Picture writing was the earliest form of the notation of ideas adopted by mankind. There can be little question that it was practiced in the primitive ages, and that it preceded all attempts both at hieroglyphic and alphabetic writing. It is impossible to think of a time when man had not the faculty and disposition to draw a figure. The very power of imitation, implanted in the mind, implies it. The first track of an animal on the sand, the very shadow of a tree on the plain, would suggest it. The figure of an animal would be the symbol for the animal; and that of a man, for a man. A bow or a spear drawn in the hand of the latter would be the natural symbol for an act. Thus actual objects, and actual deeds, past or future, would at once be symbolized. Was man ever in a condition not to accomplish this? Even supposing that he was created a barbarian, and not a civilized or industrial being, which would be adverse to all sacred authority, he would not long wait to compass this simple attainment. Here, then, is the first element of transmitting thought. A bow and arrow, a spear and club, a sword and javelin, were no sooner made than they were employed as symbols of acts: for next to action itself, is the desire of perpetuating the remembrance of the act, however rudely or imperfectly it may be done.

All arts and inventions are but the monuments of pre-existing thought. They embody, in wood, iron, or other materials, forms which had been pre-conceived, and thus depict the involutions and inventions of the mind. There is nothing new in this general principle of depicting objects, whether it be done by pigments, or represented in the solid realities of wood or stone. The mind itself, so far as related to its natural powers, was as fully endowed with the power of induction and analogy in the first, as in the last ages; and those are quite mistaken, who, with respect to the common arts and wants of life, suppose that the earlier ages were lacking in ingenuity. Industrial labors were performed with far more perfection at an early day than is generally supposed, as all must admit who have searched into the history and antiquity of cutting gems, of mosaics, pottery, metallurgy, and other early-noticed arts. How far representations by pictures and figures kept pace with inventions, we are left in a great measure to infer. We only perceive that some of the elements of a pictorial system were very ancient. Idolatry itself had its rise in this system, and it is only from the denunciations on this head, contained in the Scriptures, that we are historically apprized of the early existence of the art, both in its form of images and of symbolic devices.

One of the most obvious devices of the primitive ages, in picture-writing, would appear to have been to leave a personal device or mark, to stand as the sign of a name; and hence we see that seals and “signets” were used long before letters. 1 To mark public transactions, heaps of stones were erected. This was probably the type and origin of the rage for pyramids, to which the early nations so long directed their efforts, and by which they sought to perpetuate their fame and the memory of their power. It is owing, indeed, to this trait of raising massive structures of earth and stone, towering to the skies, that we owe the preservation of our best and most ancient evidences of the pictorial, hieroglyphic, and inscriptive arts. Traces of these arts are found on the oldest existing monuments in the world. Outlines of animals, and things rudely drawn, are yet to be seen on the bricks of Babylon. The valley of the Nile is replete with evidences of the more advanced stages of this art, in which the simple pictorial gave way to the true hieroglyphic, and finally to the phonetic. Among the most ancient forms of inscription, which are now proved to have been provided with an alphabetic key, the ancient arrow-headed character of Persia may be adduced. German research has mastered, so far as the subject permits, the inscriptions of the Mokah-Wadey, near Mount Sinai. Important advances have been made in the recovery of the Etruscan language and alphabet. The gradation between a heap of stones, a barrow, a mound, a teocalli, and a pyramid, are not more marked as connected links in the rise of architecture, than are a representative figure, an ideographic symbol, a phonetic sign, and an alphabetical symbol, in the onward train of letters.

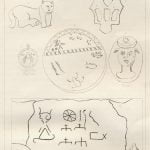

But however symbols and figures may have connected their existence with the early monuments of mankind, there is no branch of the representative or pictorial art in which they led to such deplorable moral results, as in the form and expression which these figures anciently gave to idolatry. If letters may be called the language of Christianity, picture writing is emphatically the language of idolatry. It filled the human mind with gross material objects of veneration. It put the shadow for the substance; and having given distinct form to the idea of a deity, the devotee was not long in attributing to the form all power and honor that pertained to the deity itself. Every class of nature put in its claims as the representative of God; and it is no wonder that a calf, a plant, an insect, a bird, and other images were employed. Two of the most ancient forms of this kind are found in the following representations of Baal, and the Egyptian Fly-God, both of which are taken from ancient coins. (See Plate 66, Figures 3 and 5.)

