It is fortunately possible to produce some illustrations of the modern Neapolitan sign language traced from the plates of De Jorio, with translations, somewhat condensed, of his descriptions and remarks.

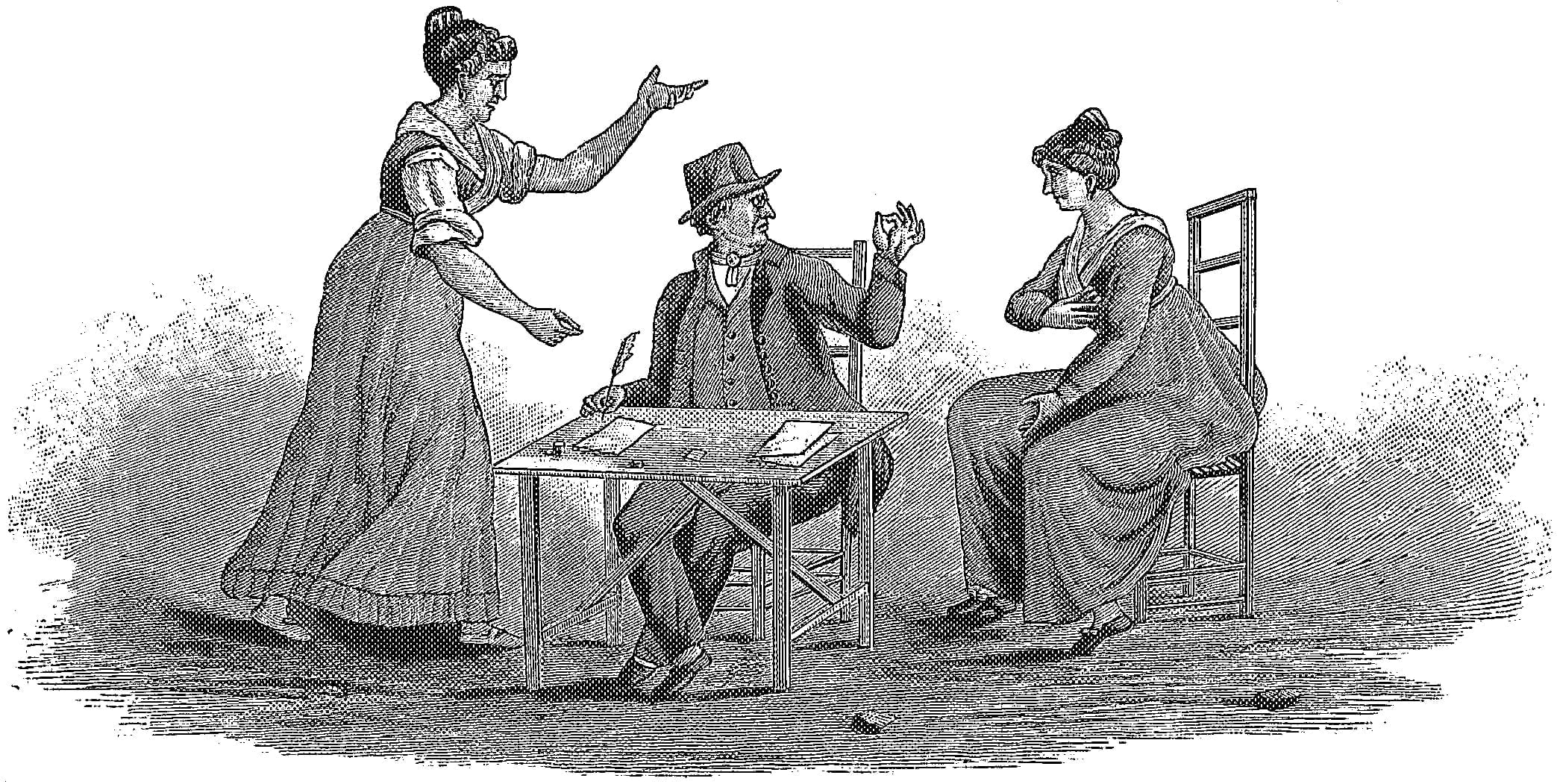

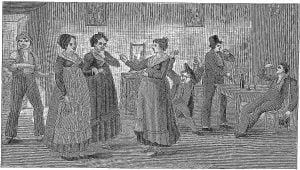

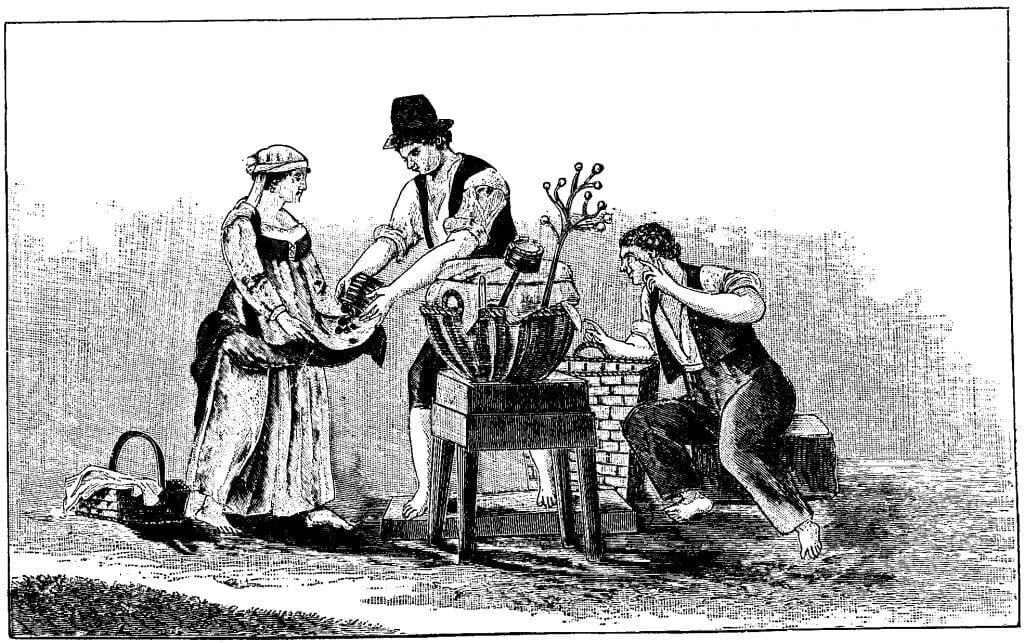

In Fig. 76 an ambulant secretary or public writer is seated at his little table, on which are the meager tools of his trade. He wears spectacles in token that he has read and written much, and has one seat at his side to accommodate his customers. On this is seated a married woman who asks him to write a letter to her absent husband. The secretary, not being told what to write about, without surprise, but somewhat amused, raises his left hand with the ends of the thumb and finger joined, the other fingers naturally open, a common sign for inquiry. “What shall the letter be about?” The wife, not being ready of speech, to rid herself of the embarrassment, resorts to the mimic art, and, without opening her mouth, tells with simple gestures all that is in her mind. Bringing her right hand to her heart, with a corresponding glance of the eyes she shows that the theme is to be love. For emphasis also she curves the whole upper part of her body towards him, to exhibit the intensity of her passion. To complete the mimic story, she makes with her left hand the sign of