When Governor Stevens returned to his capital from the Blackfoot Country, he was to some extent deceived as to the perils which threatened the Puget Sound region. He approved of the energetic course of Mason, and advocated the vigorous prosecution of the war. But from what he had seen east of the Cascades, and from what he knew of the indolent habits of the tribes on the Sound, he was disposed to think the war was to be carried on in the Yakima and Walla Walla valleys rather than at home.

In a special message delivered extemporaneously to the legislative assembly, January 21, 1856, three days after arriving in Olympia, he recited the history of the war as he understood it. The people of the territory, he said, had urged upon congress the importance to them of extinguishing the Indian title to the country. To this the Indians consented with apparent willingness. Being appointed a commissioner to treat with them, he had applied himself to the duty, and successfully treated with the different tribes, explaining to them with the most minute care the terms to which they had agreed. But the Indians had acted treacherously, inasmuch as it was now well known that they had long been plotting against the white race, to destroy it. This being true, and they having entered upon a war without cause, however he might sympathize with the restlessness of an inferior race who perceived that destiny was against them, he nevertheless had high duties to perform toward his own, and the Indians must be met and resisted by arms, and that without delay, for seed-time was coming, when the farmers must be at the plough. The work remaining to be done, he thought, was comparatively small. Three hundred men from the Sound to push into the Indian country, build a depot, and operate vigorously in that quarter, with an equal force from the Columbia to prosecute the war east of the Cascades, in his opinion should be immediately raised. The force east of the mountains would prevent reinforcements from joining those on the west, and vice versa, while their presence in the country would prevent the restless but still faltering tribes farther north from breaking out into open hostilities. There should be no more treaties; extermination should be the reward of their perfidy.

On the 1st of February, in order to facilitate the organization of the new regiment, Stevens issued an order disbanding the existing organization, and revoking the orders raised for the defense of particular localities. The plan of block-houses was urged for the defense of settlements even of four or five families, 1 the number at first erected being doubled in order that the farmers might cultivate their land; and in addition to the other companies organized was one of pioneers, whose duty it was to open roads and build block-houses.

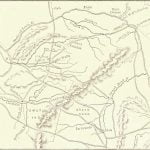

The first regiment being disbanded, the reorganization progressed rapidly, and on the 25th the second regiment was organized into three battalions, designated as the northern, central, and southern; the northern battalion to rendezvous at the falls of the Snoqualimich and elect a major, the choice falling upon Captain J. J. H. Van Bokelin. 2 It numbered about ninety men, supported by Patkanim and his company of Indian allies, and built forts Tilton and Alden below and above the falls. 3 The central battalion was commanded by Major Gilmore Hays, and had its headquarters on Connell’s prairie, White River, 4 communicating with the rear by a ferry and block-house on the Puyallup, and block-houses at Montgomery’s, and on Ye1m prairie, besides one at the crossing of White River, communicating with the regular forces at Muckleshoot prairie and Porter’s prairie, farther up the valley.

The southern battalion, organized by Lieutenant- colonel B. F. Shaw, was raised upon the Columbia River, and partly of Oregon material, 5 obtained by advertising for volunteers in the Oregon newspapers. Other companies were accepted from time to time as the exigencies of the service required, until there were twenty-one in the field, the whole aggregating less than a thousand men. The regiment was assigned to duty, and furnished with supplies with military skill by the commander-in-chief, whose staff-officers, wisely chosen, 6 kept the machinery of war in motion, the detention of which so often paralyzed the arms of Governor Curry’s volunteers. Between Curry and Stevens there was perfect harmony, the latter often being assisted by the governor of Oregon in the purchase of supplies, a service which was always gratefully acknowledged.

The plan of the campaign as announced by Stevens was to guard the line of the Snohomish and Snoqualimich pass by the northern battalion, to drive the enemy into the Yakima country with the central battalion by the Nachess pass, and to operate east of the Cascade Range with the southern battalion. On the occasion of the governor’s reconnaissance of the Sound, which took place in January, the Snoqualimich chief Patkanim tendered his services as an ally, and upon consultation with Agent Simmons was accepted. He at once took the field with fifty-five well- armed warriors, accompanied by Simmons, L. M. Collins, and T. H. Fuller. On the 8th of February they reached Wappato prairie, five miles below the falls of the Snoqualimich, and learning that there was an encampment of the hostile Indians at the falls, Patkanim prepared to attack them, which he did, capturing the whole party. An investigation showed them to be Snoqualimichs, with the exception of three Klikitat emissaries engaged in an endeavor to enlist them on the side of the hostile combination. Patkanim, however, now that he had entered upon duty as an ally of the white people, carried his prisoners to camp at Wappato prairie and tried them each and every one, the trial resulting in the discharge of the Snoqualimichs, and one of the Klikitats, whose evidence convicted the other two and caused them to be hanged. Their heads were then cut off and sent to Olympia, where a price was to be paid.

From the Klikitat who was allowed to live it was ascertained that there were four different camps of the enemy on the east side of White River, at no great distance apart, above the point where the military road crossed it, and that Leschi was at one of them, while the crossing of the river was guarded above and below. This information was immediately sent to Olympia.

Patkanim at once proceeded to White River to attack Leschi, whom it was much desired by the government to arrest. But when he arrived there he found that wily chief alert and on his guard. Being strongly posted in the fork of a small tributary of White River, a sharp engagement followed, resulting in considerable loss. Of the number killed by Patkanim, all but two were on the farther side of the stream, and he was able to obtain but two heads, which were also forwarded to Olympia.. He returned after this battle to Holme Harbor, Whidbey Island, to prepare for further operations, it now being considered that he had fully committed himself to the cause of the white people. He remained faithful, and was of some further assistance, but objected to be commanded by white officers, preferring his own mode of fighting.

About the 13th of February Captain Maloney left Fort Steilaeoom with Lieutenants Davis and Fleming and 125 men, for the Puyallup, where he constructed a ferry and block-house, after which he moved on to White River, Colonel Casey, who had arrived on the steamship Republic in command of two companies of the regular 9th infantry, following a few days later with about an equal number of men.

On the 22d Captain Ford of the volunteers left Steilacoom for White River with his company of Chehalis scouts, in advance of Hays’ company, and White’s pioneers, who followed after, establishing depots at Yelm prairie and Montgomery’s, and moving on to the Puyallup, where they built a blockhouse and ferry, after which, on the 29th, they proceeded to the Muckleshoot prairie, Henness following in a few days with his company, a junction being formed with Casey’s and Maloney’s commands at that place, Governor Stevens himself taking the field on the 24th, when the volunteers moved to the Puyallup.

Up to this date the war had been confined to the country north of Steilacoom, although a wide-spread alarm prevailed throughout the whole country. But the watchful savages were quick to perceive that by the assemblage of the regular and volunteer forces in the White River country they had left their rear comparatively unguarded, and on the 24th attacked and killed, near Steilacoom, William Northcraft, in the service of the territory as a teamster, driving off his oxen and the stock of almost every settler in the vicinity. On the 2d of March they waylaid William White, a substantial farmer living near Nathan Eaton’s place, which was subsequently fortified, killing him and shooting at his family, who were saved by the running-away of the horses attached to a wagon in which all were returning from church. A family was also attacked while at work in a field, and some wounds received. These outrages were perpetrated by a band of forty savages under the leadership of chiefs Stahi and Quiemuth, who had flanked the troops in small detachments, and while Casey’s attention was diverted by the voluntary surrender of fifty of their people, most of whom were women and children, whom it was not convenient to support while at war, but which were taken in charge by the Indian department. This new phase of affairs caused the governor’s return to Olympia, whence he ordered a part of the southern battalion to the Sound. On the 4th of March, a detachment of regulars under Lieutenant Kautz, opening a road from the Puyallup to Muckleshoot prairie, when at no great distance from White River, discovered Indians and attacked them, Kautz sheltering his men behind piles of driftwood until Keyes reinforced him, when the battle was carried across the river and to the Muckleshoot prairie, where a charge being made, the Indians scattered. There were over a hundred regulars in the engagement, one of whom was killed and nine wounded, including Lieutenant Kautz. The loss of the Indians was unknown.

