Forty years before Spain was able to establish a permanent colony in North America, North Africans attempted to obtain permanent resident status in the Land of the Free. This is a documented fact, not speculation or an interpretation of available circumstantial evidence. What is not known is whether they were accepted as citizens of a particular indigenous province, started their own community or were killed by the locals. Because of the propensity of Native Americans to be initially hospitable to guests, the probability is high that at least some of these newcomers survived and added their DNA to the regional gene pool.

The Southeast’s coasts were particularly dangerous for ships and fishing vessels before Europeans became aware that hurricanes were common in the late summer and early fall. The Spanish ships generally followed the Gulf Stream when sailing back to Europe and therefore were fairly close to land, when encountering trouble. However, unlike most coasts of Europe, landfall was not particularly dangerous because there were no rock boulders that could crush ships and humans.

There is no accurate measure of the number of shipwrecks along the South Atlantic Coast and the Gulf of Mexico, but the number must be in the hundreds or even over a thousand. Also not known is how many shipwrecked sailors and passengers survived in North America during the 1500’s and 1600’s, or how many Sephardic Jews, Muslim Moors and European Protestants, escaping the Spanish Inquisition, landed on the shores of the present day Southeastern United States. Surviving archives, however, do furnish credible evidence of these peoples settling in the interior of the Southeast, while officially England was only colonizing the coastal regions.

San Miguel de Gualdape Colony (1526-1527)

In 1526, Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón, a wealthy Spanish sugar planter from Hispaniola, personally financed a colonial expedition that contained over 600 colonists. 1 Historians currently believe that the colony was established on one of the islands at the mouth of the Altamaha River in Georgia. Ayllón either was not a competent logistics planner or he expected to steal what food he needed from neighboring indigenous villages, as was the practice farther south. However, the indigenous peoples along the coast were only part time agriculturalists. Much of the flat terrain was unsuitable for agriculture, especially on the islands.

While the village was under construction, the 80 Moorish prisoners-of-war, who were essentially slaves, became increasingly irritable and finally rebelled. Apparently with the connivance of neighbor Indians the Moors went AWOL. They were never seen or heard from again. Unlike in the Arawak culture, it was the custom of Muskogean provinces to be inclusive. Great Suns often ruled over several ethnic groups. Bands of friendly strangers would be assigned to unoccupied lands and incorporated into the province. Therefore, it is quite likely these Moors settled somewhere within the interior of Georgia and intermarried with the locals. Muskogeans originally had no concept of skin color-based racism. 2

A lethal form of dysentery, with symptoms like cholera, swept through the colony, eventually killing many of the colonists, including Ayllón. Meanwhile, the survivors suffered from starvation and scurvy. A total of about 150 colonists made it back to Hispaniola in the late spring of 1527.

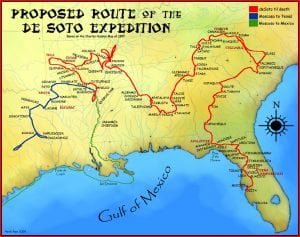

Hernando de Soto Expedition (1539 – 1543)

At first morale was high in this expedition, but as more and more soldiers began to be snipped off in guerilla attacks and no wealthy city like the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan was encountered, desertions occurred. Most of the deserters were Moorish or Sub-Saharan servants. The first desertion given extensive discussion by the authors of the De Soto Chronicles occurred in the vicinity of Saluda, NC, which was then called Suale. 3 The location was on the Blue Ridge escarpment. A high ranking female leader from the town of Kofitachiki in southeastern South Carolina was being held hostage. She pretended to need to answer the call of nature then escaped with one of the African servants.

While leaving Kvse (Coça ~ Coosa) in northwest Georgia, de Soto lost at least two or three more men. Robles broke his leg when he fell off his horse, and could not march. Another was a hidalgo (noble) name of Manzano of Salamanca, who disappeared several days before the army departed. 4 The other was a Moorish servant, named Feryado, who intentionally slipped away from the Spaniards as they marched to the west. It is quite likely that de Soto lost several other common soldiers in the highlands because the Spaniards were enthralled with the terrain. Other desertions in this region are not mentioned by the chroniclers until further along on the route.

Consult Further:

- Hernando Cortez

- Hernando de Soto

- Hernando de Soto Expedition to Georgia

- Where was Hernando de Soto’s Guaxale?