asking for something, which has been above described (see page 291). The letter, then, is to assure her husband of her love and to beg him to return it with corresponding affection. The other woman, perhaps her sister, who has understood the whole direction, regards the request as silly and fruitless and is much disgusted. Being on her feet, she takes a step toward the wife, who she thinks is unadvised, and raises her left hand with a sign of disapprobation. This position of the hand is described in full as open, raised high, and oscillated from right to left.

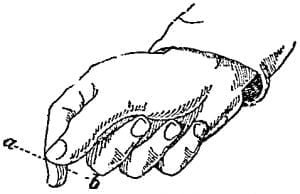

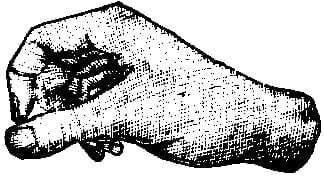

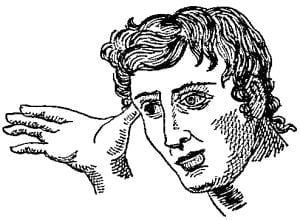

Several of the Indian signs have the same idea of oscillation of the hand raised, often near the head, to express folly, fool. She clearly says, “What a thing to ask! what a fool you are!” and at the same time makes with the right hand the sign of money. This is made by the extremities of the thumb and index rapidly rubbed against each other, and is shown more clearly in Fig. 77.

It is taken from the handling and counting of coin. This may be compared with an Indian sign, see Fig. 115. So the sister is clearly disapproving with her left hand and with her right giving good counsel, as if to say, in the combination, “What a fool you are to ask for his love; you had better ask him to send you some money.”

