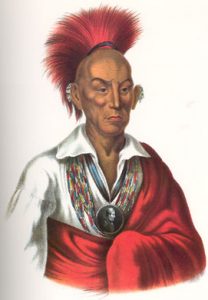

We have now to record the events of a war “which brought one of the noblest of Indians to the notice and admiration of the people of the United States. Black Hawk was an able and patriotic chief. With the intelligence and power to plan a great project, and to execute it, he united the lofty spirit which secures the respect and confidence of a people. He was born about the year 1767, on Rock river, Illinois. At the age of fifteen he took a scalp from the enemy, and was in consequence promoted by his tribe to the rank of a brave.

Engaging soon afterwards in an expedition against the Osages, he fought several battles, highly distinguished himself, and brought back a number of trophies. His reputation being thus established, he frequently led war parties against the enemies of his tribe, and was, in almost every case, successful. The influence and experience he thus acquired were fitting him for a contest in which, though unfortunate, he was to acquire a lasting fame.

The treaty concluded in 1804, by Governor Harrison, with the Sacs and Foxes, by which these tribes ceded their lands east of the Mississippi, was agreed to by a few chiefs, without the knowledge or consent of the nation. Although this gave rise to much dissatisfaction among the Indians, no outbreak occurred, until the United States government erected Fort Madison upon the Mississippi. An attempt was then made to cut off the garrison, and from that time, the whites looked upon the Indians as enemies, and so treated them whenever opportunity offered.

Previous to this, Illinois had been admitted into the Union as a state; and, attracted by the fertile soil of the country; emigrants knocked into it and soon surrounded the land occupied by the Sacs and Foxes. As they thought the proximity of the Indians dangerous, the emigrants began to commit outrages intended to hasten their departure. In 1827, when the tribes were absent from home on a hunting excursion, some of the whites set fire to their village, by which forty houses were consumed. With admirable forbearance, the Indians paid little attention to this disgraceful conduct, but quietly rebuilt their dwellings, raised the fences which had been broken down, and saved as much of their corn as was possible.

The American government now determined to sell the land occupied by these tribes, and they were accordingly advised to remove. Keokuk, the chief, with a majority of the nation, determined to do so; but Black Hawk, and the party which he had gained over to himself, resolved to remain at all hazards.

Meanwhile the whites committed greater acts of violence upon the Indians than before. The latter at last took up arms, and a war would certainly have taken place, had not General Gaines, commander of the western division of the army, hastened to the scene of action. This able and prudent officer immediately convened a council of the principal chiefs, in which it was agreed that the Indians should instantly remove. They accordingly crossed the river and settled on its western bank. Not-with-standing this measure, a majority of the Indians were on peaceful terms with the United States. But Black Hawk and his band determined on returning to Illinois, alleging that they had been invited by the Pottawatamies, residing on Rock River, to spend the summer with them and plant corn on their lands. They re-crossed the river, and marched toward the above named Indians, but without attempting to harm anyone upon the road. The traveler passed by them without receiving any injury and the inmates of the lowly hut experienced no outrage. There is little doubt but this amicable disposition would have continued had not the whites been the first to shed blood. Five or six Indians, in advance of the main party, were captured, and excepting one who escaped, put to death by a battalion of mounted militia. That one brought the news to Black Hawk, who immediately determined on revenge. He accordingly planned an ambuscade into which the militia was enticed, fired upon, and fourteen of their number killed. The remainder fled in disorder.

As war had now begun, the Indians seemed resolved to do all the mischief in their power. Accordingly they divided into small parties, proceeded in different directions, and fell upon the settlements which were at that time thinly scattered over the greater part of Illinois. By this means they committed such outrages that the whole state was in the greatest excitement. Governor Reynolds ordered out two thousand additional militia, who, on the 10th of June, assembled at Hennepin, on the Illinois River, and were soon engaged in pursuit of the Indians.

On the 20th of May, 1832, a party attacked a small settlement on Indian creek, killed fifteen persons, and took considerable plunder. On the 14th of June, five persons were killed near Galena. General Dodge being in the neighborhood, immediately marched with his mounted men in pursuit of the enemy. After advancing about three miles, he discovered twelve Indians, whom he supposed to be part of those who committed the murders. He commenced an active pursuit and drove the Indians into a swamp. The mounted men rushed in and soon met them. No resistance was made; every Indian was killed, their scalps taken off and borne away in triumph.

