Aguilar, to communicate with the inhabitants of the interior, through a double interpretation, until Marina had mastered the Spanish tongue. She accompanied Cortez throughout his eventful career in Mexico, and had a son by him, who was made, says Solis, “a Knight of St. Jago, in consideration of the nobility of his mother s birth.” Before this connection she had been bestowed by the commander upon one Alonzo Puerto Carrero, until his departure for Castile.

Communication with the Mexican Emperor

“Thou too dost purge from earth its horrible

And old idolatries; from their proud fanes

Each to his grave their priests go out, till none

Is left to teach their worship!”

Bryant’s Hymn to Death.

Before his departure from Tabasco, Cortez and his priest made strenuous efforts to explain the principles of his religion to the chiefs and their people. This, indeed, seems really to have been a purpose uppermost in his heart throughout the whole of his bloody campaign; but, as may well be supposed, the subject was too abstract, too novel, and too little capable of proofs, which appeal to the senses and inclinations, to meet with much favor. “They only complied,” says Solis, “as men that were subdued, being more inclined to receive another God than to part with any of their own. They hearkened with pleasure, and seemed desirous to comprehend what they heard; but reason was no sooner admitted by the will than it was rejected by the understanding.” They acknowledged that “this must, indeed, be a great God, to whom such valiant men show so much respect.”

From the river Tabasco the fleet sailed direct for San Juan de Ulua, where they were no sooner moored than two large piraguas, with a number of Indians on board, came boldly alongside. By the interpretation of Marina, Cortez learned that these came in behalf of Pitalpitoque and Tendile, governor and captain of the district, under Montezuma, to inquire as to his purposes, and to make offers of friendship and assistance. The messengers were handsomely entertained, and dismissed with a few presents, trifling in themselves, but of inestimable value in their un-skilful eyes.

As the troops landed, Tendile sent great numbers of his men to assist in erecting huts for their accommodation; a service, which was rendered with remarkable dexterity and rapidity.

On the morning of Easter day, the two great officers came to the camp with a lordly company of attendants. Not to be outdone in parade, Cortez marshaled his soldiers, and having conducted the chiefs to the rude chapel, Mass was said with due ceremony. He then feasted them, and opened negotiations by telling of his great sovereign, Don Carlos, of Austria, (Charles the Fifth,) and expressing a desire to hold communion in his behalf with the mighty Emperor Montezuma,

This proposition met with little favor. Tendile urged him to accept the presents of plumed cotton mantles, gold, &c., which they had brought to offer him, and depart in peace. Diaz says that the Indian commander expressed haughty astonishment at the Spaniard’s presumption. Cortez told them that he was fully resolved not to leave the country without obtaining an audience from the emperor; but, to quiet the apprehension and disturbance of the Indians, he agreed to wait until a message could be sent to the court and an answer returned, before commencing further operations.

Painters, whose skill Diaz enlarges upon, now set to work to depict upon rolls of cloth, the portraits of Cortez and his officers, the aspect of the army, the arms, and other furniture, the smoke poured forth from the cannon, and, above all, the horses, whose “obedient fierceness” struck them with astonishment. These representations were for the benefit of Montezuma, that he might learn more clearly than he could by verbal report, the nature of his novel visitants. By the messengers, Cortez sent, as a royal present, a crimson velvet cap, with a gold medal upon it, some ornaments of cut glass, and a chair of tapestry.

Pitalpitoque now settled himself, with a great company of his people, in a temporary collection of huts, built in the immediate vicinity of the Spanish camp, while Tendile attended to the delivery of the message to his monarch. Diaz says that he went to the royal court, at the city of Mexico, in person, being renowned for his swiftness of foot; but the most probable account is that he availed himself of a regular system of couriers, established over the more important routes throughout the empire. However this may be, an answer was returned in seven days time, the distance between Mexico and San Juan being sixty leagues, by the shortest road.

With the messenger returned a great officer of the court, named Quintalbor, who bore a most striking resemblance to Cortez, and one hundred other Indians, loaded with gifts for the Spaniards. Escorted by Tendilo, the embassy arrived at the camp, and, after performing the usual ceremony of solemn salutations, by burning incense, &c., the Mexican lords caused mats to be spread, and displayed the gorgeous presents they had brought.

These consisted of beautifully woven cotton cloths; ornamental work in feathers, so skillfully executed that the figures represented had all the effect of a painting; a quantity of gold in its rough state; images wrought or cast in gold of various animals; and, above all, two huge plates, one of gold, the other of silver, fancifully chased and embossed to represent the sun and moon. Diaz says that the golden sun was of the size of a carriage wheel, and that the silver plate was still larger.

Proffering these rich tokens of good will, together with numerous minor articles, the chiefs delivered their monarch’s mission. Accompanied by every expression of good will, his refusal was declared to allow the strangers to visit his court. Bad roads and hostile tribes were alleged to constitute insuperable difficulties, but it was hinted that more important, though unexplainable reasons existed why the interview could not take place.

Cortez, courteously, but firmly, persisted in his determination, and dismissed the ambassadors with renewed gifts; expressing himself content to await yet another message from Montezuma. He said that he could not, without dishonoring the king, his master, return before having personal communication with the emperor.

He, meantime, sent a detachment farther up the coast, with two vessels, to seek for a more convenient and healthy place of encampment than the burning plain of sand where the army was now quartered.

Montezuma persisted in objections to the advance of the Spaniards, and Cortez being equally immovable in his determination to proceed, the friendly intercourse hither to maintained between the natives and their guests now ceased. Tendile took his leave with some ominous threats, and Pitalpitoque with his people departed from their temporary domiciles.

The soldiers cut off from their former supplies of pro vision, and seeing nothing but danger and privation in store for them, began to rebel, and to talk of returning home. Cortez checked this movement by precisely the same policy that was resorted to by Agamemnon and Ulysses, under somewhat similar circumstances, as will be found at large in the second book of the Iliad, line 110 et seq.

He seemed to assent to the arguments of the spokesman of the malcontents, and proceeded to proclaim his purpose of making sail for Cuba, but, in the meantime, engaged the most trusty of his friends to excite a contrary feeling among the troops. The effort was signally successful: the commander graciously consented to remain, and lead them to further conquests, expressing his great satisfaction in finding them of such bold and determined spirit.