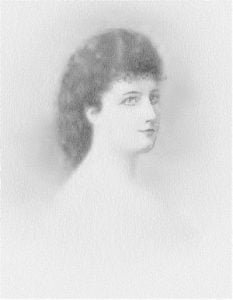

(Mrs. Hughes-Hallett)

From portrait by Waugh

Every Philadelphia girl who has hoped to be a belle during this last quarter of the century, and even many who have been without social aspirations, have been brought up on traditions of Emilie Schaumburg.

Yet so eminent was the place she held in the old city whose standard of belleship had been fixed far back in the colonial days of America, that no one has ever succeeded her.

Accustomed through long generations to women of wit, beauty, and a certain unapproachable taste in matters of personal adornment, Philadelphia has developed a critical instinct which is not easily satisfied

“The ladies of Philadelphia,” wrote Miss Rebecca Franks over a century ago, “have more cleverness in the turn of an eye than those of New York have in their whole composition. With what ease have I seen a Chew, a Penn, an Oswald, or an Allen, and a thousand others, entertain a large circle of both sexes; the conversation, without the aid of cards, never flagging nor seeming in the least strained or stupid. Here, in New York, you enter the room with a formal set courtesy, and, after the howdos, things are finished; all is dead calm till the cards are introduced, when you see pleasure dancing in the eyes of all the matrons, and they seem to gain new life.”

It is but just to state that this fair critic of New York’s social status belonged to Philadelphia, where, though her wit was rather of a satirical turn, she was noted as a lady possessed of “every human and divine advantage.” She was the youngest of the three daughters of David Franks, one of whom became the wife of Oliver de Lancey, another of Andrew Hamilton, of “Woodlands,” one of the famous suburban estates of the city, while Rebecca, “high in toryism and eccentricity,” after an unusually brilliant belleship, bestowed her hand on Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Johnston, and went to live in England.

Of the Chews referred to in her letter from New York, so sparkling was the conversation which Harriet could maintain, that Washington, when he was sitting for his portrait to Stuart, liked to have her in the room that his face might wear its most agreeable expression, such as her wit always induced. She married the son of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the young Charles Carroll who was at one time suspected of having a tender interest in Nellie Custis, Washington’s step-granddaughter. Her sister Margaret, who was one of the beauties who made the great feast of the Mischianza so famous, also married a son of Maryland, Colonel John Eager Howard, a patriot and a hero. Passing through her room one evening he heard her relating to her children the pathetic story of Major Andre, who had been her knight in the tournament of the Mischianza.

“Don’t believe a word of it, children,” he interrupted, as their young hearts swelled with pity at her graphic and romantic recital; “he was an infernal spy.”

Ann Willing, who married William Bingham in her seventeenth year, was another woman who helped to establish the standard of female beauty and excellence in Philadelphia. “She is coming quite into fashion here,” John Adams’s daughter wrote of her from London, “and is very much admired. The hair dresser who dresses us on court days inquired of mamma whether she knew the lady so much talked of here from America, Mrs. Bingham. He had heard of her from a lady who had seen her at Lord Duncan’s.”

London society, and especially that of the court circle, was not very favorably disposed towards Americans in the year 1786, and the subsequent graciousness of their reception they doubtless owed largely to the impression created by the beauty and character of such a woman as Mrs. Bingham, who was one of the first to seek a presentation at the court of George III after our separation from the mother country. Her striking beauty of face and form, her easy deportment, that had all the pride and grace of high breeding, the intelligence of her countenance, and the entire affability of her attitude disarmed every feeling of unfriendliness and converted every one, said Mrs. Adams, into admiration.

The unfortunate Margaret Shippen, as gifted as she was beautiful, deprived by her husband’s treason before she was twenty years old of the shelter of her home and the protection of her family, the Executive Council of Pennsylvania bidding her to leave the State and not return till the close of the war, and Sarah, the daughter of Benjamin Franklin and wife of Richard Bache, and the embodiment of Republican principles, which caused her to insist that there was “no rank in America but rank mutton,” are two noted examples of that diversity which gave flavor to the social life of a city that has tempted the pens of both native and foreign critics.

Philadelphia was one of the first of the Northern cities to admit women to the pit of its theatres, and visitors from quiet Boston and commercial New York at one time condemned its social tone as fast, because its young men gave wine-suppers, and because it danced to the music of a full colored orchestra, known as Johnson’s Band, while other cities were performing their more or less graceful gyrations to the tunes furnished by one or two musicians.

The Quaker town had made a brilliant social record before many of the cities of America had so much as laid one stone upon another. By comparison it is old. It has its elements of newness, like all bodies that grow and progress, but they are not readily assimilated by that little coterie that long ago laid the foundation of its establishment in the southeastern section of the city. It is from the predominance of this conservative social principle in Philadelphia that people unfamiliar with its life have derived the erroneous impression that its general progress and development have been correspondingly deliberate.

