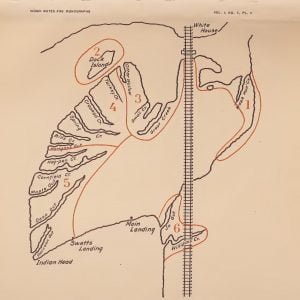

Of the remnant tribes in Virginia, the Pamunkey have long formed the social backbone. They have retained their internal government, their social tradition and geographical position as the people of Powhatan. Their village is one mile from the station of Lester Manor, about twenty miles east of Richmond. It comprises an area of some three hundred acres almost surrounded by a curve of the Pamunkey River. Much of it is a virgin swamp which constitutes the tribal hunting ground. As their village was the capital in Indian days, the Pamunkey under Powhatan figured most prominently in the events connected with the founding of Jamestown and the explorations by Captain John Smith. Even after the disastrous but inevitable wars of 1622 and 1644 in which the Powhatan tribes were cut to pieces by English gunpowder and steel, the Pamunkey still preserved their integrity as a tribe and exacted a deed for their reservation from the Virginia assembly in 1677.

This treaty is recorded in the Acts of the General Assembly of Virginia. The present chief and council retain a copy of it, which is quoted in the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (vol. v, pp. 189-195). It explicitly mentions the rights of the Indians, permitting “oystering, fishing, gathering tuckahoe, curtenemmons, 1 wild oats, rushes, and puckwone.'” The treaty also alludes to the return of white children and slaves among the Indians and forbids any further enslavement of Indians. There are known to have been subsequent records of dealings with the Indians preserved in the archives of King William Court House; but these were destroyed at the time when, during the Civil War, the court house was burned by the Northern troops and the records in the clerk’s office lost.

Thus having secured a home right to reside in their old domains, the tribe settled down under its own rulership, where it may still be found. The reservation population has for a considerable time approximated 150 souls. The Indians on the Mattaponi River, only about ten miles from the Pamunkey, appear to have been closely affiliated with the Pamunkey, and the recent history of the two bands has been practically identical. There are about 75 in the Mattaponi village near Wakema; they are completely merged in blood with the Pamunkey, through inter-marriage, and no differences in community life can be observed between them. The Mattaponi are also reservation Indians; their deed, in the possession of the chief, dates also to 1658. The two preceding bands are the only “reservated Indians,” as they quaintly style themselves, in the state. Types of the group appear in figs. 1-14 in the gallery below.

The interesting band of Pamunkey Indian descendants has been persistently ignored by serious investigators for reasons which are obvious but not good. Dwelling on their own land continuously since their complete defeat about 1676, the remnants have kept up their tribal organization and to a degree their economic life without interruption or interference, although they have lost entirely their language, their social and ceremonial culture. The little group has numbered about 150 souls for many years with-out much change, as mentioned. Had they, how-ever, been able to keep together without the young men having to emigrate to the cities to find employment, the number would now be much larger. Many have married outside of the tribe and moved away, for Pamunkey law allows a man of the tribe to bring his alien wife to the reservation, but a girl who marries an outsider has to depart and reside off the reservation. Moreover, any Pamunkey individuals who leave the town for two years with-out returning, be it only for a short time, forfeit their privileges as tribal members. Hence the Pamunkey, like the other surviving units of Virginia, are not dying out, but being absorbed in the general population. Such a process is for sentimental reasons unfortunate, but it is Inevitable.

The loss of the native language among all the Virginia remnants has been complete. Save for half a dozen words or so, mostly names of local flora and fauna, nothing remains. This situation is comparable to cases elsewhere in the East, such as that of the Huron of Lorette, Province of Quebec, whose tongue has succumbed to French; the Algonkian (Algonquian) remnants in southern New England, and the Catawba of South Carolina, all of whom now speak only English. One might be inclined to suspect that such a condition is associated in some way with Negroid miscegenation were it not for the instance of the Huron-Iroquois of Quebec, whose mixture has been almost exclusively with the French. The only linguistic material we now possess, and this is only in glossaries except for half a dozen short sentences, is to be found in Smith’s narrative and in Strachey’s History of Virginia. Since those times only some isolated words of questionable origin have been recorded from the Pamunkey by Dalrymple and from Nansamond by Mooney. At Chickahominy a short list of terms was given me several years ago. Most of them, however, proved to be Ojibwa.

Among the Pamunkey a few native practices of great interest have been preserved from the past. They distribute their time between farming, fishing, and hunting. They raise the original native crops, they haul seine and trawl lines, and pursue deer, raccoons, and wild turkeys and other wild fowl on their famous river, and maintain their hunting territories for the taking of fur and meat in the primeval swamp forming part of their reservation. Native snares and dead fall traps still compete with modern methods of taking game. Only within the last twenty years have the hunters abandoned the use of the log dugout pirogue, though one may still be seen.

Of native arts the Pamunkey have preserved the manufacture of their distinctive clay pots and pipes, and have even preserved that egregious technique, turkey-feather knitting, as well as declining phases of basketry and bead working. And tribal government continues. Some dances and costume performances of a social and carnival character are part of their tradition.

Pamunkey Photo Gallery

Citations:

- The term curtenemmons refers to the dock-plant growing on the river. In Chickahominy the word is cutlemon an interesting dialectic variation, if the word is not per-chance a derivation from English “cut-lemon,” which the pod actually resembles.[

]