A short calm followed the battle of Tippecanoe. But the influence of the British trading agents and emissaries was not wanting to awaken Indian hostility, and that of the ever active Tecumseh was at work among the Indians, and their hatred of the whites only needed such a man to make it break forth into open hostility. Another event precipitated that which Tecumseh desired. War was declared by the United States against Great Britain, on the 18th of June, 1812. Of course the Indians took advantage of this state of things, and commenced their horrible ravages at once. The whole western frontier was attacked at various times, and the most dreadful cruelties were everywhere perpetrated. Many of the inhabitants deserted their homes and sought safety in flight. The series of battles which took place in 1812 and 1813 in the northwest are called the Northwest Territorial War of 1812.

A large number of the Indians joined the British forces sent into Canada and Michigan, and the inactivity of the United States’ troops under General Hull, contributed to swell their number and spirit. A detachment of two hundred men under Major Vanhorne, fell into an ambush of a much inferior force of British and Indians, and was defeated with considerable loss. Soon after, Colonel Miller, with about six hundred men, routed a large force of British and Indians near Maguaga village. The Indians were commanded by Tecumseh, and fought more bravely than their allies. The enemy’s loss was about seventy men killed and wounded. The loss of the Americans was nearly as great. This victory, however brilliantly won, produced no beneficial result.

The force which besieged Detroit consisted of thirteen hundred British and Indians, under General Brock. On the approach of the enemy, the women, and children, and old men, left the place and took shelter in a neighboring ravine where they remained several days in terrible suspense awaiting the result.

The Americans in Detroit were fully capable of repulsing the British force, and were but waiting the onset to display their valor, when their pusillanimous general surrendered to the enemy without striking a blow. After such an instance of imbecility on the part of General Hull, the Indians became bolder than ever, and their ravages of the American settlements were constant.

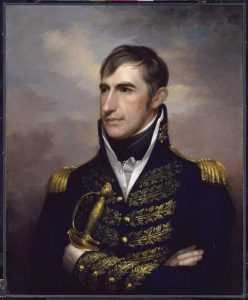

The people of the west made great exertions to place a force in the field capable of retrieving the disgrace of the American arms, and of protecting their lives and property. Kentucky, especially, raised a large body of her hardy sons. By the unanimous call of the people, William Henry Harrison was appointed major-general, and commander-in-chief of the army of the west. His known abilities and his great experience made him the favorite of all. General Harrison immediately prepared for vigorous service.

He arrived at Cincinnati on the 28th of August, and on the following day put the troops in motion. On the 1st of September, the army reached Dayton; and, on the 3d, arrived at Pique, a small village on the west bank of the Great Miami. Here, having learned that the Indians had invested Fort Wayne, he dispatched Colonel Allen with about five hundred men, directing him to make forced marches for its relief. A regiment of seven hundred mounted men, under Colonel Adams, was on its way from Ohio, for a similar purpose. The whole army was put in motion for the same place, on the 6th; and, on the 8th, overtook Colonel Allen’s command, at St. Mary’s River, where also it was joined, on the same day, by Major R. M. Johnson, with a corps of mounted volunteers. General Harrison’s force now amounted to about two thousand two hundred men.

Fort Wayne is situated on the little river, at its junction with the St. Joseph’s. Being in a favorable situation to communicate with Detroit and the Rapids, it was to be expected that the enemy would attempt it. It had accordingly been invested for several days by the Indians, who resorted to various artifices to obtain possession. The garrison, however, which consisted of but seventy men, maintained their post with great bravery. The besiegers, who had obtained information of the approach of the American force, decamped precipitately on the evening preceding its arrival, having previously burnt the little village in the vicinity of the fort, and the factory which had been erected by the government to supply them with farming utensils.

The army arrived at Fort Wayne on the 12th; and, on the succeeding day, it was determined, in a council of officers, to divide it into two parts, for the purpose of laying waste the Indian settlements. The first division was composed of the regiments of Lewis and Allen, and a troop of horse, under Captain Garrard, and was commanded by General Payne, who was accompanied by General Harrison. It left the camp on the 14th, with a view to destroy the Miami villages, at the forks of the Wabash. On the 15th, the expedition arrived at the place of destination, which they found abandoned by the Indians. They encamped in the town, and having destroyed its buildings, and cut up the corn, returned on the 18th to the fort, without having lost a man, or seen an enemy.

