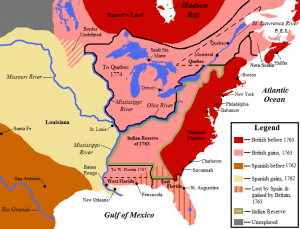

After the peace, concluded between France and England in 1748, the French, excluded from the Atlantic coast of North America, designed to take possession of the country further west, and for this purpose, commenced to build a chain of forts to connect the St. Lawrence and the Mississippi rivers. The English, to prevent this scheme from being carried into action, formed an Ohio company, to whom a considerable extent of country was granted by the English government. Upon hearing of this, the governor of Canada notified the governors of New York and Pennsylvania, that if the English traders came upon the western territory, they would be seized or killed.

This menace did not divert the Ohio company from prosecuting its design of surveying the country as far as the falls in the Ohio river. While Mr. Gist was making that survey for the company, some French parties, with their Indians, seized three British traders, and carried them to Presque Isle, on Lake Erie, where a strong fort was then erecting. The British, alarmed at this capture, retired to the Indian towns for shelter; and the Twightwees, resenting the violence done to their allies, assembled, to the number of five hundred or six hundred, scoured the woods, and, finding three French traders, sent them to Pennsylvania. The French determined to persist; built a strong fort, about fifteen miles south of the former, on one of the branches of the Ohio; and another still, at the confluence of the Ohio and Wabache; and thus completed their long projected communication between the mouth of the Mississippi and the river St. Lawrence. Thus began the fight known as the French and Indian War.

The Ohio company complained loudly of these aggressions on the country which had been granted to it as part of the territory of Virginia: Robert Dinwiddie, lieutenant governor of that colony, considered the encroachment as an invasion of his province, and judged it his duty to demand, in the name of the king, that the French should desist from the prosecution of designs, which he considered as a violation of the treaties subsisting between the two crowns. This service, it was foreseen, would be rendered very fatiguing and hazardous by the extensive tract of country, almost entirely unexplored, through which an envoy must pass, as well as by the hostile dispositions of some of the Indian inhabitants, and the doubtful attachments of others. Uninviting, however, and even formidable, as it was, a regard to the intrinsic importance of the territory in question, with extensive views into the future interest of the American colonies, incited an enterprising and public spirited young man to undertake it. George Washington, then in his twenty-second year, instantly engaged in the difficult and perilous service. Attended by one person only, he set out from Williamsburg on the 31st of October. The season was uncommonly severe, and the length of his journey was above four hundred miles, two hundred of which lay through a trackless desert, inhabited by Indians. On the 14th of November, he arrived at Will’s’ creek, then, the exterior settlement of the English, where he procured guides to conduct him over the Allegheny mountains; and, after being considerably impeded by the snow and high water, he, on the 22d, reached the mouth of Turtle creek, on the Monongahela. Pursuing his route, he ascended the Allegheny River, and at the mouth of French creek found the first fort occupied by the troops of France. Proceeding up the creek to another fort, he was received, on the 12th of December, by M. Lagardier de St. Pierre, commanding officer on the Ohio, to whom he delivered the letter of Governor Dinwiddie. The chief officers retired, to hold a council of war; and Washington seized that opportunity of taking the dimensions of the fort, and making all possible observations.

Having received a written answer for the Virginia governor, he returned to Williamsburg. The answer of St. Pierre stated, that he had taken possession of the country by direction of the governor general of Canada; that he would transmit Governor Dinwiddie’s letter to him; and that to his orders he should yield implicit obedience.

The conclusion of Washington’s expedition is thus described by himself, in his journal:

“Our horses were now so weak and feeble, and the baggage so heavy, (as we were obliged to provide all the necessaries which the journey would require,) that we doubted much their performing it. Therefore, myself and others, except the drivers, who were obliged to ride, gave up our horses for packs, to assist along with the baggage. I put myself in an Indian walking dress, and continued with them three days, until I found there was no probability of their getting home in any reasonable time. The horses became less able to travel every day; the cold, in-creased very fast; and the roads were becoming much worse by a deep snow, continually freezing: therefore, as I was uneasy to get back, to make report of my proceedings to his honor the governor, I determined to prosecute my journey, the nearest way through the woods, on foot.

