Seventeenth century British maps show the word “Rickohockens” spread across the mountains of southwest Virginia and northwestern North Carolina. 1 There has been virtually no study of the Rickohockens by Southeastern anthropologists since John Swanton arbitrarily listed the word as one of the alternative names of the Yuchi Indians. 2 On the same page, he listed the Tamahitans as also being an alternative name for the Yuchi, even though the Tamahiti (actual name) were a Creek people with an Itza Maya name. Swanton obviously had no linguistic evidence to create that list. Now Cherokee historians arbitrarily list the Tamahitans as being an earlier name for the Cherokees.

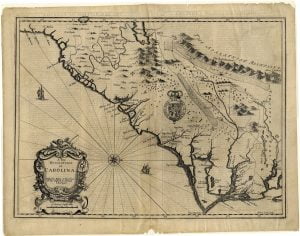

The word, “Rickohocken,” appeared suddenly in the discussions of the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1644, and was frequently mentioned thereafter until 1684. 3 No word similar to Rickohocken appeared on Virginia maps before 1644, while such southwestern Virginia tribes as the Tomahitan, Saponi and Occaneechi did. The Rickohockens were shown on British maps to control southwestern Virginia, southeastern Kentucky, northeastern Tennessee and northwestern North Carolina until the early 1700s.

In 1718 a map by French cartographer, Guilluame DeLisle, introduced for the first time, the word, “Charaqui.” 4 The Charaqui Indians were shown to control the exact same territory as the Rickohockens.

The Rickohocken capital, Otari, was said to be located high in the Virginia Mountains beneath the Peaks of the Otter. Spanish explorer, Juan Pardo, established a small mission in a town named Otari in 1567, but it may have not been the same town. 5 The word, Otter, is supposedly derived from Otari. Many “cut and paste” Cherokee histories state that Otari means “high place” in Cherokee, and use that as justification that the Rickohockens were really Cherokees. However, the “real” Cherokee word for “high place” is gal v la di – yi. 6 There is no similarity at all.

Very few of the Rickohocken words survive. Their village sites have never been studied by archaeologists. Every now and then, a scholar tries to translate their name with one of the known indigenous languages of Virginia and can’t. Little else is known today about the Rickohockens. Any further research is hampered by the consistent tendency of North Carolina and southwestern Virginia historians to arbitrarily substitute the word “Cherokee” for any indigenous ethnic nam

e that didn’t make to the list of federally recognized tribes.

An alternative name for the Rickohockens survived until the mid-1700s in the Lower South. A large band of Rickohockens, who raided the Lower Southeast for years but eventually settled near Augusta, GA in the late 1660’s or early 1670’s, called their principal town, Rickohocken, but became known as the Weste to nearby Creek Indians. 7 Weste became Westo among South Carolina planters. In some Colonial documents, alternative versions of the Rickohocken’s name appear. They include Rechahecrian, Rikeehoken, Rikeherren, Richerren, Recherren or Rickoherron.

In July 2013, Principal Chief Don Greene of the Appalachian Shawnee Tribe sent the author the following message via email: “I have always been told by older Chiefs that the Rickohocken were from the Raccoon Clan that was part of or related closely to the Erie or Panther clan from the lower tip of Lake Erie, hence the Petit Chat/Little Cat clan or tribe that the French fur traders dealt with. When the soon-to-be Iroquois were armed and sent out on slave raids (now called the Beaver Wars), some of the Panther/Erie and Raccoon clans fled south but were wiser for the experience. When they crossed the Appalachian Mountains they sought out the first whites they could find, the Virginians, and tried to work out a similar slave-trading agreement with them.”

On July 20, 1661, a Westo war party canoed down the Altamaha River and destroyed the Spanish mission of Santo Domingo de Talaje near present-day Darien. 8 From 1675 to 1680, trade between the Westo and South Carolina thrived. 9 The Westo provided Carolina with slaves, captured from various Native American groups. They preferred to attack mission Indians along the coast of what is now Georgia, because they were generally unarmed, and had been “pacified” by the Spanish friars.

Shortly after the English captured New Amsterdam in 1664, the Westo Band began making frequent ethnic cleansing raids from southwest Virginia to South Carolina and Georgia to obtain slaves. However, there were so many slaves to be captured in the South, that they found more it efficient stay permanently at a strategic location in the south and march the slaves northward to Virginia markets. 10 After 1671 they could march them straight to the Carolina coast. It was like someone in Virginia told them that a new market for their slaves was going to be founded in a couple of years on the South Carolina coast.

After being defeated badly by the Savano Indians in 1680, surviving Westo migrated to the Lower Chattahoochee River and joined the Creek Confederacy. Their name appears on maps adjacent to the Chattahoochee River until after the American Revolution. This was about the last time that Virginia archives mentioned the Rickohockens.

Georgia and South Carolina scholars have not determined the meaning of Westo either. The Creek Indian word, weste, now means a savage or a Native American with long, scraggly hair. 11 However that is pejorative word that was derived from the Creek name for the Westo Indians.

There is a dictionary that can translate the phonetics of Rickohocken and Weste. 12 It is a Nederlandische (Dutch) dictionary. Rijke means kingdom, nation or rich. Hoogen means high or lofty. Therefore, Rijkehoogen, means “high kingdom.” The Dutch word woeste means wild, fierce, violent and is pronounced almost exactly like the Creek word, weste. The origin of Richerren is the easiest one to solve. Phonetically, Rik-herren is the same in all the Northern Germanic/Scandinavian languages. It means, “Rich Gentlemen.”

Why would a Native American tribe, who were one of the main players in the Native American slave raids, have names from a nation that was a principal player in the Atlantic slave trade during that era? There could be some interesting answers.

Citations:

- Lumb, Francis, “A New Description of Carolina” (Map) – 1676. The Rickohocken’s name is prominently displayed on the map as being the only occupant of the Virginia and NW North Carolina Mountains.[

]

- Swanton, John Reed. Early History of the Creek Indians and Their Neighbors. US Government Printing Office. 1902.[

]

- Thornton, Richard, “Berkeley the Butcher,” Bacons Rebellion Magazine, September 4, 2007.[

]

- DeLisle, Guilluame, “Carte de la Louisiane et du Cours du Mississipi” (map) 1718.[

]

- De la Bandera, Juan, Relaccion de la Florida, 1568. The chronicles of the Juan Pardo expedition.[

]

- Cherokee Online Dictionary sponsored by Georgia Southern University.[

]

- Bowne, Eric E., Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, “Westo Indians,” New Georgia Encyclopedia.[

]

- Worth, John E., University of West Florida, Pensacola, “Mission Santo Domingo de Talaje,” New Georgia Encyclopedia.[

]

- Bowne, Eric E., Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, “Westo Indians,” New Georgia Encyclopedia.[

]

- Bowne, Eric E., Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, “Westo Indians,” New Georgia Encyclopedia.[

]

- Martin, John B. & Mauldin, Margaret M., Dictionary of Muskogee/Creek, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.[

]

- Nederlands Online Dictionary.[

]