The second division was commanded by Colonel Wells, and consisted of part of his own regiment, with that of Scott, and some mounted men, and was directed to destroy the Potawatomie village on the Elkhart River; which service it completely effected, obtaining a considerable quantity of provision and forage. They rejoined the main body, a few hours after the arrival of the first expedition.

On the day succeeding the concentration of these divisions at Fort Wayne, brigadier General James Winchester arrived, and took command of the army. He, too, had served in the war of the revolution; but, being personally a stranger to the troops, and an officer of the regular army, his arrival seems to have produced considerable uneasiness and discontent, which it required all the influence of General Harrison to assuage. The latter, being now superseded in his command, left the fort, for the purpose of organizing and bringing up the forces in the rear.

General Winchester now moved forward his army, with a view of occupying Fort Defiance, at the mouth of the river Auglaize, and there awaiting the arrival of the reinforcements from Kentucky and Ohio. The country, through which he was obliged to pass, presented difficulties of no ordinary nature, by reason of the almost impenetrable thickets and marshes, with which it is covered. The progress of the army was, therefore, very slow, seldom exceeding five or six miles in twenty-four hours. From the apprehensions entertained of an attack by the Indians, it became necessary to fortify the camp every night; and the march of the army was always preceded by a reconnoitering party of spies. On the 25th, ensign Liggett, of the advanced party, obtained permission to proceed, with four volunteers, for the purpose of discovering the strength of the enemy at Fort Defiance. Late on the same evening, they were attacked by a party of Indians, and, after defending themselves with great valor, were overpowered, and the whole party put to death. Subsequent to this affair, various skirmishes took place between the spies in advance and the Indian forces, which had the effect of impeding the march of the army, and harassing the men. The Indians appear to have been the advanced party of an army destined to attack Fort Wayne, which consisted of two hundred regulars, with four pieces of artillery, and about one thousand Indians, the whole under the command of Major Muir. The intelligence, however, of the approach of the force under Winchester, the numbers of which were considerably exaggerated, and the report of an additional body being on the Auglaize, caused an abandonment of the project, and a retreat down the Miami. General Winchester, however, who was ignorant of the motions of his enemy, proceeded with great caution, fortifying his camp, as usual, at night, and sending reconnoitering parties in all directions. The army had now begun to suffer severely from a want of provisions, Colonel Jennings, who had been dispatched by General Harrison, down the Auglaize with a supply, not being able to reach Fort Defiance, from the presence of the enemy. An escort was, therefore, sent forward by General Winchester: and after great difficulty and labor, the supplies were conveyed to the army, on pack horses. An express had, in the meantime, been dispatched to General Harrison, acquainting him with the situation of the troops, and the force of the enemy, and, the 30th of September, the army took possession of Fort Defiance, from which the enemy had previously retreated.

In the meantime, General Harrison had been forming the remainder of the Kentucky draft, and some riflemen and volunteers, from Ohio, into an army, with which he appears to have contemplated making a coup-de-main on Detroit, by taking an unfrequented route. These troops had been detained a long time at the places of rendezvous, by the want of some of the material munitions of war. They had, however, assembled at the river St. Mary’s, on the 20th of September. On the 24th of that month, General Harrison received, from the war department, information of his appointment to the command of the 8th military district, including the northwestern army, the commission of Brigadier in the regular army having been previously conferred upon him.

With this appointment extensive power was conferred and equally extensive and arduous services were required. He was directed to provide for the security of the western frontier; to take Detroit, and to penetrate as far into Upper Canada as his force would justify. From the number and scattered situations of the posts and settlements on the frontier, and the roving bands of Indians ready to assail them, it is evident, that the task of protecting them, and, at the same time, prosecuting offensive operations, in other quarters, required great skill and activity. The force, throughout his district, of all descriptions, was estimated at ten thousand men; of which, about two thousand were with General Winchester, and nearly three thousand at St. Mary’s, under his personal command.

Harrison immediately formed the plan of the campaign. The rapids of the Miami was the first object, and the attack was to be made in three divisions. While arranging his plans, Harrison received intelligence of the supposed critical situation of General Winchester’s force, and marched to his assistance; but the retreat of the enemy, left him at liberty to pursue his own arrangements. One thousand mounted men, under General Tupper, was sent to disperse the Indians collected at the Rapids, but the expedition failed, on account of the insubordination of the troops, and the want of energy in the commander.