Man had but just emerged from the hands of his Creator he had scarcely passed from his early pastoral seats, when he began to materialize the divine idea. What he could not see, eye to eye, he did not long believe. Symbols and images were substituted, and filled the Pagan world. All knowledge of the true God was forgotten. And God found himself in a position requiring a new revelation of himself to men. Is there any better proof that idolatry had filled the world and corrupted the race? In this declension what agent can we name so powerful in its influences as the rude symbols and images of antiquity? That the art thus became, very early, one of the chief means of propagating idolatry, we may infer from the solemn prohibition of it in the decalogue. The early employments and amusements of mankind, perhaps the very circumstances of the fine climate, soil, and spontaneous productions of the latitudes of the human family, led them to the adoption of gross material habits of thinking. Accustomed only to see and hear the great phenomena of the elemental world, they pictured out the fancied forms of the supernatural power under a thousand shapes. Infinity itself was soon the only limit to those fanciful creations. Every class of priests and magii formed a god of its own. Nor were they limited to gods of a general character.

Not satisfied with fixing the exhibition of divine power in the image of an ox, an ibis, or a cat, the oriental nations at once assigned to its operations a locality; and thus every nation and every country was furnished with a local god, and each country with its own god. How absorbing, degrading, and mentally besotting this idea became how completely it took away from the Creator the ascription of power to himself, while it placed it in material or brutal objects, and thus destroyed the responsibility of man to his Maker, the tremendous denunciations of Sinai may satisfactorily serve to explain. We allude to this passage in the Pentateuch, as the only authentic historical proof of so early a date. But it is corroborated by the universality of the practice, as proved by ancient monuments, and as traced among barbarous tribes, at the present day. If all Asia and all Africa were overrun by it, so was all America when first discovered. And in every place where the art exists, between the Arctic and Antarctic poles, we see it employed agreeably to the ancient notions; not to sustain and uphold, but to undermine and destroy the true idea of the Divinity. It is thus perceived, that the mode of communicating ideas, by the use of symbols of some sort, and with a more or less degree of perfection, was an early and a common trait of the human race. Alphabetic characters, it is thought, were known in Asia about 3317 years before the discovery of America. We must assign much of the prior era of the world to picture writing and hieroglyphics. It is proposed to inquire how far, and to what extent, the pictographic art was known to, or practised by, the American tribes.

Idle, indeed, would be the attempt, at this day, to look for the origin of the American race in any other generic quarter than the eastern continent. When they came hither? Time they came? and why they came? have been vainly inquired. But we may, it is conceived, employ the pictorial art to aid in denoting internationalism. If we take the invention of letters, as the era of their departure from the East, either with its Egyptian or Grecian date, the Ked Man came hither before this era, or, at least, before his ancestors were participants in the knowledge. Letters were used about 1822 to 2000 years before the Christian era. As he brought no such knowledge, it is inferable that he departed before that era. But he had the pictorial system he could inscribe figures and devices, in various ways, and this at least, is known, that he early developed the art in the Aztec race, and carried it to its utmost perfection.

In what respects, we may inquire, was this ancient Toltecan art superior to, or different from, the pictography of the United States tribes? Both are ideographic. Both are mnemonic to a large extent. Both appeal strongly to the power of the association of ideas by symbols. Both require interpretation by the system of ideography. Neither presents a method for the preservation of sounds. Proper names of men and animals are preserved by representative figures and drawings, and may be recalled so long as the language itself is not extinct.

With respect to the North American pictography, it may be inquired, is it universal, or confined to particular tribes?

What is the character of these devices, compared with analogous inscriptions, among the Mongolian and the wild Tartar, and the Nomadic races of Asia, and other parts of the globe? Are they mere representative symbols, or hieroglyphics? Is there more than one kind of ideographic device, or do the Indian priests and the common people use the same? Are there any characters that may be deemed hieratic? If the native jossakeeds, or medicine-men, use a more mystical method, in recording their songs, or arts, how is this denoted? Finally, is there sufficient fixity and uniformity in the application and connection of the symbols, among our forest tribes, to permit the system to be explained?

It will be evident, from these suggestions, that a new, and hitherto untrodden field of inquiry, with respect to these tribes, is hereby opened. The early history of the race is such a blank we are, in truth, so completely at a loss, for anything of a satisfactory character reaching beyond the close of the 15th century, that it behooves us, in the spirit of cautious research, to scrutinize every possible source of information. The oblivion of centuries rests upon this branch of the human family. By their physical traits they are clearly identified with some of the ancient leading stocks of Asia. But they appear to have broken off, and found their way hither, before the dawn of authentic profane history, 2 probably, as we have indicated, before the invention of letters. A few incidental notices in the early annals of Grecian literature, are all that remain, of ancient tradition, prior to Herodotus, to denote the probability of such a separation, at a remote epoch. But is this obscurity destined to be perpetual? Can it not, at least, be mitigated by a study of this ante-alphabetic branch of their antiquities? Are there no strong and undeniable coincidences, which are recorded in these pictographic symbols, between the mythology of the eastern and western hemispheres? Is there not, at least, an identity in the mode of recording idolatrous belief?

