Though written characters are generally associated with speech, they are shown, by successful employment in hieroglyphs and by educated deaf-mutes to be representative of ideas without the intervention of sounds, and so also are the outlines of signs. This will be more apparent if the motions expressing the most prominent feature, attribute, or function of an object are made, or supposed to be made, so as to leave a luminous track impressible upon the eye separate from the members producing it. The actual result is an immateriate graphic representation of visible objects and qualities which, invested with substance, has become familiar to us as the rebus, and also appears in the form of heraldic blazonry styled punning or “canting.”

Gesture language is, in fact, not only a picture language, but is actual writing, though dissolving and sympathetic, and neither alphabetic nor phonetic.

Dalgarno aptly says: “Qui enim caput nutat, oculo connivet, digitum movet in aëre, &c., (ad mentis cogitata exprimendum); is non minus vere scribit, quam qui Literas pingit in Charta, Marmore, vel ære.”

It is neither necessary nor proper to enter now upon any prolonged account of the origin, of alphabetic writing. There is, however, propriety, if not necessity, for the present writer, when making any remarks under this heading and under some others in this paper indicating special lines of research, to disclaim all pretension to being a Sinologue or Egyptologist, or even profoundly versed in Mexican antiquities. His partial and recently commenced studies only enable him to present suggestions for the examination of scholars. These suggestions may safely be introduced by the statement that the common modern alphabetic characters, coming directly from the Romans, were obtained by them from the Greeks, and by the latter from the Phœnicians, whose alphabet was connected with that of the old Hebrew. It has also been of late the general opinion that the whole family of alphabets to which the Greek, Latin, Gothic, Runic, and others belong, appearing earlier in the Phœnician, Moabite, and Hebrew, had its beginning in the ideographic pictures of the Egyptians, afterwards used by them to express sounds. That the Chinese, though in a different manner from the Egyptians, passed from picture writing to phonetic writing, is established by delineations still extant among them, called ku-wăn, or “ancient pictures,” with which some of the modern written characters can be identified. The ancient Mexicans also, to some extent, developed phonetic expressions out of a very elaborate system of ideographic picture writing. Assuming that ideographic pictures made by ancient peoples would be likely to contain representations of gesture signs, which subject is treated of below, it is proper to examine if traces of such gesture signs may not be found in the Egyptian, Chinese, and Aztec characters. Only a few presumptive examples, selected from a considerable number, are now presented in which the signs of the North American Indians appear to be included, with the hope that further investigation by collaborators will establish many more instances not confined to Indian signs.

No / Negation / None / Nothing

A typical sign made by the Indians for no, negation, is as follows: The hand extended or slightly curved is held in front of the body, a little to the right of the median line; it is then carried with a rapid sweep a foot or more farther to the right. (Mandan and Hidatsa I.)

One for none, nothing, sometimes used for simple negation, is also given: Throw both hands outward toward their respective sides from the breast. (Wyandot I.)

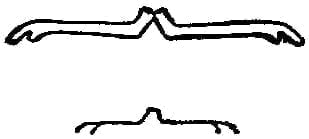

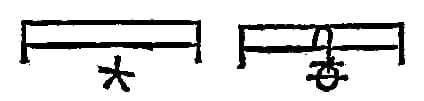

With these compare the two forms of the Egyptian character for no, negation, Fig. 118, taken from Champollion, Grammaire Égyptienne, Paris, 1836, p. 519.

No vivid fancy is needed to see the hands indicated at the extremities of arms extended symmetrically from the body on each side.

Also compare the Maya character for the same idea of negation, Fig. 119, found in Landa, Relation des Choses de Yucatan, Paris, 1864, 316. The Maya word for negation is “ma,” and the word “mak,” a six-foot measuring rod, given by Brasseur de Bourbourg in his dictionary, apparently having connection with this character, would in use separate the hands as illustrated, giving the same form as the gesture made without the rod.

Another sign for nothing, none, made by the Comanches, is: Flat hand thrown forward, back to the ground, fingers pointing forward and downward. Frequently the right hand is brushed over the left thus thrown out.

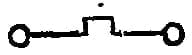

Compare the Chinese character for the same meaning, Fig. 120. This will not be recognized as a hand without study of similar characters, which generally have a cross-line cutting off the wrist. Here the wrist bones follow under the cross cut, then the metacarpal bones, and last the fingers, pointing forward and downward.

Child

The Arapaho sign for child, baby, is the forefinger in the mouth, i.e., a nursing child, and a natural sign of a deaf-mute is the same. The Egyptian figurative character for the same is seen in Fig. 121. Its linear form is Fig. 122, and its hieratic is Fig. 123 (Champollion, Dictionnaire Egyptien, Paris, 1841, p. 31.)