While these events were occurring in the neighborhood of Lake Erie, others of importance took place on the western frontier. Of these, the first in point of time, and one most worthy of notice was the brave defense of Fort Harrison. This post, which was situated on the river Wabash, in the Indiana territory, was garrisoned by about fifty men, one-third of whom were sick, under Captain Zachary Taylor, of the regular army.

On the evening of the 3d of September, two young men were shot and scalped, in the vicinity of the fort; and, on the succeeding night, the attack was commenced by the conflagration of a block house, in which the provisions were contained; and at the same time a brisk fire was opened by a large body of the Indians, who had lain in ambush. The fire was returned with great spirit by the garrison; and, as the destruction of the block house had caused an opening in his line of defense, Captain Taylor, with great presence of mind, pulled down a cabin, and with its materials constructed a breastwork across the aperture. The situation of this small but gallant party became, however, very critical, as the attempts of the enemy to enter by the breach produced by the fire, were of a most desperate nature. Two of the garrison, preferring the risk of capture by the enemy to the prospect of massacre in the fort, endeavored to make their escape. One of them was immediately killed; the other returned to the walls, and remained concealed until morning. The enemy, finding their attempts to gain possession ineffectual, retreated about day-light, but remained in the vicinity of the fort for several days. Their loss was supposed to have been considerable; that of the garrison was only three killed and three wounded: but the destruction of the block house was a serious disadvantage, as it contained the whole of the provisions. For his gallant conduct on this occasion, Captain Taylor was shortly after brevetted a major.

In the middle of November, a large force of Kentuckians, under General Hopkins, proceeded into the Indian country, and destroyed the Prophet’s town and a Winnebago village. The inclemency of the weather, and the constant retreat of the Indians rendered pursuit useless, and inconvenient, and the detachment accordingly returned to Vincennes. Another detachment, consisting of three hundred regulars, under Colonel Russel, surprised and destroyed an Indian town on the Illinois River, and after driving the inhabitants into a swamp, captured twenty of them. Several other expeditions were undertaken, in which the Indians felt the full power of the revengeful inhabitants of the western towns. A body of six hundred men, under Colonel Campbell, marched against the towns of the Mississenawa. A large number of Indians were captured or killed, but the Americans lost forty men in a subsequent attack by the Indians.

In the battle of Frenchtown, on the 17th of January, 1813, about four hundred Indians were engaged, and fought bravely; but they were defeated, with considerable loss by the Americans, under Colonel Lewis. Soon after, General Winchester arrived with his whole force, and it was intended that the army should commence the arrangements of a fortified camp on the 22d. But a more serious labor awaited them, and many were doomed to meet a terrible fate before that time.

Late in the evening of the 21st, information was given to General Winchester, by a person who had recently left Malden, that a large force of British and Indians was about to march from that place, shortly after his departure. Unfortunately, however, little attention appears to have been given to the report: and the most fatal security prevailed among both officers and men, unsuspicious of the tragedy about to follow.

A most striking proof of the want of proper preparation on the part of the American commander is evinced by the fact, that no picket guard was placed at night, on the road by which the enemy was to be expected. The latter had thus been enabled to approach very near to the camp without discovery, and to station their cannon behind a small ravine, which ran across the open fields on the right. Soon after daylight, on the 22d, they opened a heavy fire from their artillery, at the distance of three hundred yards. The American troops were immediately formed, and received a charge from the British regulars, and a general fire of small arms. The detachment under Colonel Lewis, being defended by pickets, soon repulsed the enemy: but the reinforcement which had arrived with General Winchester were over-powered; and not being able to rally behind a fence, as directed by the general, were thrown into complete confusion, and retreated in disorder across the river. All attempts to rally this unfortunate body, although made in various places by General Winchester and Colonels Lewis and Allen, proved in vain. They endeavored, as the Indians had gained their loft flank and rear, to make their escape through a long lane, on both sides of which the Indians were stationed, by whom they were shot down in every direction. Their officers also, carried in this general tide of flight, attempted to escape, only in most instances, to be massacred. Colonel Allen, and Captains Simpson and Mead, were killed on the field, or in the flight: and General Winchester, with Colonel Lewis, were captured a short distance from the village.