“Accordingly, I left Mr. Vanbraam in charge of our baggage, with money and directions to provide necessaries from place to place for themselves and horses, and to make the most convenient dispatch in traveling.

“I took my necessary papers, pulled off my clothes, and tied myself up in a watch coat. Then, with gun in hand, and pack on my back, in which were my papers and provisions, I set out with Mr. Gist, fitted in the same manner, on Wednesday, the 26th. The day following, just after we had passed a place called Murdering town, (where we intended to quit the path and steer across the country for Shanapin’s town,) we fell in with a party of French Indians, who had laid in wait for us. One of them fired at Mr. Gist or me, not fifteen steps off, but fortunately missed. We took this fellow into custody, and kept him until about nine o’clock at night, then let him go, and walked all the remaining part of the night without making any stop, that we might get the start, so far as to be out of the reach of their pursuit the next day, since we were well assured they would follow our track as soon as it was light. The next day we continued travelling until quite dark, and got to the river about two miles above Shanapin’s. We expected to have found the river frozen, but it was not, only about fifty yards from each shore. The ice, I suppose, had broken up above, for it was driving in vast quantities.

“There was no way for getting over but on a raft, which we set about, with but one poor hatchet, and finished just after sun setting. This was a whole day’s work: we next got it launched, then went on board of it, and set off; but, before we were half way over, we were jammed in the ice, in such a manner, that we expected every moment our raft to sink, and ourselves to perish. I put out my setting pole to try to stop the raft that the ice might pass by, when the rapidity of the stream threw it with so much violence against the pole, that it jerked me out into ten feet water; but I fortunately saved myself by catching hold of one of the raft logs. Notwithstanding all our efforts, we could not get to either shore, but were obliged, as we were near an island, to quit our raft and make to it.

“The cold was so extremely severe, that Mr. Gist had all his fingers, and some of his toes frozen, and the water was shut up so hard, that we found no difficulty in getting off the island on the ice in the morning, and went to Mr. Frazier’s. We met here with twenty warriors, who were going to the southward to war; but coming to a place on the head of the Great Kanawa, where they found seven people killed and scalped, (all but one woman with very light hair,) they turned about and ran back, for fear the inhabitants should rise and take them as the authors of the murder. They report, that the bodies were lying about the house, and some of them much torn and eaten by the hogs. By the marks which were left, they say they were French Indians of the Ottawa nation, &c.; who did it.

“As we intended to take horses here, and it required some time to find them, I went up about three miles to the mouth of Yohogany, to visit Queen Alliquippa, who had expressed great concern that we had passed her in going to the fort. I made her a present of a watch coat and a bottle of rum, which latter was thought much the best present of the two.

“Tuesday, the 1st of January, we left Mr. Frazier’s house, and arrived at Mr. Gist’s, at Monongahela, the 2d, where I bought a horse, saddle, &c. The 6th, we met seventeen horses loaded with materials and stores for a fort at the forks of Ohio, and the day after, some families going out to settle. This day, we arrived at Wills’ s Creek, after as fatiguing a journey as it is possible to conceive, rendered so by excessive bad weather. From the 1st day of December to the 15th, there was but one day on which it did not rain or snow incessantly; and throughout the whole journey, we met with nothing but one continued series of cold, wet weather, which occasioned very uncomfortable lodgings, especially after we had quitted our tent, which was some screen from the inclemency of it.

“On the 11th, I got to Belvoir, where I stopped one day to take necessary rest; and then set out and arrived in Williamsburg the 16th, when I waited upon his honor the governor, with the letter I had brought from the French commandant, and to give an account of the success of my proceedings. This I beg leave to do by offering the foregoing narrative, as it contains the most remarkable occurrences which happened in my journey.”

The answer from the French commandant brought by Washington was the signal for active measures. A regiment was immediately raised for the service by the government of Virginia, and George Washington, who was appointed lieutenant-colonel, marched, in April, 1754, for the Great Meadows, lying within the disputed territory. Hearing that the French had erected a fort at the junction of the Allegheny and Monongahela, he judged that this was a hostile movement; and, availing himself of the offered guidance of Indians, Washington marched, with his detachment, to the Great Meadows, where he surprised a French detachment, and captured the whole of it.

