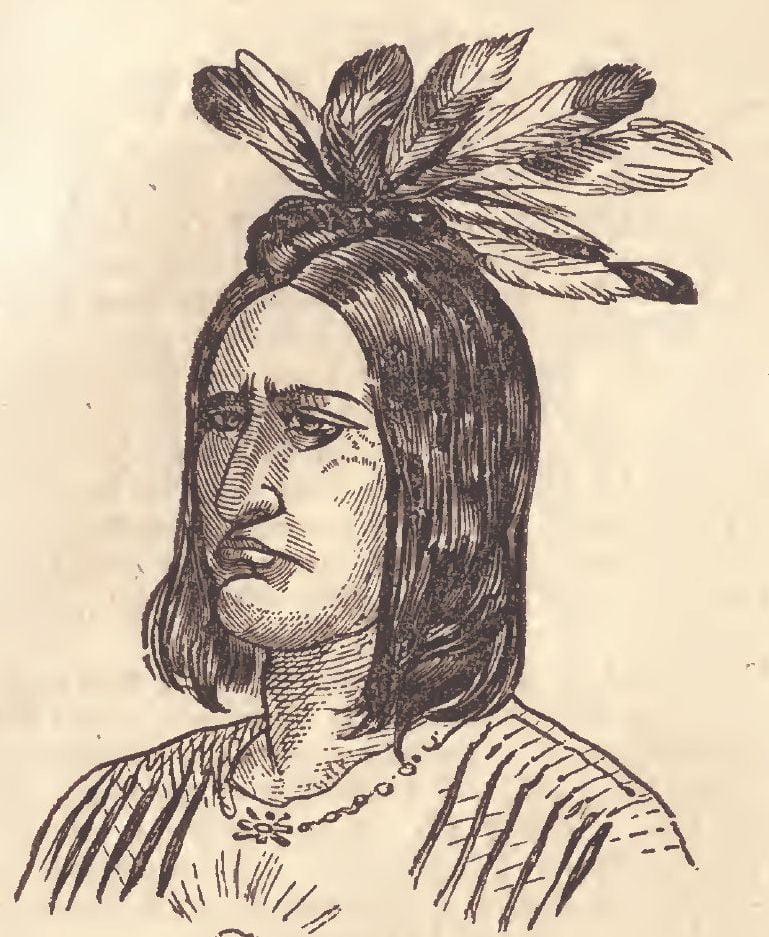

The second Seminole war against the Indians and runaway Blacks in Florida commenced in 1835. A treaty had been concluded with the Seminole warriors, by which they agreed to remove beyond the Mississippi. A party of the Indians had proceeded to the territory appointed for their reception, and reported favorably upon their return. Everything promised a speedy conformity to the wishes of the government. But at this juncture, John Hext, the most influential chief of the tribe, died, and was succeeded in power, by Osceola. This chief wielded his power for far different purposes. Being opposed to emigration, he inflamed the minds of his people against the whites, and used every art to induce them to remain on their old hunting grounds. His conduct became so violent, that he was arrested by the Indian agent, and put in irons; but, promising to give up his opposition, he was set free.

On the 19th of July, 1835, some Indians who had met by appointment near Jogstown settlement, for the purpose of hunting, were attacked by a party of white men and flogged with cowhide whips. While this was going on, two other Indians arrived, who raised the war whoop and fired upon the whites. The firing was returned, one of the Indians killed, and the other wounded. Three of the whites were also wounded.

On the evening of August 6th, Dalton, the mail carrier from Tampa Bay to Camp King, was murdered by a party of Indians. General Thompson, the Indian agent, immediately convened the chiefs and demanded that the offenders should be delivered up to justice. The chiefs promised to comply. But did not, and it soon became evident, that a terrible storm was about to burst upon the settlements of Florida. The savages Seminoles retired into the wilds and forests, and, as much as possible, avoided all inter-course with the whites.

In September, Charles Amathla, a friendly chief of great influence, while journeying with his daughter, was shot by some Mickasukies, led by Osceola. Similar outrages increased in number. The interior settlements were abandoned; families deserted the fruits of many years’ labor, and fled to other states. General Clinch’s force numbered but one hundred and sixty men; and receiving no assistance from President Jackson, he obtained six hundred and fifty militia from the executive of Florida. With this reinforcement, he marched against the station on the Ouithlacooche River.