To hold such a position as Emilie Schaumburg held in Philadelphia implies the possession of such personal qualities and such gifts as would be an open door to the most exclusive society of the world.

She was well born, coming of ancestry distinguished both in their native land and in that of their adoption. Her grandfather, Colonel Bartholomew Schaumburg, belonged to one of the oldest families in Germany. He was a godson and ward of the Landgrave Frederick William, with whom he was closely connected. When still quite a youth, the Landgrave made him an aide-de-camp to Count Donop, who commanded the Hessian subsidies furnished by Germany to England to aid her in the war with the American colonies.

Schaumburg was sent with despatches to Donop, who, however, had been killed before the arrival of his young aide-de-camp. Learning for the first time of the righteousness of the American cause, he gallantly offered his services to the commander-in-chief of the American forces. He fought valiantly all through the war, and at its close accepted a commission in the standing army organized by the new government. At the Cotton Centennial held at New Orleans in 1884, his commissions signed by Washington were exhibited and were objects of much interest. He took part in many of the early Indian wars, and was appointed quartermaster-general in the war of 1812.

His home was at New Orleans. His eldest daughter, at the time of General Lafayette’s visit to that city, was one of the twelve young girls selected on account of their beauty from its most distinguished families to crown America’s friend. She lived to an advanced age, surviving her eleven companions of that memorable occasion and retaining much of her beauty till the close of her life.

The site of the city of Cincinnati was indirectly chosen by Colonel Schaumburg when he selected the spot where it later sprung up for the establishment of a fort, which he called, in honor of his first American friend, Fort Washington.

He was an accomplished artillerist, and under his direction was cast the first cannon made in the United States. While stationed in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, upon military duty, he met the lady whom he afterwards married, and who had not long previously arrived in America, whither she had come with her parents to trace a recent acquisition of land.

She was a lineal descendant of the principal Indian chief, Secaneh, of the Lenape tribe, who signed the treaty of 1683 with William Penn, selling him the large tract of land on which Philadelphia is built.

The Princess Susahena, the daughter of Secaneh, had been married to Thomas Holme McFarlane, a nephew of Thomas Holme, who was the first Surveyor-General of Pennsylvania. Three years after their marriage they sailed for Dublin, but ocean voyages in those days were trials to the stoutest constitutions, and the poor princess died before reaching the other side.

Her child, a daughter, lived, and it was the great-granddaughter of this child who became the wife of Colonel Schaumburg, so that Emilie Schaumburg is the seventh generation in lineal descent from the aboriginal princess, and attained her remarkable social queen ship on the native heath of her royal ancestors.

Mrs. Henry D. Gilpin, who had known Colonel Schaumburg’s family intimately and had spent much time with them in their Southern home, frequently spoke of the great beauty of Emilie Schaumburg’s grandmother, and of the resemblance Emilie bore to her. She had the fresh Irish complexion and violet eyes, together with suggestions of the Indian type of her ancestry in the tall, lithe figure, delicately aquiline features, and black hair, which almost swept the ground.

They were a strikingly handsome couple, for Colonel Schaumburg was as magnificent in appearance as he was conspicuous in courage. He was several inches over six feet in height, and clung all his life to powdered hair and lace ruffles, those outward signs of the aristocrat; yet he adopted republican principles, dropped his title, and besought his children to be satisfied with the record he should leave them of services rendered his adopted country.

He had declined the overtures made him by his family in Germany, from whom he had become estranged owing to the course he had pursued in espousing the American cause. He had no desire to return and resume his career there.

When his granddaughter, however, visited Germany she was received with marked consideration by the Princess of Schaumburg Lippe, who was reigning at the time.

True to his principles, Colonel Schaumburg opposed the formation of the Society of the Cincinnati, refusing to become a member of it, and arguing that it had for its object the inauguration of an aristocracy, and was in direct opposition to the very principles for which they had fought.

His son followed in his footsteps in selecting a military career. He was graduated from the National Military Academy in 1833, and entered the cavalry. He was a gallant officer, generous and impetuous, and as magnificent in physique as his father.

He lost his commission through a technicality which the War Department turned to his disadvantage, and fought all his life for reinstatement, being upheld by President Jackson and a majority of the United States Senate.

He had imbibed his father’s ideas, and would never use the “von” in his name because his father had dropped it. When his daughter wished to resume it, however, he gave his consent and approval.

Major Schaumburg married a daughter of Stephen Page, originally of Page County, Virginia, and later of Eden Park, a beautiful country seat, near Philadelphia, where his children were born. Miss Page, who became Mrs. Schaumburg, was a woman of much beauty and many accomplishments, which she transmitted to her daughter.

