Apart from the more material and substantive relations between signs and language, it is to be expected that analogies can by proper research be ascertained between their several developments in the manner of their use, that is, in their grammatic mechanism, and in the genesis of the sentence. The science of language, ever henceforward to be studied historically, must take account of the similar early mental processes in which the phrase or sentence originated, both in sign and oral utterance. In this respect, as in many others, the North American Indians may be considered to be living representatives of prehistoric man.

Syntax

The reader will understand without explanation that there is in the gesture speech no organized sentence such as is integrated in the languages of civilization, and that he must not look for articles or particles or passive voice or case or grammatic gender, or even what appears in those languages as a substantive or a verb, as a subject or a predicate, or as qualifiers or inflexions. The sign radicals, without being specifically any of our parts of speech, may be all of them in turn. There is, however, a grouping and sequence of the ideographic pictures, an arrangement of signs in connected succession, which may be classed under the scholastic head of syntax. This subject, with special reference to the order of deaf-mute signs as compared with oral speech, has been the theme of much discussion, some notes of which, condensed from the speculations of M. Rémi Valade and others, follow in the next paragraph without further comment than may invite attention to the profound remark of Leibnitz.

In mimic construction there are to be considered both the order in which the signs succeed one another and the relative positions in which they are made, the latter remaining longer in the memory than the former, and spoken language may sometimes in its early infancy have reproduced the ideas of a sign picture without commencing from the same point. So the order, as in Greek and Latin, is very variable. In nations among whom the alphabet was introduced without the intermediary to any impressive degree of picture-writing, the order being (1) language of signs, almost superseded by (2) spoken language, and (3) alphabetic writing, men would write in the order in which they had been accustomed to speak. But if at a time when spoken language was still rudimentary, intercourse being mainly carried on by signs, figurative writing had been invented, the order of the figures would be the order of the signs, and the same order would pass into the spoken language. Hence Leibnitz says truly that “the writing of the Chinese might seem to have been invented by a deaf person.” The oral language has not known the phases which have given to the Indo-European tongues their formation and grammatical parts. In the latter, signs were conquered by speech, while in the former, speech received the yoke.

Sign language cannot show by inflection the reciprocal dependence of words and sentences. Degrees of motion corresponding with vocal intonation are only used rhetorically or for degrees of comparison. The relations of ideas and objects are therefore expressed by placement, and their connection is established when necessary by the abstraction of ideas. The sign talker is an artist, grouping persons and things so as to show the relations between them, and the effect is that which is seen in a picture. But though the artist has the advantage in presenting in a permanent connected scene the result of several transient signs, he can only present it as it appears at a single moment. The sign talker has the succession of time at his disposal, and his scenes move and act, are localized and animated, and their arrangement is therefore more varied and significant.

It is not satisfactory to give the order of equivalent words as representative of the order of signs, because the pictorial arrangement is wholly lost; but adopting this expedient as a mere illustration of the sequence in the presentation of signs by deaf-mutes, the following is quoted from an essay by Rev. J.R. Keep, in American Annals of the Deaf and Dumb, vol. xvi, p. 223, as the order in which the parable of the Prodigal Son is translated into signs:

“Once, man one, sons two. Son younger say, Father property your divide: part my, me give. Father so.Son each, part his give. Days few after, son younger money all take, country far go, money spend, wine drink, food nice eat. Money by and by gone all. Country everywhere food little: son hungry very. Go seek man any, me hire. Gentleman meet. Gentleman son send field swine feed. Son swine husks eat, seeself husks eat wantcannothusks him give nobody. Son thinks, say, father my, servants many, bread enough, part give away canI nonestarve, die. I decide: Father I go to, say I bad, God disobey, you disobeyname my hereafter son, noI unworthy. You me work give servant like. So son begin go. Father far look: son see, pity, run, meet, embrace. Son father say, I bad, you disobey, God disobeyname my hereafter son, noI unworthy. But father servants call, command robe best bring, son put on, ring finger put on, shoes feet put on, calf fat bring, kill. We all eat, merry. Why? Son this my formerly dead, now alive: formerly lost, now found: rejoice.”