Fort Caroline (1564-1565)

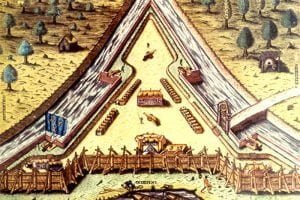

Fort Caroline dispatched at least six small expeditions to explore the interior of the Southeast in order to develop trade ties. 5 Most of the expeditions were targeted toward the Appalachian Mountains. Upon the arrival of 600 new colonists, René de Laundonnière planned to establish the capital of New France at the head of freight canoe navigation on the Oconee River. This is approximately the location of the University of Georgia today. The proposed town site was about 15 miles from the Georgia gold belt.

Spanish forces attacked Fort Caroline on the night of September 20, 1565. 6 Most of the approximately 200 men in the garrison were killed in battle or executed. A handful escaped with the fort’s commander, René de Laundonnière. Somewhere around 6-10 men were either away from the fort on a trade mission to the Appalachian Mountains or else were able to swim away from the fort, when it was attacked. Two of the survivors lived with nearby Natives until picked up by a French retaliatory raid in 1568. The best known of traders who were away was Pierre Gambié. He eventually married the daughter of a king then became a king himself. A story survives that he was eventually assassinated, but other evidence suggests that he created this story to conceal his identity from the Spanish.

Consult Further:

- Where was Fort Caroline?

- Geography Around the Coastal Region of Fort Caroline

- The Non-Search for Fort Caroline and a Great Lake

- Don Pedro Menéndez de Avilés Arrives at Fort Caroline

- Jean Ribault Arrives at Fort Caroline

- The Third Voyage to Fort Caroline

French Protestant refugees and privateers (1565-1620)

According to documents that will be discussed in subsequent sections, several of the survivors of Fort Caroline established permanent residence in the Georgia Mountains at the invitations of the kings of Apalache and Ustanali. At the time, the majority of French mariners were Protestant. Many turned to privateering as a means of covertly combating the Catholic League and Spain. Through the privateers operating off of the Florida Straits, the Fort Caroline survivors got word back to France of a sanctuary for Protestants in the Appalachian Mountains. They were subjects of the Native American king of Apalache, but persuaded him to become a Christian.

Juan Pardo Expeditions (1567-1568)

To confirm the King of Spain’s claim to the Southern Piedmont and Appalachian Mountains, Pardo established a chain of small timber palisade forts in 1567 and the fall of 1568. 7 Pardo never mentioned Apalache in his report. The provinces that Pardo visited in the mountains were vassals of the King of Apalache. He obviously did not have permission of the High King of Apalache to build these forts. Just as Pardo arrived back at his home base in Santa Elena during early March, he learned that all of his forts had been massacred; at least that is the official story. Supposedly only one soldier survived.

In the following month the three Spanish forts at the mouth of the Altamaha River were wiped out by an army led by Dominique de Gourgues. Were all the soldiers in these garrisons killed or did many go AWOL in order to pan for gold and marry Native women? We don’t know at this time.

Dominique de Gourgues Expedition (1568)

De Gourges’ two ship fleet temporarily anchored off the south coast of Cuba in early November of 1568. 8 De Gourges is totally silent about where he was and what he did until he rendezvoused in mid-April at a pre-designated anchorage on the Medway River in Georgia, the location of the village of Tacatouru. The location was near present day Midway, GA, 24 miles south of present day Savannah, GA. All of the forts built by Pardo were destroyed during this period of De Gourge’s silence. The systematic destruction of Spanish power north of St. Augustine suggests that some Europeans were operating as “advisors” to Native provinces in the interior. De Gourges’ report to the king leaves many unanswered questions.

Jewish pirates of the Caribbean (1580 – 1700)

In 1580 Spain and Portugal became one country. There had officially been no Jews in Portugal since 1497, when all were forcibly baptized. However, the King of Portugal did not harass Jewish families, who continued to keep a low profile with their religious practices, because he needed their mercantile expertise. 9 The crypto-Jews in Portugal knew, however, that the Inquisition would soon follow annexation. They established trade networks in Brazil, Colombia and the Caribbean Basin – then migrated to the Americas by the hundreds, perhaps thousands.

There was a large concentration of Portuguese Crypto-Jews in Puerto Rico, Barbados, Jamaica and the Bahamas. 10 This probably explains why both the ships of the Roanoke Island Colony and the later Jamestown Colony were able to anchor in southern Puerto Rican harbors for many days in order to replenish supplies and rest. At the time of the Roanoke Colony, Spain and England were at war.

