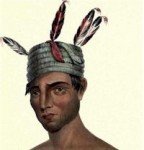

Wakaun Haka is of mixed blood; his father was a Frenchman, and his mother a woman of the Winnebago nation. He is one of the finest looking men among that people, and has for many years been one of their principal speakers on all public occasions. The’ qualifications for this office are not very extensive, and in general comprise little else than fluency, a graceful manner, and a familiar acquaintance with the current transactions of the day. Wakaun Haka, or the Snake-Skin, possesses these qualities in a high degree; his stature is about six feet three inches, his person erect and commanding, and his delivery easy. He is between fifty and sixty years of age, and is one of the war-chiefs of the Winnebago.

In the early years of the Snake-Skin, he was a successful hunter, a warrior of fair standing, and a person of decided influence among his people. But the sin that most easily besets the Indian has destroyed his usefulness; habits of dissipation, with the premature decrepitude incident to the savage life, have made him an old man, at the age at which the statesmen of civilized nations are in the enjoyment of the highest degree of intellectual vigor. His influence has declined, and many of his band have left him, and joined the standards of other chiefs.

This personage has been the husband of no less than eleven wives, and the father of a numerous progeny. With all the savage love of trinkets and finery, he had his full share of the personal vanity which nourishes that reigning propensity, and of which the following anecdote affords a striking illustration. In one of the drunken broils, which have not been infrequent in the latter part of his life, a fight occurred between himself arid another person, in which the nose of the chief was severely bitten. The Reverend Mr. Lowry, superintendent of the school, on hearing of the accident, paid the chief a visit of condolence, hoping that an opportunity might offer, which might enable him to give salutary advice to the sufferer. He was lying with his head covered, refusing to be seen. His wife, deeply affected by the misfortune, and terrified by the excited state of her husband’s mind, sat near him, weeping bitterly. When she announced the name of his visitor, the chief, still concealing his mutilated features, exclaimed that he was a ruined man, and desired only to die. He continued to bewail his misfortune as one which it would be unworthy in a man and a warrior to survive, and as altogether intolerable. His only consolation was found in the declaration that his young men should kill the author of his disgrace; and accordingly the latter was soon after murdered, though it is not known by whom. Had not this injury been of a kind by which the vanity of Wakaun Haka was affected, and his self-love mortified, it might have been forgotten or passed over; we do not say forgiven, as this word, in our acceptance of it, expresses an idea to which the savage is a stranger. Regarding an un-revenged insult as a trader views an outstanding debt, which he may demand whenever he can find the delinquent party in a condition to pay it, he is satisfied by a suitable compensation, if the injury be of a character to admit of compromise. Had his wife, for instance, eloped with a lover, or his brother been slain, the offender might have purchased peace at the expense of a few horses; but what price could indemnify a great chief for the loss of his nose ? Happily, the wound proved but slight, and Wakaun Haka lost neither his nose nor his reputation.

We do not intend, however, by the last remark, to do injustice to this chief, who, on another occasion, nursed his resentment, under the influence of highly creditable feelings. We have had occasion to mention elsewhere, a striking incident of border warfare, which occurred in 1834, when a war-party of Saukies and Foxes surprised a small encampment of the Winnebago, and massacred all the persons within it, except one gallant boy, about twelve years of age, who, after discharging a gun, and killing a Saukie brave, made his escape by swimming the Mississippi, and brought the news of the slaughter to Fort Crawford, at Prairie du Chien. That boy was the son of Wakaun Haka, and among the slain was one of the wives and several of the children of this chief. The exploit was considered as conferring great honor on the lad, as well as upon his family, and the father evinced the pride which he felt in his son, while he lamented over the slain members of his family with a lively sensibility. An exterminating war was expected to follow this bloody deed; but by the prompt interposition of the agent of the United States, and the military officers, a treaty was held, and a peace brought about, chiefly through the politic and conciliatory conduct of Keokuk, the head man of the offending nation. Forty horses were presented to the Winnebago, as a full compensation for the loss of about half that number of their people, who had been massacred in cold blood; the indemnity was accepted, the peace pipe was smoked, and the hands of the murderers, cleansed of the foul stains of midnight assassination, were clasped in the embrace of amity by the relatives of the slain. Wakaun Haka, with a disdain for so unworthy a compromise, which did honor to his feelings as a husband and father, stood aloof, and refused either to participate in the present, or to give his hand to the Saukies and Foxes.

The Snake-Skin, like many other influential men among the Indians, has always been obstinately opposed to all changes in the condition of his people, and has declined taking any part in the benevolent plans of the American Government, or of individuals, for the civilization of his race. On one occasion, when the superintendent of the school called his attention to the subject, and urged the advantages which the Winnebago might derive from those benevolent measures, his reply was, that “the Great Spirit had made the skin of the Indian red, and that soap and water could not make it white. “At another time, when urged to use his influence to procure the attendance of the Indian youth at the government school, he replied that “their children were all asleep, and could not be waked up.” These answers were figurative, and contain the substance of the objection invariably urged by the savages on this subject: “The Great Spirit has made us what we are it is not his will that we should be changed; if it was his will, he would let us know; if it is not his will, it would be wrong for us to attempt it, nor could we by any art change our nature.”