It may be remarked, not only from this example, but from general study, that the verb “to be” as a copula or predicant does not have any place in sign language. It is shown, however, among deaf-mutes as an assertion of presence or existence by a sign of stretching the arms and hands forward and then adding the sign of affirmation. Time as referred to in the conjunctions when and then is not gestured. Instead of the form, “When I have had a sleep I will go to the river,” or “After sleeping I will go to the river,” both deaf-mutes and Indians would express the intention by “Sleep done, I river go.” Though time present, past, and future is readily expressed in signs (see page 366), it is done once for all in the connection to which it belongs, and once established is not repeated by any subsequent intimation, as is commonly the case in oral speech. Inversion, by which the object is placed before the action, is a striking feature of the language of deaf-mutes, and it appears to follow the natural method by which objects and actions enter into the mental conception. In striking a rock the natural conception is not first of the abstract idea of striking or of sending a stroke into vacancy, seeing nothing and having no intention of striking anything in particular, when suddenly a rock rises up to the mental vision and receives the blow; the order is that the man sees the rock, has the intention to strike it, and does so; therefore he gestures, “I rock strike.” For further illustration of this subject, a deaf-mute boy, giving in signs the compound action of a man shooting a bird from a tree, first represented the tree, then the bird as alighting upon it, then a hunter coming toward and looking at it, taking aim with a gun, then the report of the latter and the falling and the dying gasps of the bird. These are undoubtedly the successive steps that an artist would have taken in drawing the picture, or rather successive pictures, to illustrate the story. It is, however, urged that this pictorial order natural to deaf-mutes is not natural to the congenitally blind who are not deaf-mute, among whom it is found to be rhythmical. It is asserted that blind persons not carefully educated usually converse in a metrical cadence, the action usually coming first in the structure of the sentence. The deduction is that all the senses when intact enter into the mode of intellectual conception in proportion to their relative sensitiveness and intensity, and hence no one mode of ideation can be insisted on as normal to the exclusion of others.

Whether or not the above statement concerning the blind is true, the conceptions and presentations of deaf-mutes and of Indians using sign language because they cannot communicate by speech, are confined to optic and, therefore, to pictorial arrangement.

The abbé Sicard, dissatisfied with the want of tenses and conjunctions, indeed of most of the modern parts of speech, in the natural signs, and with their inverted order, attempted to construct a new language of signs, in which the words should be given in the order of the French or other spoken language adopted, which of course required him to supply a sign for every word of spoken language. Signs, whatever their character, could not become associated with words, or suggest them, until words had been learned. The first step, therefore, was to explain by means of natural signs, as distinct from the new signs styled methodical, the meaning of a passage of verbal language. Then each word was taken separately and a sign affixed to it, which was to be learned by the pupil. If the word represented a physical object, the sign would be the same as the natural sign, and would be already understood, provided the object had been seen and was familiar; and in all cases the endeavor was to have the sign convey as strong a suggestion of the meaning of the word as was possible. The final step was to gesticulate these signs, thus associated with words, in the exact order in which the words were to stand in a sentence. Then the pupil would write the very words desired in the exact order desired. If the previous explanation in natural signs had not been sufficiently full and careful, he would not understand the passage. The methodical signs did not profess to give him the ideas, except in a very limited degree, but only to show him how to express ideas according to the order and methods of spoken language. As there were no repetitions of time in narratives in the sign language, it became necessary to unite with the word-sign for verbs others, to indicate the different tenses of the verbs, and so by degrees the methodical signs not only were required to comprise signs for every word, but also, with every such sign, a grammatical sign to indicate what part of speech the word was, and, in the case of verbs, still other signs to show their tenses and corresponding inflections. It was, as Dr. Peet remarks, a cumbrous and unwieldy vehicle, ready at every step to break down under the weight of its own machinery. Nevertheless, it was industriously taught in all our schools from the date of the founding of the American Asylum in 1817 down to about the year 1835, when it was abandoned.

The collection of narratives, speeches, and dialogues of our Indians in sign language, first systematically commenced by the present writer, several examples of which are in this paper, has not yet been sufficiently complete and exact to establish conclusions on the subject of the syntactic arrangement of their signs. So far as studied it seems to be similar to that of deaf-mutes and to retain the characteristic of pantomimes in figuring first the principal idea and adding the accessories successively in the order of importance, the ideographic expressions being in the ideologic order. If the examples given are not enough to establish general rules of construction, they at least show the natural order of ideas in the minds of the gesturers and the several modes of inversion by which they pass from the known to the unknown, beginning with the dominant idea or that supposed to be best known. Some special instances of expedients other than strictly syntactic coming under the machinery broadly designated as grammar may be mentioned.