That part of the American force, however, which had been stationed behind the picketing, maintained their post with undiminished bravery. About ten o’clock, the British commander drew off his forces, with the apparent intention of abandoning the conflict: but, finding that General Winchester was his prisoner, he represented to him, that nothing but an immediate surrender could save the rest of the Americans from massacre by the Indians. Influenced by this appeal, the general consented to issue the order, which was conveyed to the detachment by a flag of truce. Finding that the force opposed to them was far superior in numbers, that there was no possibility of a retreat, and that their ammunition was nearly exhausted, Major Madison, who commanded, consented to surrender, on condition of being protected by a guard, and that the sick and wounded should be sent, on the succeeding morning, to Amherstburg. Colonel Proctor, the British commander, having promised the American officers, that their wounded should be removed the succeeding day, marched, about twelve o’clock, with his prisoners, leaving Major Reynolds, with two or three interpreters.

The Frenchtown Massacre

The unfortunate soldiers, who had been thus left, wounded and helpless, in the power of their enemy, had a right to expect, that, at least, the common duties of humanity would be exercised towards them. But the most horrid act of this sanguinary tragedy was yet to be performed. Charity induces us to hope, that the tales which innumerable eye-witnesses and sufferers have related of the barbarities that ensued, have been heightened by the coloring with which it was natural to invest them. Making all due allowance, however, on this ground, enough remains to satisfy the mind, that the cruelties perpetrated, on this occasion, were as shocking to human nature, as any which history, fruitful as it is of the crimes of man, has ever recorded. For the slaughter that has sometimes followed a desperate and protracted resistance, some apology may be found in the exasperated passions of our nature. Self-defense, too, may require, and humanity may then palliate, the destruction of prisoners: but for the massacre of the wounded, no excuse of this sort can be devised. Their sufferings speak a language which none of the children of a common God can misunderstand, and which the greater part of mankind have therefore respected. The result of this affair affords a strong admonition against the employment, in civilized warfare, of allies by whom the most sacred calls of humanity are habitually disregarded. To the immediate agents of this sanguinary outrage, the scene was not new: their Indian habits, and equally barbarous religion, as well as their ancient hostility to the whites, threw no impediments in the way of the gratification of their revenge. But no excuse of this nature can be offered on the part of the British commander. It had been often said by the friends of Great Britain that the ties by which a common language, a common religion, and a common descent, bound the two nations together, were of the strongest and most endearing kind. These claims upon the humanity of their enemy unfortunately availed nothing to the sufferers at Frenchtown: their blood, which flowed so profusely, affords a striking proof of the feebleness of the moral bonds by which nations are connected, as well as of the inconsistency which often exists between the faith and the actions of a people. The speculative philanthropy of the British nation has led it to disseminate in every quarter of the globe the doctrines of a pacific religion, and the precepts of a pure morality: but the remembrance of the tears and bloodshed of Frenchtown, will long darken its fame, and foster a spirit of animosity towards it, in a people whom Providence has destined to survive both its charities and its cruelties.

It has been said that the British officers were not responsible for the deeds of their allies, who acted upon no suggestion or impulse but their own. Admitting the fact, that no influence was exerted over them, the moral offense of their Christian coadjutors is but little diminished. He who, possessing the means of preventing crime, shall yet refuse to interfere, is hardly less guilty than the perpetrator. Posterity, in whose impartial scales these awful scenes are to be weighed, will not hesitate to include in the same sentence of condemnation by those who committed the massacre, and those by whom it was not forbidden. 1

The Indian warriors, who had participated in the engagement, had chiefly left the village of Frenchtown, with their allies, soon after the conclusion of the conflict. They proceeded, however, only a few miles on the road to Malden; and at sunrise, on the succeeding day, returned to the village. The miserable night, which succeeded the battle, had been passed by the wounded in a state of anxious suspense, suffering from their corporeal calamities, and uncertain of the fate which awaited them. With the return of day, however, came a renewal of the hope, that the engagement of the British commander, to provide carriages for their conveyance to Malden, would not be broken. The delusion was of short continuance; the work of death had already begun. Captain Hickman, who lay severely wounded, was dragged to the door, and speedily tomahawked. This was the signal for a general destruction. The houses, in which the greater part of the prisoners were confined, were set on fire, and most of those ill-fated men perished in the conflagration. Those who possessed sufficient strength, endeavored in vain to escape; as fast as they appeared at the windows, they were thrust back into the devouring flames. Others met their death in the streets from the tomahawk, and were left mangled on the highway.

