Nearly ten years of peace succeeded the treaty of Greenville, an interval which proved little less destructive to the tribes of the north-west than the desolation of their last calamitous war. The devastating influence of intemperance was never more fearfully felt than in the experience of these Indian nations at the period whose history we are now recording. General Harrison, then commissioner for Indian affairs, reported their condition in the following terms: “So destructive has been the progress of intemperance among them, that whole villages have been swept away. A miserable remnant is all that remains to mark the names and situation of many numerous and warlike tribes. In the energetic language of one of their orators, it is a dreadful conflagration, which spreads misery and desolation through their country, and threatens the annihilation of the whole race.”

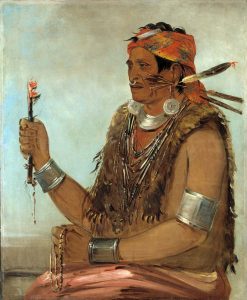

The Prophet Elskwatawa

While this deadly evil was constantly increasing, in the year 1804, a distinguished Indian orator began to excite a wide-spread discontent among the nations of the former north-western confederacy. This was the self-styled prophet, Elskwatawa, Olliwayshila, or Olliwachaca. About the year 1770, a woman of one of the southern tribes, domesticated with the Shawanees, according to report, became mother to three children at a single birth, who received the names of Tecumseh, Elskwatawa, and Kumshaka the last being unknown to fame. Their father, a Shawanee warrior, perished in the great battle at Point Pleasant. By the time that Tecumseh had attained the age of man hood, he had already become noted as a bold and sagacious warrior. For years before the overthrow of the Indian power by General Wayne, he had been foremost in the incursions which spread desolation throughout the western settlements; and when the peace, concluded at Greenville, deprived him of a field for warlike enterprise, he only retired to brood over new mischief, and, in conjunction with his brother, the Prophet, to excite a more extensive conspiracy than had ever before been perfected.

With consummate art, Elskwatawa exposed the evils attendant on the white man s encroachments, exhorting to sobriety and a universal union for resistance. He pro claimed himself especially commissioned by the Great Spirit to foretell, and to hasten, by his own efforts, the destruction of the intruders, and by various, appeals to the vanity, the superstition, and the spirit of revenge, of his auditors, he acquired a strong and enduring influence. The chiefs who opposed or ridiculed his pretensions were denounced as wizards or sorcerers, and proofs, satisfactory to the minds of the Indians, being adduced in support of the accusation, numbers perished at the stake, leaving a clear field for the operations of the impostor.

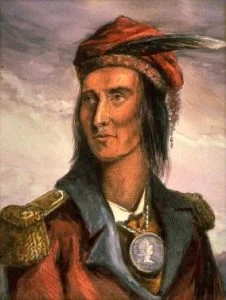

Tecumseh: His Plans And Intrigues

Tecumseh, meanwhile, was not idle. It is said that the noted Seneca chief, Red-Jacket, first counseled him to set about the work to which he devoted his life, holding out to him the tempting prospect of a recovery of the rich and extensive valley of the Mississippi from the possession of the whites. Whatever originated the idea in his mind, he lent all the powerful energy of his character to its accomplishment. The tribes concerned in the proposed outbreak were mostly the same that had in earlier times been aroused by Pontiac, and had again united, under Michikinaqua, as we have seen in the preceding chapter. The undertaking of Tecumseh and his brother was not of easy or speedy accomplishment, but their unwearied efforts and high natural endowments gradually gave them both an unprecedented ascendancy over the minds of the Indians. In 1807, the new movement among the Western Indians called for attention on the part of the United States, and General, then Governor, Harrison dispatched a message of warning and reproach to the leading men of the Shawanee tribe. The Prophet dictated, in reply, a letter, in which he denied the charges circulated against him, and strenuously asserted that nothing was farther from his thoughts than any design of creating a disturbance. In the summer of the following year this subtle intriguer established himself on the Tippecanoe River, a tributary of the Wabash, in the northern part of the state of Indiana.