Degrees of Comparison

Degrees of comparison are frequently expressed, both by deaf-mutes and by Indians, by adding to the generic or descriptive sign that for “big” or “little.” Damp would be “wetlittle”; cool, “coldlittle”; hot, “warmmuch.” The amount or force of motion also often indicates corresponding diminution or augmentation, but sometimes expresses a different shade of meaning, as is reported by Dr. Matthews with reference to the sign for bad and contempt, see page 411. This change in degree of motion is, however, often used for emphasis only, as is the raising of the voice in speech or italicizing and capitalizing in print. The Prince of Wied gives an instance of a comparison in his sign for excessively hard, first giving that for hard, viz: Open the left hand, and strike against it several times with the right (with the backs of the fingers). Afterwards he gives hard, excessively, as follows: Sign for hard, then place the left index-finger upon the right shoulder, at the same time extend and raise the right arm high, extending the index-finger upward, perpendicularly.

Rev. G.L. Deffenbaugh describes what may perhaps be regarded as an intensive sign among the Sahaptins in connection with the sign for good; i.e., very good. “Place the left hand in position in front of the body with all fingers closed except first, thumb lying on second, then with forefinger of right hand extended in same way point to end of forefinger of left hand, move it up the arm till near the body and then to a point in front of breast to make the sign good.” For the latter see Extracts from Dictionary page 487, infra. The same special motion is prefixed to the sign for bad as an intensive.

Another intensive is reported by Mr. Benjamin Clark, interpreter at the Kaiowa, Comanche, and Wichita agency, Indian Territory, in which after the sign for bad is made, that for strong is used by the Comanches as follows: Place the clinched left fist horizontally in front of the breast, back forward, then pass the palmar side of the right fist downward in front of the knuckles of the left.

Dr. W.H. Corbusier, assistant surgeon U.S.A., writes as follows in response to a special inquiry on the subject: “By carrying the right fist from behind forward over the left, instead of beginning the motion six inches above it, the Arapaho sign for strong is made. For brave, first strike the chest over the heart with the right fist two or three times, and then make the sign for strong.

“The sign for strong expresses the superlative when used with other signs; with coward it denotes a base coward; with hunger, starvation; and with sorrow, bitter sorrow. I have not seen it used with the sign for pleasure or that of hunger, nor can I learn that it is ever used with them.”

Opposition

The principle of opposition, as between the right and left hands, and between the thumb and forefinger and the little finger, appears among Indians in some expressions for “above,” “below,” “forward,” “back,” but is not so common as among the methodical, distinguished from the natural, signs of deaf-mutes. It is also connected with the attempt to express degrees of comparison. Above is sometimes expressed by holding the left hand horizontal, and in front of the body, fingers open, but joined together, palm upward. The right hand is then placed horizontal, fingers open but joined, palm downward, an inch or more above the left, and raised and lowered a few inches several times, the left hand being perfectly still. If the thing indicated as “above” is only a little above, this concludes the sign, but if it be considerably above, the right hand is raised higher and higher as the height to be expressed is greater, until, if enormously above, the Indian will raise his right hand as high as possible, and, fixing his eyes on the zenith, emit a duplicate grunt, the more prolonged as he desires to express the greater height. All this time the left hand is held perfectly motionless. Below is gestured in a corresponding manner, all movement being made by the left or lower hand, the right being held motionless, palm downward, and the eyes looking down.

The code of the Cistercian monks was based in large part on a system of opposition which seems to have been wrought out by an elaborate process of invention rather than by spontaneous figuration, and is more of mnemonic than suggestive value. They made two fingers at the right side of the nose stand for “friend,” and the same at the left side for “enemy,” by some fanciful connection with right and wrong, and placed the little finger on the tip of the nose for “fool” merely because it had been decided to put the forefinger there for “wise man.”