Emilie von Schaumburg grew up in the home of her uncle, Colonel James Page, with whom her name is ever identified. Though he was a man of social and political prominence, his greatest distinction, in the eyes of his fellow citizens, arose from his relationship to her.

When this new fame dawned upon him, he had been for nearly fifty years a well-known and popular figure in the life of the city. His military record had been made in his youth during the war of 1812. He had been Postmaster and Collector of the Port of Philadelphia, a leader in Councils, County Treasurer in an era when politics had gone hand in hand with principle and patriotism. He was a Jacksonian Democrat, and had come to be looked upon as the grand old man of his party, who by birth and breeding could adorn a ball at Madam Rush’s or make an after dinner speech with as ready a grace as he could march at the head of the State Fencibles.

In no capacity, however, did he attract that peculiar interest that pursued him whenever he appeared in public with his niece. On winter afternoons, at a time when that season was rather longer in the Middle States than it is at the close of the century, and when the waters of the rivers used to remain fast frozen for many days they frequently appeared among the skaters, of whom, in his youth. Colonel Page had been one of the celebrities. He found new enthusiasm in the graceful sport, however, from the admiration he read in all faces whenever he went upon the ice with his niece.

They formed a picture that many paused to look upon, while others, who knew nothing of the intricacies of the accomplishment, gathered on the river bank solely for the pleasure of watching them as they took those wonderfully long, sweeping curves of the “outer edge,” the lithe figure of the girl seeming to float like a bird on the wing, while the splendid poise of the handsome, vigorous old man was as erect, as easy, and as firm as in his youth. He always held that the highest art in skating was in perfecting, to an almost incredible degree, the delicate balance of the body on the outer edge of the skate, and so broadening and lengthening the curves, which are ever, according to Hogarth, the lines of beauty. The result justified the theory, and he found an apt pupil in his niece, whose skating, like her dancing, was the very poetry of motion.

The beauty of some women admits of a diversity of opinion. Emilie von Schaumburg’s did not. It was absolute, and the effect was instantaneous. A head of classic mould, with its rich adornment of lustrous black hair, proudly poised upon a throat and shoulders of perfect form; an oval face, lighted with a fine vivacity and captivating smile; great hazel eyes with dark brows and sweeping lashes; delicate, regular features, and a complexion which no art could imitate in its transparent fairness and brilliancy; a figure, tall and svelte, all undulating lines and willowy grace; a regal carriage, and, above all, an air of high bred elegance and distinction; such, in her early girlhood, was Emilie von Schaumburg, whom the Prince of Wales declared the most beautiful woman he had seen in America.

It was on that famous night when the visit of His Royal Highness to the Academy of Music brought thither one of the most distinguished audiences ever assembled in Philadelphia. She was dressed with girlish simplicity in white, her only ornament being a small chain of golden sequins, which bound the rich masses of her hair and defined her shapely head, yet such was the subtle power of her presence, that from the moment she entered that crowded assembly, with its tier upon tier of brilliantly arrayed women, she became the focus of all eyes, dividing the attention of the Prince of Wales and the audience with Patti, who was pouring out her soul in matchless melody upon the stage.

One night, a few years ago, during a performance of Madame Bernhardt, in Philadelphia, a woman occupying one of the boxes, and carrying herself with that fine spirit that had been the glory of a previous generation, was recognized as Emilie Schaumburg, for so she still is, and forever will be known, among the people of her own city and country.

The discovery flew from mouth to mouth, and many who had never before seen her, as well as those who looked upon her for the first time after many years, and recalled that memorable night at the Academy of Music, bent upon her a gaze of unmistakable admiration.

Her education was principally directed by Hon. Henry Gilpin, who was the Attorney-General of Van Buren’s administration, and a most finished scholar.

To the many advantages she enjoyed in having access to his library she subsequently added a thorough knowledge of several modern languages, for her intellectual endowments were in no degree inferior to her physical gifts. Though she had a fine artistic sense and an almost incredible facility in the acquirement of knowledge, she yet early recognized the necessity of serious study and intelligent application.

In this recognition and the ability to comply with its requirements, perhaps, more than in any other thing lies the vast difference between the mere butterfly of society and the woman who leaves the impress of her individuality upon the life in which she moves.

Emilie Schaumburg never attempted a thing for which she had no special talent, but, having once undertaken a study, she pursued it with enthusiasm, following its every detail to the limit of her capacity. To an admirer, who once exclaimed, ” Is there anything in the world you cannot do, and do brilliantly?” she replied, “Yes: I was a dismal failure at both sewing and arithmetic.”

Her voice, in speaking as in singing, lent itself to every delicate inflection. She would delight, when still a very young child, to imitate. Each new song she caught with an unerring ear, the florid passages, roulades, and trills flowing as easily and naturally from the childish throat as from that of a bird. This marvelously flexible quality of voice she has never lost. In speaking of her musical education, she once said to a friend, “I have had to study phrasing and style and expression, with sostenuto, crescendo, diminuendo, and various other artistic effects, but the drudgery of exercises was spared me, thanks to my fairy godmother.”