Gesture of Asking

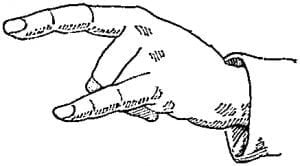

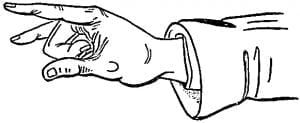

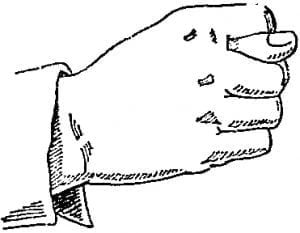

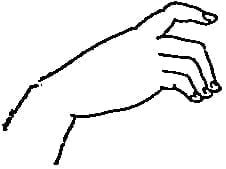

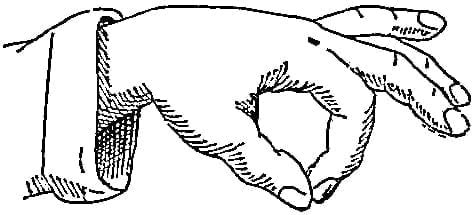

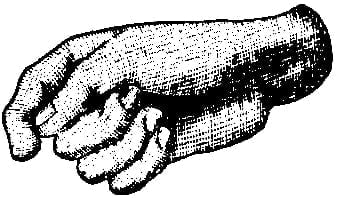

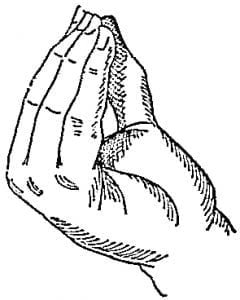

In Naples, as in American cities, boiled ears of green corn are vended with much outcry. Fig. 78 shows a boy who is attracted by the local cry “Pollanchelle tenerelle!” and seeing the sweet golden ears still boiling in the kettle from which steams forth fragrance, has an ardent desire to taste the same, but is without a soldo. He tries begging. His right open hand is advanced toward the desired object with the sign of asking or begging, and he also raises his left forefinger to indicate the number one”Pretty girl, please only give me one!” The pretty girl is by no means cajoled, and while her left hand holds the ladle ready to use if he dares to touch her merchandise, she replies by gesture “Te voglio dà no cuorno!” freely translated, “I’ll give you one in a horn!” This gesture is drawn, with clearer outline in Fig. 79, and has many significations, according to the subject-matter and context, and also as applied to different parts of the body.

Applied to the head it has allusion, descending from high antiquity, to a marital misfortune which was probably common in prehistoric times as well as the present. It is also often used as an amulet against the jettatura or evil eye, and misfortune in general, and directed toward another person is a prayerful wish for his or her preservation from evil. This use is ancient, as is shown on medals and statues, and is supposed by some to refer to the horns of animals slaughtered in sacrifice.

The position of the fingers, Fig. 80, is also given as one of Quintilian’s oratorical gestures by the words “Duo quoque medii sub pollicem veniunt,” and is said by him to be vehement and connected with reproach or argument. In the present case, as a response to an impertinent or disagreeable petition, it simply means, “instead of giving what you ask, I will give you nothing but what is vile and useless, as horns are.”

Disturbance at signing of Neapolitan marriage contract.