The circumstances attending the destruction of Captain Hart, inspector-general of the army, were peculiarly melancholy, and reflect the greatest disgrace on those who ought to have prevented it. Being severely wounded, previous to the departure of the enemy, he expressed to Captain Elliott, of the British army, with whom he had been personally intimate, a desire to be conveyed, with the other prisoners, to Malden. He was assured, however, by the latter, that no danger need be apprehended, and that a conveyance would be provided for him on the succeeding morning: but that morning only arrived to show him the fallacy of the hope of relief, and the fate for which he was reserved. When the Indians arrived at the house in which he was confined, he was attended by a surgeon, who was tied, and conveyed to a British camp, some miles distant. He there met with Captain Elliott, to whom he related the dreadful scenes he had witnessed, and in particular described the impending fate of Captain Hart. The feelings of the British officer were, however, untouched by the narration: and no entreaties could induce him to take means for the preservation of the suffering Americans. The unfortunate Captain Hart had, in the mean time, been able to induce one of the Indians, by the offer of a large pecuniary reward, to convey him to Malden. He was placed on a horse, and was conducted through the vicinity of the town, where they encountered another Indian, who claimed him as his prisoner. To put an end to the dispute, they dragged him from his horse, and dispatched him with a war club. He met his fate with composure and fortitude.

Many other officers are also enumerated among the victims of this dreadful day. Among them were Majors Graves and Woolfolk, the latter an aid of General Winchester.

With further details of individual suffering, it is needless to swell these pages. Of the extent of the massacre, some idea may be formed by the statement, that of the whole American force, previous to the engagement, only thirty-three escaped to the Rapids. Five hundred and forty-seven were taken prisoners by the British, and forty-five by the Indians. Two hundred and ninety were killed during the battle, or put to death subsequently, or were missing, and not afterwards heard of. The slaughter did not cease on that day; for some period afterwards fresh scalps were carried into Malden. The prisoners who had been taken by the British, after being exposed to all the rigor of the inclement season, were marched through the interior to Fort George, where they were paroled, and permitted to return home, by the way of Pittsburg.

The Attack on Fort Meigs

This horrible transaction roused the people of Kentucky to new exertion. Such a massacre might have intimidated those of less spirit. But revenge was now the uppermost thought of the Kentuckians. The plan of operations for the campaign was totally destroyed by this disaster, and General Harrison, with about seventeen hundred men, turned his attention to fortifying his position at the Rapids. The camp was about twenty-five hundred yards in circumference, the whole of which, with the exception of several intervals left for batteries and block houses, was to be picketed with timber fifteen feet long, from ten to twelve inches in diameter, and set three feet in the ground. The position thus fortified was named Fort Meigs. The number of troops in the garrison was afterwards reduced to about twelve hundred by the discharge of those whose time of service had expired.

Small parties of the enemy had been seen at various times, hovering round the camp: and, on the 28th of April, the whole force, composed of British and Indians, was discovered approaching, within a few miles of the fort, and as soon as their ordnance was landed, it was completely invested. The ground in its vicinity had been covered by a forest, which was cleared to a distance of about three hundred yards from the lines. From behind the stumps of the trees, however, which remained, the Indians kept up a severe fire, by which some execution was occasionally done. On the 1st of May, the British batteries being completed, a heavy cannonading commenced, which was continued till late at night. The intervening time had not been spent in idleness by the garrison under the direction of Captain Wood. A grand traverse, twelve feet high, upon a base of twenty feet, and three hundred yards long, had been completed, which concealed and protected the whole army. The fire of the enemy, therefore, produced little effect, except the death of Major Stoddard, of the regular army, an officer of great merit. Disappointed in his first plan of attack, Colonel Proctor transferred his guns to the opposite side of the river, and opened a fire upon the center and flanks of the camp. The cannonading of the enemy continued, for several days, incessant and powerful; that of the Americans, however, produced greater execution; but a scarcity of ammunition compelled them to economies their fire.