Proper Names

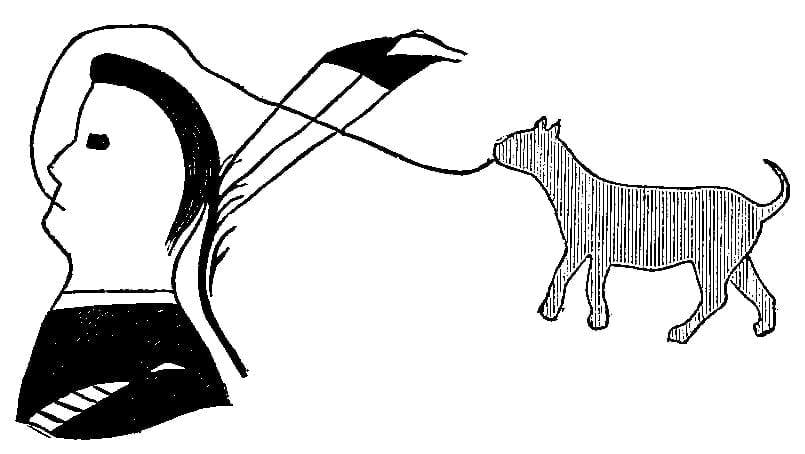

It is well known that the names of Indians are almost always connotive, and particularly that they generally refer to some animal, predicating often some attribute or position of that animal. Such names readily admit of being expressed in sign language, but there may be sometimes a confusion between the sign expressing the animal which is taken as a name-totem, and the sign used, not to designate that animal, but as a proper name. A curious device to differentiate proper names was observed as resorted to by a Brulé Dakota. After making the sign of the animal he passed his index forward from the mouth in a direct line, and explained it orally as “that is his name,” i.e., the name of the person referred to. This approach to a grammatic division of substantives maybe correlated with the mode in which many tribes, especially the Dakotas, designate names in their pictographs, i.e., by a line from the mouth of the figure drawn representing a man to the animal, also drawn with proper color or position. Fig. 150 thus shows the name of Shun-ka Luta, Red Dog, an Ogallalla chief, drawn by himself. The shading of the dog by vertical lines is designed to represent red, or gules, according to the heraldic scheme of colors, which is used in other parts of this paper where it seemed useful to designate particular colors. The writer possesses in painted robes many examples in which lines are drawn from the mouth to a name-totem.

It would be interesting to dwell more than is now allowed upon the peculiar objectiveness of Indian proper names with the result, if not the intention, that they can all be signified in gesture, whereas the best sign-talker among deaf-mutes is unable to translate the proper names occurring in his speech or narrative and, necessarily ceasing signs, resorts to the dactylic alphabet. Indians are generally named at first according to a clan or totemic system, but later in life often acquire a new name or perhaps several names in succession from some exploit or adventure. Frequently a sobriquet is given by no means complimentary. All of the subsequently acquired, as well as the original names, are connected with material objects or with substantive actions so as to be expressible in a graphic picture, and, therefore, in a pictorial sign. The determination to use names of this connotive character is shown by the objective translation, whenever possible, of those European names which it became necessary to introduce into their speech. William Penn was called “Onas,” that being the word for feather-quill in the Mohawk dialect. The name of the second French governor of Canada was “Montmagny” which was translated by the Iroquois “Onontio””Great Mountain,” and becoming associated with the title, has been applied to all successive Canadian governors, though the origin being generally forgotten, it has been considered as a metaphorical compliment. It is also said that Governor Fletcher was not named by the Iroquois “Cajenquiragoe,” “the great swift arrow,” because of his speedy arrival at a critical time, but because they had somehow been informed of the etymology of his name”arrow maker” (Fr. fléchier).

Gender

This is sometimes expressed by different signs to distinguish the sex of animals, when the difference in appearance allows of such varied portraiture. An example is in the signs for the male and female buffalo, given by the Prince of Wied. The former is, “Place the tightly closed hands on both sides of the head, with the fingers forward;” the latter is, “Curve the two forefingers, place them on the sides of the head and move them several times.” The short stubby horns of the bull appear to be indicated, and the cow’s ears are seen moving, not being covered by the bull’s shock mane. Tribes in which the hair of the women is differently arranged from that of men often denote their females by corresponding gesture. In many cases the sex of animals is indicated by the addition of a generic sign for male or female.