At the Great Meadows, Washington built Fort Necessity. While he was engaged in surrounding it with a ditch, about fifteen hundred French and Indians, under command of M. do Villiers, appeared and commenced a furious attack. The defense was maintained with bravery from ten in the morning until dark, when De Villiers demanded a parley, and in the course of the night the garrison capitulated. Washington and his men were permitted to march out without molestation, and with the honors of war. In this attack, it is supposed, the French commander lost two hundred men, killed and wounded. The loss of the gallant garrison was only fifty-eight men killed and wounded.

The English erected a fort on Wills’ creek soon after this affair, and made extensive preparations for the struggle which seemed impending. A union of the colonies was formed, for purposes of offense and defense, and the friendship of a portion of the Six Nations secured. But the dissensions of the colonial governments caused the union to be rejected, and the war was left to the prosecution of the British troops and such aid as each colony might choose to offer.

In the north, about six hundred Indians invaded Hoosack, and burned and plundered without mercy. The Scatecook tribe instigated the Orondocks and others to this invasion. Some of their allies were descended from the Connecticut River Indians, who were drawn from their country in Philip’s war. Major General Winslow had entered into a treaty with the eastern tribes immediately previous to the invasion.

Early in 1755, General Braddock, with a respectable body of British troops, arrived in America; and a convention of the colonial governors was held in Virginia, at his request, to fix the plan of military operations. Three expeditions were designed, one against Fort Duquesne, at the junction of the Allegheny and Monongahela, to be conducted by General Braddock; the second, an attempt on the fort at Niagara, to be conducted by Governor Shirley; and the third, an attempt to capture Crown Point, to be executed by the militia of the northern colonies.

General Braddock might have entered upon action early in the spring; but the contractors for the army not seasonably providing a sufficient quantity of provisions, nor a competent number of wagons, for the expedition, the troops could not be put in motion until June. On the 10th of that month, the general began his march from a post on Wills’ creek, at the head of about twenty-two hundred men. The additional delay that must be occasioned in opening a road through an extremely rough country, with an apprehension of a reinforcement of Fort Duquesne, induced a resolution to hasten the march of a part of the army to the point of destination. The general, at the head of twelve hundred men, selected from the different corps, with ten pieces of cannon and the necessary ammunition and provisions, marched forward; leaving the residue of the army under the command of Colonel Dunbar, to follow, with all the heavy baggage, by slow and easy marches. Such, however, were the natural and necessary impediments, that Braddock did not reach the Monongahela until the 8th of July. The next day he expected to invest Fort Duquesne; and in the morning made a disposition of his forces conformable to that expectation. His army composed of three hundred British regulars, was commanded by Lieutenant-colonel Gage, and he followed, at some distance, with the artillery and main body of the army, divided into small columns.

Colonel Dunbar was then nearly forty miles behind him. This circumstance alone evidently required caution. But the nature of the country over which the troops were to be conducted, and the character of the enemy to be encountered, rendered circumspection indispensably necessary. The general was cautioned by Washington, of the sources of danger, and advised to advance in his front the provincial troops in his army, consisting entirely of independent and ranging companies, to scour the woods and guard against an ambuscade; but he thought too contemptuously both of the enemy and of the provincials, to follow that salutary advice. Heedless of danger, he pressed forward; the distance of seven miles still intervening between his army and the anticipated place of action. At this in-suspicious moment, in an open wood, thick set with high grass, his front was attacked by an unseen enemy. The van was thrown into some confusion; but the general having ordered up the main body, and the commanding officer of the enemy having fallen, the attack was suspended, and the assailants were supposed to be dispersed. The attack, however, was renewed with increased fury; the van fell back on the main body; and the whole army was thrown into confusion. The general, if deficient in other military virtues, was not destitute of courage; but, at this embarrassing moment, personal valor afforded a very inadequate security. An instant retreat, or a rapid charge without observance of military rules, seems to have been imperatively necessary; but neither of these expedients was adopted. The general, under an incessant and galling fire, made every possible exertion to form his broken troops on the very ground where they were first attacked; but his efforts were fruitless. Every officer on horseback, excepting Colonel Washington, who was aid-de-camp to the commander-in-chief, was either killed or wounded. After an action of three hours, General Braddock, under whom three horses had been killed, received a mortal wound; and his troops fled, in extreme dismay and confusion. The provincials, who were among the last to leave the field, formed after the action by the prudent valor of Washington, and covered the retreat of the regulars. The defeat was entire. Of eighty-five officers, sixty-four were killed and wounded, and about half the privates. The defeated army fled precipitately to the camp of Dunbar, where Braddock expired of his wounds. The British troops were soon after marched to Philadelphia, where they went into winter quarters.