In the interim the volunteers of the central battalion had reached Connell’s prairie, where an encampment was formed. On the morning of the 8th Major Hays ordered Captain White’s company of pioneers, fifty strong, to the crossing of White River, to erect a block-house and construct a ferry, supported only by Captain Swindal with a guard of ten men. They had not proceeded more than a mile and a half from camp before the advance under Lieutenant Hicks was attacked by 150 warriors, who made a furious assault just as the detachment entered the woods that covered the river-bottoms, and were descending a hill. Almost simultaneously the main company received a heavy fire, and finding the odds against him, ‘White dispatched a messenger to camp, when he was reinforced by Henness with twenty men, and soon after by Martin with fifteen. The battle continuing, and the Indians making a flank movement which could be seen from camp, Van Ogle was dispatched with fifteen men to check it. So rapid were their maneuvers that it required another detachment of twelve men under Rabbeson to arrest them.

The Indians had a great advantage in position, and after two hours of firing, a charge was ordered to be made by a portion of the volunteers, while White’s company and Henness’ detachment held their positions. The charge was successful, driving one body of the Indians through a deep marsh, or stream, in their flight, and enabling Swindal to take a position in the rear of the main body on a high ridge. It being too dangerous to charge them from their front, where White and Henness were stationed, they being well fortified behind fallen timber on the crest of a hill, Rabbeson and Swindal were ordered to execute a flank movement, and attack the enemy in the rear. A charge being made simultaneously in front and rear, the Indians were completely routed, with a loss of between twenty-five and thirty killed and many wounded. The loss of the volunteers was four wounded.

This battle greatly encouraged the territorial troops. The Indians were in force, outnumbering them two to one; they had chosen their position, and made the attack, and were defeated with every circumstance in their favor. 7

This affair was the most decisive of the spring campaign of 1856 on the Sound. After it the Indians did not attempt to make a stand, but fought in small parties at unexpected times and in unexpected places. It would indeed have been difficult for them to have fought a general engagement, so closely were they pursued, and so thickly was the whole country on the east side dotted over with block-houses and camps. The blockhouse at the crossing of White River was completed, the Indians wounding one of the construction party by firing from a high bluff on the opposite bank. A station was made at Connell’s prairie, called Fort Hays, by the volunteers, and another, called Fort Slaughter, on the Muckleshoot prairie, by the regulars. A blockhouse was established at Lone Tree point, three miles from the Dwamish, where Riley’s company was stationed to guard the trail to Seattle. Later Lieutenant-colonel Lander with company A erected a blockhouse on the Dwamish, fifteen miles from Seattle. Captain Maloney erected one on Porter’s prairie, and Captain Dent another at the mouth of Cedar River. The northern battalion, after completing their works on the Snoqualimich and leaving garrisons, marched across the country to join the central battalion by order of the commander-in-chief; and Colonel Shaw of the southern battalion added his force to the others about the last of the month.

At this juncture Governor Stevens proclaimed martial law; his forces were readjusted, and a desultory warfare kept up throughout the entire region. On John Day River, where the enemy had congregated in numbers, Major Layton of the Oregon volunteers captured thirty-four warriors in June, and in July there was some fighting, but nothing, decisive. Colonel Shaw also did some fighting in the Grand Rond country, but there, as elsewhere, the Indians kept the army on the move without definite results.

In these white raids many Indian horses were taken, and all government supplies stopped. Obviously no more effective method of subduing the Indians could be adopted than to unhorse them and take away their supplies. The march of the several detachments of regulars and volunteers through the Indian country forced the neutral and needy Indians to accept the overtures of the United States government through the Indian and military departments, and they now surrendered to the agents and army officers, to the number of 923, comprising the Wasco, Tyghe, Des Chutes, and a portion of the John Day tribes, all of whom were partially subsisted by the government. About 400 of the Yakimas and Klikitats who surrendered to Colonel Wright during the summer were also assisted by the government agents.

Soon after a battle on the Grand Rend, Major Layton mustered out his battalion, the time of the Oregon troops having expired, leaving only Shaw’s battalion in the Walla Walla Valley, to hold it until Colonel Wright should be prepared to occupy it with the regular troops, who had not fought nor attempted to fight an engagement during the summer. A scouting party of Jordan’s Indian allies, in recovering 200 captured horses, killed two hostile Indians, the sole achievement of a regiment of troops in the field for four months. About the 1st of August Wright returned to Vancouver, leaving Major Garnett in command of Fort Simcoe, and the Indians at liberty to give the volunteers employment, which they were ready enough to do. 8

Governor Stevens was unable to push forward any troops east of the Cascade Range for two months after the Oregon troops were withdrawn upon the understanding that Colonel Wright was to occupy the Walla Walla Valley. In the mean time the hostile tribes enjoyed the fullest liberty up to the appearing of the southern battalion, and those previously friendly, being in ignorance of the intention of the authorities toward them, made this an excuse for withdrawing their allegiance.

Lieutenant-colonel Craig, who with his auxiliaries had been using his best endeavors to hold the Nez Percé and Spokanes constant to their professions, met the volunteers in the Walla Walla Valley, and escorted Captain Robie with the supply train under his charge to the Nez Percé country. On the 24th of July Robie returned and communicated to Colonel Shaw, just in from the Grand Rond expedition, the disagreeable intelligence that the Nez Percé had shown a hostile disposition, declaring the treaty broken, and refusing to receive the goods sent thein 9 This would have been unwelcome news at any time, but was most trying at this juncture, when half the force in field was quitting it to be mustered out of service. This exigency occasioned the call for two more companies of volunteers. Subsequent to making the call, Stevens decided to go in person to Walla Walla, and if possible to hold a council. A messenger was at once dispatched to Shaw, with instructions to send runners to the different tribes, friendly and hostile, inviting them to meet him on the 25th; but accompanying the invitation was the notice that he required the unconditional surrender of the warring bands.

Stevens urged Colonel Wright to be present at the council, and to send three companies of regulars, including all his mounted men, to the Walla Walla Valley for that occasion. Wright declined the invitation to participate in the council, but signified his intention of sending Steptoe to Walla Walla to establish a post in that country.

On the 19th of August, Stevens set out from The Dalles with a train of 30 wagons, 80 oxen, and 200 loose animals, attended only by his messenger, Pearson, and the employees of the expedition. A day or two behind him followed the baggage and supply train of Steptoe’s command. He arrived without accident at Camp Mason on the 23d, sending word in all directions to inform the Indians of his wish to meet them for a final adjustment of their difficulties at the council ground five miles from Waiilatpu. At the end of a week a deputation of the lower Nez Percé had come in with their agent, Craig. At the end of another week all this tribe were in, but on the same day Father Ravelli, from the Coeur d’Alene Mission, arrived alone, with the information that he had seen and conversed with Kamiakin, Owhi, and Qualchin, who refused to attend the council, and also that the Spokanes and other tribes declined to meet the superintendent, having been instigated to this course by Kamiakin, who had made his headquarters on the border of their country all summer, exercising a strong influence by the tales he circulated of the wrong-doing of the white people, and especially of Governor Stevens, and enmity among the northern tribes.

On the 10th the hostile Cayuses, Des Chutes, and Tyghes arrived and encamped in the neighborhood of the Nez Percé, but without paying the customary visit to Governor Stevens, and exhibiting their hostility by firing the grass of the country they traveled over. They had recently captured a pack train of forty-one horses and thirty packs of provisions from The Dalles for Shaw’s command, and were in an elated mood over their achievement.