Tense

While it has been mentioned that there is no inflection of signs to express tense, yet the conception of present, past, and future is gestured without difficulty. A common mode of indicating the present time is by the use of signs for to-day, one of which is, “(1) both hands extended, palms outward; (2) swept slowly forward and to each side, to convey the idea of openness.” (Cheyenne II.) This may combine the idea of now with openness, the first part of it resembling the general deaf-mute sign for here or now.

Two signs nearly related together are also reported as expressing the meaning now, at once, viz.: “Forefinger of the right hand extended, upright, &c. (J), is carried upward in front of the right side of the body and above the head so that the extended finger points toward the center of the heavens, and then carried downward in front of the right breast, forefinger still pointing upright.” (Dakota I.) “Place the extended index, pointing upward, palm to the left, as high as and before the top of the head; push the hand up and down a slight distance several times, the eyes being directed upward at the time.” (Hidatsa I; Kaiowa I; Arikara I; Comanche III; Apache II; Wichita II.)

Time past is not only expressed, but some tribes give a distinct modification to show a short or long time past. The following are examples:

Lately, recently. Hold the left hand at arm’s length, closed, with forefinger only extended and pointing in the direction of the place where the event occurred; then hold the right hand against the right shoulder, closed, but with index extended and pointing in the direction of the left. The hands may be exchanged, the right extended and the left retained, as the case may require for ease in description. (Absaroka I; Shoshoni and Banak I.)

Long ago. Both hands closed, forefingers extended and straight; pass one hand slowly at arm’s length, pointing horizontally, the other against the shoulder or near it, pointing in the same direction as the opposite one. Frequently the tips of the forefingers are placed together, and the hands drawn apart, until they reach the positions described. (Absaroka I; Shoshoni and Banak I.)

The Comanche, Wichita, and other Indians designate a short time ago by placing the tips of the forefinger and thumb of the left hand together, the remaining fingers closed, and holding the hand before the body with forefinger and thumb pointing toward the right shoulder; the index and thumb of the right hand are then similarly held and placed against those of the left, when the hands are slowly drawn apart a short distance. For a long time ago the hands are similarly held, but drawn farther apart. Either of these signs may be and frequently is preceded by those for day, month, or year, when it is desired to convey a definite idea of the time past.

A sign is reported with the abstract idea of future, as follows: “The arms are flexed and hands brought together in front of the body as in type-position (W). The hands are made to move in wave-like motions up and down together and from side to side.” (Oto I.) The authority gives the poetical conception of “Floating on the tide of time.”

The ordinary mode of expressing future time is, however, by some figurative reference, as the following: Count off fingers, then shut all the fingers of both hands several times, and touch the hair and tent or other white object. (Apache III.) “Many years; when I am old (whitehaired).”

Conjunctions

An interesting instance where the rapid connection of signs has the effect of the conjunction and is shown in Nátci’s Narrative, infra.

Prepositions

In the Tendoy-Huerito Dialogue (page 489) the combination of gestures supplies the want of the proposition to.

Punctuation

While this is generally accompanied by facial expression, manner of action, or pause, instances have been noticed suggesting the device of interrogation points and periods.

Mark of interrogation

The Shoshoni, Absaroka, Dakota, Comanche, and other Indians, when desiring to ask a question, precede the gestures constituting the information desired by a sign intended to attract attention and “asking for,” viz., by holding the flat right hand, with the palm down, directed, to the individual interrogated, with or without lateral oscillating motion; the gestural sentence, when completed, being closed by the same sign and a look of inquiry. This recalls the Spanish use of the interrogation points before and after the question.

Period

A Hidatsa, after concluding a short statement, indicated its conclusion by placing the inner edges of the clinched hands together before the breast, and passing them outward and downward to their respective sides in an emphatic manner, Fig. 334, page 528. This sign is also used in other connections to express done.

The same mode of indicating the close of a narrative or statement is made by the Wichitas, by holding the extended left hand horizontally before the body, fingers pointing to the right, palm either toward the body or downward, and cutting edgewise downward past the tips of the left with the extended right hand. This is the same sign given in the Address of Kin Chēĕss as cut off, and is illustrated in Fig. 324, page 522. This is more ideographic and convenient than the device of the Abyssinian Galla, reported by M.A. d’Abbadie, who denoted a comma by a slight stroke of a leather whip, a semicolon by a harder one, and a full stop by one still harder.