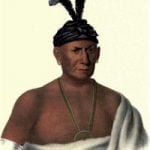

or The Crouching Eagle

Wakechai, or the Crouching Eagle, was one of the village chiefs, or civil magistrates, of the Saukie nation, and resided at the principal town of that people, near the confluence of Rock river with the Mississippi, in one of the most beautiful regions of Illinois. This neighborhood has been abandoned by its Indian inhabitants, who have recently removed to the Iowa territory, on the opposite shore of the Mississippi; but it will always be considered as classic ground, by those who shall be engaged in researches into the history of the Aborigines, as well on account of the unrivaled beauty of the scenery, as from the many interesting recollections connected with the soil.

The subject of this notice was a person of low stature, with a stooping and ungraceful form, a shuffling gait, a stern savage expression of countenance, and a deportment altogether displeasing and undignified. Though named after the noble bird, regarded by the Indians as the most warlike of the feathered tribes, and whose plumage is appropriated to the decoration of the warrior’s brow, this chief never acquired any reputation as a brave, nor do we know that he ever performed any warlike feat worthy to be mentioned. That he has been upon the war-path, is most probable, for among a people so entirely military, some service is expected of every individual. But it is certain, that the Crouching Eagle, or as we should interpret the- name, the Eagle stooping upon his prey, gained no laurels in the field, and never rose to be a leader in any expedition. Neither did he excel in manly sports, or in the ceremonious dances, so highly esteemed in savage life.

It may be very naturally inquired, by what means a person destitute of the qualities which are held in the highest repute among his people, became a chief and a person of influence among them Without the physical powers which are so greatly valued in savage life, with no reputation for valor, nor any trophy snatched from the enemy by force or cunning, it would not seem that there was any community of feeling between him and his associates, through which he could conciliate their kindness, or command respect.

The answer to the inquiries which we have suggested, shows the vast superiority of mind over any and all endowments that are merely physical. Even in the savage state, under all the disadvantages which surround it, prevent its culture, and cramp its exercise, the intellect silently asserts its supremacy, and the warrior, while he affects to despise it, unconsciously yields to its sway. The Eagle was a man of vigorous and clear mind, whose judicious counsels were of more advantage to his tribe, than any services he could have rendered in the field, even supposing his prowess to have been equal to his sagacity. If nature denied him the swift foot, and the strong arm of the warrior, it endowed him with a prompt and bold heart, and a cool judgment to direct the energies of others. He was not an orator, to win the admiration of multitudes, nor had he those popular and insinuating talents and manners, which often raise individuals of little solid worth to high station and extensive influence. He was a calm and sage man. His nation had confidence in his wisdom; he was considered a prudent and safe counselor. He gave his attention to public business, became skilled in the affairs of his people, and acquired a character for fidelity, which raised him to places of trust. Perhaps the braves and war-chiefs, the hot-blooded, turbulent, and ambitious aspirants for place and honor, submitted the more readily to the counsels of one who was not a rival, and cheerfully yielded him precedence in a sphere in which they were not competitors.

It is recorded of Tecumthe and of Red Jacket, that each of them in his first engagement with the enemy showed discreditable symptoms of fear; the former became afterwards the most distinguished Indian leader of his time, and both of them enjoyed deservedly the most unlimited influence over their respective nations. These facts are interesting from the evidence they afford of the supremacy of the intellectual over the physical man, in savage as well as in civilized life.

The man of peace, however valuable his services, seldom occupies a brilliant page in history; and Wakechai, though a diligent and useful public man, has left but little trace of his career. The only striking incident which has been preserved in relation to him, is connected with his last moments. He had been lying ill some days, and was laboring under the delirium of a fever, when he dreamed, or imagined, that a supernatural revelation directed him to throw himself into the water, at a spot where Rock river unites with the Mississippi, where his good Manito, or guardian spirit, would meet him, and instantly restore him to health. The savage who knows no God, and

“Whose soul proud science never taught to stray,

Far as the solar walk, or milky way,

is easily deluded by the most absurd superstitions. Every human spirit looks up to something greater than itself; and when the helplessness induced by disease or misfortune, brings an humbling sense of self-abasement, the savage, as well as the saint and the sage, grasps at that which to each, though in a far different sense, is a religion the belief in a superior intelligence. The blind credulity of the Indian in this respect, is a singular feature in his character, and exhibits a remarkable contrast between the religion of the savage and that of the Christian. In his intercourse with men, whether friends or enemies, the savage is suspicious, cautious, and slow in giving his confidence; while in regard to the invisible world, he yields credence to the visions of his own imagination, and the idlest fables of the ignorant or designing, not only without evidence, but against the plain experience of his own senses. In the instance before us, a man of more than ordinary common sense, a sagacious counselor, accustomed to the examination of facts, and to reasoning upon questions of difficulty, suffered himself to be deceived into the belief that he could plunge with impunity into the water, while enfeebled by disease, and that in the bosom of that element he should meet and converse with a supernatural being, such as he had not only never seen, but of which he could have heard no distinct, rational, or credible account. We cannot avoid the persuasion, that such a fact, while it evinces the imbecility of the human intellect, in reference to the contemplation of the hidden things of another life, does also strongly indicate an innate belief working in the natural mind, and a want, which nothing but a revelation can rightly direct, or fully satisfy.

Wakechai believed and obeyed the vision, nor did any venture to interpose an objection to the performance of that which seemed a religious duty. He arose, and with much difficulty proceeded to the margin of the river. He paused for a moment at that romantic spot, which presents one of the loveliest landscapes ever offered to the human eye. Perhaps he paused to contemplate the great river, which, rising in far distant lakes on the one hand, and rolling away to the ocean on the other, and washing far distant, and to him unknown, lands in its course, may have figured to him his own existence, the beginning and the end of which were equally beyond his comprehension. The fatal plunge was made, with undaunted courage, and doubtless with unaltered faith, and the deluded man awoke to the consciousness that he was deceived. The clear stream received and enclosed him in its cold embrace, but no mysterious form met his eye, nor did any friendly voice impart the desired secret. The limbs that should have been renovated, scarcely retained sufficient strength to enable the deluded sufferer to rise again into his native element; he regained the shore with difficulty, where he sunk exhausted, and being carried back to his lodge, died in the evening of the same day.

Wakechai was a popular and respected chief, and was a great favorite of the whites, who found him uniformly friendly, honest, and disposed to maintain peace between his own nation and the American people. He was a person of steady mind, and may be regarded as one of the few statesmen of this little republic who watched and reflected over its interests, and directed its affairs, while others fought its battles. His death was greatly regretted by his own people, and by the American residents of Rock Island.

He was one of the delegation who accompanied General Clarke to Washington, in 1824, when his portrait was taken.