In August of this year, General William Johnson, with between five and six thousand men, English and Mohawks, proceeded upon the expedition for the reduction of Crown Point. Having pitched his camp at the south end of Lake George, he learned that a large body of French and Indians was advancing towards him from Ticonderoga. The Baron Dieskau, lately appointed commander of the French forces, hearing of the intended expedition against Crown Point, resolved to prevent it by a counter movement. He embarked at Crown Point, with two thousand men, and landing at South Bay, marched for Fort Edward, which had been built by the English a short time previous. But the Canadians and Indians were opposed to attacking a regularly furnished fortress, and Dieskau changed his route and marched against the camp of Johnson. The English general heard of his approach, and sent out Colonel Ephraim Williams with twelve hundred men, to meet him. The baron’s skill was displayed in his arrangement to receive this detachment. Keeping the regulars with him in the center, the Canadians and Indians were ordered to advance through the woods upon the right and left, so as to enclose the enemy. The Mohawk scouts of the English, prevented the full success of this design; but, as the enemy approached they were so hotly received, and suffered such a terrible loss, that they made a precipitate retreat. Colonel Williams was among the slain. Hendrick, the celebrated Mohawk chief, with a number of his Indians died fighting bravely.

After this success, Dieskau pressed on to encounter the main body of the English, who had erected a breastwork and made other preparations for an attack. The regular French troops made the central assault upon the breastwork, and the Canadians and Indians attacked the flanks. The English determined upon a desperate defense; and as soon as their cannon began to play upon the enemy, they forced the French general to order a retreat, and his troops retiring in confusion, were attacked in the rear and almost dispersed. Their rout was completed by the arrival of two hundred New Hampshire militia, under Captain McGrinnes. Dieskau, dangerously wounded, was taken prisoner. Captain McGrinnes fell in the attack. This repulse revived the spirits of the colonists; but the success was not improved, and Shirley’s expedition against Niagara failed for want of concert and rapidity in making preparations.