Are we prepared to conclude that the examination of their monumental ruins, in both divisions of the continent, does not furnish satisfactory evidences of identity in the general character of some elements of their astronomical knowledge, arithmetic, and geometry, as shadowed out in the Toltec and Aztec race? So in their physiology and cast of mind we perceive very striking points of similarity, from south to north, not only in their personal generic features and external traits, but also in proportion as we scrutinize the facts, in the mental habits and the intellectual structure of the Red Men of Asia and America. There is, in both, a well-developed cast of character, which is oriental, relates to the early seat of human origin, and cannot be referred to the secondary and re-produced stocks of Europe. There is nothing in the manner in which this race met and opposed the early colonists, or have, subsequently, prepared to encounter their fate, which admits a serious comparison with the purpose, forecast, and perseverance, which mark the Magyer, or any variety of the man of Europe. We must look to another quarter of the globe for our points of mental affiliation.

One of the hitherto unused evidences of this has been brought to our notice, as we apprehend, in the specimens submitted in 1825, and in 1839, of their oral imaginative propensities and lodge lore, consisting of extravagant fictions, which reveals itself in their domestic oral tales and legends. 3 We cannot be sure that, where there are so many points of similarity in the matters noticed, others may not be found, having still higher claims to attention. It is believed that there is, yet un-exhumed from their teocalli and simple cemeteries and isolated graves, objects of art and ingenuity, containing evidences which will shed important light on the era, or eras, of their primary separation from the Asiatic continent, and the islands of Oceanica. If they brought to the western hemisphere the knowledge of observing the solar cycles, and of measuring their time and adjusting their year thereby, as discoveries in Mexico and Peru denote, it is hardly probable they were behind-hand in other attainments of the same epoch. How is it that they had a cycle of 60 years, or a double cycle of 120 years, corresponding to the Chinese? How did the Mexicans adjust their year to exactly 365 days and 6 hours? We may, at least, suppose them to have been conversant with the ancient pictorial signs of the Zodiac, if not with the early Chinese mixed, or impure hieroglyphic, method of notation.

But if oral fiction be a test of mind in barbarous nations, pictography appears to be equally so. In order to fix a standard of comparison for the American ideographic symbols, it will be proper to advert to the state of these arts, as they existed in other parts of the globe, and particularly in Egypt where hieroglyphic literature was so extensively cultivated, and brought to a high degree of perfection, at an early epoch, and before the invention of letters. Letters, if we take the ordinary chronological accounts, were invented in Egypt, in 1822, B. C. This is assuming the truth of their discovery by Memnon, and places the event 331 years before the era of the Exodus. As two systems of recording ideas, of very different merit and principles, cannot be supposed to have existed long together, in a state of equal prosperity, but the better would absorb and supplant the poorer, it may be affirmed that hieroglyphics began to decline for many centuries before the Christian era. This, at least, is certain, that Moses, say in the year 1491 B. C., was well versed in the use of an alphabet of sixteen consonants, so that he recorded, as with the “pen of a ready writer,” the events which we ascribe to him. Theological critics have denied that the use of letters can be traced to an earlier date: 4 others contend for the elder theory of an uninspired invention.

Egypt was the great theater of the hieroglyphic art; but it was an art destined to be forgotten. As if the physical darkness which once shrouded it at noonday had been a type of its subsequent intellectual and moral degradation, the very knowledge of the system that once recorded thoughts in hieroglyphic language was obliterated for fifteen centuries. Letters, if they existed in Egypt at this epoch, appear to have taken their flight with the Hebrews. Knowledge was destined to be, in the end, inseparable from revelation. And when, after the rest of the world was generally enlightened, the spirit of research returned, with the French expedition to Egypt, in 1798, to the valley of the Nile, it found a land covered with monuments of forgotten greatness, and a people sunk in depths of comparative ignorance. It is supposed the mode of hieroglyphic writing was not laid aside until the third century, A. D. An earlier opinion, generally affirms that the hieroglyphic enchorial characters had ceased to be employed after the Persian conquest of Cambyses, in 525 B. C. If the Egyptians, on the invasion of the French, were found to have substituted the Arabic alphabet in place of the phonetic-hieroglyphic, and installed Mahomet s system in place of the ibis, the calf, and the cat, they had completely forgotten the event of this mutation in their literature, or that the phonetic symbols had ever been employed by them. The discovery was made by Europeans, and made alone through the perpetuating power of the Greek and Roman alphabet.

