Lewis Solomon was the youngest son of William Solomon, 1 who was born in the closing years of the last century, of Jewish and Indian extraction. This William Solomon lived for a time in Montreal, but entered the service of the North-West Company and drifted to the “Sault’, and Mackinaw. Having become expert in the use of the Indian tongue, he was engaged by the British Government as Indian interpreter at the latter post during the War of 1812. During his sojourn at Mackinaw he married a half-breed woman named Miss Johnston, 2 the union resulting in a family of ten children, of whom, at the first writing of these notes, Lewis was the sole survivor, but joined the majority March 9th, 1900. Lewis very humorously claimed that in his person no less than five nationalities are represented, though he fails to tell us how. As the Indian nature appeared to predominate, and since his father was partly German, his mother must have been of very mixed nationality.

When the British forces were transferred to Drummond Island, Interpreter Solomon and his family accompanied them thither; and later, when it was decided that Drummond Island was in U.S. territory, he followed the British forces to Penetanguishene in 1828, where he subsequently died, and where he and his wife and the majority of his family lie buried. It was the fond hope of the family that Louie would succeed his father in the Government service as Indian interpreter. In pursuance of this plan, his father sent him to a French school at L’Assomption; 3 to the Indian schools at Cobourg and Cornwall; also, for a term, to the Detroit “Academy”; so that Louie became possessed of a tolerably fair education, and was regarded by his compatriot half-breeds and French-Canadians as exceedingly clever and a man of superior attainments. Though his memory appears almost intact, the reader may find in his narrative a little disregard for the correct sequence of events, and a tendency to get occurrences mixed, which is not surprising when the length of time is considered. As Louie’s command of English is somewhat above the average of that of his fellow voyageurs, he is permitted to present his narrative, with few exceptions, in his own words.

Narrative of Lewis Solomon

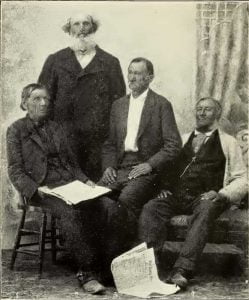

1. Lewis Solomon, born on Drummond Island, 1821; died at Victoria Harbor, Ont., March 1900.

2. John Bussette / Brissette, born in the Rocky Mountains (near Calgary), 1823.

3. James Larammee, born on Drummond Island, 1826.

4. Francis Dusome, born at Fort Garry, Red River, 1820.

My name is Lewis Solomon-spelled L-e-w-i-s-though they call me Louie. I was born on Drummond Island in 1821, moved to St. Joseph Island in 1825, back to Drummond Island again, and then to Penetanguishene in 1829. My father’s name was William Solomon, Government interpreter. His father, Ezekiel Solomon, was born in the city of Berlin, Germany, came to Montreal and went up to the “Sault.” My father was appointed Indian interpreter by the British Government and was at Mackinaw during the War of 1812, then moved to Drummond Island with the British forces, and afterwards to Penetanguishene. My mother’s maiden name was Johnston, born in Mackinaw, where she and my father were married. She died in Penetanguishene. My father received his discharge under Sir John Colborne, retiring on a pension of seventy-five cents a day after a continued service of fifty-six years with the Government, and he died at Penetanguishene also.

When the military forces removed from Drummond Island to Penetanguishene, the Government authorities chartered the brig Wellington to carry the soldiers, military and naval supplies, and government stores; but the vessel was too small, and they were obliged to charter another vessel, and my father was instructed by the Government to charter the schooner Hackett (Alice) commanded by the owner, Capt. Hackett.

