The Calendar History of the Kiowa Indians is a work of over 300 pages and is an original contribution of the highest value to ethnography. Its title affords but an imperfect idea of its scope; for, in addition to an elaborate description of the Kiowa calendars, the author gives us, in 106 pages, a sketch of the tribe including its documentary history, a list of western military and trading posts, an extensive glossary of the Kiowa language, and other items of information which lead to a thorough understanding of the calendars.

The pictorial calendars which Mr Mooney describes have many characteristics in common with the Dakota calendars published in previous reports of the Bureau of Ethnology. They do not cover so long a period of time as the Dakota calendar of Lone-dog, — the latter includes seventy-one years, while the Kiowa calendars include but sixty, — yet the Kiowa records are in one respect much the superior, as they give two historic items for each year, instead of one like the Dakota records. They show a summer event and a winter event. As our year begins in winter it is often difficult or impossible to tell in which year, according to our reckoning, the event symbolized in the calendar occurred; but there need be no doubt about the summer events of the Kiowa. There are symbols to indicate the season.

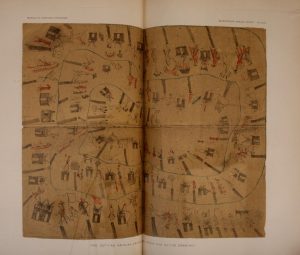

In addition to the four annual calendars described, there is a monthly calendar covering a period of three years. The author of this calendar, Anko, after giving a copy of his work to Mr Mooney, continued his record, and it will interest the faculty to learn that he made it largely a clinical history of the case of his consumptive wife. So far this is the only monthly calendar discovered among the North American tribes.

It is notable how well these pictorial stories of the Kiowa are often corroborated by our own historical records.

The whole work has been painstakingly performed. It exhibits, like all of the author’s works, the results of patient, scholarly research expressed in clear, concise language. It is a mine of valuable information; yet there are a few unimportant points on which we venture to differ with the author, if for no better reason than to air our own knowledge and show that we have actually read the book.

On page 142 the credit for discovering the Lone-dog winter count, which really belongs to Lieutenant Reed, is given to Colonel Mallery. This is merely an oversight on the part of the author. From conversations and correspondence we have had with him, we are aware that, before writing this book, he knew well the history of this “winter count ” and probably saw it before Colonel Mallery did. It is not certain that “The tobacco upon the head of the ancient taime is another evidence of the northern origin of the Kiowa ” (p. 240), since, in prehistoric days Indians of the south and southwest cultivated, or culled in a wild state, different species of Nicotiana. It is not probable that the officer who, in 1867—’68, ” wore upon his shoulders the eagle or thunderbird ” was General Winfield S. Hancock as here stated (p. 320) since the eagle designates the rank of colonel.

The list of “military and trading posts, missions, etc.,” has evidently been compiled with great care, yet from our own personal experience, without reference to any authorities, we are able to correct the dates in three cases. The period of military occupancy of Fort Union, Montana, was 1864-65, not 1867 as given in the list. It was our lot to serve with U. S. Volunteers there in 1865 and to come away with them when they abandoned the post. It was never garrisoned by troops after that; but was razed soon after Fort Buford was established in 1866. Fort Berthold, in what is now North Dakota, was first occupied by troops in 1864, not 1865 as given. The list tells us that Fort Pierre, South Dakota, was occupied by troops in 1865-67; but in the former year we saw it in ruins, with little left to mark the site save a few standing chimneys. We know that no troops were even camped in its neighborhood during the years mentioned.

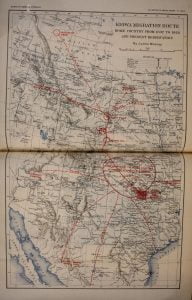

The two excellent maps are very instructive, showing lands and nations known in old days to the Kiowa, and various wanderings of the tribe in their migrations, trading expeditions, friendly visits, and war excursions, on foot and on horseback, before the advent of railroads made long excursions easy. The wanderings cover an area of about 2000 miles from north to south and two from east to west.

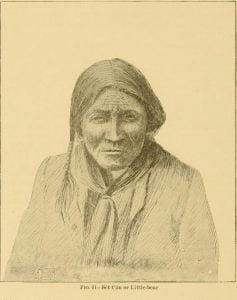

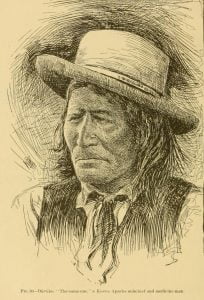

The illustrations are numerous and well chosen, and the work is presented in the excellent form characteristic of the publications of the Bureau of American Ethnology. We regret we cannot speak so well of the binding. Handled with care, the book fell to pieces while we were reading it.

Washington Matthews

Kiowa Photos and Maps

Source: Calendar History of the Kiowa Indians by James Mooney. Seventeenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Part 1. Washington: 1898. Pages 129-445, plates and figures.