The council opened on the 11th of September, and closed on the 17th, Stevens moving his position in the mean time to Steptoe’s camp for fear of an outbreak. Nothing was accomplished. The only terms to which the war chiefs would assent were to be left in possession of their respective domains. On his way back to The Dalles with his train of Indian goods, escorted by Shaw’s command under Goff, on the 19th and 20th several attacks were made and two soldiers killed. Assisted by Steptoe, Stevens finally reached his destination in safety. After this mortifying repulse Governor Stevens returned to the Sound. Wright repaired to Walla Walla with an additional company of troops, and sent word to all the chiefs to bring them together for a council. Few came, the Nez Percé being represented by Red Wolf and Eagle-from-the light, the Cayuses by Howlish Wampo, Tintinmetse, and Stickas, with some other sub-chiefs of both nations. None of the Yakimas, Des Chutes, Walla Wallas, or Spokanes were present; and all that could be elicited from those who attended the council was that they desired peace, and did not wish the treaty of Walla Walla confirmed.

Wright remained at Walla Walla until November, the post of Fort Walla Walla 10 being established on Mill Creek, six miles from its junction with the Walla Walla River, where the necessary buildings were completed before the 20th. In November Fort Dalles was garrisoned by an additional company under brevet Major Wise. The Cascade settlement was protected by a company of the 4th infantry under Captain Wallen, who relieved Captain Winder of the 9th infantry. The frontier being thus secured against invasion, the winter passed without many warlike demonstrations.

About the 20th of July the volunteer companies left on the Sound when Shaw’s battalion departed for Walla Walla were disbanded, the hostile Indians being driven east of the mountains, and the country being in a good state of defense. On the 4th of August Governor Stevens called a council of Indians at Fox Island, to inquire into the causes of discontent, and finding that the Nisquallies and Puyallups were dissatisfied with the extent of their reservation, not without a show of reason, he agreed to recommend an enlargement, and a resurvey was ordered on the 28th, which took in thirteen donation claims, for which congress appropriated nearly $5,000 to pay for improvements.

Having satisfied the Indians of his disposition to deal justly with them, he next made a requisition upon Colonel Wright for the delivery to him of Leschi, Quiemuth, Nelson, Stahi, and the younger Kitsap, to be tried for murder, these Indians being among those who had held a council with Wright in the Yakima country, and been permitted to go at large on their parole and obligation to keep the peace. But ‘Wright was reluctant to give up the Indians required, saying that although he had made no promises not to hold them accountable for their former acts, he should consider it unwise to seize them for trial, as it would have a disturbing effect upon the Indians whom he was endeavoring to quiet. Stevens argued that peace on milder terms would be a criminal abandonment of duty, and would depreciate the standing of the authorities with the Indians, especially as he had frequently assured them that the guilty should be punished; he repeated his requisition; whereupon, toward the last of the month, Major Garnett was ordered to turn over to the governor for trial the Indians named. The army officers were not in sympathy with what they deemed the arbitrary course of the governor, and Garnett found it easy to evade the performance of so uncongenial a duty, the Indians being scattered, and many of them having returned to the Sound, where they gave themselves up to the military authorities at Fort Steilacoom.

A reward, however, was offered for the seizure and delivery of Leschi, which finally led to his arrest about the middle of November. It was accomplished by the treachery of two of his own people, Sluggia and Elikukah. They went to the place where Leschi was in hiding, poor and outlawed, having been driven away by the Yakimas who had submitted to Wright, who would allow him to remain in their country only on condition that he became their slave; and having decoyed him to a spot where their horses were concealed, suddenly seized and bound him, to be delivered up to Sydney S. Ford, who surrendered him to Stevens at Olympia.

The particular crime with which Leschi was charged was the killing of A. B. Moses, the place being in Pierce County. Court had just adjourned when he was brought in, but as Judge Chenoweth, who resided on Whidbey Island, had not yet left Steilacoom, he was requested by the governor to hold a special term for the trial of Leschi, and the trial came off on the o 17th of November, the jury failing to agree. A second trial, begun on the 18th of March 1857, resulted in conviction, and the savage was sentenced to be hanged on the 10th of June. This action of the Governor was condemned by the regular army officers, there being in this case the same opposition of sentiment between the civil and military authorities which had existed in all the Indian wars in Oregon and Washington-the army versus the people.

Proceedings were instituted to carry the case up to the Supreme Court in December, which postponed the execution of the sentence. The opinion of McFadden, acting chief justice, sustained the previous action of the district court and the verdict of the jury. Leschi’s sentence was again pronounced, the day of his execution being fixed upon the 22d of January 1858. In the mean time Stevens had resigned, and a new governor, McMullin, had arrived, to whom a strong appeal was made by the counsel and friends of Leschi, but to no effect, 700 settlers protesting against pardon. When the day of execution arrived, a large concourse of people assembled at Steilacoom to witness the death of so celebrated a savage. But the friends of the doomed man had prepared a surprise for them. The sheriff of Pierce county and his deputy were arrested, between the hours of ten and twelve o’clock, by Lieutenant McKibben of Fort Steilacoom, appointed United States marshal for the purpose, and Frederick Kautz, upon a warrant issued by J. M. Baclielder, United States commissioner and sutler at that post, upon a charge of selling liquor to the Indians. An attempt was made by Secretary Mason to obtain the death-warrant in possession of the sheriff, which attempt was frustrated until after the hour fixed for the execution had passed, during which time the sheriff remained in custody with no attempt to procure his freedom.

So evident a plot, executed entirely between the prisoner’s counsel and the military authorities at Fort Steilacoom, aroused the liveliest indignation on the part of the majority of the people. A public meeting was held at Steilacoom, and also one at Olympia, on the evening of the 22d, at which all the persons in any way concerned in the frustration of the sentence of the courts were condemned, and the legislature requested to take cognizance of it. This the legislature did, by passing an act on the following day requiring the judges of the supreme court to hold a special session on or before the 1st of February at the seat of government, repealing all laws in conflict with this act, and also passing another act allowing the judges, Chenoweth and McFadden, Lander being absent from the territory, one hundred dollars each for their expenses in holding an extra session of the supreme court, by which the case was remanded to the court of the 2d judicial district, whither it came on a writ of error, and an order issued for a special session of the district court, before which, Chenoweth presiding, Leschi was again brought, when his counsel entered a demurrer to its jurisdiction, which was overruled, and Leschi was for the third time sentenced to be hanged; and on the 19th of February the unhappy savage, ill and emaciated from long confinement, and weary of a life which for nearly three years had been one of strife and misery, was strangled according, to law.

There is another case on the record according the temper of the time. Shortly after Leschi’s betrayal and arrest, Quiemuth, who had been in hiding, presented himself to George Brail on Yelm prairie, with the request that he should accompany him to Olympia, and give him up to Governor Stevens to be tried. Brad did as requested, three or four others accompanying him. Arriving at Olympia at half-past two in the morning, they aroused the governor, who, placing them all in his office, furnished fire and refreshments, locked the front door, and proceeded to make arrangements for conveying the party to Steilacoom before daylight.

Although caution was used, the fact of Quiemuth’s presence in the town became known, and several persons quietly gained access to the governor’s office through a back door, among whom was James Bunton, a son-in-law of James McAllister, who was killed while conversing with some of Leschi’s people. The guard saw no suspicious movement, when suddenly a shot was fired, there was a quick arousal of all in the room, and Quiemuth with others sprang to the door, where he was met by the assassin and mortally stabbed. So dimly lighted was the room, and so unexpected and sudden was the deed, that the perpetrator was not recognized, although there was a warrant issued a few hours later for Bunton, who, on examination, was discharged for want of evidence. 11

Few of the Indian leaders in the war on the Sound survived it. Several were hanged at Fort Steilacoom; three were assassinated by white men out of revenge; Kitsap was killed in June 1857, on the Muckleshoot prairie, by one of his own people, and in December following Sluggia, who betrayed Leschi, was killed by Leschi’s friends. 12 Nelson and Stahi alone survived when Leschi died. His death may be said to have been the closing act of the war on Puget Sound; but it was not until the ratification of the Walla Walla treaties in 1859 that the people returned to their farms in the Puyallup and upper White River valleys. 13 So antagonistic was the feeling against Stevens conduct of the war at the federal capital, that it was many years before the war debt was allowed.