In the mean time, a reinforcement of twelve hundred Kentuckians, under General Clay, was descending the river, with the hope of being able to penetrate into the fort. As soon as General Harrison heard of their approach, he determined to make a sally against the enemy on his arrival; and sent an officer, with directions to General Clay, to land about eight hundred men, from his brigade, about a mile above the camp. They were then directed to storm the British batteries on the left bank, to spike the cannon, and cross to the fort. The remainder of the men were to land on the right side, and fight their way into the camp, through the Indians. During this operation, General Harrison intended to send a party from the fort, to destroy the batteries on the south side.

In conformity with this direction, a body of men under Colonel Dudley, were landed in good order, at the place of destination. They were divided into three columns, when within half a mile of the British batteries, which it was intended to surround. Unfortunately, no orders appear to have been given by the commanding officer, and the utmost latitude was, in consequence, taken by the troops. The left column being in advance, rushed upon the batteries, and carried them without opposition, there being only a few artillerymen on the spot. Instead, however, of spiking the cannon, or destroying the carriages, the whole body either loitered in fatal security in the neighborhood, or, with their colonel, were engaged in an irregular and imprudent contest with a small party of Indians. The orders and entreaties of General Harrison were in vain: and the consequences were such as might have been foreseen, had the commanding officer possessed the slightest portion of military knowledge. The fugitive artillerists returned, with a reinforcement from the British camp, which was two miles below. A retreat was commenced, in disorder, by the Americans, most of whom were captured by the British or Indians, or were killed in the pursuit. Among the latter was Colonel Dudley. About two hundred escaped into the fort: and thus this respectable body of men, who, if properly disciplined and commanded, might have defeated the operations of the enemy, became the victims of their own imprudence.

The remainder of General Clay’s command were not much more successful. Their landing was impeded by the Indians, whom they routed, and, with their characteristic impetuosity, pursued to too great a distance. General Harrison perceiving a large force of the enemy advancing sent to recall the victors from the pursuit. The retreat was, however, not affected without considerable loss, the Indians having rallied, and, in turn, pursued them for some distance. The sortie, however, made by a detachment under Colonel Miller, of the regulars, gained for those who participated in it, much more reputation. The party, consisting of about three hundred and fifty men, advanced to the British batteries with the most determined bravery, and succeeded in spiking the cannon, driving back their opponents, who were supposed to be double in number, and capturing forty prisoners. The enemy suffered severely; but rallied, and pressed upon the detachment, until it reached the breastwork. The attempt to raise the siege was thus defeated, from the imprudence and insubordination of the troops concerned, rather than from any original defect in the plan. Many valuable lives were lost during the heat of the battle: and the cruelties perpetrated upon the prisoners, in presence of the officers of the British army, are said to have been little inferior in atrocity to those of the bloody day of Frenchtown.

From this period until the 9th, little of importance occurred. The British commander, finding he could make no impression upon the fort with his batteries, and being deserted, in a great measure, by his Indian allies, who became weary of the length of the siege, resolved upon a retreat. After several days’ preparation, his whole force was accordingly embarked on the 9th, and was soon out of sight of the garrison, with little molestation on their part.

The British and Indians engaged in the siege of Fort Meigs numbered more than two thousand men, led by Proctor and Tecumseh. This was a force sufficient to have captured the whole American army, and its defeat, therefore, was considered a real triumph. The loss of the Americans during the siege was about two hundred and sixty men killed and wounded. The loss of the enemy is unknown; but supposed to be as great. The excessive ardor of the troops, who made the sortie on the 5th, was the cause of their losing so many men; otherwise, the loss of the besieged would have been small.

The repulse of the allies did not deter them from making a second attempt on the fort. Early in July, the Indians appeared in the vicinity of the fort, and occasional skirmishes took place between them and parties of Americans. About the 20th of that month, a large force of British and Indians the latter mostly from the fierce Winnebago tribe appeared before the fort, and endeavored by stratagem to draw the garrison from their works; but without effect. A short time after, dissensions broke out among the allies, and they raised the siege.