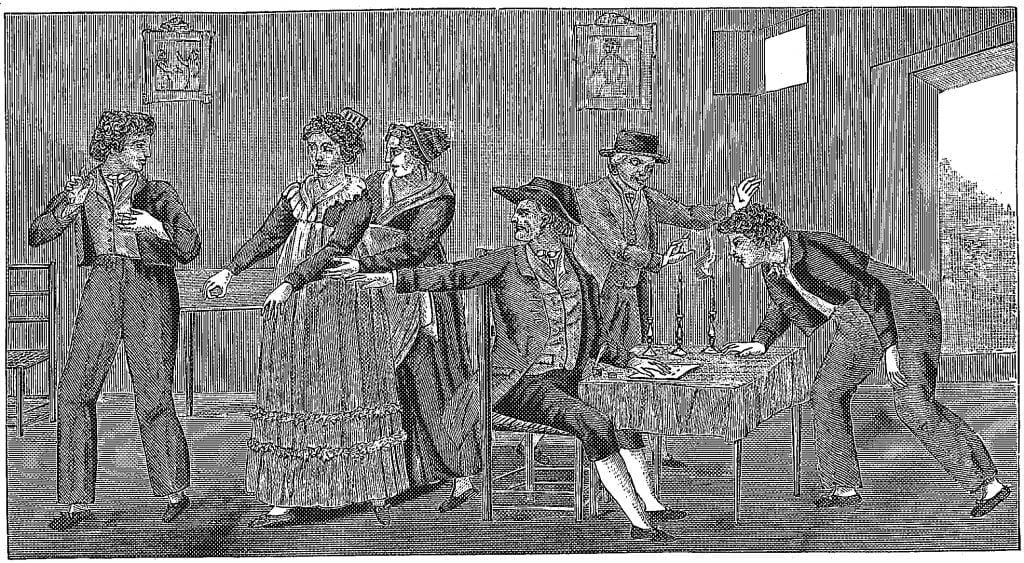

Fig. 81 tells a story which is substantially the foundation of the slender plot of most modern scenic pantomimes preliminary to the bursting forth from their chrysalides of Harlequin, Columbine, Pantaloon, and company. A young girl, with the consent of her parents, has for some time promised her hand to an honest youth. The old mother, in despite of her word, has taken a caprice to give her daughter to another suitor. The father, though much under the sway of his spouse, is in his heart desirous to keep his engagement, and has called in the notary to draw the contract. At this moment the scene begins, the actors of which, for greater perspicuity and brevity, may be provided with stage names as follows:

Cecca, diminutive for Francisca, the mother of –

Nanella, diminutive of Antoniella, the betrothed of –

Peppino, diminutive of Peppe, which is diminutive of Giuseppe.

Pasquale, husband of Cecca and father of Nanella.

Tonno, diminutive of Antonio, favored by Cecca.

D. Alfonso, notary.

Cecca tries to pick a quarrel with Peppino, and declares that the contract shall not be signed. He reminds her of her promise, and accuses her of breach of faith. In her passion she calls on her daughter to repudiate her lover, and casting her arms around her, commands her to make the sign of breaking off friendship”scocchiare“which, she has herself made to Peppino, and which consists in extending the hand with the joined ends of finger and thumb before described, see Fig. 66, and then separating them, thus breaking the union. This the latter reluctantly pretends to do with one hand, yet with the other, which is concealed from her irate mother’s sight, shows her constancy by continuing with emphatic pressure the sign of love. According to the gesture vocabulary, on the sign scocchiare being made to a person who is willing to accept the breach of former affection, he replies in the same manner, or still more forcibly by inserting the index of the other hand between the index and thumb of the first, thus showing the separation by the presence of a material obstacle. Simply refraining from holding out the hand in any responsive gesture is sufficient to indicate that the breach is not accepted, but that the party addressed desires to continue in friendship instead of resolving into enmity. This weak and inactive negative, however, does not suit Peppino’s vivacity, who, placing his left hand on his bosom, makes, with his right, one of the signs for emphatic negation.

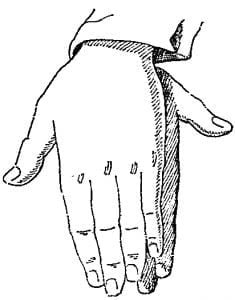

This consists of the palm turned to the person addressed with the index somewhat extended and separated from the other fingers, the whole hand being oscillated from right to left. This gesture appears on ancient Greek vases, and is compound, the index being demonstrative and the negation shown by the horizontal oscillation, the whole being translatable as, “That thing I want not, won’t have, reject.” The sign is virtually the same as that made by Arapaho and Cheyenne Indians (see Extracts from Dictionary, page 440, infra.). The conception of oscillation to show negation also appears with different execution in the sign of the Jicarilla Apaches and the Pai-Utes, Fig. 82. The same sign is reported from Japan, in the same sense.

Tonno, in hopes that the quarrel is definitive, to do his part in stopping the ceremony, proceeds to blow out the three lighted candles, which are an important traditional feature of the rite. The good old man Pasquale, with his hands extended, raised in surprised displeasure and directed toward the insolent youth, stops his attempt. The veteran notary, familiar with such quarrels in his experience, smiles at this one, and, continuing in his quiet attitude, extends his right hand placidly to Peppino with the sign of adagio, before described, see Fig. 68, advising him not to get excited, but to persist quietly, and all would be well.

Fig. 83 portrays the first entrance of a bride to her husband’s house. She comes in with a tender and languid mien, her pendent arms indicating soft yielding, and the right hand loosely holds a handkerchief, ready to apply in case of overpowering emotion. She is, or feigns to be, so timid and embarrassed as to require support by the arm of a friend who introduces her. She is followed by a male friend of the family, whose joyful face is turned toward supposed by-standers, right hand pointing to the new acquisition, while with his left he makes the sign of horns before described, see Fig. 79, which in this connection is to wish prosperity and avert misfortune, and is equivalent to the words in the Neapolitan dialect, “Mal’uocchie non nce pozzano” may evil eyes never have power over her.