The labors of the commission appointed to examine claims occupied almost a year, to pay for which congress appropriated twelve thousand dollars. The total amount of war expenses for Oregon and Washington aggregated nearly six millions of dollars! 14 When the papers were all filed they made an enormous mass of half a cord in bulk, which Smith took to Washington in 1857. 15 The secretary of war, in his report, pronounced the findings equitable, recommending that provision should be made for the payment of the full amount. 16

The number of white persons known to have been killed by Indians 17 in Oregon previous to the establishment of the latter on reservations, including the few fairly killed in battle, so far as I have been able to gather from reliable authorities, was nearly 700, besides about 140 wounded who recovered, and without counting those killed and wounded in Washington. 18

Two events of no small significance occurred in the spring of 1857, the union of the two Indian superintendencies of Washington under one superintendent, J. W. Nesmith of Oregon, and the recall of General Wool from the command of the department of the Pacific. The first was in consequence of the heavy expenditures in both superintendencies, and the second was in response to the petition of the legislature of Oregon at the session of 1856-7. The successor of Wool was Newman S. Clarke, who paid a visit to the Columbia River district in June. 19

Nesmith did not relieve Stevens of his duties as superintendent of Washington until the 2d of June, 20 soon after which General Clarke paid a visit to the Columbia River district to look into the condition of this portion of his department.

Nesmith recommended to the commissioner at Washington City that the treaties of 1855 be ratified, as the best means of bringing about a settlement of the existing difficulties, and for these reasons: that the land laws permitted the occupation of the lands of Oregon and Washington, regardless of the rights of the Indians, making the intercourse laws a nullity, and rendering it impossible to prevent collisions between them and the settlers. Friendly relations could not be cultivated while their title to the soil was recognized by the government, which at the same time failed to purchase it, but gave white people a right to settle in the country.

About the middle of April 1858 Colonel Steptoe notified General Clarke that an expedition to the north seemed advisable, if not absolutely necessary, as a petition had been received from forty persons living at Colville for troops to be sent to that place, the Indians in the vicinity being hostile. Two white men en route for Colville mines had been killed by the Palouses, who had also made a foray into the Walla Walla country and driven off the cattle belonging to the army. On the 6th of May Steptoe left Walla Walla with 130 dragoons, proceeding toward the Nez Percé country in a leisurely manner. At Snake River he was ferried across by Timothy, who also accompanied him as guide. At the Alpowah he found thirty or forty of the Palouses, who were said to have killed the two travelers, who fled on his approach. On the 16th he received information that the Spokanes were preparing to fight him, but not believing the report, pursued his march northward 21 until he found himself surrounded by a force of about 600 Indians in their war-paint-Palouses, Spokanes, Coeur d’Alenes, and a few Nez Percé. They had posted themselves near a ravine through which the road passed, and where the troops could be assailed on three sides. The command was halted and a parley held with the Spokanes, in which they announced their intention of fighting, saying that they had heard the troops had come to make war on them, but they would not be permitted to cross the Spokane River.

Informing his officers that they should be compelled to fight, Steptoe turned aside to avoid the dangerous pass of the ravine, and coming in about a mile to a small lake, encamped there, but without daring to dismount, the Indians having accompanied them all the way at a distance of not more than a hundred yards, using the most insulting words and gestures. No shots were fired, either by the troops or Indians, Steptoe being resolved that the Spokanes should fire the first gun; and indeed, the dragoons had only their small arms, and were not prepared for fighting Indians. 22

Toward night a number of chiefs rode up to the camp to inquire the occasion of the troops coming into the Spokane country, and why they had cannon with them. Steptoe replied that he was on his way to Colville to learn the causes of the troubles between the miners and Indians in that region. This the Indians professed to him to accept as the true reason, though they asserted to Father Joset that they did not believe it, because the colonel had not taken the direct road to Colville. 23 But had come out of his way to pass through their country-a fact of which Steptoe was himself unconscious, having trusted to Timothy to lead him to Colville. But though the chiefs professed to be satisfied, they refused to furnish canoes to ferry over the troops, and maintained an unyielding opposition to their advance into the Spokane country. Finding that he should have to contend against great odds, without being prepared, Steptoe determined upon retreating, and early on the morning of the 17th began his return to the Palouse.

In the mean time the Coeur d’Alenes, who were gathering roots in a Camas prairie a few miles distant, had been informed of the position of affairs, and were urged to join the Spokanes, who could not consent to let the troops escape out of their hands so easily. As they were about marching, Steptoe received a visit from Father Joset, who was anxious to explain to him the causes which led to the excitement, and also a slander which the Palouses had invented against himself, that he had furnished the Indians with ammunition. It was then agreed that an interview should be had with the principal chiefs; but only the Coeur d’Alene chief Vincent was found ready to meet Steptoe. In the midst of the interview, which was held as they rode along, the chief was called away and firing was commenced by the Palouses, who were dogging the heels of the command. What at first seemed an attack by this small party of Indians only soon became a general battle, in which all were engaged. Colonel Steptoe labored under the disadvantage of having to defend a pack train while moving over a rolling country particularly favorable to Indian warfare. The column moved, at first, in close order, with the supply train in the middle, guarded by a dragoon company, with a company in the front and rear. At the crossing of a small stream, the Indians closing in to get at the head of the column, Lieutenant Gregg, with one company, was ordered to move forward and occupy a hill which the Indians were trying to gain for that purpose. He had no sooner reached this position than the Indians sought to take possession of one, which commanded it, and it became necessary to divide his company to drive them from the new position.

By this time the action had become general, and the companies were separated, fighting by making short charges, and at a great disadvantage on account of the inferiority of their arms to those used by the Indians. As one of the dragoon companies was endeavoring to reach the hill held by Gregg’s company, the Indians made a charge to get between them and the hill to surround and cut them off. Seeing the movement and its intention, Lieutenant Gaston, who was not more than a thousand yards off, made a dash with his company, which was met by Gregg’s company from the hill, in a triangle, and the Indians suffered the greatest loss of the battle just at the spot where the two companies met, having twelve killed in the charge. 24

Among the killed were Jacques Zachary, a brother- in-law of the Coeur d’Alene chief Vincent, and James, another headman. Victor, an influential chief, also of the Coeur d’Alenes, fell mortally wounded. The rage of the Coeur d’Alenes at this loss was terrible, and soon they had avenged themselves. As the troops slowly moved forward, fighting, to reach water, the Indians kept up a constant raking fire, until about 11 o’clock, when Captain Oliver H. P. Taylor and Lieutenant William Gaston were killed. 25 To these officers had been assigned the difficult duty of flanking the column. Their loss threw the men into confusion, harassed as they were by the steady fire of the enemy, but a few of them gallantly defended the bodies of their officers and brought them off the field under a rain of bullets. 26

It now became apparent that water could not be reached by daylight, and though it was not much past noon, Steptoe was forced to remain in the best position he could obtain on the summit of a hill, on a small inclined plain, where the troops dismounted and picketed their animals. The men were then ordered to lie down flat upon the ground, and do their best to prevent the Indians taking the hill by charges, in which defense they were successful. Toward evening the ammunition, of which they had an insufficient supply, began to give out, and the men were suffering so severely from thirst and fatigue that it was with difficulty the three remaining officers could inspire them to defend themselves. 27 Six of their comrades were dead or dying, and eleven others wounded. Many of the men were late recruits, insufficiently drilled, whose courage these reverses had much diminished, if not altogether destroyed.

Nothing remained now but flight. The deal officers were hastily interred; and taking the best horses and a small supply of provisions, the troops crept silently away at ten o’clock that night and hurried toward Snake River, where they arrived on the morning of the 19th. Thence Steptoe returned to Fort Walla Walla.

One of the reasons, if not the principal one, assigned by the Coeur d’Alenes for their excitability and passion was that ever since the outbreak in 1855 they had said that no white settlements should be made in their country, nor should there be any roads through it; and they were informed a road was about to be opened from the Missouri to the Columbia by the United States government in spite of their protest. 28 They were opposed, also, to troops being sent to Colville, as they said that would only open the way for more troops, and again for more, and finally for the occupation of the country.

General Clarke, learning from Father Joset that the Coeur d’Alenes were penitent, offered to treat with them on easy conditions, considering their conduct toward Colonel Steptoe; he sent their priest back to them with passports, which were to conduct their chiefs to Vancouver should they choose to come.