The campaign of 1756 began with vigorous preparations for various expeditions. Baron Dieskau had been succeeded by the bold and skilful Marquis de Montcalm, whose movements anticipated those of the English generals. On the 10th of August, he approached Fort Ontario, with more than five thousand regulars, Canadians, and Indians. Having made the necessary dispositions, he opened the trenches on the 12th, at midnight, with thirty-two pieces of cannon, besides several brass mortars and howitzers. The garrison having fired away all their shells and ammunition, Colonel Mercer, the commanding officer, ordered the cannon to be spiked up, and crossed the river to Little Oswego Fort, without the loss of a single man. The enemy, taking immediate possession of the deserted fort, began to fire from it, which was kept up without intermission. About four miles and a half up the river was Fort George, the defense of which was committed to Colonel Schuyler. On the abandonment of the first fort by Colonel Mercer, about three hundred and seventy of his men had joined Colonel Schuyler, in the intention of having an intercourse between his fort and that to which their own commander retreated; but a body of twenty-five hundred Canadians and Indians boldly swam across the river, in the night between the 13th and 14th, and cut off that communication, On the 13th, Colonel Mercer was killed by a cannon ball. The garrison, deprived of their commander, who was an officer of courage and experience, frustrated in their hope of aid, and destitute of a cover to their fort, demanded a capitulation on the following day, and surrendered as prisoners of war. They were the regiments of Shirley and Pepperell, and amounted to fourteen hundred men. The conditions, required and acceded to, were, that they should be exempted from plunder; conducted to Montreal; and treated with humanity. No sooner was Montcalm in possession of the two forts at Oswego, than, with admirable policy, he demolished them in the presence of the Indians of the Six Nations, in whose country they had been erected, and whose jealousy they had excited. This event entirely disconcerted the English plan of operations, and they attempted nothing further during the year. Fort Granby, on the confines of Pennsylvania, was surprised by a party of French and Indians, who made the garrison prisoners. Instead of scalping the captives, they loaded them with flour, and drove them into captivity. The Indians on the Ohio having killed above one thousand of the inhabitants of the western frontiers, were soon chastised with military vengeance. Colonel Armstrong, with a party of two hundred and eighty provincials, marched from Fort Armstrong, which had been built on the Juniata river, about one hundred and fifty miles west of Philadelphia, to Kittaning, an Indian town, the rendezvous of those murdering Indians, and destroyed it. Captain Jacobs, the Indian chief, defended himself through loop holes of his log house. The Indians refusing the quarter which was offered them, Colonel Armstrong ordered their houses to be set on fire; and many of the Indians were suffocated and burnt; others were shot in attempting to reach the river. The Indian captain, his squaw, and a boy called the King’s Son, were shot as they were getting out of the window, and were all scalped. It was computed, that between thirty and forty Indians were destroyed. Eleven English prisoners were released.

Lord Loudoun, the English commander-in-chief, made considerable exertion to raise a sufficient force to carry out his designs; but he directed all his disposable force against Louisbourg, which was found to be almost impregnable, while Montcalm was active in another quarter. The general inefficiency of this commander was made manifest by his career. Thus far, he had effected nothing.

The Marquis de Montcalm, availing himself of the absence of the principal part of the British force, advanced with an army of nine thousand men, and laid siege to Fort William Henry. The garrison at this fort consisted of between two and three thousand regulars, and its fortifications were strong and in very good order. For the farther security of this important post, General Webb was stationed at Fort Edward with an army of four thousand men. The French commander, however, urged his approaches with such vigor, that, within six days after the investment of the fort, Colonel Monroe, the commandant, after a spirited resistance, surrendered by capitulation. The garrison was to be allowed the honors of war, and to be protected against the Indians until within the reach of Fort Edward; but no sooner had the soldiers left the place, than the Indians in the French army, disregarding the stipulation, fell upon them, and committed the most cruel outrages.

Whether Montcalm could have prevented these cruelties, is a question upon which historians differ. It seems that the Indians served in this expedition, on the promise of plunder; and being prevented from plundering by the terms granted the garrison, they resolved to violate them. Accordingly, they stripped the unarmed English, and murdered all who made any resistance. Out of two hundred men in the New Hampshire regiment, which formed the rear, eighty were killed or taken. The acknowledged virtues of Montcalm should create a presumption in his favor, only to be removed by clear proof of his guilt.

This event aroused the colonists to fresh exertions. The details of the massacre were exaggerated, and the hatred of the French and their savage allies greatly increased. Nineteen hundred men, under Colonel Stanwix, were ordered for the protection of the western frontiers. Troops were raised in all quarters, and early in 1758, General Abercrombie could command the services of fifty thousand men the largest army yet seen in the colonies. Three expeditions were projected; one against Louisbourg, another against Ticonderoga and Crown Point, and the third against Fort Duquesne.

Louisbourg was captured by the English fleet, under Admiral Boscawen, and the land force, under General Amherst, after a siege extending from the 2d of June until the 26th of July. The Chevalier de Drucourt, with about three thousand men, defended the place until it was but a mass of ruins. This was considered the most important triumph of the war.

