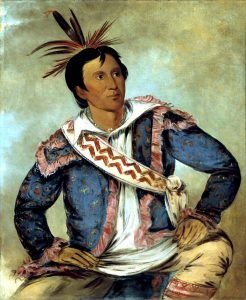

Push-ma-ta-ha – Pushmataha (Apushim-alhtaha, ‘the sapling is ready, or finished, for him.’ Halvert).

A noted Choctaw, of unknown ancestry 1, born on the east bank of Noxuba Creek in Noxubee County, Mississippi in 1764; died at Washington D.C., Dec 24, 1824. before he was 20 years of age he distinguished himself in an expedition against the Osage, west of the Mississippi. The boy disappeared early in a conflict that lasted all day, and on rejoining the Choctaw warriors was jeered at and accused of cowardice, whereon Push-ma-ta-ha replied “Let those laugh who can show more scalps than I can,” forthwith producing five scalps, which he threw upon the ground the result of a single-handed onslaught on the enemy’s rear. This incident gained for him the name “Eagle” and won for hint a chieftaincy; later he became mingo of the Oklahannali or Six Towns district of the Choctaw, and exercised much influence in promoting friendly relations with the whites. Although generally victorious, Push-ma-ta-ha’s war party on one occasion was attacked by a number of Cherokee and defeated. He is said to have moved into the present Texas, then Spanish territory, where he lived several years, adding to his reputation for prowess, on one occasion going alone at night to a Tonaqua (Tawakoni?) village, killing seven men with his own hand, and setting fire to several houses.

During the next two years he made three more expeditions against the same people, adding eight scalps to his trophies. When Tecumseh visited the Choctaw in 1811 to persuade them to join in an uprising against the Americans, Push-ma-ta-ha strongly opposed the movement, and it was largely through his influence that the Shawnee chief’s mission among this tribe failed. During the War of 1812 most of the Choctaw became friendly to the United States through the opposition of Push-ma-ta-ha and John Pitchlynn to a neutral course, Push-ma-ta-ha being alleged to have said, on the last day of a ten days’ council: “The Creeks were once our friends. They have joined the English and we must now follow different trails. When our fathers took the hand of Washington, they told him the Choctaw would always be friends of his nation, and Push-ma-ta-ha can not be false to their promises. I am now ready to fight against both the English and the Creeks.” He was at the head of 500 warriors during the war, engaging in 24 fights and serving under Jackson’s eye in the Pensacola campaign. In 1813, with about 150 Choctaw warriors, he joined Gen. Claiborne and distinguished himself in the attack and defeat of the Creeks under Weatherford at Kantchati, or Holy Ground, on Alabama River, Alabama.

While aiding the United States troops he was so rigid in his discipline that he soon succeeded in converting his wild warriors into efficient soldiers, while for his energy in fighting the Creeks and Seminole he became popularly known to the whites as “The Indian General.”

Push-ma-ta-ha signed the treaties of Nov. 16, 1805; Oct. 24, 1816; and Oct. 18, 1820. In negotiating the last treaty, at Doak’s Stand, “he displayed much diplomacy and showed a business capacity equal to that of Gen. Jackson, against whom he was pitted, in driving a sharp bargain.” In 1824 he went to Washington to negotiate another treaty in behalf of his tribe. Following a brief visit to Lafayette, then at the capital, Push-ma-ta-ha became ill and died within 24 hours. In accordance with his request he was buried with military honors, a procession of 2,000 persons, military and civilian, accompanied by President Jackson, following his remains to Congressional Cemetery. A shaft bearing the following inscriptions was erected over his grave: “Push-ma-ta-ha a Choctaw chief lies here. This monument to his memory is erected by his brother chiefs who were associated with him in a delegation from their nation, in the year 1824, to the General Government of the United States.” ” Push-ma-taha was a warrior of great distinction. He was wise in council, eloquent in an extraordinary degree, and on all occasions, and under all circumstances, the white man’s friend.” “He died in Washington, on the 24th of December, 1824, of the croup, in the 60th year of his age.” General Jackson frequently expressed the opinion that Push-ma-ta-ha was the greatest and the bravest Indian he had ever known, and John Randolph of Roanoke, in pronouncing a eulogy on him in the Senate, uttered the words regarding his wisdom, his eloquence, and his friendship for the whites that afterward were inscribed on his monument. There is good reason to believe, however, that much of Push-ma-ta-ha’s reputation for eloquence was due in no small part to his interpreters. He was deeply interested in the education of his people, and it is said devoted $2,000 of his annuity for fifteen years toward the support of the Choctaw school system. As mingo of the Oklahannali, Push-ma-ta-ha was succeeded by Nittakechi, “Day-prolonger.” Several portraits of Push-ma-ta-ha are extant, including one in the Redwood Library at Newport, R. I., one in possession of Gov. McCurtin at Kinta, Okla. (which was formerly in the Choctaw capitol), and another in a Washington restaurant. The first portrait, painted by C. B. King at Washington in 1824, shortly before Push-ma-ta-ha’s death, was burned in the Smithsonian fire of 1865.

Push-ma-ta-ha was born in east Mississippi in 1765, but his dominion embraced our southwestern counties. The name Push-ma-ta-ha means “He has won all the honors of his race.” Or all the Indians of pure blood who have a place in American history, he blended more admirable traits in his character than any other. He was intelligent, affable, sagacious, brave, eloquent, witty, and comparatively temperate, and, like Logan, he was truly the friend of the white man.’ When told of the massacre at Fort Mims, he rode to Mobile, in company with Mr. Geo. S. Gaines, and offered his services and those of his tribe to Gen. Flournoy. And when they were accepted, he led a body of his warriors with the expedition of Gen. Claiborne the attack on Econochaca. While on his way to Washington, the last time, he rode through Demopolis, and there asked Col. G. S. Gaines to furnish his nephew with a keg of gunpowder, in the event of his death, so that suitable honors might be paid to his memory as a chief and a warrior. He died in Washington a few weeks later. Gen. Jackson visited him in his illness, and he was buried in the congressional cemetery with military honors. The tablet on his monument bears this inscription :

Push-ma-ta-ha, a Choctaw chief, lies here. This monument is erected by his brother chiefs, who were associated with him in a delegation from their nation, in the year 1824, to the general assembly of the United States. He died in Washington, Dec. 24, 1824, of the croup, in the 60th year of his age. Push-ma-ta-ha was a warrior of great distinction. He was wise in council, eloquent in an extraordinary degree, and, on all occasions, and under all circumstances, the white-man’s friend. Among his last words were this following : ‘When I am gone let the big guns be fired over me.’ He said that his death would be like the falling of a great tree in the forest when the winds were still.

Citations:

- When this manuscript was originally written, the ancestry of Peter Pitchlynn was unknown. However, since then, research has shown his ancestry and you can read about it here: Pitchlynn Choctaw Family – List of Mixed Bloods.[

]