On the 23d of December, the companies of Captains Gardiner and Frazer, of the United States army, marched under the command of Major Dade, from Tampa Bay for Camp King. On the road, Dade wrote to Major Belton, urging him to forward a six-pounder, which had been left four miles behind, in consequence of the failure of the team which was to have been used in transporting it. Three horses were purchased with the necessary harness, and it joined the column that night. From this time no more was heard of the detachment until the 29th of December, when John Thomas, one of the soldiers, returned, and on the 31st, Rawson Clarke. The melancholy fate of his companions was related by the latter as follows:

“It was eight o’clock. Suddenly I heard a rifle shot in the direction of the advance guard, and this was immediately followed by a musket shot from that quarter. Captain Frazer had ridden by me a moment before, in that direction. I never saw him afterwards. I had not time to think of the meaning of these shots before a volley, as if from a thousand rifles, was poured in upon us from the front, and all along our left flank. I looked around me, and it seemed as if I was the only one left standing in the right wing. Neither could I, until several other volleys had been fired at us, see an enemy and when I did, I could only see their heads and arms peering out from the long grass, far and near, and from behind the pine trees. The ground seemed to me an open pine barren, entirely destitute of any hammock. On our right and a little to our rear was a large pond of water some distance off. All around us were heavy pine trees, very open, particularly towards the left, and abounding with long high grass. The first fire of the Indians was the most destructive, seemingly killing or disabling one-half of our men.

“We promptly threw ourselves behind trees, and opened a sharp fire of musketry. I for one never fired without seeing my man, that is, his head and shoulders. The Indians chiefly fired lying or squatting in the grass. Lieutenant Bassinger fired five or six pounds of canister from the cannon. This appeared to frighten the Indians, and they retreated over a little hill to our left, one-half or three-quarters of a mile off, after having fired not more than twelve or fifteen rounds. We immediately began to fell trees, and to erect a triangular breastwork. Some of us went forward to gather the cartridge boxes from the dead, and to assist the wounded. I had seen Major Bade fall to the ground by the first volley, and his horse dashed into the midst of the enemy. Whilst gathering the cartridges, I saw Lieutenant Mudge, sitting with his back reclining against a tree, and evidently dying. I spoke to him, but he did not answer. The interpreter, Louis, it is said, fell by the first fire.

“We had barely raised our breastwork knee high, when wo again saw the Indians advancing, in great numbers, over the hill to our left. They came on boldly till within long musket shot, when they spread themselves from tree to tree to surround us. We immediately extended as light infantry, covering ourselves by the trees, and opening a brisk fire from cannon and musketry. I do not think that the former could have done much mischief, the Indians were so scattered.

“Captain Gardiner, Lieutenant Bassinger, and Dr. Gatlen were the only officers left unhurt by the volley which killed Major Bade. Lieutenant Henderson had his left arm broken, but he continued to load and fire his musket, resting on the stump until he was finally shot down. Toward the close of the second attack, and during the day he kept up his spirits and cheered the men. Lieutenant Keyes had both his arms broken in the first attack; they were bound up and slung in a handkerchief, and he sat for the remainder of the day, until he was killed, reclining against the breastwork, his head often reposing upon it, regardless of everything that was passing around him.

“Our men were by degrees all cut down. We had maintained a steady fire from eight until two P. M., and allowing three-quarters of an hour interval between the first and second attack, had been pretty busily engaged for more than five hours. Lieutenant Bassinger was the only officer left alive, and he severely wounded. He told me, as the Indians approached, to lie down and feign myself dead. I looked through the logs and saw the savages approaching in great numbers. A heavy made Indian of middle stature, painted down to the waist, and whom I supposed to have been Micanope, seemed to be the chief. He made them a speech, frequently pointing to the breastwork. At length they charged into the work. There was none to offer resistance, and they did not seem to suspect the wounded being alive offering no indignity, but stepping about carefully, quietly stripping off our accoutrements, and carrying away our arms. They then retired in a body, in the direction from whence they came.