On her were placed a detachment of soldiers, some military supplies, and the private property of my father, consisting of two span of horses, four cows, twelve sheep, eight hogs, harness and household furniture. A French-Canadian named Lepine, his wife and child, a tavern-keeper named Fraser, with thirteen barrels of whiskey, also formed part of the cargo. The captain and his crew and many of the soldiers became intoxicated, and during the following night a storm arose, during which the vessel was driven on a rock known as “Horse Island” (Fitzwilliam) near the southernmost point of Manitoulin Island. The passengers and crew, in a somewhat advanced stage of drunkenness, managed to reach the shore in safety; also one horse, some pork, and the thirteen barrels of whiskey, though the whole company were too much intoxicated to entertain an intelligent idea of the operation, but were sufficiently conscious of what they were doing to secure the entire consignment of whiskey. The woman and her infant were left on the wreck, as her husband, Pierre Lepine, was on shore drunk among the others, too oblivious to realize the gravity of the situation, or to render any assistance. Mrs. Lepine, in the darkness and fury of the storm, wrapped the babe in a blanket, and having tied it on her back, lashed herself securely to the mast, and there clung all night long through a furious storm of wind and drenching rain, from eleven o’clock till daylight, or about six o’clock in the morning, when the maudlin crew, having recovered in a measure from their drunken stupor, rescued her from her perilous position in a yawl boat. Such an experience on the waters of Lake Huron, in the month of November, must have certainly bordered on the tragical. The vessel and the remainder of the cargo proved a total loss. The lurching of the schooner from side to side pitched the big cannon down the hatch way, going clear through the bottom, thus, together with pounding on the rocks, completing the wreck. The horse, a fine carriage roadster, remained on the island for several years. My father offered a good price to any one who would bring him away, but he never got him back, and he finally died on the island. This circumstance gave it the name of Horse Island. The infant lived to grow up and marry among the later settlers, but I do not remember to whom, neither do I know what became of her. Fraser, who owned the whiskey, started a tavern in Penetanguishene, near the Garrison cricket ground, where the old mail-carrier, Francis Dusseaume 4 afterwards lived. Slight traces of the building are still to be seen.

My father came to Penetanguishene in another vessel with the officers and soldiers. The rest of the family left Drummond Island the next spring (1829). We started on the 25th of June and arrived at Penetanguishene on the 13th of July, coming in a bateau around by the north shore, and camping every night on the way.

My mother, brother Henry and his wife and eight children, myself, Joseph Gurneau and his wife, and two men hired to assist (Francis Gerair, a French-Canadian, and Gow-bow, an Indian), all came in one bateau. We camped one night at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s fort at Killarney. We landed at the Barrack’s Point, near the site of the garrison, and where the officers’ quarters were erected, now occupied as a residence by Mr. Band, the Bursar of the Reformatory. We camped there in huts made of poles covered with cedar bark. There were only three houses there: a block-house, the quarters of Capt. Woodin, the post-commander; a log-house covered with cedar bark for the sailors near the shore; and a log-house on the hill, called the “Masonic Arms,” a place of entertainment kept by Mrs. Johnson. 5

The town site of Penetanguishene was then mostly a cedar swamp – with a few Indian wigwams and fishing shanties. Beausoleil Island (Prince William Henry Island) was formerly called St. Ignace by the French. A French-Canadian, named Beausoleil, from Drummond Island, settled there in 1819, and it was named afterwards from him. He died at Beausoleil Point, near Penetanguishene. We lived next neighbor to Post Sergeant Rawson, who hauled down the British flag at the garrison when the Government delivered Drummond Island to the Americans. His son William afterwards lived in Coldwater. M. Revolte (Revol), a trader from Drummond Island, built the first house in Penetanguishene, on the lot in front of where the late Alfred Thompson’s residence now stands, and afterwards occupied by Rev. Father Proulx. Gordon, a trader from Drummond Island, built the next on the lot beside it, afterwards occupied by Trudell, who married Miss Kennedy. The house is still standing and occupied by the Misses Gordon, daughters of the original Gordon who settled at Gordon’s Point. (Louie’s account does not coincide with that of the Misses Gordon, who say their father came several years previous to M. Revol and built first, removing from Gordon’s Point, just east of the Barrack’s Point, where he settled in 1825, while the house was still unfinished. During this period Revol built his residence.) Dr. Mitchell, father of Andrew Mitchell, built the next house on the lower corner of the lot, where the Mitchell homestead now stands. It was burned some years ago.