The first travelers who went to Egypt, during the latter half of the eighteenth century, did little more than wonder. They told us of pyramids, and ruined cities, and monuments covered with hieroglyphics; but the latter remained unread. Volney, Pococke, Clarke, and Bruce, imparted no other information. Kircher, who undertook it, in a work of elaborate pretense wrote a hieroglyphic romance. It has long been condemned. The first traveler of a different stamp was Belzoni. But it is not my design to recite, in detail, the discoveries of the most distinguished visitors to the banks of the Nile. It remained for the scientific corps who attended Bonaparte in his invasion of Egypt, to take the first steps, and prepare the way for the present discoveries. Amongst the monuments which were figured in “Denon’s Description of Egypt,” was the Rosetta stone. This fragment, which I examined in the British Museum in 1842, was dug up on the banks of the Nile by the French, in erecting a fort, in 1799. It is a sculptured mass of black basalt, bearing trilingual inscriptions in the hieroglyphic, the demotic, and the ancient Greek characters. Copies of it were multiplied, and spread before the scientific minds of England and the Continent, for about twenty years before the respective inscriptions were satisfactorily read. It would transcend my purpose to give the details of the history of its interpretation; but as it has furnished the key to the subsequent discoveries, and serves to denote the patience with which labors of this kind are to be met, a brief notice of the subject will be added. The Greek inscription, which is the lowermost in position, and, like the others, imperfect, was the first made out by the labors of Dr. Heyne of Germany, Professor Person of London, and by the members of the French Institute. They, at the same time, demonstrated it to be a translation.

The chief attention of the inquirers was next directed to the middle inscription, which is the most entire, and consists of the demotic, or enchorial character. The first advance was made by De Lacy, in 1802, who found, in the groups of proper names, those of Ptolemy, Arsinoe, and others. This was more satisfactorily demonstrated by Dr. Young, in 1814, when he published the result of his labors on the demotic text. These labors were further extended, and brought forward in separate papers, published by him in 1818 and 1819, in which he is believed to have shed the earliest beam of true light on the mode of annotation. He was not able, how ever, to apply his principles fully, or at least without error, from an opinion that a syllabic principle pervaded the system. He carried his interpretations, however, much beyond the deciphering of the proper names. It was the idea of this com pound character of the phonetic hieroglyphics, that proved the only bar to his full and complete success; an opinion to which he adhered in 1823, in a paper in which he maintains, that the Egyptians did not make use of an alphabet to represent elementary sounds and their connection, prior to the era of the Grecian and Roman domination. Champollion the Younger himself entertained very much the same opinion, so far, at least, as relates to the phonetic signs, in 1812. In 1814, in hi? “Egypt under the Pharaohs,” he first expresses a different opinion, and throws out the hope, that “sounds of language and the expressions of thought,” would yet be disclosed under the garb of “material pictures.” This was, indeed, the germ in the thought-work of the real discovery, which he announced to the Royal Academy of Belles Letters at Paris, in September, 1822. By this discovery, of which Dr. Young claims priority, in determining the first nine symbols, a new link is added in the communication of thought by signs, which connects picture and alphabet writing. Phonetic hieroglyphics, as thus disclosed, consist of symbols representing the sounds of first letters of words. These symbols have this peculiarity, and are restricted to this precise use: that while they depict the ideas of whole objects, as birds, &c., they represent only the alphabetic value of the initial letter of the name of these objects. Thus the picture may, to give an example in English, denote a man, an ox, an eagle, or a lotus; but their alphabetical value, if these be the words inscribed on a column, would be respectively, the letters M. 0. E. L. These are the phonetic signs, or equivalents for the words. It is evident that an inscription could thus be made, with considerable precision, but not unerring exactitude, and it is by the discovery of this key, that so much light has been, within late years, evolved from the Egyptian monuments.

It may be useful, in this connection, to bear in mind two facts, namely, that the discovery aims at greater accuracy and precision, than it has attained; and that, the result, striking and brilliant as it confessedly is, is the accumulation of the patient research of many years, and a plurality of intellects. Without the accidental discovery of the Rosetta stone, containing the trilingual inscription, it is doubtful whether the system would have ever been guessed at. And here is one, and we think by far the greatest benefit, which the world owes to the French invasion of Egypt. It has been seen, that the first step to an interpretation, was the detection of the proper names, as disclosed by the Greek copy, coupled with the linguistical conclusion arrived at by Heyne. Scholars perceived that this Greek text must be a ” translation” This hint gave the impulse to research. What was translated must necessarily have had an original.