But the Coeur d’Alenes did not choose to come. True, they had professed penitence to their priest, begging him to intercede for them, but as soon as his back was turned on them, they, with the Spokanes and Kalispels, led by the notorious Telxawney, brewed mischief. The Coeur d’Alenes openly denied consenting to Father Joset’s peace mission, and were incensed that he should meddle with things that did not concern him. After this, attacks on miners and others continued.

In June General Clarke held a consultation of officers at Vancouver, colonels Wright and Steptoe being present, when an expedition was determined upon which should not repeat the blunders of the previous one, and Colonel Wright was placed in command. Three companies of artillery were brought from San Francisco, one from Fort Umpqua, and Captain Judah was ordered from Fort Jones, in California, with one company of 4th infantry. The troops intended for the expedition were concentrated at Fort Walla Walla, where they were thoroughly drilled in the tactics which they were expected to practice on the field, the artillerymen being instructed in light infantry practice, with the exception of a single company, which practiced at artillery drill mounted. No precaution was neglected which could possibly secure discipline in battle.

At the same time that the expedition against the Spokanes and Coeur d’Alenes was preparing, another against the Yakimas was ordered, under the command of Major Garnett, who was to move, on the 15th of August, with 300 troops, northward toward Colville, thus assisting to drive the hostile Indians toward one common center. Before leaving Fort Walla Walla, on the 6th of August, Wright called a council of the Nez Percé, with whom he made a ‘treaty of friendship,’ binding them to aid the United States in wars with any other tribes, and binding the United States to assist them in the same case, at the cost of the government; and to furnish them arms whenever their services were required. The treaty was signed by Wright on the part of the United States, and by twenty-one Nez Perces, among whom were Timothy, Richard, Three Feathers, and Speaking Eagle, but by none of the greater chiefs already known in this history. The treaty was witnessed by six army officers and approved by Clarke 29 A company of thirty Nez Perce volunteers was organized under this arrangement, the Indians being dressed in United States uniform, to flatter their pride as allies, as well as to distinguish them from the hostile Indians. This company was placed under the command of Lieutenant John Mullan, to act as guides and scouts.

On the 7th of August Captain Keyes took his departure with a detachment of dragoons for Snake River, where, by the advice of Colonel Steptoe, fortification was to be erected, at the point selected for a crossing. This was at the junction of the Tucannon with the Snake River. It was built in the deep gorge, overhung by cliff’s on either side, 260 and 310 feet in height. The fortification was named Fort Taylor, in honor of Captain O. H. P. Taylor, killed in the battle of the 17th of May. The place would have afforded little security against a civilized foe, but was thought safe from Indian attack. A reservation of 640 acres was laid out, and every preparation made for a permanent post, including a ferry, for which a large flat-boat was provided.

On the 18th Wright arrived at Fort Taylor, and in a few days the march began. The dragoons numbered 190, the artillery 400, and the infantry 90. The last were organized as a rifle brigade, and armed with Sharpe’s long-range rifles and minié ball, two improvements in the implements of war with which the Indians were unacquainted. On the 31st, when the army had arrived at the head waters of Cheranah River, a point almost due north of Fort Taylor, 76 miles from that post, and about twenty south of the Spokane River, the Indians showed themselves in some force on the hills, and exchanged a few shots with the Nez Percé, who were not so disguised by their uniforms as to escape detection had they desired it, which apparently they did not. They also tired the grass, with the intention of making an attack under cover of the smoke, but it failed to burn well. They discharged their guns at the rear-guard, and retreated to the hills again, where they remained. Judging from these indications that the main body of the Indians was not far distant, and wishing to give his troops some rest before battle, after so long a march, Wright ordered camp to be made at a place in the neighborhood of Four Lakes, with the intention of remaining a few days at that place.

But the Indians were too impatient to allow him this respite, and early in the morning of the 1st of September they began to collect on the summit of a hill about two miles distant. As they appeared in considerable force, Wright, with two squadrons of dragoons commanded by Major W. N. Grier, four companies of the 3d artillery, armed with rifle muskets, commanded by Major E. D. Keyes, and the rifle battalion of two companies of the 9th infantry commanded by Captain F. T. Dent, one mountain howitzer under command of Lieutenant J. L. White, and the thirty Nez Percé under the command of Lieutenant John Hunan, set out at half-past nine in the forenoon to make a reconnaissance, and drive the enemy from their position, leaving in camp the equipage and supplies, guarded by one company of artillery, commanded by Lieutenants H. G. Gibson and G. B. Dandy, a howitzer manned, and a guard of fifty-four men under Lieutenant H. B. Lyon, the whole commanded by Captain J. A. Hardie, the field officer of the day. 30

Grier was ordered to advance with his cavalry to the north and east around the base of the hill occupied by the Indians, in order to intercept their retreat when the foot-troops should have driven them from the summit. The artillery and rifle battalion, with the Nez Perces, were marched to the right of the hill, where the ascent was more easy, and to push the Indians in the direction of the dragoons. It was not a difficult matter to drive the Indians over the crest of the hill, but once on the other side, they took a stand, and evidently expecting a combat, showed no disposition to avoid it. In fact, they were keeping up a constant firing upon the two squadrons of dragoons, who were awaiting the foot-troops on the other side of the ridge.

On this side was spread out a vast plain, in a beautiful and exciting panorama. At the foot of the hill was a lake, and just beyond, three others surrounded by rugged rocks. Between them, and stretching to the northwest as far as the eye could reach, was level ground; in the distance, a dark range of pine- covered mountains. A more desirable battlefield could not have been selected. There was the open plain, and the convenient covert among the pines that bordered the lakes, and in the ravines of the hillside. Mounted on their fleetest horses, the Indians, decorated for war, their gaudy trapping glaring in the sun, and singing or shouting their battle-cries, swayed back and forth over a compass of two miles.

Even their horses were painted in contrasting white, crimson, and other colors, while from their bridles depended bead fringes, and woven with their manes and tails were the plumes of eagles. Such was the spirited spectacle that greeted Colonel Wright and his command on that bright September morning.

Soon his plan of battle was decided upon. The troops were now in possession of the elevated ground, and the Indians held the plain, the ravines, and the pine groves. The dragoons were drawn up on the crest of the bill facing, the plain; behind them were two companies of Keyes’ artillery battalion acting as infantry, and with the infantry, deployed as skirmishers, to advance down the bill and drive the Indians from their coverts at the foot of the ridge into the plain. The rifle battalion under Dent, composed of two companies of the 9th infantry, with Winder and Fleming, was ordered to the right to deploy in the pine forest; and the howitzers, under White, supported by a company of artillery under Tyler, was advanced to a lower plateau, in order to be in a position for effective firing.

The advance began, the infantry moving steadily down the long slope, passing the dragoons, and firing a sharp volley into the Indian ranks at the bottom of the hill. The Indians now experienced a surprise. Instead of seeing the soldiers drop before their muskets while their own fire fell harmless, as at the battle of Steptoe Butte, the effect was reversed. The rifles of the infantry struck down the Indians before the troops came within range of their muskets.

This unexpected disadvantage, together with the orderly movement of so large a number of men, exceeding their own force by at least one or two hundred, 31 caused the Indians to retire, though slowly at first, and many of them to take refuge in the woods, where they were met by the rifle battalion and the howitzers, doing deadly execution.

Continuing to advance, the Indians falling back, the infantry reached the edge of the plain. The dragoons were in the rear, leading their horses. When they had reached the bottom of the hill they mounted, and charging between the divisions of skirmishers, rushed like a whirlwind upon the Indians, creating a panic, from which they did not recover, but fled in all directions. They were pursued by the dragoons for about a mile, when the latter were obliged to halt, their horses being exhausted. The foot-troops, too, being weary with their long march from Walla Walla, pursued but a short distance before they were recalled. The few Indians who still lingered on the neighboring hilltops soon fled when the howitzers were discharged in their direction. By two o’clock the whole army had returned to camp, not a man or a horse having been killed, and only one horse wounded. The Indians lost eighteen or twenty killed and many wounded. 32

For three days Wright rested unmolested in camp. On the 5th of September, resuming his march, in about five miles he came upon the Indians collecting in large bodies, apparently with the intention of opposing his progress. They rode along in a line parallel to the troops, augmenting in numbers, and becoming more demonstrative, until on reaching a plain bordered by a wood they were seen to be stationed there awaiting the moment when the attack might be made.