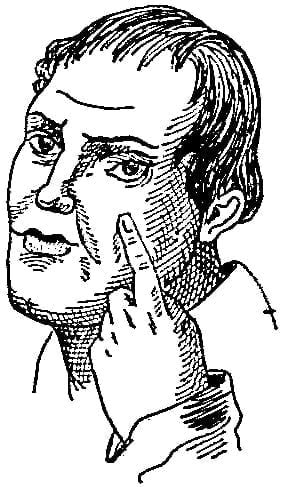

Beautiful

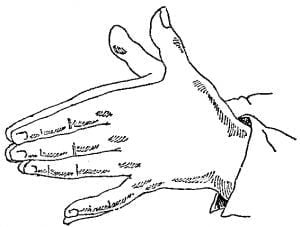

The female confidant, who supports and guides her embarrassed friend with her right arm, brings her left hand into the sign of beautiful” See what a beauty she is!” This sign is made by the thumb and index open and severally lightly touching each side of the lower cheek, the other fingers open. It is given on a larger scale and slightly varied in Fig. 84, evidently referring to a fat and rounded visage. Almost the same sign is made by the Ojibwas of Lake Superior, and a mere variant of it is made by the Dakotasstroking the cheeks alternately down to the tip of the chin with the palm or surface of the extended fingers.

The mother-in-law greets the bride by making the sign mano in fica with her right hand. This sign, made with the hand clenched and the point of the thumb between and projecting beyond the fore and middle fingers, is more distinctly shown in Fig. 85.

Female

It has a very ancient origin, being found on Greek antiques that have escaped the destruction of time, more particularly in bronzes, and undoubtedly refers to the pudendum muliebre. It is used offensively and ironically, but also which is doubtless the case in this instanceas an invocation or prayer against evil, being more forcible than the horn-shaped gesture before described. With this sign the Indian sign for female, see Fig. 132, page 357, infra, may be compared.

The mother-in-law also places her left hand hollowed in front of her abdomen, drawing with it her gown slightly forward, thereby making a pantomimic representation of the state in which “women wish to be who love their lords”; the idea being plainly an expressed hope that the household will be blessed with a new generation.Next to her is a hunchback, who is present as a familiar clown or merrymaker, and dances and laughs to please the company, at the same time snapping his fingers. Two other illustrations of this action, the middle finger in one leaving and in the other having left the thumb and passed to its base, are seen in Figs. 86, 87.

This gesture by itself has, like others mentioned, a great variety of significations, but here means joy and acclamation. It is frequently used among us for subdued applause, less violent than clapping the two hands, but still oftener to express negation with disdain, and also carelessness. Both these uses of it are common in Naples, and appear in Etruscan vases and Pompeian paintings, as well as in the classic authors. The significance of the action in the hand of the contemporary statue of Sardanapalus at Anchiale is clearly worthlessness, as shown by the inscription in Assyrian, “Sardanapalus, the son of Anacyndaraxes, built in one day Anchiale and Tarsus. Eat, drink, play; the rest is not worth that!”

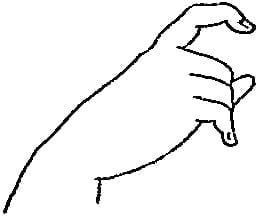

The bridegroom has left his mother to do the honors to the bride, and himself attends to the rest of the company, inviting one of them to drink some wine by a sign, enlarged in Fig. 88, which is not merely pointing to the mouth with the thumb, but the hand with the incurved fingers represents the body of the common glass flask which the Neapolitans use, the extended thumb being its neck; the invitation is therefore specially to drink wine. The guest, however, responds by a very obvious gesture that he don’t wish anything to drink, but he would like to eat some macaroni, the fingers being disposed as if handling that comestible in the fashion of vulgar Italians. If the idea were only to eat generally, it would have been expressed by the fingers and thumb united in a point and moved several times near and toward the mouth, not raised above it, as is necessary for suspending the strings of macaroni.

In Fig. 89 the female in the left of the group is much disgusted at seeing one of her former acquaintances, who has met with good fortune, promenade in a fine costume with her husband. Overcome with jealousy, she spreads out her dress derisively on both sides, in imitation of the hoop-skirts once worn by women of rank, as if to say “So you are playing the great lady!” The insulted woman, in resentment, makes with both hands, for double effect, the sign of horns, before described, which in this case is done obviously in menace and imprecation. The husband is a pacific fellow who is not willing to get into a woman’s quarrel, and is very easily held back by a woman and small boy who happen to join the group. He contents himself with pretending to be in a great passion and biting his finger, which gesture may be collated with the emotional clinching of the teeth and biting the lips in anger, common to all mankind.

