Governor Stevens soon learned that, as an adjunct to the Yakima War, there had been serious outbreaks in the Puget Sound country and that there was every prospect of more to follow soon.

Often designated as “The Battles of Puget Sound” or “The Battle of Seattle” they were really a part of the Yakima War and are detailed here not alone for their intrinsic historical interest but also to show the wide-spread disaffection of the Western Washington tribes. Kamiakin, principal chief of the Yakima, was adept in his use of emissaries to incite and to threaten reprisals on any tribe which did not co-operate with him.

The Indians, who lived on several of the Puget Sound Rivers, namely, the Snoqualmie, Nisqually, Puyallup, Cowlitz, Cedar, Green, and White rivers, were all related to the Yakima and the Klickitat. Chief Leschi of the Nisqually tribe was half Yakima and a willing lieutenant of Kamiakin. In the summer of 1855 much information reached the authorities in Washington Territory to the effect that an Indian war was imminent. The news was conveyed by friendly chiefs and by the Indian wives of white men. Some treaties had been made by Governor Stevens, others were contemplated or in process, but seldom was any tribe unanimously for peace. Usually a part of each tribe favored war. The situation in the Puget Sound Basin was no different in that respect than the rest of the Territory.

On September 27, 1855, the home of A. L. Porter on the White River was attacked. Porter had anticipated such an event and had hidden in the underbrush, escaping capture. Next morning he spread the alarm and the settlers from that district all hastened into Seattle. In the absence of Governor Stevens, Acting Governor Charles H. Mason requested soldiers from Fort Steilacoom.

A detachment under Lieutenant Nugent was sent and the soldiers marched through the district where they were met .with nothing but assurances of friendliness on the part of the Indians. Returning to Seattle, Nugent, with Mason’s assistance, advised the settlers that there was no cause for alarm and that they should return to their homes, which advice most of them followed. On October 28th those who had returned were massacred. Three children were saved by a friendly Indian known as Old Tom, who placed the children under a bearskin in his canoe and paddled down to Seattle. Chief Kitsap, the elder, for whom Kitsap County, Washington, is named, warned the whites living in the Puyallup Valley, and they escaped at night while the Indians were waiting for daylight to kill them.

Acting Governor Mason asked the Hudson’s Bay Company for arms and ammunition. Immediately fifty guns and a large supply of ammunition were sent. This act puzzled the Indians who thought that the British would help in the extermination of the Americans.

Captain C. C. Hewitt, with his company of volunteers, went to the White River Valley to bury the dead and to rescue any who might have escaped by hiding. None was found to rescue. In November this company was again ordered into the White River Valley to cooperate with troops being sent from Fort Steilacoom under Lieutenant W. A. Slaughter. On November 25 Slaughter’s force was attacked during a dense fog by Klickitat, Nisquallie, and Green River Indians. One soldier was killed and forty horses belonging to the troopers were stolen. On December 4th Lieutenant Slaughter and Captain Hewitt were conferring at a cabin near, the junction of the White and Green rivers, when Lieutenant Slaughter was shot and instantly killed by a lurking Indian. Later a town was to be located at that site and named “Slaughter,” but the name was subsequently changed to its present designation, “Auburn.”

The sloop-of-war Decatur was in Seattle harbor when Governor Isaac I. Stevens returned to Olympia on January 19, 1856. Friendly Indians gave warning of the approach of hostiles by way of Lake Washington on January 25th. The men from the Decatur remained ashore on guard that night and returned to the sloop next morning for a breakfast they were destined not to eat. An alarm sounded and the men went ashore, taking a howitzer with them. They sent a shot where the Indians were supposed to be hiding and immediately received a volley of rifle fire. That circumstance initiated the Battle of Seattle which raged until ten o’clock that night. Two white men were killed and, as usual, the Indians concealed their losses. The hostiles were defeated but sent word that they would return with a force sufficient to take Seattle even with the support of a battleship. A strong stockade was built and Governor Stevens kept the volunteers constantly scouring the country. Captain Maloney was in the White River Valley with 125 men and in February Lieutenant-Colonel Casey came up from Fort Steilacoom with two companies and joined with Maloney’s force. Two companies of volunteers also headed in the same direction, established depots at two points and built a blockhouse and constructed a ferry at the Puyallup River crossing. Meanwhile depredations broke out anew south of Fort Steilacoom. On March 4 Lieutenant Kautz, with a detachment of regulars, was busy opening a road from the Puyallup River to Muckilshoot Prairie when they were attacked by a large force of Indians. One soldier was killed and nine, including Lieutenant Kautz, were wounded.

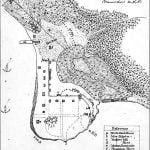

Map of Seattle

A map of Seattle, drawn at the time of the Battle of Seattle, part of the Puget Sound War. Map shows the sloop USS Decatur and the bark Brontes in Elliott Bay, Henry Yesler’s mill, wharf, and a pile of sawdust, indigenous settlements in and around town (depicted with tipi-like symbols). The camp in town is labeled “Tecumseh’s Camp”, the one in the woods just north of Yesler’s Mill is labeled “Curley’s Camp” On the slopes above the town there is text saying “Hills and Woods thronged with Indians”. A sand spit separates a tide marsh from the tide flats of the bay. The location is roughly where Seattle’s Pioneer Square is today. The main north-south street is today’s First Avenue, the main west-east street shown is today’s Jackson Street. Today’s Yesler Way would terminate at the wharf. The marsh and tide flats have been filled and developed since 1855.

The Battle of Connell’s Prairie occurred on March 8th. Two small companies of volunteers had been sent to the White River crossing to establish a ferry and build a blockhouse. They were vigorously attacked by 150 Indians. The volunteers charged, put-ting the Indians to flight. The total casualties for the volunteers were four wounded while the Indians lost thirty killed and many wounded. That result encouraged the white men and discouraged the hostiles. It was the last battle west of the Cascades in which the Indians appeared in force in the Puget Sound area. Subsequent attacks were confined to surprise raids by small bands.

The U. S. S. Massachusetts arrived in Seattle harbor on February 24, 1856. A month later the U. S. S. John Hancock put in its appearance, which arrivals did much to convince the Indians thereabout that they were on the losing side. However, hostiles came down from the north and upon refusing to return whence they came, were attacked by men from the ships. Twenty-seven Indians were killed and twenty-one wounded out of a total of 117 warriors. Their canoes and supplies were destroyed and the survivors surrendered. They were transported to Victoria Island aboard the Massachusetts and the episode took all idea of fight out of the Northern Indians.

As an additional safeguard two new forts were built, Fort Townsend across the strait from Victoria, and Fort Bellingham, on the mainland east of the San Juan Islands. The ringleaders among the hostile chiefs were hunted down and executed. The volunteers of Washington Territory had proved their mettle. They had built 35 stockades, blockhouses and forts; other citizens had built 23 more; and the regular troops, seven. Roads and trails had been finished and the entire cost was defrayed by the auction of animals captured from the Indians.

Through the fine efforts of Governor Stevens attention of the nation was focused on the Territory and it was on its way to eventually take its place in the roster of states.