As the column approached, the grass was fired, which being dry at this season of the year, burned with great fierceness, the wind blowing it toward the troops; and at the same time, under cover of the smoke, the Indians spread themselves out in a crescent, half enclosing them. Orders were immediately given to the pack-train to close up, and a strong guard was placed about it. The companies were then deployed on the right and left, and the men, flushed with their recent victory, dashed through the smoke and flames toward the Indians, driving them to the cover of the timber, where they were assailed by shells from the howitzers. As they fled from the havoc of the shells, the foot soldiers again charged them. This was repeated from cover to cover, for about four miles, and then from rock to rock, as the face of the country changed, until they were driven into a plain, when a cavalry charge was sounded, and the scenes of the battle of Four Lakes were repeated.

But the Indians were obstinate, and gathered in parties in the forest through which the route now led, and on a hill to the right. Again the riflemen and howitzers forced them to give way. This was continued during a progress of fourteen miles. That afternoon the army encamped on the Spokane River, thoroughly worn out, having marched twenty-five miles without water, fighting half of the way. About the same number of Indians appeared to be engaged in this battle that had been in the first. Only one soldier was slightly wounded. The Coeur d’Alenes lost two chiefs, the Spokanes two, and Kamiakin also, who had striven to inspire the Indians with courage, received a blow upon the head from a falling tree-top blown off by a bursting shell. The whole loss of the Indians was unknown, their dead being carried off the field. At the distance of a few miles, they burned one of their villages to prevent the soldiers spoiling it.

The army rested a day at the camp on Spokane River, without being disturbed by the Indians, who appeared in small parties on the opposite bank, and intimated a disposition to hold communication, but did not venture across. But on the following day, while the troops were on the march along the left bank, they reappeared on the right, conversing with the Nez Percé and interpreters, from which communication it was learned that they desired to come with Garry have a talk with Colonel Wright, who appointed a meeting at the ford two miles above the falls.

Wright encamped at the place appointed for a meeting, and Garry came over soon after. He stated to the colonel the difficulties of his position between the war and peace parties. The war party, greatly in the majority, and numbering his friends and the principal men of his nation, was incensed with him for being a peace man, and he had either to take up arms against the white men or be killed by his own people. There was no reason to doubt this assertion of Garry’s, his previous character being well known. But Wright replied in the tone of a conqueror, telling him he had beaten them in two battles without losing a man or animal, and that he was prepared to beat them as often as they chose to come to battle; he did not come into the country to ask for peace, but to fight. If they were tired of war, and wanted peace, he would give them his terms, which were that they must come with everything that they had, and lay all at his feet-arms, women, children-and trust to his mercy. When they had thus fully surrendered, he would talk about peace. If they did not do this, he would continue to make war upon them that year and the next, and until they were exterminated. With this message to his people, Garry was dismissed.

On the same day Polatkin, a noted Spokane chief, presented himself with nine warriors at the camp of Colonel Wright, having left their arms on the opposite side of the river, to avoid surrendering them. Wright sent two of the warriors over after the guns, when one of them mounted his horse and rode away. The other returned, bringing the guns. To Polatkin Wright repeated what had been said to Garry; and as this chief was known to have been in the attack on Steptoe, as well as a leader in the recent battles, he was detained, with another Indian, while he sent the remaining warriors to bring in all the people, with whatever belonged to them. The Indian with Polatkin being recognized as one who had been at Fort Walla Walla in the spring, and who was suspected of being concerned in the murder of the two miners in the Palouse country about that time, he was put under close scrutiny, with the intention of trying him for the crime.

Resuming his march on the 8th of September, after traveling nine miles, a great dust where the road entered the mountains betrayed the vicinity of the Indians, and the train was closed up, under guard, while Major Grier was ordered to push forward with three companies of dragoons, followed by the foot- troops. After a brisk trot of a couple of miles, the dragoons overtook the Indians in the mountains with all their stock, which they were driving to a place of safety, instead of surrendering, as required. A skirmish ensued, ending in the capture of 800 horses. With this booty the dragoons were returning, when they were met by the foot troops, who assisted in driving the animals to camp sixteen miles above Spokane Falls. The Indian suspected of murder was tried at this encampment, and being found guilty, was hanged the same day about sunset.

After a consultation on the morning of the 9th, Wright determined to have the captured horses killed, only reserving a few of the best for immediate use, it being impracticable to take them on the long march yet before them, and they being too wild for the service of white riders. Accordingly two or three hundred were shot that day, and the remainder on the 10th. 33 The effect of dismounting the Indians was quickly apparent, in the offer of a Spokane chief, Big Star, to surrender. Being without horses, he was permitted to come with his village as the army passed, and make his surrender to Wright in due form.

On the 10th the Coeur d’Alenes made proposals of submission, and as the troops were now within a few days’ march of the mission, Wright directed them to meet him at that place, and again took up his march. Crossing the Spokane, each dragoon with a foot soldier behind him, the road lay over the Spokane plains, along the river, and for fifteen miles through a pine forest, to the Coeur d’Alene Lake, where camp was made on the 11th. All the provisions found cached were destroyed, in order that the Indians should not be able, if they were willing, to carry on hostilities again during the year. Beyond Coeur d’Alene Lake the road ran through a forest so dense that the troops were compelled to march in single file, and the single wagon, belonging to Lieutenant Mullan, that had been permitted to accompany the expedition, had to be abandoned, as well as the limber belonging to the howitzers, which were thereafter packed upon mules. The rough nature of the country from the Coeur d’Alene Lake to the mission made the march exceedingly fatiguing to the foot-soldiers, who, after the first day, began to show the effects of so much toil, together with hot and sultry weather, by occasionally falling out of ranks, often compelling officers to dismount and give them their horses.

On the 13th the army encamped within a quarter of a mile of the mission. 34 The following day Vincent, who had not been in the recent battles, returned from a circuit he had been making among his people to induce them to surrender themselves to Wright; but the Indians, terrified by what they had heard of the severity of that officer, declined to see him. However, on the next day a few came in, bringing some articles taken in the battle of the 17th of May. Observing that no harm befell these few, others followed their example. They were still more encouraged by the release of Polatkin, who was sent to bring in his people to a council. By the 17th a considerable number of Coeur d’Alenes and Spokanes were collected at the camp, and a council was opened.

The submission of these Indians was complete and pitiful. They had fought for home and country, as barbarians fight, and lost all. The strong hand of a conquering power, the more civilized the more terrible, lay heavily upon them, and they yielded.

An arbor of green branches of trees had been constructed in front of the commander’s tent, and here in state sat Colonel Wright, surrounded by his officers, to pass judgment upon the conquered chiefs. Father Joset and the interpreters were also present. Vincent opened the council by rising and saying briefly to Colonel Wright that lie had committed a great crime, and was deeply sorry for it, and was glad that he and his people were promised forgiveness. To this humble acknowledgment Wright replied that what the chief had said was true-a great crime had been committed; but since he had asked for peace, peace should be granted on certain conditions: the delivery to him of the men who struck the first blow in the affair with Colonel Steptoe, to be sent to General Clarke; the delivery of one chief and four warriors with their families, to be taken to Walla Walla; the return of all the property taken from Steptoe’s command; consent that troops and other white men should pass through their country; the exclusion of the turbulent hostile Indians from their midst; and a promise not to commit any acts of hostility against white men. Should they agree to and keep such an engagement as this, they should have peace forever, and he would leave their country with his troops. An additional stipulation was then offered-that there should be peace between the Coeur d’Alenes and Nez Percé. Vincent then desired to hear from the Nez Percé themselves, their minds in the matter, when one of the volunteers, a chief, arose and declared that if the Coeur d’Alenes were friends of the white men, they were also his friends, and past differences were buried. To this Vincent answered that he was glad and satisfied; and henceforth there should be no more war between the Coeur d’Alenes and Nez Percé, or their allies, the white men, for the past was forgotten. A written agreement containing all these articles was then for- many signed. Polatkin, for the Spokanes, expressed himself satisfied, and the council ended by smoking the usual peace pipe.