William Simpson married a squaw who had a small store in Drummond Island. Like the rest of the fur-trading class, he, in those days, was given to wandering about the country. He lived among the Drummond Islanders in various capacities, at one time with my father. One day my mother hinted to him that he might marry the squaw with the little store and he would then have a home. “Will you speak to her for me?” said bashful young Simpson. My mother said she would and found it would be quite agreeable, and they were married. This is the way Mr. Simpson got his start in life, and he afterward became a shrewd business man and a rich merchant. 6 They came to Penetanguishene and started a small store. His wife died soon after, and he then married a sister of Joseph Craddock, of Coldwater. His first wife is buried behind the old store, originally log, but now clapboarded and owned by Mr. Davidson. Mr. Simpson built about the same time as Dr. Mitchell, and on the opposite corner eastward.

Andrew Mitchell’s wife was a daughter of Captain Hamilton, of North River. Andrew retired one night in usual health and died suddenly during the night. His widow married his clerk, James Darling, (afterwards Captain Darling). Lieutenant Carson was in command of the 68th Regiment when the forces moved from Drummond Island to Penetanguishene. Sergeant Rawson was barrackmaster, and Mr. Keating was fort adjutant. Lieutenant Ingall of the 15th Regiment, also from Drummond Island, died in Penetanguishene. Mr. Bell, barrackmaster at Drummond Island and Penetanguishene, died at the latter post. His son married a sister of Charles Ermatinger of the North-West Fur Company, who built the stone mansion 7 at the “Sault.”

George Gordon, a Scotch trader from Drummond Island, married a half-breed, settled at Gordon’s Point, a little east of the Barrack’s Point. Squire McDonald of the North-West Company bought from my father the farm where Squire Samuel Fraser now lives. He often called at Drummond Island on business of the company, and came to Penetanguishene with the soldiers. Fathers Crevier and Baudin were the only priests who visited Drummond Island in my recollection. There was another interpreter named Goroitte, a clerk at Drummond Island, who issued marriage licenses. Hippolyte Brissette and Colbert Amyot went with the North-West Company to Red River, Fort Garry and across the Rocky Mountains to Vancouver. Hippolyte was tattooed from head to foot with all sorts of curious figures, and married an Indian woman of the Cree tribe. She was rather clever, and superior to the ordinary Indian women. Francis Dusseaume was also in the North-West Company at Red River, and married a woman of the Wild Rice Tribe. H. Brissette, Samuel Solomon and William Cowan were all with Captain Bayfield in the old Recovery during his survey of the thirty thousand Islands of the Georgian Bay in 1822-25. William Cowan was a half-breed, whose grandfather, a Scotch trader and interpreter, settled at the “Chimnies,” nearly opposite Waubaushene, in the latter part of last century. This man was drowned near Kingston. 8

Hippolyte Brissette was 102 years old when he died. The first St. Ann’s (R.C.) church was built of logs about the time we came here. It was afterwards torn away and rebuilt of frame, which again was replaced by the present memorial church of stone. I remember Bishop McDonnell’s visit to Penetanguishene about 1832. Black Hugh McDonnell, as he was called, was related to the Bishop. The late Alfred Thompson was clerk for Andrew Mitchell, who, with his father, Dr. Mitchell, came from Drummond Island about the time the soldiers came. Highland Point (now Davidson’s Point), was called Lavallee’s Point; the next point east was cal]ed Trudeaux Point, after the blacksmith; the next point east, now called “Wait a Bit,” was named Giroux Point, formerly called Beausoleil Point; next was Mischeau’s Point; next, Corbiere’s Point all named after Drummond Islanders. Louis Lacerte, Joseph Messier, Prisque Legris, Jean Baptiste Legris, Jean Baptiste LeGarde, Pierre LaPlante, all settled on park lots, now known as the Jeffery or Mitchell farm, and all came from Drummond Island. Louis Descheneaux settled on a farm and built the first house at Lafontaine, still standing. Joseph Messier built the next. H. Fortin, Thibault, Quebec, Rondeau and St. Amand, all French-Canadians from Red River and Drummond Island, settled at the old fort on the Wye. Champagne, the carpenter, settled on the lot now owned by Mr. McDonald. John Sylvestre, my brother-in-law, had the contract for building the Indian houses on Beausoleil Island, at the first village. Captain Borland built the others. He was Captain of the Penetanguishene, the first steamer that was built in Penetanguishene. It ran between there and Coldwater. Louis George Labatte, blacksmith, came from Drummond Island after we did. He and his family left Penetanguishene in a bateau to go toward Owen Sound. They were towed by the steamer Penetanguishene with two ropes. A storm came on and one of the ropes broke. His nephew took the rope in his mouth and crawled out on the other rope and hitched it again. It broke the second time and the storm drove them into Thunder Bay (Tiny), where they settled; descendants are still living there. Prisque Legris shot a deserter on Drummond Island, and fell and broke his neck while building a stable for Adjutant Keating in Penetanguishene. People thought that it was sent as a punishment to him. Three French-Canadians- Beaudry, Vasseur and Martin – started for French River and camped over night with an Indian at Pinery Point. They got the Indian drunk, and Vasseur attempted to assault the squaw. Next morning as they started the squaw told her husband. The Indian came down to the shore and shot Vasseur. He was taken to the house of Fagan, Commissary’s clerk at the garrison, where he died in three days.