Those Portuguese Jews living in the Bahamas and Jamaica were in ideal situations to trade with the embryonic colonies on the mainland of North America. It is suspected that many of the handfuls of Spaniards, who established rural haciendas in Florida, were really cryptic Jews seeking isolation from the Inquisition. However, many more were lured by the quicker profits and hatred of Spain to become pirates.

The Jewish pirates of the Caribbean attacked and plundered the Spanish fleet while forming alliances with England and the Netherlands to ensure the safety of Jews living in hiding in the New World. 11 They waited off the Florida and Georgia coasts to spring on treasure laden galleons that were plodding up the Gulf Stream. They were probably the “pirates” who raided the Spanish coastal missions in Georgia.

Because they maintained illegal operations on a regional scale just off the coast of the Southeast, the Jewish pirates were in an ideal situation to operate gold and silver mines in the Appalachians without the king’s approval. They also could have easily transported religious refugees to the coast and arranged for safe passage through the Native provinces between the coasts and the mountains.

Sir Francis Drake at the First Roanoke Colony (1586)

After burning St. Augustine, the fleet of Sir Francis Drake sailed north to check on the health of the Roanoke Colony. 12 In his ships he carried approximately 386 African slaves and former Turkish prisoners of war captured at St. Augustine. Some scholars have interpreted his archives to indicate that Drake set free on a South Atlantic beach some or all of the men that he carried away from St. Augustine, because he did not have enough food reserves to feed them and resupply the Roanoke Colony. If the story is true, these freed captives may have been able to survive within the interior of the Southeast. However, there is other evidence that suggests that no freed captives were released at Roanoke Island. Some may have been released elsewhere, but Drakes memoirs are vague on this subject.

Second Roanoke Colony

In 1587, 112 men, women and a child were left stranded on Roanoke Island, NC with no scouts, no experienced hunters or fishermen, no hope of feeding themselves on the infertile soil and surrounded by hostile Native. 13 It would be three years before Governor John White would be able to return briefly to check on their well-being. They were gone. They had disassembled their houses before leaving. There were no skeletons or signs of violence. It is one of America’s favorite historical legends.

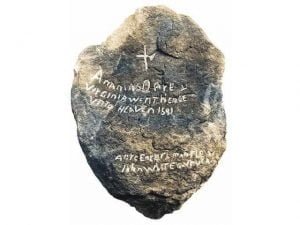

In September of 1937, a California produce dealer, named L. E. Hammond, was vacationing on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. 14 While deep in the woods near Edenton, NC, searching for hickory nuts, he discovered a moss-covered quartzite slab with strangely spelled English on it. Thinking it was a pirate treasure map, he dropped it off at Emory University on the way back to California. Emory gave the stone to a professor at Brenau College in Gainesville, GA. The professor figured out that the stone was a grave marker for Ananias and Virginia Dare of the Lost Roanoke Colony.

National publicity caused farmers in several locations along a diagonal line in Carolinas and Georgia to produce more stones, written in Elizabethan English. Then a farmer in the Nacoochee Valley produced eight slabs inscribed with Elizabethan English that he said he had found earlier in a cave. He didn’t know what they were until hearing the publicity about the other stones. One of these slabs was the grave marker of Eleanor Dare, mother of Virginia. According to the inscription, she had married an Indian chief, bore him a child, and then died in 1599. The marker was signed by another survivor, Griffin Jones.

In 1937, Pulitzer Prize winning playwright, Paul Green, created the outdoor drama, “The Lost Colony” for performances on Roanoke Island, NC. By 1940, Brenau College created its own Roanoke Colony drama that continued the story to the new lives that survivors found in the Georgia Mountains. It competed directly with the original play in North Carolina.

Some obviously faked stones and markings on boulders were publicized during 1938 and 1939. 15 North Carolina officials pressured the Saturday Evening Post to publish a second article on the Eleanor Dare Stones which labeled them as hoaxes. In the minds of mid-20th century scholars, the most bogus part of the interpretation promoted in Georgia was that the colonists would head straight to the Nacoochee Valley in the Georgia Mountains. Any sensible colonist would have north headed to the mouth of the Hudson River, not to remote mountains in backward Dixie!

Scott Wolter, a forensic geologist, who hosts the History Channel’s America Unearthed, tested both the Virginia Dare and Eleanor Dare grave markers. 16 Using the most advanced technology available, he found the writing both to date from the late 1500’s. English colonists probably did settle in the Nacoochee Valley. In later sections of this series, the reader will find out why.