Son, Birth

These afford an interpretation to the ancient Chinese form for son, Fig. 124, given in Journ. Royal Asiatic Society, I, 1834, p. 219, as belonging to the Shang dynasty, 1756, 1112 B.C., and the modern Chinese form, Fig. 125, which, without the comparison, would not be supposed to have any pictured reference to an infant with hand or finger at or approaching the mouth, denoting the taking of nourishment.

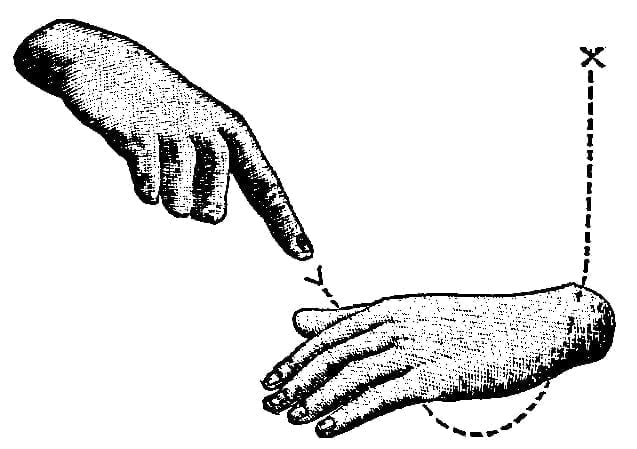

Having now suggested this, the Chinese character for birth, Fig. 126, is understood as the expression of a common gesture among the Indians, particularly reported from the Dakota, for born, to be born, viz:

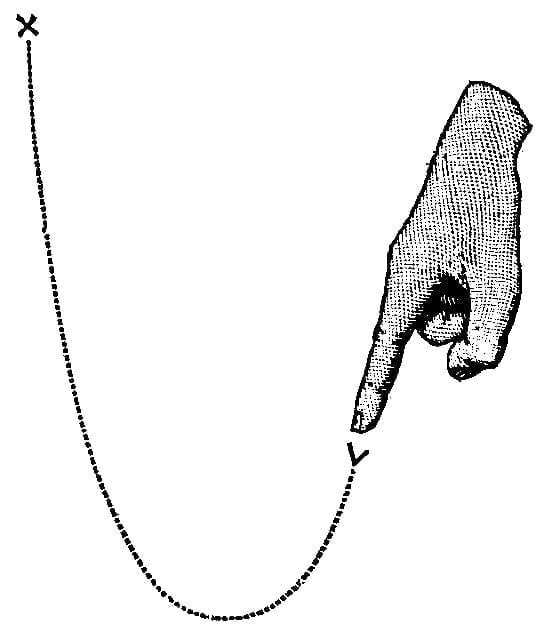

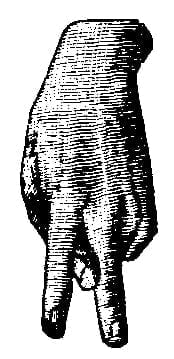

Place the left hand in front of the body, a little to the right, the palm downward and slightly arched, then pass the extended right hand downward, forward, and upward, forming a short curve underneath the left, as in Fig. 127 (Dakota V). This is based upon the curve followed by the head of the child during birth, and is used generically. The same curve, when made with one hand, appears in Fig. 128.

It may be of interest to compare with the Chinese child the Mexican [pg 357] abbreviated character for man, Fig. 129, found in Pipart in Compte Rendu Cong. Inter. des Américanistes, 2me Session, Luxembourg, 1877, 1878, II, 359. The figure on the right is called the abbreviated form of that by its side, yet its origin may be different.

Man, Woman, Female

The Chinese character for man, is Fig. 130, and may have the same obvious conception as a Dakota sign for the same signification: “Place the extended index, pointing upward and forward before the lower portion of the abdomen.”

The Chinese specific character for woman is Fig. 131, the cross mark denoting the wrist, and if the remainder be considered the hand, the fingers may be imagined in the position made by many tribes, and especially the Utes, as depicting the pudendum muliebre, Fig. 132.

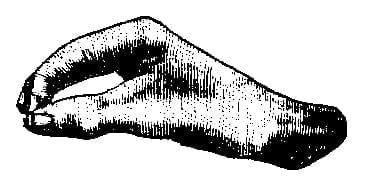

The Egyptian generic character for female is ![]() (Champollion, Dict.,) believed to represent the curve of the mammæ supposed to be cut off or separated from the chest, and the gesture with the same meaning was made by the Cheyenne Titchkematski, and photographed, as in Fig. 133. It forms the same figure as the Egyptian character as well as can be done by a position of the human hand.

(Champollion, Dict.,) believed to represent the curve of the mammæ supposed to be cut off or separated from the chest, and the gesture with the same meaning was made by the Cheyenne Titchkematski, and photographed, as in Fig. 133. It forms the same figure as the Egyptian character as well as can be done by a position of the human hand.