The army destined for the attack upon Ticonderoga and Crown Point, consisted of fifteen thousand men, attended by a formidable train of artillery, and was commanded by General Abercrombie. Crossing Lake George on the 5th of July, Abercrombie directed his first operations against Ticonderoga. In marching through the woods, the columns became entangled with each other. Lord Howe, at the head of the right center column, fell in with the advanced guard of the enemy, and attacked it with such vigor as to kill, capture, or disperse the whole of it. Lord Howe fell at the first fire. An ill-judged assault was soon after made upon Ticonderoga, but such had been the measures adopted by the French and Indians, that the English were repulsed with the loss of twenty-five hundred men killed and wounded. The loss of the enemy was inconsiderable.

The reduction of Fort Duquesne was the next object accomplished. General Forbes, to whom this enterprise was entrusted, had marched early in July from Philadelphia at the head of the army destined for the expedition; but, such delays were experienced, it was not until September that the Virginia regulars, commanded by Colonel Washington, were commanded to join the British troops at Ray’s town. Before the army was put in motion, Major Grant was detached with eight hundred men, partly British and partly provincials, to reconnoiter the fort and the adjacent country. Having invited an attack from the French garrison, this detachment was surrounded by the enemy; and after a brave defense, in which three hundred men were killed and wounded; Major Grant and nineteen other officers were taken prisoners. General Forbes with the main army, amounting to at least eight thousand men, at length moved forward from Ray’s town; but did not reach Fort Duquesne until late in November. On the evening preceding his arrival, the French garrison, deserted by their Indians and unequal to the maintenance of the place against so formidable an army, had abandoned the fort, and escaped in boats down the Ohio. The English now took possession of that important fortress, and, in compliment to the popular minister, called it Pittsburg. No sooner was the British flag erected on it, than the numerous tribes of the Ohio Indians came in, and made their submission to the English. General Forbes, having concluded treaties with those natives, left a garrison of provincials in the fort, and built a blockhouse near Loyal Hannan; but, worn out with fatigue, he died before he could reach Philadelphia.

While the entrenchments of Abercrombie enclosed him in security, M. de Montcalm was active in harassing the frontiers, and in detaching parties to attack the convoys of the English. Two or three convoys having been cut off by these parties, Major Rogers and Major Putnam made excursions from Lake George to intercept them. The enemy, apprized of their movements, had sent out the French partisan Molang, who had laid an ambuscade for them in the woods. While proceeding in single file in three divisions, as Major Putnam, who was at the head of the first, was coming out of a thicket, the enemy rose, and with discordant yells and whoops attacked the right of his division. Surprised, but not dismayed, he halted, returned the fire, and passed the word for the other divisions to advance for his support. Perceiving it would be impracticable to cross the creek, he determined to maintain his ground. The officers and men, animated by his example, behaved with great bravery. Putnam’s fuse at length missing fire, while the muzzle was presented against the breast of a large and well proportioned Indian; this warrior, with a tremendous war whoop, instantly sprang forward with his lifted hatchet, and compelled him to surrender, and, having disarmed him and bound him fast to a tree, returned to the battle. The enemy were at last driven from the field, leaving their dead behind them; Putnam was untied by the Indian who had made him prisoner, and carried to the place where they were to encamp that night. Besides many outrages, they inflicted a deep wound with a tomahawk upon his left cheek. It being determined to roast him alive, they led him into a dark forest, stripped him naked, bound him to a tree, piled combustibles at a small distance in a circle round him, and, with horrid screams, set the piles on fire. In the instant of an expected immolation, Molang rushed through the crowd, scattered the burning brands, and unbound the victim. The next day Major Putnam was allowed his moccasins, and permitted to march without carrying any pack; at night the party arrived at Ticonderoga, and the prisoner was placed under the care of a French guard. After having been examined by the Marquis de Montcalm, he was conducted to Montreal by a French officer, who treated him with the greatest indulgence and humanity. The capture of Fort Frontenac affording occasion for an exchange of prisoners, Major Putnam was set at liberty.

During these important military operations, the French incited the eastern Indians to begin hostilities, but their attacks were repulsed, by the vigilance and activity of Governor Pownall. The governors of Pennsylvania and New Jersey, with Sir William Johnston, and other agents, concluded a treaty in October, with nearly all the powerful tribes of the territory between the Appalachian Mountains and the lakes. As the French depended upon the support of these Indians, to maintain their western garrisons, this treaty weakened them so much, that they successively fell into the hands of the English.