Warning Against a Cheat

The cheating Neapolitan chestnut huckster. In Fig. 90 a contadina, or woman from the country, who has come to the city to sell eggs (shown to be such by her head-dress, and the form of the basket which she has deposited on the ground), accosts a vender of roast chestnuts and asks for a measure of them. The chestnut huckster says they are very fine and asks a price beyond that of the market; but a boy sees that the rustic woman is not sharp in worldly matters and desires to warn her against the cheat. He therefore, at the moment when he can catch her eye, pretending to lean upon his basket, and moving thus a little behind the huckster, so as not to be seen, points him out with his index finger, and lays his left forefinger under his eye, pulling down the skin slightly, so as to deform the regularity of the lower eyelid. This is a warning against a cheat, shown more clearly in Fig. 91.

This sign primarily indicates a squinting person, and metaphorically one whose looks cannot be trusted, even as in a squinting person you cannot be certain in which direction he is looking.

Fig. 92 shows the extremities of the index and thumb closely joined in form of a cone, and turned down, the other fingers held at pleasure, and the hand and arm advanced to the point and held steady. This signifies justice, a just person, that which is just and right. The same sign may denote friendship, a menace, which specifically is that of being brought to justice, and snuff, i.e. powdered tobacco; but the expression of the countenance and the circumstance of the use of the sign determine these distinctions. Its origin is clearly the balance or emblem of justice, the office of which consists in ascertaining physical weight, and thence comes the moral idea of distinguishing clearly what is just and accurate and what is not. The hand is presented in the usual manner of holding the balance to weigh articles.

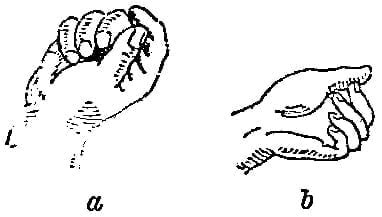

Little, Small

Fig. 93 signifies little, small, both as regards the size of physical objects or figuratively, as of a small degree of talent, affection, or the like. It is made either by the point of the thumb placed under the end of the index (a), or vice versa (b), and the other fingers held at will, but separated from those mentioned. The intention is to exhibit a small portion either of the thumb or index separated from the rest of the hand. The gesture is found in Herculanean bronzes, with obviously the same signification. The signs made by some tribes of Indians for the same conception are very similar, as is seen by Figs. 94 and 95.

Fig. 96 is simply the index extended by itself. The other fingers are generally bent inwards and pressed down by the thumb, as mentioned by Quintilian, but that is not necessary to the gesture if the forefinger is distinctly separated from the rest. It is most commonly used for indication, pointing out, as it is over all the world, from which comes the name index, applied by the Romans as also by us, to the forefinger. In different relations to the several parts of the body and arm positions it has many significations, e.g., attention, meditation, derision, silence, number, and demonstration in general.

Fig. 97 represents the head of a jackass, the thumbs being the ears, and the separation of the little from the third fingers showing the jaws.

Stupid, Fool

Fig. 98 is intended to portray the head of the same animal in a front view, the hands being laid upon each other, with thumbs extending on each side to represent the ears. In each case the thumbs are generally moved forward and back, in the manner of the quadruped, which, without much apparent reason, has been selected as the emblem of stupidity. The sign, therefore, means stupid, fool. Another mode of executing the same conceptionthe ears of an assis shown in Fig. 99, where the end of the thumb is applied to the ear or temple and the hand is wagged up and down. Whether the ancient Greeks had the same low opinion of the ass as is now entertained is not clear, but they regarded long ears with derision, and Apollo, as a punishment to Midas for his foolish decision, bestowed on him the lengthy ornaments of the patient beast.

Inquiry

Fig. 100 is the fingers elongated and united in a point, turned upwards. The hand is raised slightly toward the face of the gesturer and shaken a few times in the direction of the person conversed with. This is inquiry, not a mere interrogative, but to express that the person addressed has not been clearly understood, perhaps from the vagueness or diffusiveness of his expressions. The idea appears to suggest the gathering of his thoughts together into one distinct expression, or to be pointed in what he wishes to say.

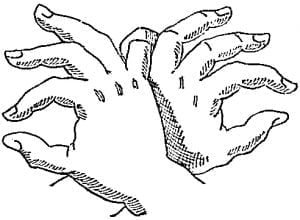

Crafty, Deceitful

Crafty, deceitful, Fig. 101. The little fingers of both reversed hands are hooked together, the others open but slightly curved, and, with the hands, moved several times to the right and left. The gesture is intended to represent a crab and the tortuous movements of the crustacean, which are likened to those of a man who cannot be depended on in his walk through life. He is not straight.

Figs. 102 and 103 are different positions of the hand in which the approximating thumb and forefinger form a circle. This is the direst insult that can be given. The amiable canon De Jorio only hints at its special significance, but it may be evident to persons aware of a practice disgraceful to Italy. It is very ancient.