Once I took a Jesuit priest to Beausoleil Island to look for a Eucharist said to be buried there, with French and Spanish silver coins guns, axes, etc. The spot, he said, was marked by a stone two feet long with a Latin inscription on it. The priest had a map or drawing showing where the stone ought to be, and where to dig, but we found nothing. I knew the hemlock tree and the spot where it was said Father Proulx found the pot of gold, and I saw the hole, but it was made by Indians following up a mink’s burrow. Peter Byrnes, of the “Bay View House,” Penetanguishene, and a friend spent a day digging near an elm tree not far from the same spot, near the old Fort on the Wye. Sergeant James Maloney, of the militia, found two silver crosses on Vent’s farm, near Hogg River. Many pits have been dug on Beausoleil Island, Present Island, Flat Point and other places in search of hidden treasures. An Indian and myself once found a rock rich with gold near Moon River. We marked the spot, but I never could find it on going back. My chum would never go back with me, for he said, “Indian dies if he shows white man treasure.” I found red and black pipe-stone images at Manitoulin, brought from the Mississippi River by the Indians. I was once asked by Dr. Taché to go with him to the supposed site of Ihonatiria, at Colborne Bay or North-West basin, across Penetanguishene Harbour, and J. B. Trudeaux also went. I told him of the spot on the creek where they would find relics. They spent some time in digging and found pieces of pottery, clay pipes, etc.

Once I conducted the Earl of Northumberland through the Indian trail from Colborne Bay (North-West Basin) to Thunder Bay and back in one day, and we got twenty five dollars for my services (Antoine Labatte says the distance by this trail was seven miles). I was the first man to pilot the steamer Dutchess of Kalloola to the “Sault.” I got four dollars per day for this service. She was built at Owen Sound, I think. I also piloted the Sailor’s Bride into Port Severn, the first vessel that ever entered there. She was loaded with lumber at Jenning’s mill. I was guide for Captain West and David Mitchell (a young man from Montreal) to Manitoulin on snowshoes. I had three assistants – Aleck McKay, Pierre Laronde and Joseph Leramonda, half-breeds. I received one hundred dollars for the trip. Captain West was an extensive shipowner in England, on a visit to his brother, Col. Osborne West, commandant of the 84th Regt. stationed here. I was guide for Col. W. H. Robinson, son of Chief-Justice Robinson, to Manitoulin, also Bishop Strachan and his son, Capt. James Strachan, to Manitoulin and the “Sault,” and various other notables at different times. I went with Captain Strachan for two summers to fish for salmon; also for three seasons to Baldoon, on the St. Clair flats, to shoot ducks. My father once owned the land where Waubaushene now stands. Indians always call it “Baushene.” The garrison once owned a big iron canoe, curved up high at each end just like a birch-bark canoe. It was built by Toussaint Boucher on the spot where Dr. Spohn’s house now stands. The pattern was cut out by an Indian named Taw-ga-wah-ne-gha. It carried fourteen paddlers and six passengers, besides the usual attendants, with provisions and supplies, and was about forty-five feet long. I made several excursions up Lake Huron in it. It was rigged for sailing, but was no good in a storm, as it cut through the waves and was in danger of filling, while the bark canoe bounded over them.