In 1759, General Amherst succeeded Abercrombie as commander-in-chief of the English forces. The great project of the immediate conquest of Canada was then formed. Three powerful armies, under the command of Amherst, Wolfe and Prideaux, were to enter Canada about the same time. We shall not detail the events which led to the execution of the plans of the English. The Indians were employed by the French up to the latest hour of their authority in North America; and the English also secured the services of a strong body of them, to form part of the army of General Prideaux.

In prosecution of the enterprise against Niagara, General Prideaux had embarked with an army on Lake Ontario and on the 6th of July, landed without opposition within about three miles from the fort, which he invested in form. While directing the operations of the siege, he was killed by the bursting of a cohorn and the command devolved on Sir William Johnson. That general, prosecuting with judgment and vigor the plan of his predecessor, pushed the attack of Niagara with such intrepidity, as soon brought the besiegers within a hundred yards of the covered way. Meanwhile, the French, alarmed at the danger of losing a post, which was a key to their interior empire in America, had collected a large body of regular troops, from the neighboring garrisons of Detroit, Venango, and Presque Isle, with which and a party of Indians they resolved, if possible, to raise the siege. Apprized of their intention to hazard a battle, General Johnson ordered his light infantry, supported by some grenadiers and regular foot, to take post between the cataract of Niagara and the fortress; placed the auxiliary Indians on his flanks; and, together with this preparation for an engagement, took effectual measures for securing his lines, and bridling the garrison. About nine in the morning of the 24th of July, the enemy appeared, and the horrible sound of the war whoop from the hostile Indians was the signal of battle. The French charged with great impetuosity, but were received with firmness; and in less than an hour were completely routed. This battle decided the fate of Niagara. Sir William Johnson, the next morning, sent a trumpet to the French commandant; and in a few hours a capitulation was signed. The garrison, consisting of six hundred and seven men, were to march out with the honors of war, to be embarked on the lake, and carried to New York; and the women and children were to be carried to Montreal. The reduction of Niagara effectually cut off the communication between Canada and Louisiana.

At this last period of the war, the St. Francis Indians suffered severely for their cruelty and perfidy. This tribe was notoriously attached to the French, and had, for near a century, harassed the frontiers of New England, barbarously and indiscriminately killing persons of all ages and of each sex, when there was not the least suspicion of their approach. Captain Kennedy, having been sent with a flag of truce to these Indians, was made a prisoner by them, with his whole party. To chastise them for this outrage, General Amherst ordered Major Robert Rogers to take a detachment of two hundred men, and proceed to Misisque Bay, and to march thence and attack their settlements on the south side of the river St. Lawrence. In pursuance of these orders, he set out on the 13th of September with the detachment for St. Francis, and on the twenty-second day after his departure, in the evening, he came in sight of the Indian town St. Francis. At eight in the evening, he, with a lieutenant and ensign, reconnoitered the town; and, finding the Indians “in a high frolic or dance,” returned to his party at two, and at three marched it within five hundred yards of the town, where he lightened the men of their packs, and formed them for the attack. At half an hour before sunrise he surprised the town, when the Indians were all fast asleep, and destroyed most of them. A few, who were making their escape by taking to the water, were pursued, and both they and their boats were sunk. A little after sunrise, Major Roberts set fire to all their houses, except three, in which there was corn, which he reserved for the use of his men. A number of Indians, who had concealed themselves in the cellars and lofts of their houses, were consumed in the fire. By about seven in the morning, the affair was completed. Two hundred Indians, at least, were killed, and twenty of their women and children taken prisoners. Five only of the last, two Indian boys and three Indian girls, Rogers brought away, leaving the rest to their liberty. He likewise retook five English captives, whom he also took under his care. Of his party, Captain Ogden was badly wounded, six men were slightly wounded, and one Stockbridge Indian was killed.

The war was virtually concluded by the fall of Quebec, in 1759. The Indians knew their weakness, and would not maintain a contest against the overpowering force the English now had in the field, and, therefore, the greater portion of them came and made peace, or according to their own expression, “buried the hatchet.”