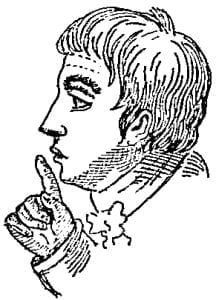

Silent

Fig. 104 is easily recognized as a request or command to be silent, either on the occasion or on the subject. The mouth, supposed to be forcibly closed, prevents speaking, and the natural gesture, as might be supposed, is historically ancient, but the instance, frequently adduced from the attitude of the god Harpokrates, whose finger is on his lips, is an error. The Egyptian hieroglyphists, notably in the designation of Horus, their dawn-god, used the finger in or on the lips for “child.” It has been conjectured in the last instance that the gesture implied, not the mode of taking nourishment, but inability to speakin-fans. This conjecture, however, was only made to explain the blunder of the Greeks, who saw in the hand placed connected with the mouth in the hieroglyph of Horus (the) son, “Hor-(p)-chrot,” the gesture familiar to themselves of a finger on the lips to express “silence,” and so, mistaking both the name and the characterization, invented the God of Silence, Harpokrates. A careful examination of all the linear hieroglyphs given by Champollion (Dictionnaire Egyptien) shows that the finger or the hand to the mouth of an adult (whose posture is always distinct from that of a child) is always in connection with the positive ideas of voice, mouth, speech, writing, eating, drinking, &c., and never with the negative idea of silence. The special character for child, Fig. 105, always has the above-mentioned part of the sign with reference to nourishment from the breast.

Negation

Fig. 106 is a forcible negation. The outer ends of the fingers united in a point under the chin are violently thrust forward. This is the rejection of an idea or proposition, the same conception being executed in several different modes by the North American Indians.

Hunger

Fig. 107 signifies hunger, and is made by extending the thumb and index under the open mouth and turning them horizontally and vertically several times.

The idea is emptiness and desire to be filled. It is also expressed by beating the ribs with the flat hands, to show that the sides meet or are weak for the want of something between them.

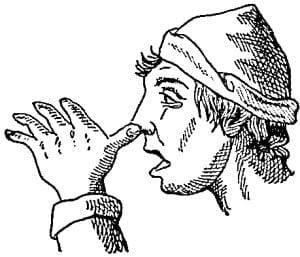

Mocking, Ridicule

Fig. 108 is made in mocking and ridicule. The open and oscillating hand touches the point of the nose with that of the thumb. It has the particular sense of stigmatizing the person addressed or in question as a dupe. A credulous person is generally imagined with a gaping mouth and staring eyes, and as thrusting forward his face, with pendant chin, so that the nose is well advanced and therefore most prominent in the profile. A dupe is therefore called naso lungo or long-nose, and with Italian writers “restare con un palmo di naso“to be left with a palm’s length of nosemeans to have met with loss, injury, or disappointment.

Fatigue

The thumb stroking the forehead from one side to the other, Fig. 109, is a natural sign of fatigue, and of the physical toil that produces fatigue. The wiping off of perspiration is obviously indicated. This gesture is often used ironically.

A Dupe

As a dupe was shown above, now the duper is signified, by Fig. 110.

The gesture is to place the fingers between the cravat and the neck and rub the latter with the back of the hand. The idea is that the deceit is put within the cravat, taken in and down, similar to our phrase to “swallow” a false and deceitful story, and a “cram” is also an English slang word for an incredible lie. The conception of the slang term is nearly related to that of the Neapolitan sign, viz., the artificial enlargement of the sophagus of the person victimized or on whom imposition is attempted to be practiced, which is necessary to take it down.

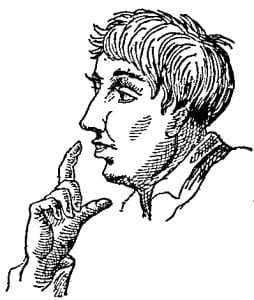

Astute, Attentive, Ready

Fig. 111 shows the ends of the index and thumb stroking the two sides of the nose from base to point. This means astute, attentive, ready. Sharpness of the nasal organ is popularly associated with subtlety and finesse. The old Romans by homo emunctæ naris meant an acute man attentive to his interests. The sign is often used in a bad sense, then signifying toosharp to be trusted.This somewhat lengthy but yet only partial list of Neapolitan gesture-signs must conclude with one common throughout Italy, and also among us with a somewhat different signification, yet perhaps also derived from classic times. To express suspicion of a person the forefinger of the right hand is placed upon the side of the nose. It means tainted, not sound. It is used to give an unfavorable report of a person inquired of and to warn against such.