The next step was taken by Quatremere, who proved the present Coptic to be identical with the ancient Egyptian. To find this language, then, recorded in the hieroglyphics, was the great object. It is here that the younger Champollion exercised his power of definition and comparison. By the pre-conception of a phonetic hieroglyphical alphabet, as above denoted, he had grasped the truth, which yet lay concealed, and he labored at it until he verified his conceptions. It is thus that a theory gives energy to research; nor is there much hope of success without one, in the investigation of the unknown. Columbus had never reached America, without a theory. Nor did this investigation want the additional stimulus of rivalry. The discoveries of Dr. Young, and the injudicious criticisms and wholesale praises of the British press, (particularly the London Quarterly,) of his papers on the hieroglyphic literature of Egypt, were calculated to arouse in France and Germany a double feeling of rivalry. It was not only a question between the respective archaeological merits of Dr. Young and M. Champollion; it was also a question of national pride between England, France, and Germany. And, for the first time in their fierce and sanguinary history, hieroglyphics were the missives wielded. Victory decided in favor of Champollion, as displayed in the triumph of the pure phonetic method elucidated in his “Précis du systéme hiéroglyphiques des anciens Egyptians,” published in 1824.

It is a striking feature in hieroglyphical phonetic writing, and the great cause of imprecision, that its signs are multiform, often arbitrary, and must be constantly interpreted, not only with an entire familiarity with the language of the people employing them, but with their customs, habits, arts, manners, and history. All who have studied the Egyptian hieroglyphic literature, have experienced this. The number of phonetic synonyms, or homoplianous signs, in the phonetic alphabet, has been increased, at the last dates, to 864. Of this number, 120 are devoted to the human figure, in various positions, and 60 to separate parts of the body. 10 represent celestial bodies; 24, wild, and 10, domestic quadrupeds; 22, limbs of animals; 50, birds and parts of birds; 10, fishes; 30, reptiles, and portions of reptiles; 14, insects; 60, vegetables, plants, flowers, and fruits; 50, fantastic, arbitrary forms; and the remaining 404, artificial objects. Nor is it supposed that this is the full extent of the phonetic signs.

Homophons have been added to the list by every new discoverer, and .the best results which are now predicted for the alphabet, denote that the round number of 900 is expected to comprise all the various signs. Where an alphabet is so diffuse, there must be danger of error and imprecision. We do not fall in with the too-sweeping conclusions of some erudite critics, against the general value of the principles and results; which, however, must be received with abatements. It is sufficient to bear in mind, as a reason for caution, that the interpretations of different minds vary; and that Rossolini and Champollion did not coincide. There is a manifest tendency, at the present day, to over-estimate the civilization, learning, and philosophy of the Egyptians and Persians in these departments, chiefly from hieroglyphic and pictorial records. If I mistake not, we are in some danger of falling into this error, on this side of the water, in relation to the character of the ancient Mexican civilization. The impulsive glow of one of our most chaste and eloquent historians, gives this natural tendency to our conceptions. The Aztec semi-civilization was an industrial civilization; the giving up of hunting and roving for agriculture and fixed dwellings. But we must not mistake it. They built teocalli, temples, palaces, and gardens; but the people lived in mere huts. They were still debased. Woman was dreadfully so. The mind of the Aztecs, while the hand had obtained skill and industry, was still barbaric. The horrific character of their religion made it impossible it should be otherwise. Civilization had but little affected the intellect, the morals not at all. They commemorated events by the striking system of picture-writing; but there is strong reason to suspect, since examining the principles of the North American system, as practiced by our medas and jossakeeds, that the Mexican manuscripts were also constructed on the mnemonic principle, and always owed much of their value and precision to the memory of the trained writers and painters. If these occupied, before the law-chiefs of Montezuma, the relative position of clerks of courts and recorders, as some of the picture-writings preserved by Hackluyt denote, these interpreters of the national rolls relied greatly on memory. Conventional signs had done much, but the painted record still required these verbal explanations which a knowledge of the system only could supply.

Citations:

- Genesis.[

]

- The era of Herodotus is 413 B. C.[

]

- Vide Algic Researches.[

]

- See Dr. Spring’s Obligations to the Bible.[

]