I remember Colonel Jarvis, Colonel Sparks, Captain Buchanan, Captain Freer, Captain Baker, Lord “Morfit ” 9 (Morpeth), Lord Lennox, Master George Head{ 10 (a boy about fourteen years of age), the son of Sir Francis Bond Head, Mr. Lindsay and several gentlemen, starting for a trip to Manitoulin and the “Sault” accompanied by my father as interpreter, myself and fifty-six French voyageurs from Penetanguishene. Two of the birch-bark canoes were about twenty feet long, while the iron canoe and one bark canoe were of equal length. 11 Each canoe had its complement of paddlers and passengers in addition to provisions and supplies. On arriving at Manitoulin we held a grand “pow-wow” with the Indians and distributed the annual presents, after which the party started for the North Shore (having previously visited the Hudson’s Bay Co.’s post at French River), Killarney, and other points onward to the Sault. While at the “Sault”, Lord Morpeth, Lord Lennox and party stopped at the big stone mansion built by Charles Ermatinger a long time ago. From the “Sault” we started for Detroit, calling at Drummond Island, Mackinaw, Bay City, Saginaw, Sable River, Sarnia and other points on the way. I was attendant on Lord Morpeth and Lord Lennox. I was obliged to look after their tents, keep things in order and attend to their calls. Each had a separate tent. My first salute in the morning would be, “Louie, are you there? Bring me my cocktail.” – soon to be followed by the same call from each of the other tents in rotation, and my first duty was always to prepare their morning bitters.

While camped near the Hudson’s Bay post at French River Lord Morpeth went in bathing and got beyond his depth and came near drowning. I happened to pass near, and reached him just as he was sinking for the last time, and got him to a safe place, but I was so nearly exhausted myself that I could not get him on shore. Mr. Jarvis came to his lordship’s assistance and helped him on to the rock. Lord Morpeth expressed his gratitude to me and thanked me kindly, saying he would remember me. I thought I would get some office or title, but I never heard anything further about it. Mr. Jarvis afterwards got to be colonel, and I suspect he got the reward that should have been mine by merit.

On passing Sarnia we had a narrow escape from being shot at and sunk to the bottom. It was dark as we got near, and the sentinel, Mr Barlow, demanded the countersign. Colonel Jarvis refused to answer or allow any other person to do so. The guard gave the second and third, challenge, declaring, at the same time, that if we did not answer be would be compelled to fire. Still Mr. Jarvis would not answer for some unexplained reason, when my brother Ezekiel, called out, contrary to orders, and saved the party. Upon landing Mr. Jarvis was informed by the sentinel that be had barely saved himself and the party from a raking fire of grape-shot, and wanted to know what he meant by risking the lives of the whole fleet of canoes, but Mr. Jarvis made no reply. 12

When we arrived at Detroit two of the birch-bark canoes were sent back, and Lord Morpeth, Lord Lennox and myself boarded the steamer for Buffalo. There they took the train for New York, intending to sail for England. They wanted me to go to England with them but I refused. When Lord Morpeth asked me what he should pay me for my attendance I said, “Whatever you like, I leave that to yourself.” “Ha! ha!” said he, with a twinkle in his eye, “What if I choose to give you nothing?” He gave me the handsome sum of two hundred dollars, besides a present of ten dollars in change on the way down, which I was keeping in trust for him. Lord Lennox sailed from New York ahead of the others, and was never heard of after. The vessel was supposed to have been lost, with all on board. I left them at Buffalo and went back to Malden, where I met my fellow voyageurs, and we came down Lake Erie, making a portage at Long Point. We came up the Grand River, crossed to the Welland Canal and down to St. Catharines. We got two wagons here and portaged the canoes down to Lake Ontario, as the canal was too slow. We went round the head of the lake to Hamilton, and so on to Toronto, where they gave us a grand reception. We left the canoes in Toronto, and the “iron canoe” was brought up the next year. It was hauled over the Yonge Street portage on rollers with teams to Holland Landing and taken up Lake Simcoe to Orillia, through Lake Couchiching, down the Severn River to Matchedash Bay, and home to Penetanguishene.