Meanwhile, General Atkinson was pursuing the main party, under Black Hawk, who was encamped near the Four Lakes. Instead of crossing the country to retreat beyond the Mississippi as was expected, he descended the Wisconsin, to escape in that direction, by which means General Dodge came upon his track and commenced a vigorous pursuit. On the 21st of July, the general, with about two hundred men, besides Indians, overtook him on the Wisconsin, forty miles from Fort Winnebago. The Indians were in the act of crossing the river. After a short engagement they retreated and it being dark the whites could not pursue them, without disadvantage to themselves. In this encounter Black Hawk‘s party lost, as is supposed, about forty men.

The Indians were now in a truly deplorable condition; several of them were greatly emaciated for want of food, and some even starved to death. In the pursuit previous to the battle, the soldiers found several lying dead on the road. Yet so far from being subdued they resolved to continue hostilities as long as they were able.

Meanwhile an army under General Scott, destined for the subjugation of Black Hawk, and the removal of all the northwestern Indians to lands beyond the Mississippi, had been attacked by an enemy far more fatal than the Indians. With about one thousand regular troops, Scott sailed from Buffalo in a fleet of steamboats across Lake Erie for Chicago. This was early in July. On the 8th of that month, the Asiatic cholera appeared on board the vessel in which were General Scott, his staff, and two hundred and twenty soldiers. In six days fifty-two men died, and soon after eighty were put on shore sick at Chicago.

In the summer Scott left Chicago with but about four hundred effective men, and hurrying on to the Mississippi, joined General Atkinson at Prairie du Chien, immediately after the battle, near the Badare River, which resulted in the defeat of Black Hawk.

Previous to this affair, a captured squaw had informed the whites that Black Hawk intended to proceed to the west side of the Mississippi, above Prairie du Chien the horsemen striking across the country, whilst the others proceeded by the Wisconsin. A number of the latter were made prisoners on the road.

Meanwhile, several circumstances transpired to prevent the escape of the main body under Black Hawk. The first was his falling in with the Warrior steamboat, (August 1st,) when in the act of crossing the Mississippi. Wishing to escape, he displayed two white flags, and about one hundred and fifty of his men come to the river without arms and made signs of submission. The commander of the boat ordered his men to fire, which they did, and the fire was returned. The engagement lasted an hour, when the wood of the steamboat failing, it proceeded to the Prairie. The Indians lost twenty-three killed, and a number wounded; the whites had one wounded.

Next day, after a toilsome and dangerous march, General Atkinson overtook Black Hawk, and a furious contest ensued. In order to prevent the escape of the Indians, Generals Posey and Alexander, with the right wing, marched down this river, and stationed themselves near the encampment. The rough nature of the ground afforded every facility for the Indians to make a strong defense, and Black Hawk took advantage of it. The battle lasted three hours, at the end of which time; the Indians were totally routed and dispersed, killed or captured. Black Hawk succeeded in escaping. The loss of the American troops in killed and wounded was twenty-seven men. The loss of the enemy could not be ascertained; but it was supposed that their killed amounted to one hundred and fifty persons, of whom about fifty were women and children.

This battle finished the war, for, although Black Hawk escaped, his warriors either deserted him or were killed by the Sioux Indians, then at war with the Sacs. Finally when hope had fled, Black Hawk surrendered himself to the agent at Prairie du Chien. In his speech upon this occasion, he regretted his being obliged to close the war so soon, without having given the whites much more trouble. He asserted that he had done nothing of which he had any reason to be ashamed, but that an Indian who was as bad as the whites would not be allowed to live in his community. His concluding words are remarkable for pathos and dignified sorrow.

“Farewell, my nation! Black Hawk tried to save you, and revenge your wrongs. He drank the blood of some of the whites. He has been taken prisoner, and his flames are stopped. He can do no more. He is near his end. His sun is setting, and he will rise no more. Farewell to Black Hawk!”

Immediately after the battle which decided the struggle, General Scott joined General Atkinson, but their operations were hindered for some weeks by the dreadful pestilence which had fearfully thinned the ranks of the army. Late in September, negotiations were commenced with the Sacs and Foxes, and so skillfully were they conducted by General Scott, that a region of five million of acres of land was obtained from the Indians on terms satisfactory to both parties. See the treaty of September 21, 1832.

When peace had been secured, Black Hawk was taken to Washington, where he had an interview with President Jackson. He was then conducted through the principal Atlantic cities, and every where received with the most marked attention and hospitality. He was then set at liberty and returned to his own nation, professing friendship to the whites. Black Hawk died on the 3d of October, 1838, at his village on the Des Moines River.