“Immediately after their retreat, forty or fifty Blacks and Indians on horseback, galloped up, alighted, and having tied their beasts, commenced, with horrid shouts and yells, the butchering of the wounded, together with an indiscriminate plunder, stripping the dead of clothing, watches, and money, and splitting open the heads of all who showed the least signs of life, with their axes and knives. This bloody work was accompanied with obscene and taunting derision, and oft repeated shouts.

“Lieutenant Bassinger, hearing the Blacks and Indians butchering the wounded, at length sprang up, and asked them to spare his life. They met him with the blows of their axes, and their fiendish laughter. Having been wounded in five different places myself, I was pretty well covered with blood; and two scratches that I had received on the head gave me the appearance of having been shot through the brain: for the Blacks, after catching me up by the heels, threw me down, exclaiming that I was dead enough. Then, stripping me of my clothes, shoes, and hat, they left me. After serving all the dead in this manner, they trundled off the cannon in the direction the Indians had gone, and went away. I saw them shoot down the oxen in their gear and burn the wagon.

“One of the other soldiers who escaped, says they threw the cannon in a pond, and burned its carriage also. Shortly after the Blacks went away, one Wilson, of Captain Gardiner’s company, crept from under some of the dead bodies, and seemed to be hardly hurt at all. He asked me to go with him back to the fort, and I was going to follow him, when, as he jumped over the breastwork, an Indian sprang from behind a tree and shot him down. I then lay quiet until nine o’clock that night, when D. Long, the only living soul beside myself, and I, started upon our journey. We knew it was nearest to go to Fort King, but we did not know the way, and had seen the enemy retreat in that direction. As I came out I saw Dr. Gatlen lying stripped amongst the dead. The last I saw of him whilst living, was kneeling behind the breastwork, with two double barrel guns by him, and he said, ‘Well, I have got four barrels for them!’ Captain Gardiner, after being severely wounded, cried out, ‘I can give you no more orders, my lads, do your best!’ I last saw a Negro spurn his body, saying, with an oath, ‘that’s one of their officers.’

“My comrade and myself got along quite well until the next day, when we met an Indian on horseback, armed with a rifle, coming up the road. Our only chance was to separate we did so. I took the right, and he the left of the road. The Indian pursued him. Shortly afterwards I heard a rifle shot, and a little after another. I concealed myself among some scrub, and saw palmetto, and after awhile saw the Indian pass looking for me. Suddenly, however, he put spurs to his horse, and went off at a gallop towards the road.

“I made something of a circuit before I struck the beaten track again. That night, I was a good deal annoyed by the wolves, who had scented my blood, and came very close to me. The next day, the 30th, I reached the fort.”

Thus perished one hundred and six men, under circumstances of hopelessness and misery, rarely equaled in modern warfare. Intelligence of this tragic event spread a degree of horror throughout the country, lasting and powerful; and even at the present day, the name of the gallant, ill fated Dade, is a spell word to conjure up feelings of sorrow. Three of the whole command escaped.

On the 6th of January, 1836, thirty Indians attacked the family of Mr. Cooly, on New River, while he was absent from home. They murdered Mrs. Cooly, three children, and Mr. Flinter, their teacher. During this transaction, the neighboring families made their escape into the more thickly settled territory. Cooly had long resided among the Indians, and always treated them kindly, and this renders the massacre more atrocious.

Previous to this, General Clinch fought a severe engagement with the Indians, near the Ouithlacooche River. He marched from Fort King, on the 29th of December, with a considerable force, and on the 31st, when half of the troops had crossed the river; the battalion of regulars were attacked by a large force of Indians, led by Osceola. The regulars met the attack of the vastly superior enemy with firmness. The action lasted nearly an hour, during which time the troops made three brilliant charges, driving the enemy in every direction. No inducement would prevail on the remainder of the army that had crossed the river, to return and assist their companions. After losing nearly one-third of their number, the regulars succeeded in crossing the river.

Meanwhile, the eastern settlements in the neighborhood of San Augustine were ravaged by the enemy, many of the inhabitants slain, and the Blacks carried away. So disastrous were these ravages, that in East Florida, five hundred families were driven from their homes, and their entire possessions destroyed by the Indians.

