The tribe that held the Chicago region from about the close of the seventeenth century until 1833 were the Potawatomi. They axe discussed here at some length, as they played an important role throughout the early American period, and we are fortunate in possessing quite detailed accounts of their mode of life. According to a tradition possessed by all three tribes, the Potawatomi, Chippewa, and Ottawa were once one people, and appear in history more or less simultaneously in the territory about the upper end of Lake Huron. The name Potawatomi means “People of the Place of Fire,” as did the Huron name Asistagueroiion, which Champlain used in referring to the western enemies of the Huron. The term “Fire Nation” was at first used rather generally in referring to the Potawatomi, Sauk, Fox, and other tribes whose territories in early times met near Green Bay, Wisconsin. Later, one band of the Potawatomi, those dwelling to the south on the prairie, became known as the Mascoutens, or “Little Prairie-people,” while the other division living in northern Wisconsin became known as the Forest Potawatomi. There seems to have been another Algonkian tribe in the same region who were also known as the Mascoutens, that later merged with the Sauk; hence the unrestricted use of such terms as “Fire People” or “Mascoutens” by early priests and explorers often leaves some doubt as to the exact people referred to. However, as Skinner points out, the term “Mascouten” generally implies a branch of the Potawatomi. Many early accounts mention the Potawatomi, and the impression one receives from these varies with the personal experiences of the writers. As a general rule the French accounts are favorable, and the English accounts are not; for the friendship between the pioneers of France and the Potawatomi was early formed and lasting. In 1666, Father Allouez describes the Potawatomi as “a people whose country is about the lake of the Ill-i-mouek, a great lake than; has not come to our knowledge, adjoining the lake o f the Hurons and that of the Puants [Winnebago at Green Bay] between the east and the south. They are a warlike people, hunters and fishers. Their country is good for Indian corn of which they plant fields, and to which they repair to avoid the famines that are too frequent in these quarters. They are in the highest degree idolaters, attached to ridiculous fables and devoted to polygamy . . . Of all the people that I have associated with in these countries, they are the mast docile and affectionate toward the French. Their wives and daughters are more reserved than those of other nations. They have a kind of civility among them, and make it quite apparent to strangers which is rare among our barbarians.”

In 1718, an official “Memoir on the Indians between Lake Erie and the Mississippi,” gives the following account of the Potawatomi village near Detroit:

“The port of Detroit is south west of the river. The village of the Potawatomies adjoins the fort; they lodge partly under apaquois [an Ojibwa term for reed mats] which are made of mat grass.

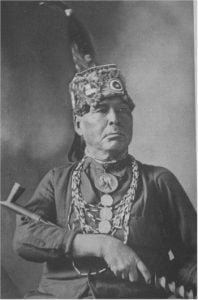

Potawatomi Chief, Rat River, Wisconsin

“The women do all the work. The men belonging to the nation are well clothed, like our domesticated Indians at Montreal. Their entire occupation is hunting and dress. They make use of a great deal of vermilion and in winter wear buffalo robes richly painted, and in summer either red or blue cloth. They play a good deal at La Crosse in summer, twenty or more on a side. Their bat is a sort of a little racket, and the ball with which they play is made of very heavy wood, somewhat larger than the balls used at tennis. They are entirely naked except a breech cloth and moccasins on their feet. Their bodies are completely painted with all sorts of colors. Some, with white clay, trace white lace on their bodies, as if on all the seams of a coat, and at a distance, it would be taken for silver lace. They play very deep and often the bets sometimes amounting to more than eight hundred lives. They set up two poles, and commence the game from the centre; one party propels the ball from one side, and the others from the opposite, and whichever reaches the goal wins. It is a fine recreation well worth seeing. They often play village against village. The Poux [“Lice,” a nickname for the Potawatomi] against the Ottawa, or Huron, and at heavy stakes. Sometimes the French join in the game with them.

“The women cultivate Indian-corn, beans, squashes and melons, which come up very fine. The women and girls dance at night. They adorn themselves considerably; grease their hair, paint their faces with vermilion, put on a white chemise, wear whatever wampum they possess, and are very tidy in their way. They dance to the sound of the drum and si-si-quoi [pronounced shi-shi-gwan] which is a sort of gourd containing some grains of shot. Four or five young men sing and beat time with the drum and rattle, and the women keep time, and do not lose a step. It is very interesting, and lasts almost the entire night.

“The old men dance the medicine [dance]. They resemble a set of demons; and all this takes place during the night. The young men often dance in a circle, and strike posts. It is then they recount their achievements, and dance, at the same time, the war dance; and whenever they act thus they are highly ornamented. It is altogether very curious. They often perform these things for tobacco. When they go hunting, which is every fall, they carry their apaquois with them, to but under at night. Everybody follows men, women and children. They winter in the forest and return in the spring.”