Defense of Fort Stephenson

The brilliant defense of Fort Stephenson was one of the most celebrated actions of this war. The fort was situated on the river Sandusky, about twenty miles distant from Lake Erie. At the time of this attack and defense, it was little more than a picketing surrounded by a ditch six feet in depth, and nine in width and had been considered by General Harrison as so untenable, that he advised its commander to retire upon the approach of an enemy. The garrison consisted of but one hundred and sixty men, commanded by Major George Croghan. On the 29th of July, General Harrison received intelligence of the retreat of the enemy from Fort Meigs, and of the probability of an attack upon Fort Stephenson. He immediately sent an order to Major Croghan, to abandon and set fire to the fort. But this order did not reach Croghan until the place was surrounded by the Indians, and then he did not think it advisable to comply.

On the 1st of August, the enemy’s gun boat appeared in sight; and their troops were shortly afterwards landed, with a howitzer, about a mile below the fort. Previous to the commencement of the operations, an officer was dispatched by the British commander, to demand the surrender of the garrison, to which a determined refusal was immediately returned by Major Croghan. The force of the enemy was supposed to consist of about five hundred regulars, and eight hundred Indians, the whole commanded by General Proctor. The enemy now opened a fire from the six pounders in their gun boats, as well as from the howitzer, which was continued during the night, with very little injury to the fort. The only piece of artillery in this post was a six pounder, which was occasionally fired from different quarters, to impress the enemy with a belief that there were several. The fire of the assailants having been principally directed against the northwestern angle of the fort, with the intention, as it was supposed, of storming it from that quarter, the six pounder was placed in such a position as to enfilade that angle, and masked so as to be unperceived. The firing was continued during the next day, and until late in the evening, when the smoke and darkness favoring the attempt, the enemy advanced to the assault. Two feints were made in the direction of the southern angle; and at the same time, a column of about three hundred and fifty proceeded to the attack of that of the northwest. When they arrived within thirty paces of this point, they were discovered, and a heavy fire of musketry opened upon them. The column, however, led by Colonel Short, continued to advance, and leaped into the ditch; but, at this moment, the embrasure was opened, and so well directed and raking a fire was poured in upon them from the six pounder, that their commander and many of the men were instantly killed; and the remainder made a disorderly and hasty escape. A similar fate attended the other column, commanded by Colonel Warburton. They were received, on their approach, by so heavy a fire, that they broke and took refuge in an adjoining wood. This affair cost the enemy twenty-five privates killed, besides a lieutenant, and the leader of the column, Colonel Short. Twenty-six prisoners were taken, and the total loss, including the wounded, was supposed to be about one hundred and fifty. The scene which followed the attack reflected the greatest credit on the Americans. Numbers of the enemy’s wounded were left lying in the ditch, to whom water and other necessaries were conveyed by the garrison, during the night, at the risk of their safety. A communication was cut under the picketing, through which many were enabled to crawl into the fort, where surgical aid, and all that the most liberal generosity could dictate, was administered to them.

About three o’clock in the morning, after their repulse, the enemy commenced a precipitate retreat, leaving behind them many valuable military articles. The defense of Fort Stephenson, achieved as it was by youth scarcely arrived at manhood, against a foe distinguished for his skill and bravery, and that too, with so small means of defense at the time subsisting, was certainly one of the most brilliant achievements of the war. The news of the repulse of the enemy was received with great exultation throughout the Union. Major Croghan was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel; and, together with his brave companions, received the thanks of Congress.

Americans Attack the Town of Malden

The brave and patriotic people of Kentucky, at the call of their venerable Governor, Isaac Shelby, raised a body of three thousand five hundred men for the service, under General Harrison. This formidable force arrived at Upper Sandusky, on the 12th of September. Nothing, however, was attempted until Harrison received the news that Commodore Perry had met and conquered the British fleet on Lake Erie. Then the army was conducted into Canada, and on the 27th, the American standard was floating over the town of Malden, from which Proctor had made a hasty retreat. The whole force of the enemy, consisting of about two thousand, regulars, Indians and militia, retreated along the rivers Detroit and Thames. General Harrison, with three thousand five hundred men, mostly volunteers, pursued, and early on the 3d of October, arrived at the river Thames, where a party of the enemy were captured in the act of destroying a bridge over a creek in the vicinity. In the pursuit, some skirmishing took place between the advance guard and a party of Indians, in which the Americans were victors. On the morning of the 5th of October, Harrison received information that the enemy was lying at a short distance awaiting the attack. Colonel Johnson was then sent forward to reconnoiter, and the troops were prepared for action.