Neddy McDonald, the old mail-carrier, sometimes went with us, but he was not a good paddler, and we did not care to have him. It is said that it fell to Neddy’s lot, on the trip with Lady Jameson, to carry her on his back from the canoe to the shore occasionally when a good landing was not found. As Mrs. Jameson was of goodly proportions, it naturally became a source of irritation to Neddy, which he did not conceal from his fellow voyageurs. Mrs. Jameson had joined the party of Colonel Jarvis at the Manitoulin Island. She was a rich lady from England, well educated, and traveling for pleasure. She was an agreeable woman, considerate of others and extremely kind-hearted. I was a pretty fair singer in those days, and she often asked me to sing those beautiful songs of the French voyageurs, which she seemed to think so nice and I often sang them for her. Mrs. Jameson ran the “Sault Rapids” in a birch-bark canoe, with two Chippewa Indian guides. They named her Was-sa-je-wun-e-qua, 13 “Woman of the bright stream.”

I was attendant on Mrs. Jameson, and was obliged to sleep in her tent, as a sort of protector, in a compartment separated by a hanging screen. I was obliged to wait till she retired, and then crawl in quietly without waking her. Mrs. Jameson gathered several human skulls at Head Island, above Nascoutiong, to take home with her. She kept them till I persuaded her to throw them out, as I did not fancy their company. When I parted with Mrs. Jameson and shook hands with her I found four five dollar gold pieces in my hand.

We lived near the shore just past the Barrack’s Point while my father was in the Government service at Penetanguishene, and where my mother died. After he retired we moved into town, near Mrs. Columbus, where he died. Col. Osborne West, commandant of the 84th Regiment, stationed at the garrison, cleared the old cricket ground, and was a great man for sports. My mother was buried with military honors. Captain Hays, with a detachment of the 93rd Highlanders, Colonel Sparks, the officers of the Commissariat, Sergeant Major Hall, Sergeant Brown, the naval officers and the leading gentry of the garrison, besides many others, formed the escort to St. Anne’s cemetery, where she was buried. My father’s remains were buried beside hers, and the new St. Anne’s Church was built farther to the west and partly over their graves.

Stephen Jeffery owned a sailing vessel which he brought from Kingston, and in which he brought the stone from Quarry Island to build the barracks. He kept the first canteen on the spot now occupied by the Reformatory, just above the barracks, and built the old “Globe Hotel” where the “Georgian Bay House” now stands. He felled trees across the road leading to Mundy’s canteen, on the old Military Road, so as to compel customers to come to the “Globe” tavern and patronize him. He afterwards built the “Canada House.” Keightly kept the canteen for the soldiers at the garrison, and then a man named Armour.

Tom Landrigan kept a canteen, and bought goods and naval supplies stolen by soldiers from the old Red Store. He was found guilty with the others, and sentenced to be hung. It cost my father a large sum of money to get Tom clear. He was married to my sister.

One day I went up to the cricket ground and saw something round rolled in a handkerchief, which was lying in the snow, and which the foxes had been playing with. When I unrolled it, the ghastly features of a man looked up at me. It was such a horrible sight that I started home on the run and told my father. He went up to investigate, and found it was the head of a drunken soldier, who had cut his throat while in delirium tremens at Mundy’s canteen, and had been buried near the cricket ground. Dr. Nevison, surgeon of the 15th Regiment, had said in a joke, in the hearing of two soldiers; that he would like to have the soldier’s head. They got it, presented it to him, when he refused it, horrified. They took it back and threw it on the ground, instead of burying it with the body, and it was kicked about in the way I mention for some time. One of the two soldiers afterwards went insane, and the other cut his thumb and died of blood-poisoning in Toronto. The names of the two soldiers were Tom Taylor and John Miller.

I remember seeing a big cannon and several anchors standing near old Red Store, the depot of naval supplies, but I don’t know what became of them. I remember the sale of the old gun-boats at public auction by the Government, together with the naval stores and military supplies. One of the old gunboats sunk in the harbor, the Tecumseth, nearest the old naval depot, is said to have a cannon in her hold. I knew Capt. T. G. Anderson, Indian Agent and Customs Officer at Manitoulin Island. The 84th Regiment, Col. Osborne West, Commandant, was the last regiment stationed at Penetanguishene. Captain Yates, in the same regiment, was dissipated and got into debt. He was obliged to sell his commission, and finally left for Toronto. St. Onge dit La Tard, Chevrette, Boyer, Coté, Cadieux, Desaulniers, Lacourse, Lepine, Lacroix, Rushloe (Rochelieu or Richelieu ?), Precourt, Desmaisons and Fleury, a Spaniard, all came from Drummond Island. Altogether (in Louie’s opinion) about one hundred families came.