Very different in tone are the various early accounts of the Potawatomi given by the English traders and explorers. John Long (Voyages and Travels in the Years 1768-88) characterizes the Poes (Potawatomi) as “a very wild, savage people, who have an aversion to Englishmen and generally give them as much trouble as possible in passing or repassing the Fort of St. Joseph’s, where some French traders are settled by their permission.” Somewhat similar are the complaints of Sir William Johnston in 1772, in regard to murders and robberies committed by the Potawatomi, instigated by the jealousy of French traders. The Potawatomi were evidently good friends and bad enemies, and seem to have long maintained their individuality and pride even under adverse circumstances. Writing in 1835, in regard to the Potawatomi who had been removed to Council Bluffs, Iowa, Father De Smet says, “We arrived among the Potawatomi on the afternoon of the 31st of May. Nearly 2,000 savages in their finest rigs and carefully painted in all sorts of patterns, were awaiting the boat at the landing. I had not seen so imposing a sight nor such fine-looking Indians in America: the Iowas, the Sauk, and the Otoe are beggars compared to these.” Simon Kahquados, a recent chief of the Potawatomi in Wisconsin, whose portrait is given here, illustrates Father De Smet’s description of the imposing appearance of the Potawatomi.

Recent studies of the Prairie Potawatomi have been made, and more is known of their daily and ceremonial life than is the case with the Illinois or Miami. The Potawatomi have for along time been divided into two divisions, the Forest and Prairie groups. The former group appears to have kept most of the old culture traits characteristic of the Algonkian peoples in general; while the Prairie bands have been influenced first by the Miami and Illinois tribes, and later by the Sauk and Fox, so that their customs which prevailed some fifty years ago seem somewhat mixed. There were about ten bands of the Prairie Potawatomi, the largest of which called themselves “Muskodens,” and formerly dwelt about the southern end of Lake Michigan with their main town at the site of modern Chicago. Prairie Potawatomi society was composed of some twenty-three clans, which reckoned descent in the father’s line. They were named after natural phenomena such as the raven, bear, buffalo, man, etc., and these were grouped according to type of name, for example, the sea and fish clans would belong to the water division or phratry. In addition to these groupings there were two large divisions of society characterized by the use of black or white paint, the oldest child always joining the former division, the second child the other, and so on in succession. A similar division of all the tribe between the upper and lower worlds, according to whether the clan totem was a bird or a mammal, also existed.

Each clan had a sacred bundle containing various objects believed to be sacred. It was the possession of such bundles that gave power and success to the clans in their activities according to the belief of the Indians. Many of the bundles were supposedly given the clans by the great culture hero Wi’saka, but others were acquired or made as the result of dreams, or visions of the people who originated the clan. Thus each bundle came to have a special legend attached to it, accounting for its origin.

Above, drum of the Waubano Society, with design symbolizing the dawn. Below two ceremonial pipes.

The chieftainship of the Prairie Potawatomi was usually hereditary in the fish clan, and the chief was largely a civil and military authority. He appointed each year a ceremonial chief who conducted all the ceremonies and activities of the people. Should a man commit murder, the tribal chief would send for the keeper of the tribal peace-pipe, and a council would be held to discuss the case. If the chief thought the man guilty, he would smoke the pipe, and the murderer would be executed. If the man appeared not to be guilty, the pipe bearer with flint and steel would attempt to light his pipe; if he succeeded in four strokes of the steel, the man went free; but if he failed, the man was executed. It was possible for an influential man to escape the consequences of three murders; but if he should kill four people, nothing could save him.

Special names in honor of their exploits were given to warriors who were brave in battle, and war honors were awarded to the first four men who touched a dead foe, in order of precedence. This was a much more noteworthy feat in the eyes of the Potawatomi than merely killing an enemy. A single tuft of hair from the crown of the head was taken as a scalp; prisoners were often tortured and scalped by the boys and young men. Before war parties the aid of the clan bundles was invoked, and special war bundles were carried by the leaders on campaigns, in front of them on the out trip and behind them on the return, so that the bundle would always be between them and the enemy.

Young children were given names at a ceremony for the clan bundles, and these names usually referred to the name of their clan. In former times when children reached the age of about ten years, the parents would urge them to fast all day and seek a vision. By the time children were fifteen or sixteen years of age, they were made to go from four to eight days without eating or drinking. All this was to enable the children to have a vision which would give them a guardian spirit through life, and would bring them success. Only when he had obtained such a dream was a boy considered to be a man.

