Early in the eighteenth century the French had commenced extending their influence among the tribes who inhabited the country bordering on the great western lakes. Always more successful than the other European settlers in conciliating the affections of the savages among whom they lived, they had obtained the hearty good will of nations little known to the English. The cordial familiarity of the race, and the terms of easy equality upon which they were content to share the rude huts of the Indians, ingratiated them more readily with their hosts, than a course of English reserve and formality could have done. The most marked instances of the contrast between the two great parties of colonists may be seen in the different measure of success met with in their respective religious operations. While the stern doctrines of New England divines, as a general rule, were neglected or contemned by their rude hearers, the Jesuits met with signal success in acquiring a spiritual influence over the aborigines. Whether it was owing to the more attractive form in which they promulgated their creed and worship, or whether it was due to their personal readiness to adapt themselves to the habits, and to sympathize with the feelings of their proselytes, certain it is that they maintained a strong hold upon the affections, and a powerful influence over the conduct of their adopted brethren.

Adair, writing with natural prejudice, says that, “instead of reforming the Indians, the monks and friars corrupted their morals: for in the place of inculcating love, peace, and good-will to their red pupils, as became messengers of the divine, author of peace, they only impressed their flexible minds with an implacable hatred against every British subject, without any distinction. Our people will soon discover the bad policy of the late Quebec act, and it is to be hoped that Great Britain will, in due time, send those black croaking clerical frogs of Canada home to their infallible Mufti of Rome.” The Ottawa, Chippewa, and Pottawatomie, who dwelt on the Great Lakes, proved as stanch adherents to the French interests as were the Six Nations to those of the English, and the bitterest hostility prevailed between these two great divisions of the aboriginal population.

When English troops, in accordance with the treaty of 1760, were put in possession of the French stations on the lakes, they found the Indians little disposed to assent to the change. The great sachem who stood at the head of the confederate western tribes was the celebrated Ottawa chief Pontiac.

British Occupation Of The Western Posts

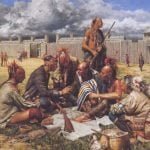

The first detachment, under Major Rogers, which entered the western country on the way to Detroit, the most important post on the lakes, was favorably received by the Indian chief, but not without a proud assertion of his own rights and authority. He sent a formal embassy to meet the English, and to announce his intention of giving an audience to their commander. Rogers describes him as a chief of noble appearance and dignified address. At the conference he inquired by what right the English entered his country; and upon the major s disavowing all hostile intent towards the Indians, seemed more placable, but checked any further advance, until his pleasure should be made known, with the pithy observation: ” I stand in the path you travel until to-morrow morning.” He finally allowed the forces to proceed, and even furnished men to protect them and their stores.

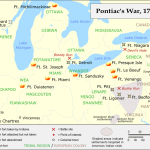

Pontiac assisted and protected this garrison for a period, but probably even then was pondering in his mind the great scheme of restoring his French allies and exterminating the intruders. He has been frequently compared to Philip, the great Wampanoag sachem, both for his kingly spirit and for the similarity of their plans to crush the encroachments of the English. Pontiac had an immense force under his control, and could well afford to distribute it in as many different detachments as there were strongholds of the enemy to be overthrown. It was in the year 1763 that his arrangements were completed, and the month of June was fixed upon for a simultaneous onslaught upon every British post. The eloquent and sagacious Ottowa chief had drawn into his conspiracy, not only the people of his own nation, with the Chippewa and Pottawatomie, but large numbers from other western tribes, as the Miami, the Sacs and Foxes, the Huron and the Shawanees. He even secured the alliance of a portion of the Delawares and of the Six Nations.

In vain were the officers of the garrisons at Michilimackinac and other distant forts warned by traders, who had ventured among the Indians, that a general disaffection was observable. They felt secure, and no special means were taken to avert the coming storm.

So well concerted were the arrangements for attack, and such consummate duplicity and deception were used in carrying them out, that nearly all the English forts at the west were, within a few days from the first demonstration, in the hands of the savages, the garrisons having been massacred or enslaved. No less than nine trading and military posts were destroyed. Of the seizure of Michilimackinac, next to Detroit the most important station on the lakes, we have the most particular account.

Hundreds of Indians, mostly Chippewa and Sac, had been loitering about the place for some days previous, and on the 4th of June they proceeded to celebrate the king s birthday by a great game at ball. This sport, carried on, as usual, with noise and tumult, threw the garrison off their guard, at the same time that it afforded a pretext for clambering into the fort. The ball was several times, as if by accident, knocked within the pickets, the whole gang rushing in pursuit of it with shouts. At a favorable moment they fell upon the English, dispersed and unsuspicious of intended harm, and before any effectual resistance could be made, murdered and scalped seventy of the number. The remainder, being twenty men, were taken captive. A Mr. Henry, who, by the good offices of a Pawnee woman, was concealed in the house of a Frenchman, gives a minute detail of the terrible scene. From his account, all the fury of the savage seems to have been aroused in the bosoms of the assailants. He avers that he saw them drinking the blood of their mangled victims in a transport of exulting rage.

Over an immense district of country, from the Ohio to the lakes, the outbreak of the combined nations spread desolation and dismay.