Citations:

- Ezekiel Solomon, the grandfather of Lewis, was a civilian trader at Michilimackinac when the massacre of June 4th, 1763, took place. (See Alex. Henry’s Journal.) He was taken prisoner, but was rescued by Ottawa Indians, and later on was ransomed at Montreal.[

]

- She was a daughter of John Johnston, whose “Account of Lake Superior, 1792-1807,” may be found in Masson’s “Bourgeois” (Vol II). Henry R. Schoolcraft, the noted scholar of the Indian tribes, and Rev. Mr. McMurray also married daughters of Mr. Johnston; and both of these gentlemen were accordingly uncles, by marriage, of our narrator, Louie Solomon.[

]

- Probably Assumption College, or the school which was its prototype, at Sandwich, Ontario, rather than a school at L’Assomption, Quebec.[

]

- The variations in the spelling of this name are legion. Here are a few of them: Deshommes, Dusome, Deschamps, and Jussome.[

]

- This is the famous hostelry where Sir John Franklin was entertained in 1825 on his way north, John Galt in 1827, as also the Duke of Richmond, Lord Sydenham, Lord Lennox, Lord Morpeth, Lord Prudhomme, Capt. John Ross, R. N., Sir Henry Harte, and several other men of note.[

]

- William Simpson represented the townships of Tiny and Tay in the Home District Council at Toronto for the year 1842.[

]

- This mansion was built about the time of Lord Selkirk’s visit to Canada in 1816-18. It is still standing, and has many interesting family associations.[

]

- This probably refers to the interpreter Cowan, who was lost in the schooner Speedy near Brighton in 1805. It was at his place the “Chimneys”, where Governor Simcoe stayed on his way to visit Penetanguishene Harbor in 1793.[

]

- Lord Morpeth, the seventh Earl of Carlisle, made this trip in 1842. In a pamphlet, a copy of which is preserved in the Toronto Public Library, giving his “Lecture on Travels in America,” delivered to the Leeds Mechanics’ Institution and Literary Society, Dec. 6th, 1850, he says (p. 40): “I was one of a party which at that time went annually up the lake to attend an encampment of many thousand Indians, and make a distribution of presents among them. About sunset our flotilla of seven canoes, manned well by Indian and French-Canadian crews, drew up, some of the rowers cheering the end of the day’s work with snatches of a Canadian boat-song. We disembarked on some rocky islet which, as probably as not, had never felt the feet of man before; in a few moments the utter solitude had become a scene of bustle and business, carried on by the sudden population of some sixty souls.” He then describes the camp scenes at greater length.[

]

- As Mrs. Jameson says Master Head was one of the party with her in 1837, he was probably not in this party with Lord Morpeth. It is likely the narrator’s memory has failed him in regard to the exact party which Master Head accompanied, and this is not surprising, as Louie went with so many expeditions.[

]

- Louie’s idea of dimensions is evidently astray. Competent authorities say the “Iron Canoe,” was about twenty-four feet in length, and capable of carrying twenty barrels of flour; as to birch-bark canoes, I have seen one that was said to have carried sixty men, and was capable of carrying fifty barrels of flour.[

]

- This is in marked contrast with the frankness of Lord Morpeth on another occasion, which Louis fails to relate, but which was told by another of the voyageurs. One day while duck-shooting Lord Morpeth brought down a duck, at the same time peppering his companions so that they bled profusely, Mr. Jarvis among the rest. In a stern voice, manifesting a fair show of rage, Mr. Jarvis shouted “Lord Morpeth, what do you mean? You have shot the whole party!” The reply came prompt, but frank, “I don’t care a damn I’ve killed the duck anyhow.”[

]

- This name is spelled Wah-sah-ge-wah-no-qua by Mrs. Jameson in “Winter Studies and Summer Rambles,” vol 3, p. 200. She gives its meaning as “Woman of the bright foam,” and says it was given her in compliment of her successful exploit of running the rapid.[

]