A council with the Spokanes had been appointed for the 23d of September, to which Kamiakin was invited, with assurances that if he would conic he should not be harmed; but he refused, lest he should be taken to Walla Walla. The council with the Spokanes was a repetition of that with the Coeur d’Alenes, and the treaty the same. After it was over, Owhi presented himself at camp, when Wright had him placed in irons for having broken his agreement made with him in 1856, and ordered him to send for his son Qualchin, sometimes called the younger Owhi, telling him that he would be hanged unless Qualchin obeyed the summons. Very unexpectedly Qualchin came in the following day, not knowing that he was ordered to appear, and was seized and hanged without the formality of a trial. A few days later, when Wright was at Snake River, Owhi, in attempting to escape, was shot by Lieutenant Morgan, and died two hours afterward. Kamiakin and Skloom were now the only chiefs of any note left in the Yakima nation, and their influence was much impaired by the results of their turbulent behavior. Kamiakin went to British Columbia afterward, and never again ventured to return to his own land.

On the 25th, while still at the council-camp, a number of Palouses came in, part of whom Wright hanged, refusing to treat with the tribe. Wright reached Snake River on the 1st of October, having performed a campaign of five weeks, as effective as it was in some respects remarkable. On the 1st of October Fort Taylor was abandoned, there being no further need of troops at that point, and the whole army marched to Walla Walla, where it arrived on the 5th, and was inspected by Colonel Mansfield, who arrived a few days previous.

On the 9th of October, Wright called together the Walla Wallas, and told them he knew that some of them had been in the recent battles, and ordered all those that had been so engaged to stand up. Thirty-five stood up at once. From these were selected four, who were handed over to the guard and hanged. Thus sixteen savages were offered up as examples.

While Wright was thus sweeping from the earth these ill-fated aboriginals east of the Columbia, Garnett was doing no less in the Yakima country. On the 15th of August Lieutenant Jesse K. Allen captured seventy Indians, men, women, and children, with their property, and three of them were shot. Proceeding north to the Wenatchee River, ten Yakimas were captured by Lieutenants Crook, McCall, and Turner, and five of them shot, making twenty-four thus killed for alleged attacks on white men, on this campaign. Garnett continued his march to the Okanagan River to inquire into the disposition of the Indians in that quarter, and as they were found friendly, he returned to Fort Simcoe.

Up to this time the army had loudly denounced the treaties made by Stevens; but in October General Clarke, addressing the adjutant-general of the United States army upon his views of the Indian relations in Oregon and Washington, remarked upon the long-vexed subject of the treaties of Walla Walla, that his opinion on that subject had undergone a change, and recommended that they should be confirmed, giving as his reasons that the Indians had forfeited sonic of their claims to consideration; that the gold discoveries would carry immigration along the foothills of the eastern slope of the Cascades; that the valleys must be occupied for grazing and cultivation; and that in order to make complete the pacification which his arms had effected, the limits must be drawn between the Indians and the white race. 35 It was to be regretted that this change of opinion was not made known while General Clarke was in command of the department embracing Oregon and Washington, as it would greatly have softened the asperity of feeling which the opposition of the military to the treaties had engendered. As it was, another general received the plaudits which were justly due to General Clarke.

By an order of the war department of the 13th of September, the department of the Pacific was divided, the southern portion to be called the department of California, though it embraced the Umpqua district of Oregon. The northern division was called the department of Oregon, and embraced Oregon and Washington, with headquarters at Vancouver. 36

General Clarke was assigned to California, while General W. S. Harney, fresh from a campaign in Utah, was placed in command of the department of Oregon. General Harney arrived in Oregon on the 29th of October, and assumed command. Two days later he issued an order reopening the Walla Walla country to settlement. A resolution was adopted by the legislative assemblies of both Oregon and Washington congratulating the people on the creation of the department of Oregon, and on having General Harney, a noted Indian fighter, for a commander, as also upon the order reopening the country east of the mountains to settlement, harmonizing with the recent act of congress extending the land laws of the United States over that portion of the territories. Harney was entreated by the legislature to extend his protection to immigrants, and to establish a garrison at Fort Boise. In this matter, also, he received the applause due as much to General Clarke as himself, Clarke having already made the recommendation for a large post between Fort Laramie and Fort Walla Walla, for the better protection of immigrants. 37

The stern measures of the army, followed by pacificatory ones of the Indian department, were preparing the Indians for the ratification of the treaties of 1855. Some expeditions were sent out during the winter to chastise a few hostile Yakimas, but no general or considerable uprising occurred. Fortunately for all concerned, at this juncture of affairs congress confirmed the Walla Walla treaties in March 1859, the Indians no longer refusing to recognize their obligations. 38 At a council held by Agent A. J. Cain with the Nez Percé, even Looking Glass and Joseph declared they were glad the treaties had been ratified; but Joseph, who wished a certain portion of the country set off to him and his children, mentioned this matter to the agent, out of which nearly twenty years later grew another war, through an error of Joseph’s son in supposing that the treaty gave him this land. 39 The other tribes also signified their satisfaction. Fort Simcoe being evacuated, the buildings, which had cost $60,000, were taken for an Indian agency. A portion of the garrison was sent to escort the boundary commission, and another portion to establish Harney depot, fourteen miles north-east of Fort Colville, 40 under Major P. Lugenbeel, to remain a standing threat to restless and predatory savages, Lugenbeel having accepted an appointment as special Indian agent, uniting the Indian and military departments in one at this post.

General Harney had nearly 2,000 troops in his department in 1859. Most of them, for obvious reasons, were stationed in Washington, but many of them were employed in surveying and constructing roads both in Oregon and Washington, the most important of which in the latter territory was that known as the Mullan wagon-road upon the route of the northern Pacific railroad survey, in which Mullan had taken part. Stevens, in 1853, already perceived that a good wagon road line must precede the railroad, as a means of transportation of supplies and material along the route, and gave instructions to Lieutenant Mullan to make surveys with this object in view, as well as with the project of establishing a connection between the navigable waters of the Missouri and Columbia Rivers. The result of the winter explorations of Mullan was such that in the spring of 1854 he returned to Fort Benton, and on the 17th of March started with a train of wagons that had been left at that post, and with them crossed the range lying between the Missouri and Bitter Root Rivers, arriving at cantonment Stevens on the 31st of the same month. Upon the representation of the practicability of a wagon road in this region, connecting the navigable waters of the Missouri with the Columbia, congress made an appropriation of $30,000 to open one from Fort Benton to Fort Walla Walla. The troubles of the government with Utah, and the Indian wars of 1855-6 and 1858, more than had been expected, developed the necessity of a route to the east, more northern than the route by the South Pass, and procured for it that favorable action by congress which resulted in a series of appropriations for the purpose. 41 The removal of the military interdict to settlement, followed by the survey of the public lands, opened the way for a waiting population, which flowed into the Walla Walla Valley to the number of 2,000 as early as April 1859, 42 and spread itself out over the whole of eastern Washington with surprising rapidity for several years thereafter, attracted by mining discoveries even more than by fruitful soils. 43

Citations:

- At Nathan Eaton’s the defenses consisted of 16 log buildings in a square facing inwards, the object being not only to collect the families for protection, but to send out a scouting party of some size when marauders were in the vicinity. Stevens, in Sen. Ex. Doe., 66, 32, 34th tong. 1st seas.; Ind. Aff. Rept, 34. Fort Henness, on Mound prairie, was a large stockade with blockhouses at the alternate corners, and buildings inside the enclosure. On Skookum Bay there was an establishment similar to that at Eaton’s.[

]