Marriages were usually arranged between the parents of a boy and girl, but the boy’s and girl’s consent was usually obtained. If all parties agreed, then the boy came to his bride’s lodge that night, and the marriage was concluded. Sometimes a youth would pick out the girl he wanted for himself and tell her his desire. If she was agreeable, she had her family invite all his relatives to a feast. Then, well mounted, the groom rode to the bride’s house and dismounted, going into the wigwam where the girl sat beside the rawhide trunks that held all her possessions. Standing there, the boy took off all his clothes and presented them to her; and she, opening her trunks, gave him an entire new outfit of clothing which he donned immediately. Then the feast began, the two families exchanging food. At the close of the feast an old man lectured the young couple on their mutual duties, and other relatives of both of them followed in turn. The horse was brought out, and the girl rode over to the boy’s lodge: here his relatives dressed her in new clothes, and she returned, bringing all the groom’s possessions. Thus the marriage was concluded.

The houses of the Potawatomi were similar to those of their neighbors; the round birch bark and mat house was used in winter, and the larger, rectangular, mat-covered house in summer. Occasionally buffalo hide tipis were used. When a new lodge was made in the autumn, a feast of dog meat, elaborately prepared, was eaten, and offerings of tobacco and cedar smoke were made before the house could be occupied. In such rites the chief’s wife was always first, and the others followed. A similar ceremony occurred in the spring when they moved into the square mat-houses.

The leaders of the annual buffalo hunt were chosen from among the principal men of the buffalo clan, and usually the keeper of the clan bundle was chosen. A feast was then held, and imitative ceremonies supposed to attract the buffalo were held.

At the close of the feast, representatives of the two tribal divisions (moieties) held an eating race; the winners in consuming the hot food were appointed to carry the sacred buffalo clan bundle on the hunt. Sixteen braves were appointed by the leader as guards or police, and these carried elkhorn-handled whips with which they enforced the rules of the hunt. As they traveled west toward the buffalo ranges, no hunting was allowed for fear it might frighten the herds.

When the buffalo were sighted, the hunters were divided in two groups to surround the herd if possible, and the hunt was carried on under the control of the sixteen police. When the first hunt terminated, each person brought a piece of meat to the leader as an offering, and a ceremonial feast was held. After this the hunt was resumed, but all were now allowed to hunt separately and as they pleased. When the hunt was over a feast was held, dried meat, robes, and tallow were packed, and the people started for home. On the return trip the four men beaten in the eating contest carried the buffalo clan bundle. At night the hunters fired the prairie, so that those remaining at home might see the smoke and prepare the camp for their reception. When they reached camp, all repaired to their own houses; the next day a feast was held by the buffalo clan to name all children born while the hunt was on. After this ceremony was over, all the other clans had naming ceremonies and feasts. Then followed a time of games and feasting.

The Potawatomi likewise sent out quite large parties to secure deer, and black bears were hunted in winter when they were sleeping in caves. Beaver, otter, mink, and muskrat were trapped and snared for fur and for food. Gill nets of bark or fibre twine were made and set in lakes and streams; in the winter time fish were speared through the ice, or were caught in seines. In the spring, quantities of ducks and geese were killed and preserved in brine. In addition to all these products of the chase, they cultivated maize, squash, beans, and tobacco, while the forests and lakes furnished quantities of berries and wild rice. As the account of Allouez indicates, famines occurred when one or more staples failed them, but ordinarily the people of the Great Lakes must have had a large The art of the Potawatomi as manifested in porcupine quill and bead work seems more characteristic of the Central Algonkians than the Plain’s tribes. This design work appears most commonly on their medicine bags, clothing, and mats, and is characterized by either flamboyant scroll-work or by isolated graceful designs. Diamond-shaped central figures, with leaf or scroll corner designs, rectangular diamond shapes with different colors in them, and spider-web designs are all typical Potawatomi motifs according to Mr. M. G. Chandler, who is well acquainted with their art and varied foo

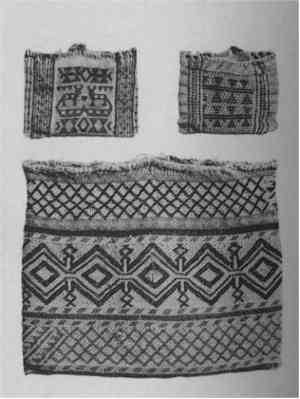

Upper left, for ceremonial articles,

decorated with horned water-panther design. Upper right for ceremonial

articles. The one below was used for personal possessions.

d supply.