She has always retained her habits of study, and even during her first brilliant season in Paris she found time to take lessons from Madame La Grange and also from the celebrated teacher Delle Sedie. Later, however, at Nice, she studied more consecutively with Maestro Gelli, who recognized the unusual order of her talents and wrote several beautiful morceaux expressly for her.

Her beauty and accomplishments were the open sesame to the exclusive circles of the villa society at Nice, and among the many distinguished people whom she delighted with her rare gifts was the late lamented Duke of Albany. Like most of the royal family of England, he was an accomplished critic and an ardent lover of music. He was enthusiastic in his praise of Miss von Schaumburg’s singing, and when she again met him, a year or two later, at a court-ball at Buckingham Palace, his greeting proved that he had not forgotten the impression it had made upon him. His first words were, “And how is the beautiful voice?”

Before she left Philadelphia her histrionic talents had perhaps made her more widely known than any other of her many accomplishments. During the war for the Union, when the stage was the means of raising many dollars for the benefit of the wounded and suffering soldiers, she was foremost among the bright and spirited society women who devoted their talents to the cause.

Her dramatic success was due neither to her beauty nor to her personal charm, though her expressive features, her voice, and her perfect grace and ease were undoubtedly powerful adjuncts. Her triumphs were legitimate, and were the result of careful study, artistic finish, and unusual histrionic ability. That she possessed, in an extraordinary degree, the power of getting out of herself and into her parts was evidenced by the tribute contained in the criticism of some friends who went to see her in “Masks and Faces.”They had gone, they said, solely to see Miss Schaumburg, whom, however, they soon forgot, their interest becoming absorbed in the brilliant, fascinating, impulsive Peg.

Yet Emilie Schaumburg was a very young girl when she stepped upon the amateur stage of the Seventeenth Street Drawing Room, and had never had a lesson in declamation nor a suggestion from any one to help her in the study of her parts. To be able to forget one’s identity, and to make one’s audience forget it is, after all, the acme of high art in acting, or, rather, it is the touch of genius which is above art, since it cannot be taught.

As Peg Woffington in “Masks and Faces,” and as the Countess in the “Ladies’ Battle,” she carried conservative and critical audiences by storm. Ristori, who was present at one of the performances, expressed unqualified admiration at the high order of Miss Schaumburg’s talent, for both roles are considered tests to trained actresses.

She scored another success in the little operetta, “Les Noces de Jeannette,” which she sang and acted in French, and in which the piece de resistance is the great air du rossignol. There are many people in Philadelphia today who yet recall the brilliancy and daring of those tours de forces between the voice and the flute, each one in turn taking up the refrain and soaring higher and higher in imitation of the nightingale; yet there was never a harsh or strained note in her perfect voice, but all as liquid, pure, and full-throated as the warbling of the veritable bird.

Another of the gifts she possessed was for verification. She brought it into frequent and graceful play, but only for the enjoyment of those who were admitted to the privilege of an intimate friendship with her.

It is little wonder that Emilie von Schaumburg should have made an impress upon the city of her nativity which has remained proof against time and absence. No woman ever won a more spontaneous admiration than fell to her lot. She never appeared upon the streets that she was not surrounded and followed by both men and women, who, frequently without knowing her came simply to look upon her beauty and glory in her possession.

She married, in England, Colonel Hughes-Hallett, of the Royal Artillery, and member of Parliament for Rochester. She resides now during the greater part of the year at Dinard, in France, where she built, some years ago, the beautiful chateau of Montplaisir.

Still a strikingly handsome and distinguished woman, she gathers about her the aristocracy of both France and England as well as the most eminent and charming of her compatriots. She entertains during each season with that same graciousness of hospitality with which she once presided in her uncle’s home in Philadelphia.

She recently added a ballroom to Monplaisir which she inaugurated by a series of concerts and balls, among the picturesque features of the latter being minuets, gavottes, and a cotillon.

Gowned in a white and silver brocade Watteau, with panniers, over a pink satin petticoat trimmed with flounces of old lace, headed with wreaths of roses of a deeper pink, her powdered hair crowned with a black Gainsborough hat with black, white, and pink plumes, Mrs. Hughes-Hallett took part in one of the stately gavottes, making a beautiful picture against the delicate blue background and Louis Quinze decorations of her artistic ballroom.

A life filled with adulation, that would have been the undoing of a less wise woman, has in no way impaired her charm of character. Her fine mental poise, her exquisite humor, together with the generosity and sweetness of her nature, have preserved her from that calamitous sense of satiety that has overtaken many a man and many a woman who have lost their balance completely in an altitude of admiration much below that in which Emilie von Schaumburg has passed her life.