From this place, where he lived surrounded by a crowd of admiring followers, the Prophet proceeded shortly after to Vincennes, and spent some time in communication with Governor Harrison, for the purpose of disarming suspicion. He continually insisted that the whole object of his preaching to the Indians was to persuade them to relinquish their vices, and lead sober and peaceable lives; and to this effect he often exhorted his people in the presence of the United States government officials.

In September, of 1809, while Tecumseh was pushing his intrigues among various distant tribes, Governor Harrison obtained a cession, for certain stipulated annuities, of a large tract of land on the lower portion of the Wabash, from the tribes of the Miami, Delawares, Pottawatomie, and Kickapoo. On Tecumseh’s return in the following year, he, with his brother, made vehement remonstrances against this proceeding, and a somewhat stormy interview took place between the great chief and Governor Harrison, each party being attended by a powerful armed force. Upon this occasion, Tecumseh first openly avowed his design of forming an universal coalition of the Indian nations, by which the progress of the whites westward should be arrested, but he still insisted that it was not his intention to make war. One great principle which he endeavored to enforce was that no Indian lands should be sold, except by consent of all the con federate tribes. Two days after this conference he started for the south, with a few attendant warriors, to spread disaffection among the Creeks, Cherokees, and other tribes of the southern states.

In the following year, (1811,) during the prolonged absence of Tecumseh, and contrary, as is supposed, to his express instructions, bold and audacious depredations and murders were committed by the horde of savages gathered at the Prophet s town. Representations were forwarded to Washington of the necessity for active measures in restraint of these outrages, and a regiment, under Colonel Boyd, was promptly marched from Pittsburg to Vincennes, and placed under the command of Harrison. With this force, and a body of militia and volunteers, the whole amounting to about nine hundred men, the governor marched from Fort Harrison, on the Wabash, for the Prophet’s town, on the 8th of October. He had previously made various attempts, through the intervention of some friendly Delaware and Miami chiefs, to bring about a negotiation, a restoration of the stolen property, and a delivery up of the murderers; but his emissaries were treated with contempt, and his proposals spurned.

The march was conducted with the greatest military skill. A feint was made of taking up the line of march on the south bank of the river; after which, the whole army crossed the stream, and hastened towards the hostile settlement through the extensive prairies, stretching farther than the eye could reach towards the west. On the 5th of November, having met with no opposition on the route, Harrison encamped within nine miles of the Prophet s town. Approaching the town on the ensuing day, various futile attempts were made to open a conference. Menaces and insults were the only reply to these overtures. Before the troops reached the town, however, messengers from Elskwatawa came forward, proposing a truce, and the arrangement for a conference upon the following day. The chief averred that he had sent a pacific embassy to the governor, but that those charged with the mission had gone down the river on the opposite bank, and thus missed him. Harrison assented to a cessation of hostilities until the next day, but took wise precautions for security against a treacherous night attack.

The suspicions of the prudent general proved to be well founded. The darkness of the night favored the designs of the Indians, and, before daybreak, about four o clock, the alarm of an attack was given. In the words of one of Harrison s biographers: ” The treacherous Indians had stealthily crept up near our sentries, with the intention of rushing upon them and killing them before they could give the alarm. But fortunately one of the sentries discovered an Indian creeping towards him through the grass, and fired at him. This was immediately followed by the Indian yell, and a furious charge upon the left flank.”

The onset of the Indians, stimulated as they were by the assurances of their prophet, that certain success awaited them, was unprecedented for fury and determination. They numbered from five hundred to a thousand, and were led by White Loon, Stone-Eater, and a treacherous Pottawatomie chief named Winnemac. The Prophet took, personally, no share in the engagement. The struggle continued until daylight, when the assailants were driven off and dispersed. Great praise has been deservedly awarded to the commanding officer of the whites for his steady courage and generalship during the trying scenes of this night s encounter. The troops, although no small number of them were now, for the first time, in active service, displayed great firmness and bravery. The Indians immediately abandoned their town, which the army proceeded to destroy, tearing down the fortifications and burning the buildings. The object of the expedition being thus fully accomplished, the troops were marched back to Vincennes.