General Gaines, as commander of the southern division of the army, was actively engaged in raising a body of troops. He reached Fort King on the 22d of February, and thence moved down the Ouithlacooche. On the 27th, he had a slight skirmish with the enemy at General Clinch’s crossing place, where he lost one killed and eight wounded. Next day the army was attacked, Lieutenant Izard mortally wounded, one man killed, and two others wounded. Skirmishing was renewed on the 29th; one man killed and thirty-three wounded. This partisan warfare was continued until the 5th of March the United States troops losing several men in killed and wounded.

On the 5th, a number of Indians, headed by Osceola, appeared before General Gaines’s camp, and expressed their willingness to terminate hostilities. They were told that on condition of retiring south of the Ouithlacoochee, and attending a council when called on by the United States commissioners, they should not be molested. To this they agreed; but at this moment General Clinch, who had been summoned by express from Fort Drane, encountered their main body; and supposing themselves surrounded by deliberate stratagem, they fled with precipitation. This unfortunate accident put an end to negotiations for that time. Soon after, ascertaining that he had been superseded, General Gaines transferred the command to General Clinch, who retired with his whole force to Fort Drane.

General Scott now received the chief command in Florida, and commenced a new plan of operations, which, as is believed, would have speedily terminated the war; but unexpectedly he was superseded, and summoned to Washington on court-martial. His trial eventuated in full, honorable acquittal from all blame, but meanwhile he had been superseded by General Jessup. The measures of this officer were unimportant.

The summer and fall of 1837 passed away without any prospect of a reconciliation with the Indians; but in December, Colonel Zachary Taylor, who commanded a regiment of Jessup’s troops, came upon the trail of the Indians, and commenced a vigorous pursuit. On the 25th, at the head of about five hundred men, he came up with about seven hundred Indians, on the banks of the Okee-cho-bee Lake, under the celebrated chiefs, Alligator, Sam Jones, and Coacoochee. This battle was sought by both parties. On the day previous to the engagement, the colonel had received a challenge from Alligator, informing him of his position, and courting an attack. The Indians were posted in a thick swamp, covered in front by a small stream, whose quicksand rendered it almost impassable. Through this the Americans waded, sometimes sinking to the waist in mud and water, and totally unable to employ their horses. On reaching the borders of the hammock, the advance received a heavy fire, which killed their leader, (Colonel Gentry,) and drove them back in confusion. The main body then rushed into action, attacking the enemy under a galling fire, and fought from half past twelve until three P. M., although exposed to the full range of the enemy’s fire. With one exception, every officer in the sixth infantry was shot down, and one of the companies had but four members untouched. The Indians were forced from their position, and driven a considerable distance toward the extremity of Okee-cho-bee lake.

In consequence of his success in this battle, Colonel Taylor was enabled to advance further into the country than any previous commander had done. But the difficulty of transporting supplies, enabled the Seminoles to rest secure among their swamps and forests, and rendered the termination of the war impracticable. In April, 1838, Taylor was appointed to the chief command in Florida, with the rank of brevet brigadier-general. He skirmished with the enemy, but could never again force them to a general battle. Bloodhounds were employed to trace their hiding places, but were found to be of little use and abandoned.

A series of the most horrible outrages were committed about this time by the savages Seminoles. Settlers were shot down while sitting in the door of their own houses, and, sometimes, the houses were surrounded and burned while whole families were in them. On the 28th of July, 1839, a body of dragoons, under Lieutenant-colonel Harney, was sent to the Coloosahatchee, to establish a trading house, in conformity with Macomb’s treaty. The Indians had manifested a friendly disposition for some time, daily visiting the camp and trading. So completely had they lulled the troops into security that no defense was erected and no guard maintained. The camp was on the margin of the river. At dawn, on the 23d of July, the savages Seminoles made a simultaneous attack upon the camp and the trading house. Those who escaped the first discharge fled naked to the river, and escaped in some fishing smacks. Colonel Harney was among them. While descending the river, the sergeant and four others were called to the shore by a well known Indian, and assured that they would not be harmed. They complied, and were butchered. Altogether eighteen were killed. Colonel Harney afterwards cautiously approached the spot, and found eleven bodies shockingly mutilated, and two hundred and fifty Indians in the neighborhood, dancing and whooping with triumph.