Chinese

The Chinese, though ready in gesticulation and divided by dialects, do not appear to make general use of a systematic sign language, but they adopt an expedient rendered possible by the peculiarity of their written characters, with which a large proportion of their adults are acquainted, and which are common in form to the whole empire. The inhabitants of different provinces when meeting, and being unable to converse orally, do not try to do so, but write the characters of the words upon the ground or trace them on the palm of the hand or in the air. Those written characters each represent words in the same manner as do the Arabic or Roman numerals, which are the same to Italians, Germans, French, and English, and therefore intelligible, but if expressed in sound or written in full by the alphabet, would not be mutually understood. This device of the Chinese was with less apparent necessity resorted to in the writer’s personal knowledge between a Hungarian who could talk Latin, and a then recent graduate from college who could also do so to some extent, but their pronunciation was so different as to occasion constant difficulty, so they both wrote the words on paper, instead of attempting to speak them.The efforts at intercommunication of all savage and barbarian tribes, when brought into contact with other bodies of men not speaking an oral language common to both, and especially when uncivilized inhabitants of the same territory are separated by many linguistic divisions, should in theory resemble the devices of the North American Indians. They are not shown by published works to prevail in the Eastern hemisphere to the same extent and in the same manner as in North America. It is, however, probable that they exist in many localities, though not reported, and also that some of them survive after partial or even high civilization has been attained, and after changed environment has rendered their systematic employment unnecessary. Such signs may be, first, unconnected with existing oral language, and used in place of it; second, used to explain or accentuate the words of ordinary speech, or third, they may consist of gestures, emotional or not, which are only noticed in oratory or impassioned conversation, being, possibly, survivals of a former gesture language.From correspondence instituted it may be expected that a considerable collection of signs will be obtained from West and South Africa, India, Arabia, Turkey, the Fiji Islands, Sumatra, Madagascar, Ceylon, and especially from Australia, where the conditions are similar in many respects to those prevailing in North America prior to the Columbian discovery. In the Aborigines of Victoria, Melbourne, 1878, by R. Brough Smythe, the author makes the following curious remarks: “It is believed that they have several signs, known only to themselves, or to those among the whites who have had intercourse with them for lengthened periods, which convey information readily and accurately. Indeed, because of their use of signs, it is the firm belief of many (some uneducated and some educated) that the natives of Australia are acquainted with the secrets of Freemasonry.”

In the Report of the cruise of the United States Revenue steamer Corwin in the Arctic Ocean, Washington, 1881, it appears that the Innuits of the northwestern extremity of America use signs continually. Captain Hooper, commanding that steamer, is reported by Mr. Petroff to have found that the natives of Nunivak Island, on the American side, below Behring Strait, trade by signs with those of the Asiatic coast, whose language is different. Humboldt in his journeyings among the Indians of the Orinoco, where many small isolated tribes spoke languages not understood by any other, found the language of signs in full operation. Spix and Martius give a similar account of the Puris and Coroados of Brazil.

Signs of deaf-mutes

It is not necessary to enlarge under the present heading upon the signs of deaf-mutes, except to show the intimate relation between sign language as practiced by them and the gesture signs, which, even if not “natural,” are intelligible to the most widely separated of mankind. A Sandwich Islander, a Chinese, and the Africans from the slaver Amistad have, in published instances, visited our deaf-mute institutions with the same result of free and pleasurable intercourse; and an English deaf-mute had no difficulty in conversing with Laplanders. It appears, also, on the authority of Sibscota, whose treatise was published in 1670, that Cornelius Haga, ambassador of the United Provinces to the Sublime Porte, found the Sultan’s mutes to have established a language among themselves in which they could discourse with a speaking interpreter, a degree of ingenuity interfering with the object of their selection as slaves unable to repeat conversation. A curious instance has also been reported to the writer of operatives in a large mill where the constant rattling of the machinery rendered them practically deaf during the hours of work and where an original system of gestures was adopted.

In connection with the late international convention, at Milan, of persons interested in the instruction of deaf-mutes which, in the enthusiasm of the members for the new system of artificial articulate speech, made war upon all gesture-signs, it is curious that such prohibition of gesture should be urged regarding mutes when it was prevalent to so great an extent among the speaking people of the country where the convention was held, and when the advocates of it were themselves so dependent on gestures to assist their own oratory if not their ordinary conversation. Artificial articulation surely needs the aid of significant gestures more, when in the highest perfection to which it can attain, than does oral speech in its own high development. The use of artificial speech is also necessarily confined to the oral language acquired by the interlocutors and throws away the advantage of universality possessed by signs.