Defeat Of The Indians At Tippecanoe

In the battle at Tippecanoe, the loss of the victors was probably greater than that of the savages. Thirty-eight of the latter were left dead upon the field: of the whites, fifty were killed, and nearly one hundred wounded. It is not to be supposed that the Prophet’s influence maintained its former hold upon his followers after this defeat. He takes, indeed, from this time forward, a place in history entirely subordinate to his warlike and powerful brother.

An interval of comparative quiet succeeded this over throw of the Prophet s concentrated forces, a quiet destined to be broken by a far more extensive and disastrous war. When open hostilities commenced between England and the United States, in 1812, it was at once evident that the former country had pursued her old policy of rousing up the savages to ravage our defenseless frontier, with unprecedented success. Tecumseh proved a more valuable coadjutor, if possible, than Brant had been during the Revolution, in uniting the different nations against the American interests.

To particularize the part taken by this great warrior and statesman in the war, would involve too prolonged a description of the various incidents of the western campaigns. By counsel and persuasion; by courage in battle; and by the energy of a powerful mind devoted to the cause he had espoused, he continued until his death to aid his English allies. A strong British fortress at Maiden, on the eastern or Canada shore of Detroit River, proved a rendezvous for the hostile Indians, of the utmost danger to the inhabitants of the north-western frontier. The place was under the command of the British General Proctor; the officer whose infamous neglect or countenance led to the massacre of a body of wounded prisoners at French-town, on the river Raisin, in January 1813. This post was abandoned by the British and Indians, about the time of the invasion of Canada, in September, of the above year, by the American troops under Harrison. The invading army encamped at the deserted and dismantled fortress, “from which had issued, for years past, those ruthless bands of savages, which had swept so fiercely over our extended frontier, leaving death and destruction only in their path.”

Harrison’s Invasion Of Canada

General Harrison hastened in pursuit of the enemy up the Thames River, and, on the 4th of October, encamped a few miles above the forks of the river, and erected a slight fortification. On the 5th, the memorable battle of the Thames was fought. General Proctor awaited the approach of the American forces at a place chosen by him self, near Moravian town, as presenting a favorable position for a stand. His forces, in regulars and Indians, rather outnumbered those of his opponents, being set down at two thousand eight hundred; the Americans numbered twenty-five hundred, mostly militia and volunteers. The British army “was flanked, on the left, by the river Thames, and supported by artillery, and on the right by two extensive swamps, running nearly parallel to the river, and occupied by a strong body of Indians. The Indians were commanded by Tecumseh in person.”

The British line was broken by the first charge of Colonel Johnson s mounted regiment, and being thrown into irretrievable disorder, the troops were unable to rally, or op pose any further effective resistance. Nearly the whole army surrendered at discretion. Proctor, with a few companions, effected his escape. The Indians, protected by the covert where they were posted, were not so easily dislodged. They maintained their position until after the defeat of their English associates and the death of their brave leader. By whose hand Tecumseh fell, does not appear to be decisively settled; but, according to the ordinarily received account, he was rushing upon Colonel Johnson with his tomahawk, when the latter “shot him dead with a pistol.

Battle Of The Thames, And Death Of Tecumseh

This battle was, in effect, the conclusion of the northwestern Indian war. Deputations from various tribes appeared suing for peace; and during this and the ensuing year, when Generals Harrison and Cass, with Governor Shelby, were appointed commissioners to treat with the Northwestern tribes, important treaties were affected.

Tecumseh was buried near the field of battle, and a mound still marks his grave. The British government, not unmindful of his services, granted a pension to his widow and family, as well as to the Prophet Elskwatawa.