In 1840, the Indians accomplished an expedition which was creditable to their enterprise, but was attended with all the circumstances of horror usual in Indian warfare. Indian Key, an island of about seven acres in extent, about thirty miles from the southern Atlantic coast of Florida, was invested by seventeen boats, containing Indians, headed by Chekekia. Seven of the inhabitants Mr. Motte, Mrs. Motte, Dr. Perrine, three children and a slave, were murdered, the island plundered and the buildings burned. The rest of the inhabitants escaped in boats to a schooner. This was one of the boldest conceived, and most successfully executed, enterprises of the war.

In 1840, General Taylor requested permission to retire from Florida, which was granted, and in April, General Armistead was appointed to succeed him. The operations of this officer were, necessarily of the same tedious and unsatisfactory character as most of his predecessors had been, and in May, 1841, he was succeeded by Colonel Worth.

This officer commenced the campaign under very unfavorable circumstances, having no less than twelve hundred men sick and unfit for duty. On assuming command he is said to have named the 1st of January, 1842, as the time when he hoped to bring the war to a close.

In August, the famous chief, Wild Cat, surrendered his whole band, including Coacoochee and his family, at Tampa. On the 13th the example was followed by a considerable number of Hospitaki’s party, and next month by many of the Tallahassee tribe. Subsequently, various chiefs and their bands were regularly brought in.

Nothing, however, of a decisive nature took place until the 19th of April, 1842, when Colonel Worth found the enemy in considerable force, strongly fortified, near Okeehuinpbee swamp. An immediate attack was made and the Indians totally defeated.

Every trail made in their flight was taken and pursued until dark, and renewed on the following morning, the detachments marching each day, some twenty and some thirty miles. The scene of this battle was the big hammock of Palaklaklaha. As a reward for his services in this affair, Worth was brevetted by government, brigadier-general. Soon after, (May 4th,) Hallush-Tustemuggee, with eighty of his band, came to Palatka and sub-mitted, and on the 12th of August, Colonel Worth announced in general orders, that the Florida war was ended. This assertion, however, was premature, for hostilities again recommenced, and Worth received the surrender of a large body of Creeks at Tampa.

Battle of Palaklaklaha

The battle of Palaklaklaha was the last important incident of the Florida war. Its close was thus announced by President Tyler, in his message of December 8th, 1842.

“The vexatious, harassing, and expensive war which so long prevailed with the Indian tribes inhabiting the peninsula of Florida has happily been terminated: whereby our army has been relieved from a service of the most disagreeable character, and the treasury from a large expenditure. Some casual outbreaks may occur, such as are incident to the close proximity of border settlements and the Indians; but these, as in all other cases, may be left to the care of the local authorities, aided, when occasion may require, by the forces of the United States. A sufficient number of troops will be maintained in Florida, so long as the remotest apprehension of danger shall exist; yet their duties will be limited rather to the garrisoning of the necessary posts than to the maintenance of active hostilities. It is to be hoped that a territory so long retarded in its growth, will now speedily recover from the evils incident to a protracted war, exhibiting in the increased amount of its rich productions, true evidences of returning wealth and prosperity. By the practice of rigid justice towards the numerous Indian tribes, residing within our territorial limits, and the exercise of parental vigilance over their interests, protecting them against fraud and intrusion, and at the same time using every proper expedient to introduce among them the arts of civilized life, we may fondly hope, not only to wean them from the love of war, but to inspire them with a love of peace and all its avocations. With several of the tribes, great progress in civilizing them has already been made. The school-master and the missionary are found side by side, and the remains of what were once numerous and powerful nations may yet be preserved as the builders up of a new name for themselves and their posterity.”

The Seminole war, thus happily terminated, had been the least glorious in which the United States had ever engaged. Occasionally, a signal triumph was obtained by the most untiring exertion, but the consequences were scarcely felt by the rapid and swamp covered enemy. Great numbers of men had been worn out by a service requiring so much exertion; able generals baffled, and millions of dollars expended without apparent effect. The territory had been rendered almost uninhabitable, and the name of it is forever associated with deeds of terror and horrible sufferings. It is most probable, that the struggle was hastened by the lawless conduct of a few whites. Most of the Florida Indians were eventually transported to the Indian Territory, though some managed to stay behind in the swamp lands.