The Use of Rawhide. In the use of rawhide for binding and hafting (handle or strap), the Plains tribes seem almost unique. When making mauls and stone-headed clubs a piece of green or wet hide is firmly sewed on and as this dries its natural shrinkage sets the parts firmly. This is nicely illustrated in saddles. Thus, rawhide here takes the place of nails, twine, cement, etc., in other cultures.

The Partleche

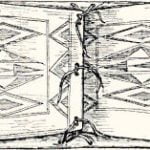

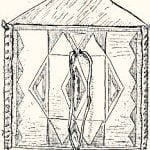

A number of characteristic bags were made of rawhide, the most conspicuous being the parfleche. Its simplicity of construction is inspiring and its usefulness scarcely to be over-estimated. The approximate form for a parfleche is shown in Fig. 23, and its completed form in Fig. 24. The side outlines as in Fig. 23 are irregular and show great variations, none of which can be taken as certainly characteristic. To fill the parfleche, it is opened out as in Fig. 23, and the contents arranged in the middle.

The large flap is then brought over and held by lacing a , a”. The ends are then turned over and laced, b , b”. The closed parfleche may then be secured by both or either of the looped thongs at c , c”.

Primarily, parfleche were used for holding dried meat, dried berries, tallow, etc., though utensils and other be longings found their way into them when convenient. In recent years, they seem to have more of a decorative than a practical value; or rather, according to our impression, they are cherished as mementos of buffalo days, the great good old time of Indian memory, always appropriate and acceptable as gifts. The usual fate of a gift parfleche is to be cut into moccasin soles. With the possible exception of the Osage, the parfleche was common among all these tribes but seldom en countered elsewhere.

Rawhide Bags

A rectangular bag (Fig. 25) was also common and quite uniform even to the modes of binding. They were used by women rather than by men. The larger ones may contain skin-dressing tools, the smaller ones, sewing or other small implements, etc. Sometimes, they were used in gathering berries and other vegetable foods. A cylindrical rawhide case used for headdresses and other ceremonial objects is characteristic (Fig. 26). All these objects made of rawhide are further characterized by their highly individualized painted decorations (p. 127).

Soft Bags

The Dakota made some picturesque soft bags used in pairs, and called “A bag for every possible thing.” The collection contains many fine examples some of which are of buffalo hide. All are skillfully decorated with quills or beads (Fig. 27).

This type occurs among the Assiniboin, Gros Ventre, Dakota, Crow, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Ute, and Wind River Shoshoni in almost identical forms, but among the Nez Perce and Bannock with decided differences.

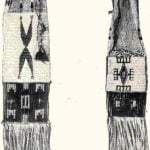

Perhaps equally typical of the area were the long slender bags for smoking outfits. These are especially conspicuous in Dakota collections where they range from 80 to 150 cm. in length. At the ends, they have rows of rawhide strips wrapped with quills and below a fringe of buckskin (Fig. 28).

The Dakota type has been noted among the Assiniboin, Cheyenne, Crow, and Hidatsa, but rarely among the Ute, Arapaho, or Shoshoni. The Kiowa and Comanche make one, but with an entirely different fringe. The Blackfoot, Northern Shoshoni, Plains-Cree, and Sarsi use a smaller pouch of quite a different type, also reported from the Saulteaux and Cree of the Woodland area.

These objects are, however, so often presented to visiting Indians that collectors find it difficult to separate the intrusions from the native samples for any particular tribe.

We have some reason for thinking that the Dakota type is quite recent, for the Teton claim that formerly the entire skins of young antelope, deer, and even birds and beavers were used as smoking bags. Some examples of such bags have been collected and are quite frequent in the ceremonial outfits of the Blackfoot. Again, the collections from many tribes contain bags made from the whole skins of unborn buffalo and deer, used for gathering berries and storing dried food, from which it is clear that a general type of seamless bag was once widely used. All this raises the question as to whether the introduction of metal cutting and sewing implements during the historic period may not have influenced the development of these long, rectangular fringed pipe bags.

The strike-a-light pouch

Made of modern commercial leather is common to the Wind River Shoshoni, Ute, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Dakota, Gros Ventre, and Assiniboin (Fig. 29). Among the Arapaho and Gros Ventre we also find a large pouch of similar designs. Again, the Northern Shoshoni and Blackfoot are not included, neither are these pouches frequent among the Kiowa and Comanche.

Many of the paint bags used by the Blackfoot resemble their pipe bags even to the fringe and the flaps at the mouth. However, many paint bags in ceremonial outfits are without fringes or decorations of any kind. Some have square cut bases and some curved; their lengths range from 8 to 15 cm. In some cases, those with square cut bases are provided with a pendant at each corner. Decorated paint bags of the fringed type occur among the Gros Ventre, Assiniboin, Arapaho, Sarsi, Dakota, and Shoshoni. A specimen without the fringe appears in the Comanche collection. The Blackfoot, Sarsi, Gros Ventre, and Assiniboin use almost exclusively, bags with the flaps at the top, and bearing similar decorations. The Arapaho and Dakota incline to this type but also use those with straight tops. Among the Shoshoni decorated paint bags are rare, but two specimens we have observed belong to these respective types. So far, it seems that the Arapaho alone, use the peculiar paint bag with a triangular tail, suggesting the ornamented pendants to the animal skin medicine bags of the Algonquin in the Woodland area. However, we have seen a large bag of this pattern attributed to the Bannock.

A round-bottomed pouch with a decorated field and a transverse fringe was sometimes used for paint by the Blackfoot. The decorated part is on stiff rawhide while the upper is of soft leather, the sides and mouth of which are edged by two and three rows of beads respectively. This seems to be an unusual form for the Blackfoot and rare in other collections; while the related form, a large rounded bag, frequently encountered in Dakota and Assiniboin collections has not been observed among the northern group of tribes. The Blackfoot collection contains two small, flat rectangular cases with fringes. One of these was said to have been made for a mirror, the other for matches. However, such cases were formerly used by many tribes for carrying the ration ticket issued by the government. Their distribution seems to have been general in the Plains.

Some tribes used a long double saddle bag, highly decorated and fringed. There was usually a slit at one side for the horn of the saddle. So far, these have been reported for the Blackfoot, Sarsi, Crow, Dakota and Cheyenne. They are mentioned as common in the Missouri area by Larpenteur, who implies that the shape is copied after those used by whites. Morice credits the Carrier of the Mackenzie culture area with similar bags used on dogs.

It will be noted that in style and range of bags and pouches, the Village group of these Indians (p. 19) tends to stand apart from the other groups much more distinctly than the intermediate tribes of the west, for between the latter and the typical Plains tribes, there are few marked differences.