The allied army was drawn up across a narrow isthmus, covered with beech trees, and formed by the river Thames on the left, and a swamp running parallel to the river on the right. The regulars were posted with their left on the river, supported by the artillery; while the Indians, under Tecumseh, were placed in a dense wood, with their right on a morass. In the order in which the American army was originally formed, the regulars and volunteer infantry were drawn up in three lines, in front of the British force; while the mounted volunteers were posted opposite to the Indians, with directions to turn their right flank. It was soon perceived, however, that the nature of the ground on the enemy’s right would prevent this operation from being attempted with any prospect of success. General Harrison therefore determined to change his plan of attack. Finding that the enemy’s regulars were drawn up in open order, he conceived the bold idea of breaking their ranks, by a charge of part of the mounted infantry. They were accordingly formed in four columns of double files, with their right in a great measure out of the reach of the British artillery. In this order they advanced upon the enemy, receiving a fire from the British lines, from which their horses at first recoiled. Recovering themselves, however, the column continued to advance with such ardent impetuosity, that both the British lines were immediately broken. Wheeling then on the enemy’s rear, they poured a destructive fire into his ranks; and in a few minutes the whole British force, to the number of about eight hundred men, threw down their arms, and surrendered to the first battalion of the mounted regiment, the infantry not having arrived in time to share the honor. Their commander, General Proctor, however, escaped with a small party of dragoons.

In the meantime, a more obstinate and protracted conflict had been waged with the Indians on the left. The second battalion of the mounted volunteers, under the immediate command of Colonel Johnson, having advanced to the attack, was received with a very destructive fire; and the ground being unfavorable for the operations of horse, they were dismounted, and the line again formed on foot. A severe contest now ensued; but at length the militia, under Governor Shelby, advancing to the aid of Colonel Johnson’s battalion, the Indians broke, and fled in all directions, pursued by the mounted volunteers.

A complete and brilliant victory was thus obtained by the American army over an enemy, who, though somewhat inferior in numbers, possessed very decided advantages in the choice of his position, as well as the experience of his officers and men. The battle was, indeed, chiefly fought by the mounted volunteers, to whose unprecedented charge against a body of regular infantry) posted behind a thick wood, the fortune of the day was principally owing. This novel manoeuvre, at variance with the ordinary rules of military tactics, reflects the highest credit on the general who conceived, and the troops who executed it. The whole of the American force fully performed its duty, as far as it was engaged. The venerable governor of Kentucky was seen at the head of the militia of his state, exciting their valor and patriotism by the influence of his personal example, and adding to the laurels he had acquired thirty years before, in a contest with the same enemy.

The trophies acquired by this victory were of the most gratifying nature. Besides a great quantity of small arms and stores, six pieces of brass artillery were captured, three of which had been taken, during the revolution, at Saratoga and Yorktown; and were part of the fruits of General Hull’s surrender. The prisoners amounted to about six hundred, including twenty-five officers, and were chiefly of the forty-first regiment. Of the Americans, seven were killed and twenty-two wounded; and of the British troop, twelve were killed and twenty-two wounded.

The Indians, however, suffered far more severely. The loss of thirty of their number killed was trifling, in comparison with that sustained by the death of Tecumseh, their celebrated leader. His intelligence and bravery were no less conspicuous on this occasion than in the preceding part of the war. He was seen in the thickest press of the conflict, encouraging his brethren by his personal exertions; and, at the conclusion of the contest, his body was found on the spot where he had resisted the charge of the mounted regiment. His death inflicted a decisive stroke on the confederacy of the Indians, from which it never recovered, and deprived the British troops of a most active and efficient auxiliary.

The consequences of this victory upon the interests of the Indian tribes, were soon perceived. Being cut off from their communications with the British posts in Canada, many of them sent deputations to General Harrison, to sue for peace. Previous to the engagement on the Thames, an armistice had been concluded with the Ottawas and Chippewas, on condition of their raising the tomahawk against the British: and soon afterwards the Miamis and Potawatomi submitted on the same terms.

Citations:

- Ramsay[↩]