Spanish Inquisition in Cartagena, Colombia

Many of the Sephardic Jews, who migrated from Spain to Portugal, then from Portugal to the New World, ended up in Cartagena, Colombia. 17 The local Spanish officials were tolerant of them as long as they paid their propinas (bribes.) The wealthiest Sephardic families in Cartagena were involved with gold/silver mining or the African slave trade. Cartagena and Vera Cruz, Mexico were the only two ports in which African slaves could be traded. Other families were developing regional trade networks among the Spanish colonies that were independent of Spain.

In 1610 the Inquisition arrived in Cartagena. Cartagena, Mexico City and Lima, Peru were the bases of the Inquisition in the Americas. Families, who had been openly practicing Judaism, had to leave town fast. It is believed that most initially resettled in Jamaica and the Bahamas, where the Jewish pirates were based. Since by 1610, Spanish forts and colonies north of St. Catherines Island, GA had been abandoned, it would have been quite simple for the pirates to ferry the Sephardic families, or at adventurous young Sephardic men, to the Savannah River, where they could paddle directly up to the Appalachian Mountains. At the head of the river was the powerful province of Ustanoli.

There was a second period of persecution in Cartagena, begun by the Inquisition in 1635. This ethnic-cleansing campaign was more invasive in that it went after the Jewish families that publicly attended mass, but privately observed Jewish traditions. It began with the arrest and torture and burning of 10 of Cartagena’s most prominent citizens. The remaining families, who still practiced Jewish traditions or feared that they would be framed quickly, disappeared from Cartagena.

Again, it is presumed that they headed north to the safer environs of the Bahamas and Jamaica. British settlers began arriving in the Bahamas is 1648. Jamaica was claimed by the British in 1655. It is believed that Sephardic Jewish pirates openly assisted England in their military operations against the Spanish during this period.

English colonists from Virginia

Several, published, 17th century books reported that a party of English colonists in 1621 had originally planned to settle in Virginia, but arrived on the coast just as the massacres of the Powhatan Rebellion were occurring. 18 The colonists headed south, but were persuaded by either the ship’s captain or someone on board the ship, to seek refuge in the Appalachian Mountains. The king of Apalache let them stay in the Nacoochee Valley. The colonists found the place so agreeable that they asked to settle there permanently. As will be discussed in Part Six, several French Huguenot eyewitnesses encountered the descendants of the English colonists in the late 1600’s and worshiped with them in a Protestant chapel!

Citations:

- Weber, David, The Spanish Frontier in North America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994; p. 37.[

]

- Saunt, Claudio, A New Order of Things: Property, Power, and the Transformation of the Creek Indians, 1733-1816, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.[

]

- Knight, Clayton, et al, The De Soto Chronicles, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994, Chapter XV.[

]

- Knight, Clayton, et al, The De Soto Chronicles, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994, Chapter XV.[

]

- Bennett, Charles C., Three Voyages, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001.[

]

- Bennett, Charles C., Three Voyages, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001.[

]

- Bandera, Juan de la, Relacion de la Florida, 1569; pp. 268-269 of the Ketchum translation.[

]

- Hakluyt, Richard, The Voyages of René de Laundonnière (1582) The Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and Discoueries of the English Nation, vol. IX.[

]

- Duncan-Hart, Ronald, World Politics, Illegal Jews and the Inquisition of Cartagena, Oklahoma City: Institute for Tolerance Studies, 2006.[

]

- Kritzier, Edward, Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean, New York: Anchor Books, 2009.[

]

- Kritzier, Edward, Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean, New York: Anchor Books, 2009.[

]

- Johnson, Betty Drees (1961). “A Survey of Sir Francis Drake’s Raid on St. Augustine,” Florida, 1586. University of Stetson.[

]

- Milton, Giles, Big Chief Elizabeth: The Adventures and Fate of the First English Colonists in America, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000.[

]

- La Vere, David, The Lost Rocks: The Dare Stones and the Unsolved Mystery of Sir Walter Raleigh’s Lost Colony, Wilmington, DE: Burnt Mill Press, 2011.[

]

- La Vere, David, The Lost Rocks: The Dare Stones and the Unsolved Mystery of Sir Walter Raleigh’s Lost Colony, Wilmington, DE: Burnt Mill Press, 2011.[

]

- American Unearthed (History Channel H2) Season 1, Episode 7, “The Lost Roanoke Colony.”[

]

- Duncan-Hart, Ronald, World Politics, Illegal Jews and the Inquisition of Cartagena, Oklahoma City: Institute for Tolerance Studies, 2006.[

]

- De Rochefort, Charles, Histoire naturelle et moraledes îles Antilles de l’Amérique, Rotterdam: Armout Leers, 1665.[

]