- The northern battalion consisted of Company G (Van Bokelin’s), commanded by Daniel Smalley, elected by the company; Company I, Capt. S. D. Howe, who was succeeded by Capt. G. W. Beam; and a detachment of Company H, Capt. Peabody. Wash. Mess. Gov., 1857, 38-41.[

]

- To I. N. Ebey belongs the credit of making the first movement to blockade the Snoqualimich pass and guard the settlements lying opposite on Whidbey Island. This company of rangers built Fort Ebey, 8 miles above the mouth of the Snohomish River. He was removed from his office of collector, the duties of which were discharged by his deputy and brother, W. S. Ebey, during the previous winter while he lived in camp, through what influence I am not informed. M. H. Frost of Seattle was appointed in his stead. This change in his affairs, with the necessity of attending to private business, probably determined him to remain at home. George W. Ebey, his cousin, was 23 Lieut in Smalley’s company.[

]

- The central battalion was composed of Company B, Capt. A. B. Rabbeson; Company C, Capt. B. L. Henness’ mounted rangers; a train guard under Capt. O. Shead; the pioneer company under Capt. Joseph A. White, 1st Lieut Urban E. Hicks; and Company F, a detachment of scouts under Capt. Calvin W. Swindal. Wash. Mess. Gov., 1857, 28.[

]

- The southern battalion consisted of the Washington Mounted Rifles, Capt. H. J. G. Maxon, Company D, Capt. Achilles, who was succeeded by Lieut Powell, and two Oregon companies, one company, K, under Francis M. P. Goff, of Marion County, and another, Company J, under Bluford Miller of Polk County. Oregon Statesman, March 11 and May 20, 1856.[

]

- Southern Battalion of Washington[

]

- Rept of Major Hays, in Wash. Mess. Gm , 1857, 290-2.[

]

- Second Regiment of Washington Volunteers[

]

- See letters of W. H. Pearson and other correspondents, in Oregon Statesman, Aug. 5, 1856; Oregon Argus, Aug. 2, 1856; Olympia Pioneer and Dem., Aug. 5, 1856. Pearson, who was in the Nez Perce country, named the hostile chiefs as follows: Looking Glass, Three Feathers, Red Bear, Eagle-from-the-light, Red Wolf, and Man-with-a-rope-in-his-mouth.[

]

- Old Fort Walla Walla of the H. B. Co. being abandoned, the name was transferred to this post, about 28 miles in the interior.[

]

- Olympia Pioneer and Dem., Nov. 28, 1856; Elridge’s Sketch, MS., 9.[

]

- Olympia Pioneer and Dem., July 3 and Dec. 11, 1857.[

]

- Patkanim died soon after the war was over. The Pioneer and Democrat, Jan. 21, 1859, remarked: ‘It is just as well that he is out of the way, as in spite of everything, we never believed in his friendship.’ Seattle died in 1866, never having been suspected. Kussass, chief of the Cowlitz tribe, died in 1876, aged 114 years. He was friendly, and a Catholic. Olympia Morning Echo, Jan. 6, 1876.[

]

- Deady’s Hist. Oregon, MS., 35; Grover’s Pub. Life, MS., 59; Oregon Statesman, Oct. 20, 1857, and March 30 and April 6, 1858; H. Ex. Doc., 45, pp. 1-16, 35th cong. 1st sess. The exact footing was $4,449,949.33 for Oregon; and $1,481,475.45 for Washington $5,931,424.78. Of this amount, the pay due to the Oregon volunteers was $1,400,604.53; and to the Washington volunteers $519,593. 06.[

]

- Said Horace Greeley: `The enterprising territories’ of Oregon and Washington have handed into congress their little bill for scalping Indians and violating squaws two years ago, etc., etc. After these [the French Spoliation claims] shall have been paid half a century or so, we trust the claims of the Oregon and Washington Indian-fighters will come up for consideration.’ New York Tribune, in Oregon Statesman, Feb. 16, 1858.[

]

- On the Oregon war debt, see the report of the third auditor, 1860, found in H. Ex. Doc., 11, 36th cong. 1st sess.; speech of Grover, in Cong. Globe, 1858-9, pt ii., app. 217, 35th cong. 2d sees.; letter of third auditor, in H. Ex. Doc., 51, vol. viii. 77, 35th cong. 2d sess.; Statement of the Oregon and Washington delegation in regard to the war claims of Oregon and Washington, a pamphlet of 67 pages; Dowell’s Scrap-Book of authorities on the subject; Oregon Jour. Sen., 1860, app. 35-G; Dowell’s Or. Ind. Wars, 138-42; Jessup’s Rept on the cost of transportation of troops and supplies to California, Oregon, and New Mexico, 2; rept of commissioner on Indian war expenses in Oregon and Washington, in H. Ex. Doc., 45, 35th cong. 1st seas., vol. ix.; memorial of the legislative assembly of 1855-6, in H. Misc. Doc., 77, 34th cong. 1st sees., and H. Misc. Doc., 78, 34th cong. 1st sess., containing a copy of the act of the same legislature providing for the payment of volunteers; report of the house committee on military affairs, June 24, 1856, in H. Rept, 195, 34th cong. 1st sees.; reports of committee, vol. i., H. Rept, 189, 34th cong. 3d sess., in H. Reports of Committee, vol. 3; petition of citizens of Oregon and Washington for a more speedy and just settlement of the war claims, with the reply of the third auditor, Sen. Ex. Doc., 46, 37th cong. 2d sees., vol. v.; Report of the Chairman of the Military Committee of the Senate, March 29, 1860; Rept Com., 161, 36th cong. 1st sess., vol. i.; communication from Senators George H. Williams and W. H. Corbett, on the Oregon Indian war claims of 1855-6, audited by Philo Callender, which encloses letters of the third auditor, and B. F. Dowell on the expenses of the war, Washington, March 2, 1868, in H. Misc. Doc., 88, p. 3-10, ii., 40th cong. 2d sess.: report of sen. corn. on interest to be allowed on the award of the Indian war claims, in Sen. Corn. Rept, 8, 37th cong. 2d sess.; letter of secretary of the treasury, containing information relative to claims incurred in suppressing Indian hostilities in Oregon and Washington, and which were acted and reported upon by the commission authorized by the act of August 18, 1856, in Sen. Ex. Doe., 1 and 2, 42d cong. 2d sess.; report of the committee on military affairs, June 22, 1874, in H. Repts of Corn., 873, 43d cong. 1st sess.; letter from the third auditor to the chairman of the committee on military affairs on the subject of claims growing out of Indian hostilities, in Oregon and Washington, in H. Ex. Doc., 51, 35th cong. 2d sess.; vol. vii., and H. Doc., vol. iv., 36th cong. 1st sess.; communication of C. S. Drew, on the origin and early prosecution of the Indian war in Oregon, in Sen. Misc. Doc., 59, 36th cong. 1st sess., relating chiefly to Rogue River Valley; Stevens’ Speech on War Expenses before the Committee of Military Affairs of the House, March 15, 1860; Stevens’ Speer on War Claims in the House of Representatives, May 31, 1858; Speeches of Joseph Lane in the House of Representatives, April 2, 1856, and May 13, 185 ; Speech of I. I. Stevens in the house of Representatives, Feb. 31, 1859; Alta California, July 4, 1857; Oregon Statesman, Jan. 26, 1858; Dowell and Gibbs’ Brief in Donnell vs Cardwell, Sup. Court Decisions, 1877; Early Affairs Siskiyou County, MS., 13; Swan’s N. TV. Coast, 388-91.[

]

- See a list by S. C. Drew, in the N. Y. Tribune, July 9, 1857. Lindsay Applegate furnishes a longer one, but neither list is at all complete. See also letter of Lieut John Mullan to Commissioner Mix, in Mutton’s Top. Mem., 32; Sen. Ex. Doc., 32, 35th cong. 2d sess.[

]

- I arrived at this estimate by putting down in a book the names and the number of persons murdered or slain in battle. The result surprised me, although there were undoubtedly others whose fate was never certainly ascertained. This only covers the period which ended with the close of the war of 1855-6; there were many others killed after these years.[

]