The Potawatomi of the lakes had both birchbark canoes and dugouts which are typical of the Lake tribes; but the Prairie Potawatomi while on the plains used the bull-boat, a raw buffalo hide stretched over a wooden frame, to transport their goods across rivers. Similarly, after the introduction of the horse, they used the travois, two poles dragged on each side of a horse, with their possessions lashed on behind. The war club, the lance, the bow and arrow, and the knife constituted the weapons of the Potawatomi. Like the travois and the bull-boat, the Prairie Potawatomi made use of a. round shield of buffalo hide. These three things are more typical of the Plain’s tribes than of the Eastern Woodland peoples to whom in most other characteristics the Potawatomi belonged.

The clothing of the Potawatomi which is still obtainable largely represents colonial styles of the early settlers, re-adapted by the Indians.

The decorative designs on this clothing are largely native, whether in bead or ribbon appliqué work, but the material, and in some cases the cut, is derived from the whites. The collection of Potawatomi clothing and decorative bead and quill work gathered for the Museum by Mr. Chandler, and now on exhibition, clearly demonstrates the above points.

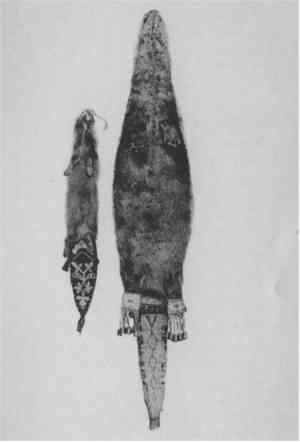

The one on the left made of mink skin with bead decorations. The other of

otter skin with porcupine quill decorations.

The religion of the Potawatomi, like that of most of the Central Algonkian people, is hard to reduce to a formula, largely because it does not seem to have been formally conceptualized in the minds of the Indians. Schoolcraft states that the Potawatomi believed in a good spirit and a bad spirit who governed the world between them, but this is a reflection of the Christian doctrine. They did, however, conceive of a “Great Spirit” which originally may have been the sun; and besides this vaguely personified deity, their pantheon contained the archaic deities of fire, sun, and the sea, as well as gods of the four directions. The evil power in the water was the great horned water-panther, who was at constant war with the Thunderbirds. The worship of the manitou, or power believed to be in other natural objects such as plants or animals, was also a vital part of their religious belief. They believed that the human body had but one soul or spirit, and that this spirit eventually followed a trail over the Milky Way into the western heavens to a land ruled over by Tcibia’bos, the brother of Wisaka, the great culture hero. The power of the various manitou or spirits was often visualized by the sacred clan bundles, and around these most of their ceremonials radiated. At such feasts specially reared dogs were eaten, and no ceremonial was complete without dog meat. Dogs used for this purpose were carefully raised, kept from the polluting association of other dogs, and only killed after many formalities had been observed. Besides the clan bundle ceremonials there are those of the medicine lodge which may be joined by men and women. The purposes of the society are to prolong life, cure sickness, and in their keeping are various sacred myths of the Potawatomi. In the medicine lodge ceremonies decorated animal skins are carried. The ritual and initiation ceremonies are complex and known only to the initiated. There are various other societies, such as the Waubano society or cult, composed of those men who in their visions saw phenomena connected with the dawn. The drum of a member of the Waubano society which depicts his vision is shown in the Medicine Bag. Other cults existed based on other dream experiences, such as the Dream or Religion dance, of rather late origin, and in addition to these are the Warrior’s, Begging, and purely social dances.

The Potawatomi claim to have received from the Comanche the series of ceremonies called the Peyote cult. These ceremonies center around a small cactus which grows in Mexico and the southwestern United States, that produces a sort of spiritual exaltation when eaten. The spread of the Peyote cult in historic times has been remarkable, and to-day it is one of the strongest cults existing among the Indians of the United States and Mexico.

For three nights after a death the clan members of the deceased sing, pray, and go through ceremonies to propitiate and scare away the ghost. A coffin is then made from a hollow tree, members of another clan dig the grave, and the body is buried in the cemetery of the clan to which the person formerly belonged. It is interesting to note that dead members of the man, or human clan, were interred sitting up against a back best, with a framework of logs around them. With the dead are placed a few weapons or utensils, and formerly a favorite horse was sacrificed at the man’s grave to serve his master in the journey to the other world. Various mounds have been found in the vicinity of Potawatomi burials, but there seems to be no correlation between any type of mound and the burials of the tribe.

Scattered as the Potawatomi are at present, many of their old ceremonies are still carried on. It is still possible in northern Wisconsin to find groups whose religious life is largely colored by the beliefs of their ancestors.