The Chinese character for to give water is Fig. 134, which may be compared with the common Indian gesture to drink, to give water, viz: “Hand held with tips of fingers brought together and passed to the mouth, as if scooping up water”, Fig. 135, obviously from the primitive custom, as with Mojaves, who still drink with scooped hands.

Water / To Drink, Stream

Another common Indian gesture sign for water to drink, I want to drink, is: “Hand brought downward past the mouth with loosely extended fingers, palm toward the face.” This appears in the Mexican character for drink, Fig. 136, taken from Pipart, loc. cit., p. 351. Water, i.e., the pouring out of water with the drops falling or about to fall, is shown in Fig. 137, taken from the same author (p. 349), being the same arrangement of them as in the sign for rain, Fig. 114, p. 344, the hand, however, being inverted. Rain in the Mexican picture writing is shown by small circles inclosing a dot, as in the last two figures, but not connected together, each having a short line upward marking the line of descent.

With the gesture for drink may be compared Fig. 138, the Egyptian Goddess Nu in the sacred sycamore tree, pouring out the water of life to the Osirian and his soul, represented as a bird, in Amenti (Sharpe, from a funereal stele in the British Museum, in Cooper’s Serpent Myths, p. 43).

The common Indian gesture for river or stream, water, is made by passing the horizontal flat hand, palm down, forward and to the left from the right side in a serpentine manner.

The Egyptian character for the same is Fig. 139 (Champollion, Dict., p. 429). The broken line is held to represent the movement of the water on the surface of the stream. When made with one line less angular and more waving it means water. It is interesting to compare with this the identical character in the syllabary invented by a West African negro, Mormoru Doalu Bukere, for water, ![]() , mentioned by Tylor in his Early History of Mankind, p. 103.

, mentioned by Tylor in his Early History of Mankind, p. 103.

The abbreviated Egyptian sign for water as a stream is Fig. 140 (Champollion, loc. cit.), and the Chinese for the same is as in Fig. 141.

In the picture-writing of the Ojibwa the Egyptian abbreviated character, with two lines instead of three, appears with the same signification.

Weep, Force, Vigot

The Egyptian character for weep, Fig. 142, an eye, with tears falling, is also found in the pictographs of the Ojibwa (Schoolcraft, I, pl. 54, Fig. 27), and is also made by the Indian gesture of drawing lines by the index repeatedly downward from the eye, though perhaps more frequently made by the full sign for rain, described on page 344, made with the back of the hand downward from the eye—”eye rain.”

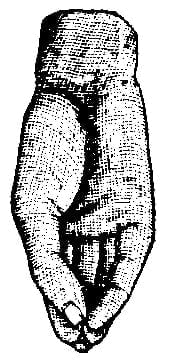

The Egyptian character for to be strong is Fig. 143 (Champollion, Dict., p. 91), which is sufficiently obvious, but may be compared with the sign for strong, made by some tribes as follows: Hold the clinched fist in front of the right side, a little higher than the elbow, then throw it forcibly about six inches toward the ground.

Night

A typical gesture for night is as follows: Place the flat hands, horizontally, about two feet apart, move them quickly in an upward curve toward one another until the right lies across the left. “Darkness covers all.” See Fig. 312, page 489.

The conception of covering executed by delineating the object covered beneath the middle point of an arch or curve, appears also clearly in the Egyptian characters for night, Fig. 144 (Champollion, Dict., p. 3). The upper part of the character is taken separately to form that for sky (see page 372, infra).

Calling Upon

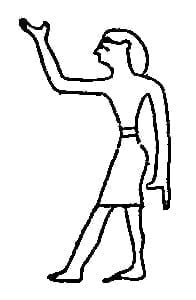

The Egyptian figurative and linear characters, Figs. 145 and 146 (Champollion, Dict., p. 28), for calling upon and invocation, also used as an interjection, scarcely require the quotation of an Indian sign, being common all over the world.

To collect, To Unite

The gesture sign made by several tribes for many is as follows: Both hands, with spread and slightly curved fingers, are held pendent about two feet apart before the thighs; then bring them toward one another, horizontally, drawing them upward as they come together. (Absaroka I; Shoshoni and Banak I; Kaiowa I; Comanche III; Apache II; Wichita II.) “An accumulation of objects.” This may be the same motion indicated by the Egyptian character, Fig. 147, meaning to gather together (Champollion, Dict., p. 459).

Locomotion

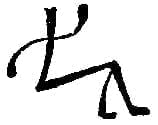

The Egyptian character, Fig. 148, which in its linear form is represented in Fig. 149, and meaning to go, to come, locomotion, is presented to show readers unfamiliar with hieroglyphics how a corporeal action may be included in a linear character without being obvious or at least certain, unless it should be made clear by comparison with the full figurative form or by other means. This linear form might be noticed many times without certainty or perhaps suspicion that it represented the human legs and feet in the act of walking. The same difficulty, of course, as also the same prospect of success by careful research, attends the tracing of other corporeal motions which more properly come under the head of gesture signs.